William Mariner

Beez Neez now Chy Whella

Big Bear and Pepe Millard

Fri 22 Nov 2013 23:57

|

William

Mariner

William

Mariner (1791–1853) was an Englishman who lived in the Tonga Islands from

the 29th of November 1806 to (probably) the 8th of November 1810. He dictated an

account of his experiences, An Account of the Natives of the Tonga

Islands, that is now one of the major sources of information on

pre-Christian Tonga – a masterpiece of Pacific literature. William Mariner was a fifteen year old ship's clerk aboard the

British privateer Port-au-Prince. The ship anchored off the Tongan

island of Lifuka, in the Ha'apai island group. Initially the captain and crew

were welcomed with barbecued pork and yams.

The

Port-au-Prince was an English private ship of war, a vessel of

five hundred tons armed with twenty four long nine- and twelve-pound guns as

well as eight twelve-pound carronades on the quarter deck. She carried a “letter

of marque” and this document permitted her Captain and crew to become pirates

against the enemies of England, primarily France and Spain. In payment for their

pirate raids any plunder they seized was to be their own. Commanded by Captain

Duck she sailed for the New World on the 12th of February 1805 having been

given a twofold commission by her owner, a Mr. Robert Bent of London. Their

primary goal was to attack the Spanish ships of the New World capturing gold and

valuables but if she failed in that task her secondary objective was to sail

into the Pacific in search of whales to be rendered for their oil.

The Atlantic crossing was rough but

uneventful and she lay off the coast of Brazil by April and then rounded Cape

Horn in July before proceeding north in search of Spanish Galleons laden with

treasure. They captured a number of ships but most yielded little in the way of

valuables and at times the men began to get disgruntled by capturing what they

contemptuously referred to as dung barges. The Port-au-Prince was now

also on the lookout for whales as well but, although catching a few, experienced

little success in this endeavour.

After leaving Hawaii in September

under the command of Mr. Brown, she intended to make port at Tahiti but missed

the port and sailed westward for the islands of Tonga instead. She arrived in

Ha’apai on the 9th of November 1806, almost two years after leaving England and

numerous engagements later, leaking badly and having witnessed the death of her

captain. She was laden with the spoils of war and cargo amounting to

approximately twelve thousand dollars, plus a considerable amount of copper,

silver and gold ore. A large quantity of silver candlesticks, chalices, incense

pans, crucifixes and images complemented the treasure. She weighed anchor for what was destined to be the last time in seven

fathoms water off the North West Point of Lifuka Island. A number of chiefs

visited the ship on the evening of her arrival and brought with them food gifts

and a native of Hawaii who spoke some English informing Captain Brown that the

Tongans had only friendly intentions. The Port-au-Prince also had some

Hawaiian crew who did not trust the situation and expressed concern to the

captain that the Tongans were feigning friendliness while planning attack.

Captain Brown chose to ignore the warnings, therein signing his own death

warrant and that of many of his crew.

The next day the natives began to

swarm the boat until there were around three hundred aboard in different parts

of the ship. They invited Captain Brown ashore to see the Island and assured of

their friendly motives he agreed. Setting foot ashore, he was clubbed to death,

stripped and left lying in the sand. Simultaneously, the main attack commenced

on the Port-au-Prince. The crew set fire to their ship, rather than

have her taken but were outnumbered and overwhelmed easily. The massacre was

brutal and swift seeing all but four of the crew members meeting the same end as

the captain, their heads so badly beaten as to be unrecognisable to the

survivors. Some of the cannons got so hot in the fire they began to fire causing

great panic amongst the Tongans. For the next three days the ship was stripped

of her iron, a valuable commodity, and her guns were removed before being burnt

to the water line to more readily remove what iron remained.

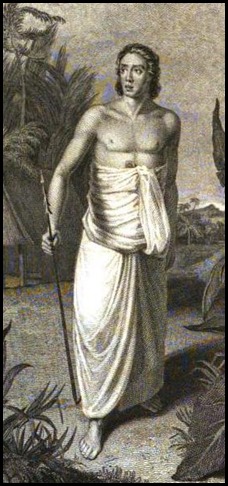

Mariner's sojourn in Tonga: One of the survivors was William Mariner, Chief Finau had taken a

shining to the lad when they first met aboard the Port-au-Prince.

William reminded the King of his son who had died of illness and when the attack

on the ship was being planned Finau had given instructions that the life of

Mariner should be spared if at all possible. William later pantomimed the an

explanation of why the cannons had gone off and through this, established a good

with the locals. He was renamed Toki 'Ukamea (Iron Axe) and Finau appointed one

of his royal wives, Mafi Hape, to be his adoptive mother. He spent the next four

years living amongst the islanders, learned the language well and traveled with

the chief, observing and absorbing the finer points of Tongan ceremony and

protocol. During this time he would witness the attempted unification of the

Kingdom by Finau using the very guns seized from the Port-au-Prince.

One long nine still lies on Ha’anno Island.

He also gave a lively

description of his lord and protector Fīnau Fangupō (ʻUlukālala II). One quote

from Mariner, giving Fīnau's opinion of the Western innovation of money, can be

found in paʻanga.

"If money were made

of iron and could be converted into knives, axes and chisels there would be some

sense in placing a value on it; but as it is, I see none. If a man has more yams

than he wants, let him exchange some of them away for pork. [...] Certainly

money is much handier and more convenient but then, as it will not spoil by

being kept, people will store it up instead of sharing it out as a chief ought

to do, and thus become selfish. [...] I understand now very well what it is that

makes the papālangi [white men] so selfish — it is this money!“

Chief Finau,

the king’s son gave permission for William to leave on a passing English vessel.

After rescue and his return to England Mariner had a chance meeting with an

amateur anthropologist called John Martin, to whom he told his story. Martin

wrote the book The Tongan Islands, William Mariner's

Account.

Mariner's books:

There are three major versions of Mariner's account. The original version was

first published in 1817 by John Murray II, with the help of Dr. John Martin, who

assumed authorship. Later editions appeared in England in 1818 and 1827 and in

Germany in 1819 and the United States in 1820. The Vava'u Press of Tonga issued

a new edition in 1981 that includes a biographical essay about Mariner, written

by Denis Joroyal McCulloch, one of Mariner's great-great grandsons, but leaves

out the grammar and dictionary. Two modern editions with modern Tongan spelling

and other additions have been published, the first by Boyle Townshend Somerville

in 1936 and the second by Paul W. Dale in 1996.

Tonga Islands: William Mariner's account : an

account of the natives of the Tonga Islands in the South Pacific Ocean, with an

original grammar and vocabulary of their language. Vava'u Press; 4th ed., 1981.

ASIN B0006EB4WI.

Will Mariner: A True Record of Adventure by Boyle

Townshend Somerville. London: Faber and Faber, 1936.

The Tonga Book by Paul W Dale. London: Minerva

Press, 1996. ISBN 1-85863-797-X.

ALL IN ALL A FASCINATING

STORY

VERY PROPHETIC COMMENT ABOUT

MONEY |