Kirstenbosch Hothouse

Beez Neez now Chy Whella

Big Bear and Pepe Millard

Mon 13 Jan 2020 23:57

|

Kirstenbosch Hothouse  Bimbling into the huge Hothouse at Kirstenbosch was a joy of new ‘stuff’ to us,

mostly from Namibia.

We turned right, found ourselves in a

‘little outside bit’ and took in some lovely

plants.....

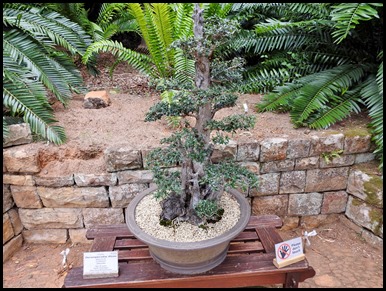

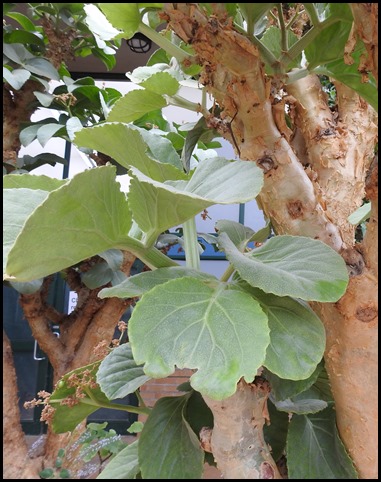

Another collection of Bonsai Trees.

My personal favourite Acer, although I do love the ones with dark purple, deeply

cut leaves best of all. This one is Chinese or Trident Maple (Acer buergerianum) and he is 70 years old.

A False

Olive (Buddleja saligna) aged 50 years and a Wild Olive (Olea europaea subsp. africana) aged 95

years.

Loved the holes and hollows in this

chaps trunk. He is a Chinese or Laccbark Elm

(Ulmus parvifolia) aged 25 years.

A fine Swamp or

Bald Cypress (Taxodium distichum) aged 25 years. Bear was busy reading an

interesting story.

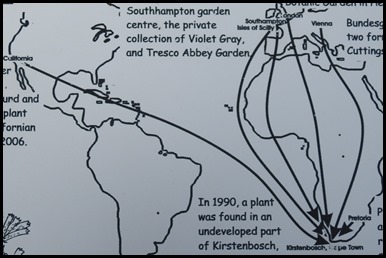

Saved from extinction: Erica verticillata once grew in the area between Rondebosch

and Rondeviei. Cuttings and seeds had been collected and plants cultivated at

Kirstenbosch and in other botanic gardens, but by the 1960s all the Kirstenbosch

Erica verticillata plants had died. When staff went to collect fresh seed and

cuttings from the wild plants, they searched all over what was left of its

habitat, but no plants were found. Erica verticillata was thought to be extinct.

Luckily plants had survived in other gardens and to date Kirstenbosch staff have

tracked down eight different individual plants. Today, this species survives in

cultivation at Kirstenbosch, and in many other botanic and private gardens all

over the world, and plants have been successfully re-introduced to reserves on

the Cape Flats.

The last recorded collection of a

wild plant was in 1908.

In 1990, a plant was found in an

underdeveloped part of Kirstenbosch, where ericas had been planted in the 1920

and ‘30s.

The Heather Society of Britain

found and returned three plants: from a Southampton garden centre, the private

collection of Violet Gray, and Tresco Abbey Garden (one of our favourite

places).

The Royal Botanic Garden, Kew

sent one in 1984 that proved to be a hybrid, and another in 2006 that was

originally sent to Kew from Fernkloof Botanic Garden in Hermanus.

Protea Park, Pretoria: a plant

growing here was recognised from herbarium sheets. Cuttings were sent to

Kirstenbosch in 1984.

Bundersgarten (Belvedere Palace)

in Vienna has been growing two forms since the 1790s, one true species, one

hybrid. Cuttings were returned to South Africa in 2001.

The Heather Society of America

found and returned a plant from a Californian nursery in 2006.

From these eight Erica

verticillata plants, thousands more have been grown from cuttings. We were too

late to prevent this species from dying out in nature, but we can make sure that

it survives by growing it in our gardens and looking after the seeds. What

a lovely story and so many societies and gardeners across

the world got involved to make this a success for the

future.

In the far corner we were drawn to

look at what at first glance looked like bits of tree stumps. We touched as the

information board suggested and found them cold to the touch and very stone-like

indeed. Trees of Stone: These are fossil tree

stumps. They were living trees about 240 million years ago, when South Africa

was part of the ancient continent of Gondwana. Today fossils like these are

found in the eastern Free State in the Senekal and Harrismith districts. When

living they were trees that looked similar to the Monkey Puzzle and Norfolk

Island Pine (Araucaria spp.) found in the South Pacific, Australia and

New Zealand today. There are no more of their kind native to Africa alive today.

This ancient plant group went extinct in Africa but survived in other parts of

Gondwana.

Fossil wood can tell us about the

climate long ago. The annual growth rings of these fossil trees indicate that

the climate was strongly seasonal, but wet and warm enough for forests to

grow.

How do trees turn to stone?: A

tree trunk may be swept away by a flood and then become covered in mud or sand.

This cuts out air (oxygen), which stops the normal process of decay by fungii

and bacteria. Gradually the sand layers build up and minerals enter the tree

trunk, slowly replacing the organic material, particle by particle. In this way

over a long time the organic wood becomes turned into mineral stone (petrified).

I think I need a rub down with the Evening Post....

Back inside the hothouse we went

anti-clockwise and chose some favourites from the first

collection.

Orchidaceae

(Eulophia ensata), and two Amaryllidaceae (Haemanthus humilis).

Lovely Flame

Lilies.

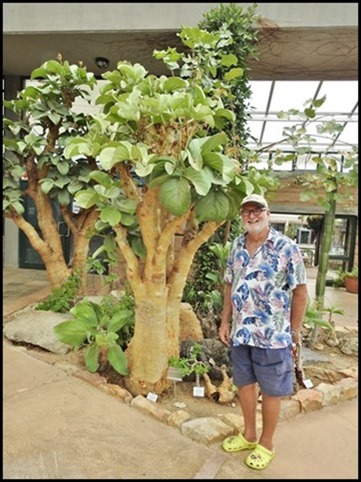

At the end of the path was a stout fellow called Cobas from the Namib (Cyphostemma

curroii).

Then we saw, in the far corner what

looked like ‘past it’s sell by date’ only to discover the most amazing plant we

have ever seen. Welwitschia mirabilis is a very

unusual plant from the Namib Desert. There is no other plant like it. It is made

up of just two leaves, a stem base and roots. It does not fit neatly into any

plant group because it bears cones like a cone-bearing plant (gynosperm), yet

has some characteristics of flowering-plants (angiosperms), and has no close

relatives. It is found growing wild only in the Namib, from Swakopmund in

northern Namibia in south-west Angola. Welwitschias produce only two strap-shaped leaves that keep

growing throughout the plant’s life, and are never shed. They become torn,

shredded and tattered with age. Some plants are estimated to be between 500 and

2000 years old.

Cones

are produced on both male and female plants (dioecious), both produce cones,

but, unlike other cone-bearing plants, Welwitschia cones contain modified flower-like structures that

are more like those found in flowering plants. The ‘flowers’ produce nectar,

which attracts small insects like flies and wasps, which pollinate them.

The stem of

a mature Welwitschia mirabilis is low,

sturdy, woody and hollowed out, like an ice-cream cone. They have this strange

shape because of their unique growth habit. The growing point at the tip of

their stems stops growing when they are still young. The stem margin continues

to grow out sideways, with no upward growth from the centre. Most of them grow

about half a metre tall, although the largest wild plant is nearly 3 m high and

about 9 m wide.

Welwitschia live in an extreme desert environment, yet has few adaptations to desert life that most desert plants have. In many ways this strange plant is more like the kind of plant you would expect to find in a moist tropical climate rather than a desert. Welwitschia does not store water in its stems or leaves. Desert plants have no leaves, small leaves or fleshy leaves, but Welwitschia has large, broad leaves. .

Welwitschia has many stomata in its leaves, more than most desert plants

do, and they are found on the upper and lower surfaces. Stomata are pores in the

leaf surface for gas exchange, and moisture is lost during this process – the

more stomata, the more water is lost. It was thought that Welwitschia could absorb fog and water vapour through the

stomata, but recent studies show that it cannot. Why it has so many stomata is a

puzzle.

Welwitschia has a very long taproot, which can reach

underground water. The broad leaves reflect much of the sun’s heat and light so

that the leaves don’t overheat. The leaves also shade the soil around the stem,

keeping the rots cooler and conserving any moisture in the

soil.

To grow Welwitschia we have brought the desert to Kirstenbosch. This bed

is filled with well-drained, desert sand, and heating cables keep it warm all

year round. The bed is deep to allow Welwitschia’s long tap root to develop. We sowed the seeds

directly in the bed, because the long tap root makes them difficult to

transplant. We treated the seedlings with a fungal inoculant and water once a

week in summer and once every three weeks in

winter.

The oldest Welwitschia in this house were sown in November

2010. Although some produced their first cones when they were only 13 months

old, it takes many years for them to develop their strange, woody,

hollowed-out-cone-like stems. After reading the information boards we

believe this is the most incredible plant we have ever

met....

In

the far corner we saw the most marvellous, showy

cactus – Apocynaceae (Hoodia gordonii).

Upstairs we saw far too many plants to name......

......but a little

chap in the corner had the reddest flowers, perhaps

ever.

The chap in the middle is Vitaceae (Cyphostemma bainesii) and the little

stumpy chaps are Asteraceae (Kleinia

stapliiformis).

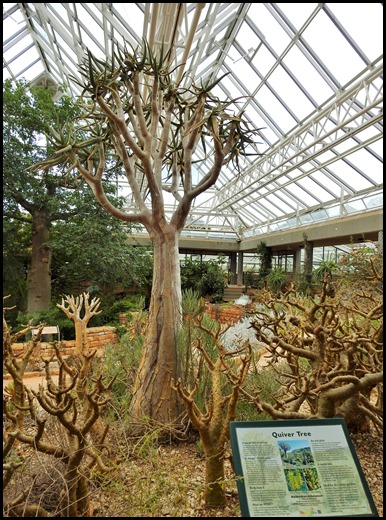

The Quiver

Tree (Aloidendron dichotomum): These species earned its

name, not because it trembles or quivers in the wind, but because in the old

days Bushmen hunters used branches from this tree to make quivers to carry their

arrows. They hollowed out the branch and covered the open end with a piece of

leather.

The Quiver Tree is Red Listed as

Vulnerable, it faces a high risk of extinction in the wild in the near future.

Climate change is the Quiver Tree’s greatest threat: as the climate warms and

dries the plants in existing populations are not coping with the change and are

dying. It was hoped that this species would move into more suitable areas south

and east of its current range but no new populations have been found. Scientists

predict that nearly three quarters of the population will disappear in the next

100 years if no new areas are colonised.

Sugarbirds and sunbirds feed on

the nectar in the flowers. And in the wild, communal weavers build their huge

nests (up to 500 birds), in the branches of the trees, where the young

are safe from jackals and other predators.

The Quiver Tree grows wild in

Namaqualand and Bushmanland, from Niewoudtville eastwards to Olifantsfontein in

the Northern Cape, and northwards to Brandberg in Namibia. It grows on

north-facing rocky slopes in the southern part of its range and on slopes and

sandy flats in the central and northern parts.

Other than making good quivers

the flowers can be eaten – they are said to taste like asparagus. The trunks

yields a kind of gum. The trunks of large dead trees are hollowed out and used

as natural fridges to store water, meat and vegetables – the fibrous trunk cools

the air as it passes through.

The Quiver Tree is a beautiful,

sculptural plant that would be an asset in any garden (I love the higgledy branches). It needs a sunny position in very

well-drained soil. A hot sunny rockery is best. It will also grow well in large

containers. Care must be taken not to overwater as it will rot if the soil is

poorly drained or constantly wet. Propagate from seed sown in autumn or

truncheon cuttings dried out for at least 3 weeks before planting. One for

my list and a good excuse for typing out all the info. So throughout the day

bimbling about in the Garden, I / we have gone from living in an apartment to

buying a house that now needs a conservatory, greenhouse, potting shed and

many big containers......

Loved the hole at the bottom of this

Candle Bush.

Our final

chap was rather lovely, no not Bear......the leaves looked as if someone

had glued them on to the stem as an afterthought. Cyptostemma currorii. What an incredible

hothouse.

ALL IN ALL SOME WONDERFUL

ODDITIES

REALLY WEIRD AND INTERESTING

|