Early Settlers

Beez Neez now Chy Whella

Big Bear and Pepe Millard

Wed 6 Aug 2014 22:37

|

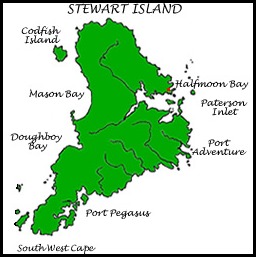

The Early Settlers of Island

Hill Homestead, Stewart Island

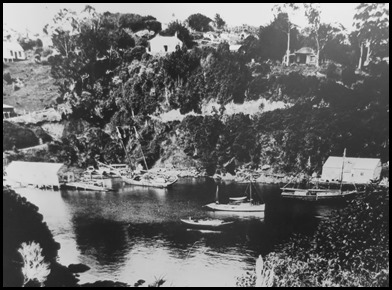

Halfmoon Bay with the early houses

of Oban.

The Department of Conservation has

managed to put together the story of one homestead on the island. Fascinating

social history. Challenging it may have been, but they

loved it. Lifestyle, a love of nature and the hope of ‘making a few shillings’

in lean times seems to have been common factors in bringing men and their

families to Mason Bay. For one hundred and eight years they pushed the

geographic, physical and economic limits of farming.

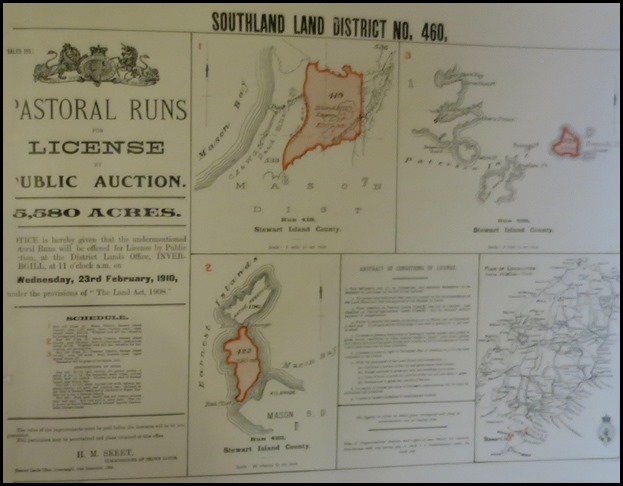

In 1867 the Commissioner of Crown

Lands, W.H. Pearson mapped a ‘paper town’ named Kilbride at the southern end of

Mason Bay. It was one of several settlements planned around the Stewart Island

coast in a deluded dream that became known as ‘Pearson’s Paradise’. Despite the

plan’s failure, Pastoral Run No.419 was advertised for auction in 1879. This

area of five thousand acres covered the drier dune land behind Mason Bay. In

1902, Run 533 was created to include the original settlement site of Kilbride.

This run, now five thousand, five hundred and eighty acres came up for auction on the 23rd of

February 1910.

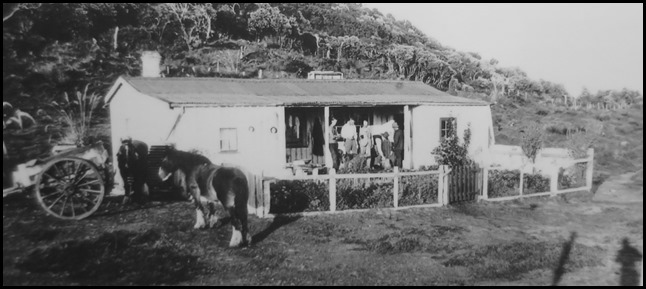

William Walker built the original Island Hill homestead.

William Walker was the first

runholder worked hard to dig drainage ditches and fence his stock, which he

increased to sixteen hundred sheep. He and his wife were known for their

hospitality, always offering a welcome on the mat, even if it was only made of

sack. They were here from 1879 to 1893.

Welles Orton Charlton was born in

Leicester, England. This titled Englishman married Laura Thompson, a Southland

widow. While he and his two stepsons farmed at Mason Bay – 1893 - 1913, Laura

stayed with her maids at the Traveller’s Rest above Harrold Bay, near Halfmoon

Bay. In 1902, William Thompson took up the new Kilbride Run while his brother

Cyril remained at Island Hill. One of Mrs. Thompson’s maids recalled beautiful

Christmas cakes baked at Kilbride during a summer visit, using black-backed

gulls’ eggs.

When Charlton and Cyril Thompson left

Island Hill, the run had a series of short term tenants, including Dr. James

Black, professor of chemistry at Otago University and sheep farmer John

Borne.

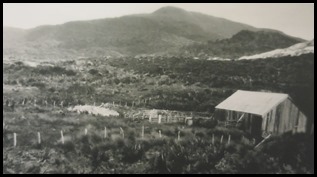

By 1926 the original homestead had been extended. Arthur Traill Junior. The Traill

family spent every spring and summer, 1923 – 1942, at Mason Bay tending their

flock of twelve hundred sheep – an eagerly anticipated annual adventure. Arthur

Traill supplemented their income by trapping possums, a newly introduced pest on

the island. For the remainder of the year, Arthur Traill was a

fisherman.

A Traill family

outing at Duck Creek, 1929.

The Leask

family. Back: Laurence Keast – friend, Peter and Ian Leask. Front:

Stanford, Dolly and Cyril Leask.

Stanford and Dolly Leask and their

family lived and worked here for twenty three years from 1942 to 1965, improving

the land until they were able to run fifteen hundred sheep. It was an advantage

that Stanford’s brother George farmed the Kilbride run next door.

In the absence of shops and freezers,

self-sufficiency was important. Meat was hung in a small meat safe, still

standing today. Sheep manure from the woolshed and bull kelp from the beach

helped to grow good crops of carrots, parsnips and potatoes.

The Leask, originally from the Orkney

Islands of Scotland built the woolshed in 1953. Its

timbers were gathered from the beach, mostly ‘dunnage’ used to hold a ship’s

cargo in place and chucked overboard at the end of a voyage.

Extra help was needed for the annual

muster and the children often played the part of sheep dogs. Fencing was another

challenge and despite a considerable commitment from the Mason Bay farmers, for

the most part sheep wandered freely over the run. Driftwood and fishing nets

featured in improvised paddocks. maintaining fences on the shifting dunes was an

added headache as they alternatively became buried or left hanging in the air.

Some of the bricks used to construct

the narrow sheep dip came from a chimney at the

Island Hill homestead............

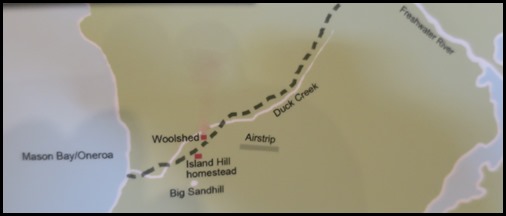

..........the remainder were shipped

from Halfmoon Bay to Freshwater Landing - just off

the map up Freshwater River where they were picked up by horse and cart. Stewart Island showing Mason Bay

and Paterson Inlet.

Once shearing was over, the hard part

began. Over the years, farmers tried a variety of ways to transport their wool

clip to Bluff or Invercargill – none of them straightforward. In the early

years, the main option was to cart the wool to Freshwater Landing and store it

in the sheds there. When the weather and tide were favourable, it was shipped

across Paterson Inlet to Halfmoon Bay.

Stanford Leask and his brother George

bought the Nightingale. This gave them another transport option.

Stanford carted the wool six miles from Island Hill to a large shed at Kilbride

where it stayed until the conditions were right. A horse and dray then took it

through the breakers to a waiting dinghy which rowed out to

the Nightingale. The journey continued across the nineteen miles

of Fovreaux Strait and Invercargill’s New River Estuary. The wool was finally

unloaded at a wharf where the Stead Street Bridge now crosses the Waihopai

River.

The Nightingale at Freshwater Landing. Leask’s Bay

1916, named after Tom Leask. This quiet bay has been the site of boat building,

a trying out depot and a fish cannery established in 1875.

A model dinghy

made by Alf Leask.

Island Hills’ last farmer, Tim Te Aika was in his element, mixing farm activities with

hunting, deer recovery and possum trapping. For his wife Ngaire, it was much

harder. She had to manage without electricity; home school their two daughters

and buy stores that would last for up to two months.

The ethic of ‘making do’ continued

until the end. A beachcombing discovery of wood staves from tallow barrels ended

up as the homestead’s picket fence.

Up to fifteen hundred sheep were

shorn here every summer. The shed was designed for two shearers working

side-by-side. By the time Tim took over hand shearing had been replaced by

electric clippers powered first by a tractor and later by an eight kilovolt

generator. It was the ‘bone of contention’ for Tim’s wife Ngaire that the

woolshed enjoyed electricity while their home had none...

Tim tried a third option for getting

the wool over to the mainland – by air. Landing a plane on the beach was

uncertain so he used his tractor to plough a six hundred metre airstrip through

the tussock grass. His son-in-law pilot flew in bags of superphosphate and

carried a bale of wool out. Even with family goodwill, it wasn’t economic. Today

the airstrip has fast been reclaimed by the tussock grass but the remains of

deep drains and buried fence posts are still visible.

Tim Te Aika gave up his lease to the

Government in 1986, after being here for twenty years, the last sheep were

removed the following year. The Department of Conservation now cares for the

homestead and its outbuildings as a historic resource that provides insight to a

fascinating chapter of island life.

The

workshop and the woolshed as they stand today.

Cared for in the main by volunteers.

The homestead

today.

ALL IN ALL PIONEERING AND

TOUGH

AN AMAZING

STORY |