SHB Pylon 1

Beez Neez now Chy Whella

Big Bear and Pepe Millard

Sat 27 Feb 2016 23:47

|

Sydney Harbour Bridge Pylon

Visit - Middle Level

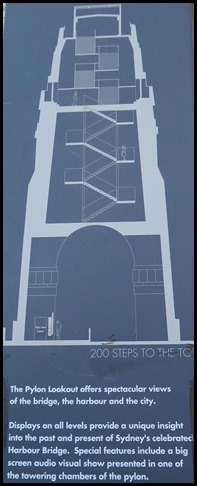

Part of our BridgeClimb ticket gave

us a pass to visit the Pylon Lookout, just two

hundred steps up to the top..... Seventy steps up we were surprised to find a

pay desk, small room full of information boards – a stained glass window up to

our left and the room beyond .......... a cinema...... begged us to spend a few

minutes catching our breath, sadly, the same film as we had seen before but it

gave us back a normal heart rate before we read all the boards.

“There can be little doubt that

in many ways the story of bridge building is the story of civilisation. By it,

we can readily measure an important part of a people’s progress.” Franklin

D. Roosevelt, speaking in October 1931.

It took a long time for the dream of

a bridge across Sydney Harbour to become a reality. Though many people believed

that a bridge was both desirable and necessary, there were many delays and

several heated battles before it was finally built. The ongoing disputes were

not restricted to whether the bridge was justified. Throughout the nineteenth

and early twentieth centuries, various ideas and schemes about what kind of

harbour crossing would be the most suitable were proposed and keenly debated.

“The expense of constructing a bridge from Sydney to the North Shore would

be but trifling compared with the benefits to be derived from such a

construction.” 1881 Petition to the Legislative Assembly requesting a

bridge linking Sydney to the North Shore.

Construction of a bridge linking

north and south Sydney seemed fated to be permanently on hold. One factor that

made the delay more viable was the existence, from the early 1840’s onwards, of

an efficient ferry service across the harbour. With

the opening of the railway between Milsons Point and Hornsby in the 1890’s, and

a steady rise in settlement on the north shore, the ferry service continued to

thrive and expand.

Reasonable road links had also been

established between the city centre and the northern suburbs in the 1880’s. Most

food and goods went via a circuitous route over the Gladesville Bridge. Given

these existing transport options, many politicians argued that the cost of a

bridge was just too high.

“O, who will stand at my right

hand, and build the bridge with me?” New South Wales politician Sir Henry Parkes’ election cry in the 1880’s.

Bridge or Tunnel: Debate about a

harbour crossing extended beyond questions of cost. The issue of what form of

harbour crossing would be most desirable also sparked controversy over the

years. Various schemes, designs, locations and concepts were mooted. From 1885,

for example, arguments raged over whether a bridge or tunnel would be best. A

Royal Commission considered the matter in 1890 and concluded that neither was

necessary. But between 1896 and 1899 four separate private members bills’ called

for either a bridge or a tunnel. All were rejected or lapsed following a change

in government.

In 1900 and again in 1903, tenders

were called for a Sydney Harbour Bridge. Norman Selfe’s design for a cantilever

bridge from Dawes Point to MacMahons Point was accepted in 1903 but later

dropped. By the early twentieth century, after decades of debate, schemes and

interminable delays, the bridge remained as remote as ever.

Getting serious: By the early 1900’s,

it was increasingly obvious that some form of harbour crossing was needed.

Time-consuming changeovers from transport links at either side of the harbour

were causing complaints and north shore residential areas were rapidly

expanding. In 1908, yet another Royal Commission recommended a bridge for

vehicles and pedestrians and a subway for rail traffic. In 1911, John Job Crew Bradfield, entered the fray.

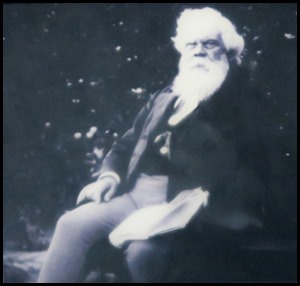

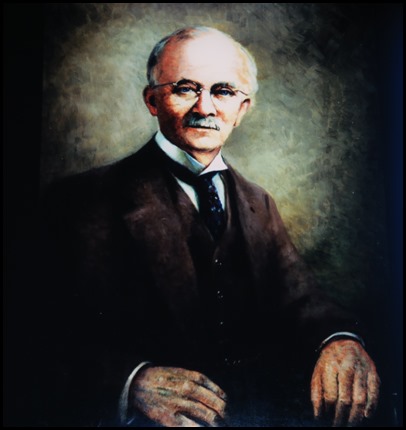

A photograph by me of a photograph by

Michael J Bradfield of a mid-1920’s portrait painted by Gerald Norton of Dr. Bradfield.

The ‘Father’ of the Bridge: Dr. John

Job Crew Bradfield [1867-1943], is the acknowledged ‘father’ of the Sydney

Harbour Bridge, having nurtured and guided it from concept to completion. Born

at Sandgate, Queensland in 1867, Bradfield earned a Bachelor of Engineering from

the University of Sydney in 1889, a Masters in Engineering in 1896 and a Doctor

of Science in Engineering in 1924. His working life began as a draughtsman with

the Queensland Government Railway. He then moved to the New South Wales

Department of Public Works, where he rapidly rose to the position of Principal

Designing Engineer. In 1912 he was appointed Chief Engineer of the Sydney

Harbour Bridge and Metropolitan Railway Construction.

Tender

Office.

In 1914, Bradfield

travelled overseas to investigate different bridge options, and was particularly

impressed by New York’s Hell Gate Bridge. In 1922, he again went abroad, this

time to investigate prospective tenderers. In the same year legislation at

long last authorised the construction of either a cantilever or an arch bridge,

to be integrated with road and rail systems on both sides of Sydney Harbour. The

dream was to be realised.

A man of talent and tireless energy,

Bradfield played a leading role in determining what type of bridge was most

suitable. He then capably and efficiently supervised its design and

construction. He and his staff checked and approved all of the detailed design

work, computations, drawings and calculations undertaken by Dorman Long and Co.

staff in England.

Although the Sydney Harbour Bridge

was Bradfield’s most celebrated monument, he was involved in numerous other

projects in the course of his long and illustrious career. There included the

Story Bridge over the Brisbane River and the Cataract and Burrinjuck Dams in New

South Wales.

“...you could never mistake

Doctor Bradfield walking down the shop, you’d –know him. He was a good bloke and

he – took pride, a great deal of pride in the work. He is recorded as saying

that he was proud of the workmanship, proud of the workers in the shop, that

they did a mighty job....”. Charles Brown, a ‘marker off’ in one of the

construction workshops, recalling J.J.C. Bradfield.

“I realised he was a dreamer. But

behind it all was his conviction he was planning the greatest City in the

Southern Hemisphere....” Jack Long, Premier of New South

Wales.

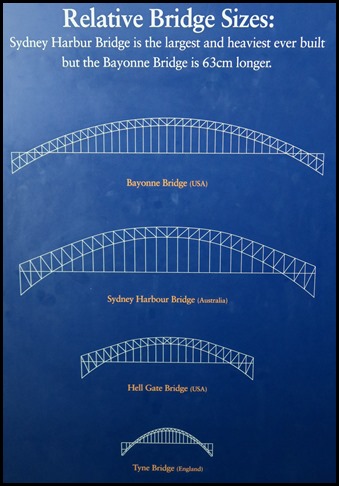

Strong and Handsome – The Winning

Design: When tenders closed on the 1st of January 1924, six companies from

around the world submitted twenty different proposals for a Sydney Harbour

Bridge. The winner was Dorman Long and Co. Ltd. of Middlesbrough, England. The

chosen design was a two-hinged steel arch with five approach spans at each end

and four pylons. At eleven hundred and forty nine metres long and with a forty

nine metre wide deck, it was estimated to cost the government four million, two

hundred and seventeen thousand, seven hundred and twenty two pounds. There were

practical reasons for choosing this type of bridge. Most importantly, a steel

arch provided strength, stability and rigidity needed to accommodate four

railway lines, six roadways and two footways. The selected bridge’s total

capacity was an estimated one hundred and twenty trains, six thousand cars and

forty thousand pedestrians an hour.

A steel suspended bridge, though

attractive, would not have offered the necessary load-bearing capacity. A

cantilever bridge, though economically and technically viable, was less visually

imposing than a steel arch. The winning design reflected the influence of New

York’s strong and handsome Hell Gate Bridge.

The construction of the Sydney

Harbour Bridge involved the use of fifty two thousand, eight hundred tons of

steel. From the 1870’s, when the world price of steel dropped by seventy five

per cent, a new era of bridge building opened up. Steel was so versatile, it

enabled established building methods to reach new peaks of development. Steel

not only provided its own possibilities of new forms, it also enabled concrete,

the other new material of the late nineteenth century, to evolve as an effective

medium.

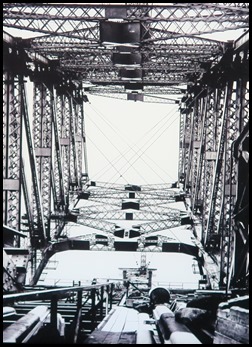

Designing the greatest steel bridge

in the world required skill and considerable ingenuity. Two major engineering

problems needed to be resolved at the outset. The first involved changes in

temperature. Steel expands as it warms up and contracts as it cools. To allow

for the fact that the top of the arch actually rises and falls about one hundred

and eighty millimetres due to temperature changes, hinges [two at each end] were

incorporated into the design. These hinges or bearings support the full weight

of the bridge, spreading their load through concrete skewbacks into a foundation

of solid sandstone. They also allow the bridge to move when the steel expands or

contracts.

The other problem was how to keep the

sides of the arch from crashing down while being built. One option was to place

temporary supports in the harbour but that would have been expensive and a

potential shipping hazard. The solution adopted was to hold each side back with

steel cables firmly anchored in thirty six metre long horse-shoe shaped tunnels

dug into the sandstone bedrock on both sides of the harbour. Each of the one

hundred and twenty eight cables weighed eight and a half tonnes and was made up

of two hundred and seventeen individual wires.

The joining concept was simple. When

the two spans were complete, the cables would be gradually loosened from each

end allowing the half arches to meet in the middle.

The successful tenderers, Dorman Long and Co. Ltd. signed a

contract with the government on the 24th of March 1924. Faced with an

undertaking of monumental proportions, their staff lost no time in getting

started. Lawrence Ennis, O.B.E.

[1872-1938], Director from 1924-1932 oversaw from the Dorman Long site office in

the Artillery Barracks at Dawes Point, the excavation and levelling of large

areas at Milsons Point, the construction and equipping of light and heavy

fabrication workshops on that land, where fabrication workshops would be

constructed and equipped; buying ships and building wharves where ships could

unload bulk steel, and the creation of a new town for the quarry workers at

Monuya. These were only some of the preliminary steps required. He then embarked

on the massive task of co-coordinating the complex construction

process.

Throughout the construction process, Ennis relied on the work of

designers, whose plans were translated into reality. The overall look of the

bridge owed much to Bradfield, but all of the detailed design was undertaken by

the contractors’ consulting engineer Ralph Freeman. His associate G.C. Imbault

was responsible for erection schemes for each of the designs.

The successful completion of the

bridge owed much to Freeman and Imbault’s talents and to their meticulous

attention to detail.

Ennis was generous in his praise of

the capabilities of Australian workmen. This helped foster a positive workplace

culture among the bridge workers. He once said, “Every day those men went to the bridge, they went.....not knowing

whether they would come down alive or not....”.

Construction of the Sydney Harbour Bridge began in 1924

during an economic boom. By 1928, however, the Great Depression had descended.

The outlook grew steadily darker:at its worst the New South Wales unemployment

rate reached 32.5%. The gloom only began to lift in 1933.

The bridge was often called the ‘Iron

Lung’ because it kept the economy breathing and so many people in work during

the eight years of its construction. Between 1924 and 1932, an average of

fourteen hundred people were directly employed on the bridge project at any one

time. Many more jobs, however, were provided by various sub-contracting

companies, which supplied everything from rivets to sand.

A stonemason - “Carrying my first

pay packet, I walked to the city to Gowings and bought a suit for three pounds,

ten shillings, a pair of shoes for eight shillings and eleven pence and a hat

for ten bob. I came out fully dressed.”

The Sydney Harbour Bridge contains

the heaviest steelwork of its kind ever constructed. The engineers involved on

the project needed to use innovative techniques and adapt them to meet the

special challenges presented in building the greatest steel arch in the

world.

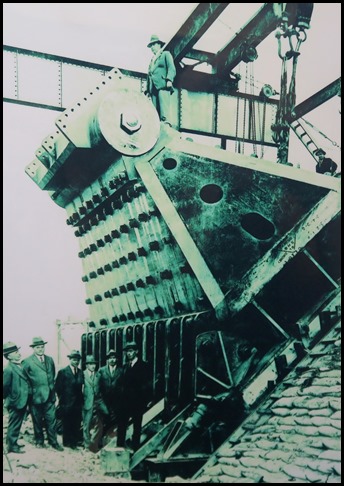

Above is a hinge

or bearing. The Sydney Harbour Bridge has four such massive hinges; two

at each end. These both support the full weight of the bridge, and allow it to

move when the steel expands or contracts due to changes in

temperature

Each bearing or hinge pin is a cast

steel rod four point two metres long and three hundred and sixty eight

millimetres in diameter. The pin is cradled in an enormous cast steel ‘saddle’

that transfers the load to the concrete skewbacks. Another saddle, upside down

and fixed to the bottom of the bridge, sits on top of the pin.

Made in England at Darlington Forge

Co. Ltd, the bearings each take a load of twenty thousand tonnes and weigh three

hundred tonnes.

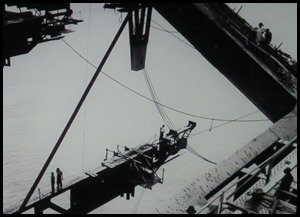

From Dogmen to

Tin Hares: Building the bridge required many different kinds of skills

and offered some uniquely challenging occupations. For example, ‘dogmen’ who

helped to co-ordinate the hoisting of loads often rode the steel up from the

barges, communicating all the while by telephone with the

crane-operators.

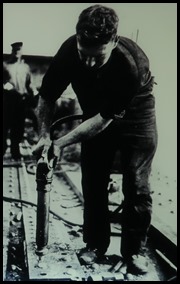

Riveting, in the workshops and on the

bridge, was done by boilermakers, each of whom worked with a special team. A

‘cooker’ heated up the rivets in a small portable oven, then threw them to a

‘mate’ or ‘holder up’ who caught them in a bucket and held the rivet in place

while the riveter worked on the other end.

Most of the steelwork was put

together by about one hundred and fifty riggers. However, there were only twelve

officially appointed ‘tin hares’ [six per side], who jockeyed each steel piece

into position, fastening the nuts and bolts and adjusting the angles before

riveting took place.

“I saw rivet cookers throwing the

almost white-hot rivets. They flew like sparklers through the air, shedding

burning scale everywhere, before landing in the catcher’s

bucket.”

Building the Sydney Harbour Bridge

was a perilous process. Basic protective gear of the kind now taken for granted

did not exist and safety precautions were few and far between. Men working at

dizzying heights enjoyed ‘no luxuries’ such as safety rails or nets. Neither

hard-hats nor ear-muffs were worn. Many iron workers and boilermakers later

suffered serious hearing problems from prolonged exposure to workplace

noise.

Those who laboured in the huge dark

box chords and girders were frequently showered with red hot scales of metal

from the rivets being hammered into place above them. They could also cut

themselves on metal shavings. Under these extreme conditions, overalls were

reduced to shreds in a matter of weeks.

“You had to

hang on by your eyelashes.” Tom Tomrap, one of the select steel erectors or

‘tin hares’ who, with the crane drivers, erected the bridge.

“ A bloke called Kelly fell a

hundred and fifty feet off the deck of the bridge into the water and survived

with two broken ribs. When they got him out his boots were split right open and

were up around his thighs. They gave him a gold watch.” Our guide, Alex,

told us this story on our BridgeClimb. Kelly had just two weeks off and was back

at work.....

“It was deafening and practically

no lighting at all and .... I used to stand on the heads of the rivets to try

and get a balance to hold the rivet in firm position..... The sparks used to fly

and I’d often have burns on my neck and arms......” George Evendon recalls

working as a riveter inside the chords of the arch.

“There were

six million rivets used in the bridge, in its erection and joining of the parts,

and in order to locate the holes which rivets go into, it was necessary to mark

those positions – you make an indent into the steelwork with a punch – that is

what is called ‘marking off’”. Charles Brown, who worked as a ‘marker

off’.

“....the men working for me

marked the holes in various angles and plates, it was my responsibility to check

them. Check every hole that they marked before the angles and plates were sent

to the drillers and I can virtually cross the bridge today and suggest that I’ve

had my ruler on every one of the holes that those rivets fill up.” Bert

Payne, Charge-hand marker-off..

Building Sydney

Harbour Bridge was a massive, multi-faceted and complex project. It

provided employment for a vast range of occupational groups, from surveyors,

engineers and draughtsmen to riveters, stonemasons, crane drivers, machinists,

labourers and many others.

The great majority of bridge workers

were Australian born or immigrants but an important group of skilled workers

from other nationalities were recruited, including Scottish and Italian

stonemasons, Irish and English boilermakers and machinists, and British and

European riggers.

Through the work was often demanding

and dangerous, the various bridge workers felt a special camaraderie and shared

sense of pride. Everyone was aware of the fact that the project would stand or

fall on the basis of the quality and precision of their

workmanship.

“I’ve never worked with a more

honest, hard-working crowd who were dedicated to their job. Their relationships

to each other were to my mind, excellent and I think they knew that they were

battling against the elements and against all the engineering problems to get

this thing across and I think it gave them more or less a common cause.”

Assistant Public Works Photographer.

Many of the tools

were very simple but in talented hands. Today bridge

workers are well protected and Health and Safety is uppermost. It costs

about three million dollars a year to keep the bridge good

condition.

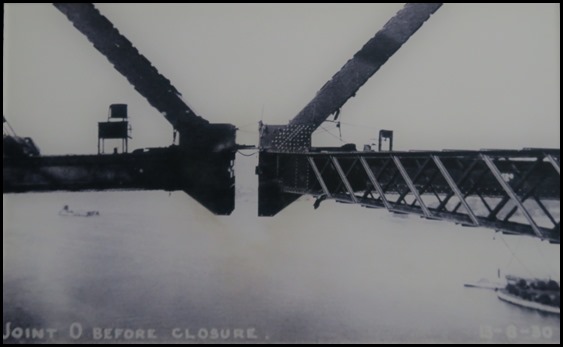

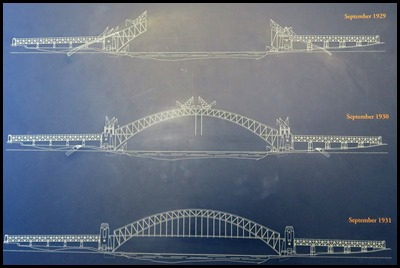

The Day the Arches

Joined: By the 7th of August 1930, the two half arches were finished. A gap of

only about one metre separated the two sides. Director of Construction Lawrence

Ennis laid a short plank across the gap and became the first person to ‘cross’

the Sydney Harbour Bridge. Having taken this historic step, he gave the order to

start slackening the tie-backs, so that the two half arches would line up and

join together perfectly.

This

crucial process took eight nerve-racking days. On the 13th of August, Sydney was

buffeted by a violent windstorm. But although the arches swayed perilously, they

withstood the test. By the 19th of August the two sides finally touched. They

soon separated however, as the day cooled and the

bridge steel contracted. After more work on the cables, they touched again at

ten at night. This time they remained joined and the arch was

complete. A signal was given and celebrations

commenced. The next morning the Australian flag and the Union Jack waved

triumphantly from the jibs of the creeper cranes. Vessels sounded their horns

and ferry passengers cheered as they passed what had, overnight, become a

bridge.

The Centre Pin: Suspended above the

main staircase is an original, half scale, plywood

model of the massive centre pin that was used to fasten the two half

arches together. The pilot pin is about twenty five centimetres square in

section. When the cables on both sides of the bridge were gradually released,

allowing the two half arches to come together, the pins on the south slotted

perfectly into opposite recesses on the north side.

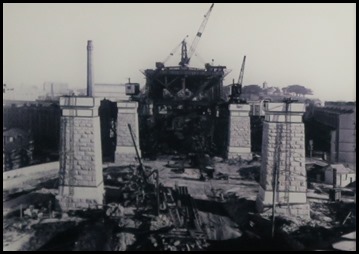

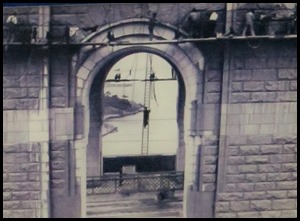

Rock from

Moruya: The pylons and the approach span piers of the Sydney Harbour Bridge are

faced with granite. At Moruya, three hundred and sixty kilometres south of

Sydney, Dorman Long and Co. built a new town to house two hundred and fifty

quarry workers and their families.

‘Granite Town’, as it came to be

known, soon included seventy two pre-fabricated wooden houses, a school, hotel,

post office and recreation hall. Many of its inhabitants were skilled masons

newly recruited from Scotland and Italy.

These were eighteen thousand cubic

metres of rock facings needed for the bridge. The stones were cut to size and

completely finished at the Granite Town quarry according to detailed sketch

plans. They were then numbered for fitting into place at the bridge site.

When the quarry closed, the town was moved to

Orient Point, and is still lived in by part of the local Aboriginal

community.

Functional and beautiful. The value

Dr Bradfield attached to the latter is revealed by his stance on the pylons. He insisted these be added to the original

design, largely because they would make the bridge more attractive. Though the

pylons’ immense weight does help firm the foundations, their function is

primarily decorative. Moreover, Bradfield insisted that to be suitably imposing

they needed to be faced with granite. Despite the fact that this involved

considerably more expense, about two hundred and forty thousand pounds, he

justified this on the grounds that only a “strong imperishable” natural product

like granite would “humanise the landscape in simplicity, strength and

sincerity.” Design of the pylons was undertaken by the consulting architects,

Sir John Barnet and Partners of London. Thomas Tait, the architect who carried

out the work, produced a stripped classical treatment with strong Art Deco

components.

“The bridge could have been built

without them, a massive iron structure of usefulness only.” Reverend Frank

Cash.

This is one of the original art deco

style lanterns used to light the Sydney Harbour Bridge. It was probably fixed to

the steelwork above the railway, but directed onto the road. All of the original

bridge lighting equipment was designed by the New South Wales Public Works

Department and contracted to Lawrence and Hanson Electrical Co. Ltd. of Kent

Street. However, the fittings were manufactured on subcontract by a group of

unemployed engineering graduates in a small leased factory in the Sydney

suburb of Alexandria.

The original bridge lighting was

installed by the NSW Government Railways, under Chief Electrical Engineer W.H.

Myers. It was powered from the Ultimo and White Bay power stations, through

substations at Argyle Street and in the north and south west

pylons.

Building the Sydney Harbour Bridge

captured the Australian public’s imagination. Steel and concrete construction

had never before been witnessed on so grand a scale. Photography was a

vital means of preserving this awe-inspiring engineering feat for posterity.

Though cameras were heavy and often unwieldy, and processing glass plate

negatives was time-consuming, there was widespread enthusiasm for taking

photographs in the late 1920’s and early 1930’s.

During the eight years of its construction, the Bridge attracted a vast

range of amateur buffs and professionals. However, the work of the three

talented photographers featured here – Robert Bowden, Henri Mallard and the

Reverend Frank Cash stand out for their accuracy and

artistry.

Henri Mallard: Where Bowden documented the

engineering details, Mallard, a founding member of the prestigious Sydney Camera

Circle, captured the workers and their culture. His ground-breaking industrial

photography resulted from shots taken among the workers themselves, and from any

height.

Robert

Bowden: As head of the Public Works Department team of photographers,

Bowden photographed all stages of demolition, excavation, fabrication and

construction. This enabled the engineers to keep track of the workers’ care and

accuracy. He and his assistants lugged their cameras along the arch and bravery

perched on steel beams to get required shots.

Reverend Frank

Cash: Every morning for a year, the Rector of Christ Church, Lavender Bay

[a former engineer] leapt from his bed to take a photograph of the bridge

reflected in the harbour. Parables of the Sydney Harbour Bridge, the volume that

resulted, was original and unique: part photographic portrait and part

engineering journal, liberally laced with biblical texts.

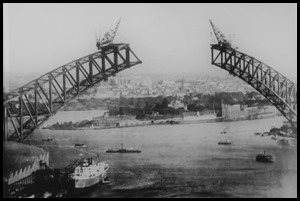

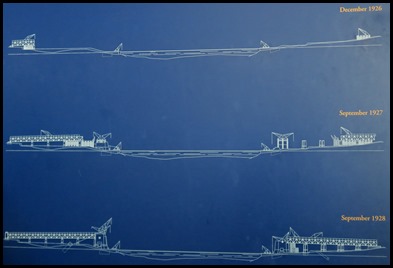

The bridge over the years of construction.

Stained glass windows are a

traditional method of decorating architectural spaces and permanently recording

events and characters from the past. The stained glass windows in this chamber

were created and installed in 2003. The appearance of the windows changes all

day long, light is reflected, illuminated and projected as the outside lighting

level rises and falls.

There is a

surveyor measuring levels, a concrete worker mixing

cement, a painter high up in the steelwork of the bridge, a rigger, a

stone mason working n the granite faced pylons, a riveter and the silhouette of

a dog-man high above the other workers. The glass artist was Robin Seville and

she describes her work “I was excited by the opportunity of producing

windows for such a grand space but also aware of the unique design and

structural challenges which existed. After many discussions with the designers

and much research I was sure that the approach had to be bold, colourful and

contemporary, but with an underlying Art Deco theme giving a sense of both time

and place. The characters portrayed are representative of many of the trades

involved in the making of the bridge, the poses are purposeful, even heroic. The

background of blue and grey represents their working environment – steel, sky

and water.”

ALL IN ALL SPLENDID

VISIT

STEEP STEPS AND TONS OF

INFORMATION |