|

Hummingbirds

We saw so many White-necked Jacobins at

Cuffie it made us want to know more about these fascinating little birds. For

some unknown reason this blogs layout has gone weird - tried seven times

adjusting and trying to make it right, but given up to get on with my life. Word

processor doing it's own thing, nothing to do with me, it looks perfect when it

it sent ???

Hummingbirds are birds comprising the family Trochilidae. They are

among the smallest birds and include the smallest extant bird species, the Bee

Hummingbird. They can

hover in mid-air by rapidly

flapping their wings twelve to ninety times per second (depending

on the species). They can fly backwards, the only group of birds able to do so.

Their English name derives from the characteristic hum made by their rapid wing beats. They can fly at

speeds exceeding thirty four miles per hour.

Diet:

Hummingbirds drink nectar, the sweet liquid inside flowers. Like bees, they

are able to assess the amount of sugar in the nectar they eat; they reject

flower types that produce nectar that is less than 10% sugar and prefer those

whose sugar content is stronger. Nectar is a poor source of

nutrients, so hummingbirds meet their

needs for protein, amino acids, vitamins, minerals, etc. by preying on insects and spiders, especially when feeding young. Most hummingbirds

have bills that are long and straight or nearly so, but in some species the bill

shape is adapted for specialized feeding. Thornbills have short, sharp bills adapted for feeding from

flowers with short corollas and piercing the bases of longer ones. The

Sicklebills' extremely decurved bills are adapted to extracting nectar from the

curved corollas of flowers in the family Gesneriaceae. The bill of the Fiery-tailed

Awlbill has an upturned tip, as in

the Avocets. The male Tooth-billed

Hummingbird has barracuda-like spikes

at the tip of its long, straight bill. The two halves of a hummingbird's bill

have a pronounced overlap, with the lower half

(mandible) fitting tightly inside the upper half

(maxilla). When hummingbirds feed on nectar, the bill is

usually only opened slightly, allowing the tongue to dart out and into the

interior of flowers. Like the similar nectar-feeding

sunbirds and unlike other birds, hummingbirds drink by using

protrusible grooved or trough-like tongues. Hummingbirds do not spend all day

flying, as the energy cost would be prohibitive; the majority of their activity

consists simply of sitting or perching. Hummingbirds feed in many small meals,

consuming many small invertebrates and up to five times their own body weight in

nectar each day. They spend an average of 10–15% of their time feeding and

75–80% sitting and digesting.

A huge thrill to get a shot of this little chap 'licking his lips'

Co-evolution with ornithophilous flowers:

Hummingbirds are specialized

nectarivores and are tied to the

ornithophilous flowers they feed upon.

Some species, especially those with unusual bill shapes such as the Sword-billed

Hummingbird and the sicklebills, are

co-evolved with a small number of

flower species. Many plants pollinated by hummingbirds produce flowers in shades

of red, orange and bright pink, though the birds will take nectar from flowers of

many colours. Hummingbirds can see wavelengths into the near-ultraviolet, but their flowers do not reflect these wavelengths

as many insect-pollinated flowers do. This narrow colour

spectrum may render

hummingbird-pollinated flowers relatively inconspicuous to most insects, thereby

reducing nectar robbing. Hummingbird-pollinated flowers also produce

relatively weak nectar (averaging 25% sugars w/w) containing high concentrations

of sucrose, whereas insect-pollinated

flowers typically produce more concentrated nectars dominated by fructose and

glucose.

Awake and catchin' forty

winks

Aerodynamics of flight:

Hummingbird flight has been studied intensively from an

aerodynamic perspective using wind

tunnels and high-speed video cameras. Writing in Nature, the biomechanist Douglas

Warrick and coworkers studied the Rufous

Hummingbird, Selasphorus rufus, in a

wind tunnel using particle image

velocimetry techniques and investigated

the lift generated on the bird's upstroke and downstroke. They concluded that

their subjects produced 75% of their weight support during the downstroke and

25% during the upstroke. Many earlier studies had assumed (implicitly or

explicitly) that lift was generated equally during the two phases of the

wingbeat cycle, as is the case of insects of a similar size. This finding shows

that hummingbirds' hovering is similar to, but distinct from, that of hovering

insects such as the hawk moths. The Giant Hummingbird's wings beat at eight to ten

beats per second, the wings of medium-sized hummingbirds beat about twenty to

twenty five beats per second and the smallest can reach one hundred beats per

second during courtship displays.

Metabolism:

With the exception of insects, hummingbirds while in flight

have the highest metabolism of all animals, a necessity in order to support the

rapid beating of their wings. Their heart rate can reach as high as 1,260 beats per minute, a rate

once measured in a Blue-throated Hummingbird. They also consume more than their own weight in

nectar each day, and to do so they must visit hundreds of flowers daily.

Hummingbirds are continuously hours away from starving to death, and are able to

store just enough energy to survive overnight. Hummingbirds are capable of

slowing down their metabolism at night, or any other time food is not readily

available. They enter a hibernation-like state known as torpor. Something Bear is getting more expert at by the

day. During torpor, the heart rate and rate of breathing are both slowed

dramatically (the heart rate to roughly fifty to one hundred and eighty beats

per minute), reducing the need for food - oh, Bear hasn't got to that part of

the manual yet then. The dynamic range of metabolic rates in hummingbirds

requires a corresponding dynamic range in kidney function. The

glomerulus is a cluster of capillaries

in the nephrons of the kidney that removes

certain substances from the blood, like a filtration mechanism. The rate at

which blood is processed is called the glomerular filtration rate (GFR). Most

often these fluids are reabsorbed by the kidneys. During torpor, to prevent

dehydration, the GFR slows, preserving necessities for the body such as glucose,

water and salts. GFR also slows when a bird is undergoing water deprivation. The

interruption of GFR is a survival and physiological mechanism unique to

hummingbirds. Studies of hummingbirds' metabolisms are highly relevant to the

question of how a migrating Ruby-throated Hummingbird can cross five hundred miles of the Gulf of

Mexico on a nonstop flight, as

field observations suggest it does. This hummingbird, like other birds preparing

to migrate, stores up fat to serve as fuel, thereby augmenting its weight by as

much as 100% and hence increasing the bird's potential flying

time.

Lifespan:

Hummingbirds have long lifespans for organisms with such rapid

metabolisms. Though many die during their first year of life, especially in the

vulnerable period between hatching and leaving the nest, those that survive may

live a decade or more. Among the better-known North American species, the

average lifespan is three to five years. By comparison, the smaller

shrews, among the smallest of all

mammals, seldom live more than two years. The longest recorded lifespan in the

wild is that of a female Broad-tailed Hummingbird that was ringed as an adult at

least one year old then recaptured eleven years later.

A rare glimpse for us of the Rufous-tailed Hummingbird, the Jacobin waits patiently in

line

Range:

Hummingbirds are restricted to the

Americas, from southern

Alaska to Tierra del

Fuego, including the

Caribbean. The majority of species

occur in tropical and subtropical Central and South

America, but several species also breed in temperate

climates and some hillstars even occur in alpine Andean highlands at altitudes of up to seventeen thousand,

one hundred feet. The greatest species richness is in humid tropical and subtropical forests of the

northern Andes and adjacent foothills, but the number of species found in the

Atlantic Forest, Central America or

southern Mexico also far exceeds the number

found in southern South America, the Caribbean islands, the US and

Canada. About twenty five

different species of hummingbirds have been recorded in the US, less than ten

from Canada and the same number for Chile. Colombia alone has more than one hundred and sixty and the

comparably tiny Ecuador has about one hundred and thirty species. The

Rufous Hummingbird is one of several species that breed in western North America

and are wintering in increasing numbers in the southeastern US, rather than in

tropical Mexico. Thanks in part to artificial feeders and winter-blooming

gardens, hummingbirds formerly considered doomed by faulty navigational

instincts are surviving northern winters and even returning to the same gardens

year after year. Individuals that survive winters in the north, however, may

have altered internal navigation instincts that could be passed on to their

offspring. The Rufous Hummingbird nests farther north than any other species and

must tolerate temperatures below freezing on its breeding grounds. This cold

hardiness enables it to survive temperatures well below freezing, provided that

adequate shelter and feeders are available.

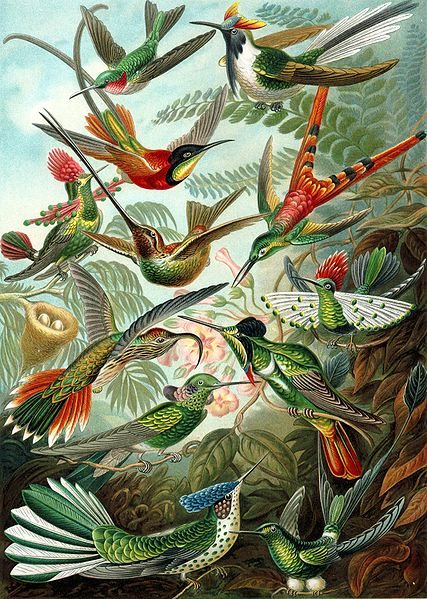

Hummingbird canvas. A colour plate illustration from Ernst Haeckel's Kunformen

der Natur 1899

Reproduction:

As far as is known, male hummingbirds do not take part in nesting.

Most species build a cup-shaped nest on the branch of a tree or shrub, though a

few tropical species normally attach their nests to leaves. The nest varies in

size relative to species, from smaller than half of a

walnut shell to several

centimeters in diameter. In many hummingbird species, spider silk is used to

bind the nest material together and secure the structure to its support. The

unique properties of silk allow the nest to expand with the growing young. Two

white eggs are laid, which, despite being the smallest of all bird eggs, are in

fact large relative to the hummingbird's adult size.

Incubation lasts fifteen to nineteen

days, depending on species, ambient temperature, and female attentiveness to the

nest. Their mother feeds the nestlings on small

arthropods and nectar by inserting her

bill into the open mouth of a nestling and regurgitating the food into its

crop.

Systematics:

There are between three hundred and twenty five to three

hundred and forty species of hummingbird, depending on taxonomic viewpoint,

historically divided into two subfamilies, the hermits (subfamily Phaethornithinae, thirty four species in six genera), and the

typical hummingbirds (subfamily Trochilinae, all the others).

One of the Nazca Lines in Peru, depicts a

hummingbird. We hope to see this in September

Feeders and artificial nectar:

Hummingbirds will either hover or perch to feed; red feeders

are preferred, but coloured liquid is not necessary and may be hazardous to

their health. Hummingbirds will also take sugar-water from

bird-feeders. Such feeders allow people

to observe and enjoy hummingbirds up close while providing the birds with a

reliable source of energy, especially when flower blossoms are less abundant.

Only white granulated sugar is proven safe to use in hummingbird feeders. A

ratio of one cup sugar to four cups water is a common recipe. Boiling and then

cooling this mixture before use has been recommended to help deter the growth of

bacteria and yeasts. Powdered sugars contain corn starch as an anti-caking

agent; this additive can contribute to premature fermentation of the solution.

Brown, turbinado, and "raw" sugars contain iron, which can be deadly to hummingbirds if consumed

over long periods. Honey is made by bees from the nectar of flowers, but it contains sugars

that are less palatable to hummingbirds and promotes the growth of

microorganisms that may be dangerous to

their health. Red food dye is often added to homemade solutions. Commercial

products sold as "instant nectar" or "hummingbird food" may also contain

preservatives and/or artificial flavors

as well as dyes. The long-term effects of these additives on hummingbirds have

not been studied, but studies on laboratory animals indicate the potential to

cause disease and premature mortality at high consumption rates. Although some

commercial products contain small amounts of nutritional additives, hummingbirds

obtain all necessary nutrients from the insects they eat. This renders the added

nutrients unnecessary. Other animals also visit hummingbird feeders. Bees,

wasps and

ants are attracted to the

sugar-water and may crawl into the feeder, where they may become trapped and

drown. Orioles, woodpeckers, bananaquits, and other larger animals are known to drink from

hummingbird feeders, sometimes tipping them and draining the liquid. In the

southwestern United States, two species of nectar-drinking bats (Leptonycteris

yerbabuenae and Choeronycteris

mexicana) visit hummingbird feeders

to supplement their natural diet of nectar and pollen from

saguaro cacti and

agaves.

In myth and culture:

Aztecs wore hummingbird

talismans, the talismans being

representations as well as actual hummingbird fetishes formed from parts of real hummingbirds: emblematic

for their vigor, energy, and propensity to do work along with their sharp beaks

that mimic instruments of weaponry, bloodletting, penetration and intimacy.

Hummingbird talismans were prized as drawing sexual potency, energy, vigor and

skill at arms and warfare to the wearer. The Aztec

god Huitzilopochtli is often depicted as a hummingbird. The

Nahuatl word huitzil (hummingbird)

is an onomatopoeic word derived from the

sounds of the hummingbird's wing-beats and zooming

flight. The Ohlone tells the story of how Hummingbird brought fire to

the world. Trinidad and Tobago is known as "The land of the hummingbird," and a

hummingbird can be seen on that nation's coat of

arms and 1-cent coin as well as

its national airline, Caribbean

Airlines.

ALL IN ALL AN INCREDIBLE LITTLE BIRD

THE MOST UNIQUE BIRD ON THE PLANET,

BEAUTIFUL

|