Kings Creek

Beez Neez now Chy Whella

Big Bear and Pepe Millard

Thu 31 Mar 2016 22:47

|

The Gentle Kings Creek Walk

There was great excitement this

morning – we had a left turn............

Bear’s knee wasn’t up to ‘Heart Attack Hill’ when we arrived for the final walk of

our trip to the Red Centre. David checked everyone who was embarking on the Rim

Walk of Kings Canyon had three litres of water with them and off they went. We

watched and waited for our group to set off before taking ourselves along Kings

Creek.

Our group

with David keeping up the rear like a

sheepdog.

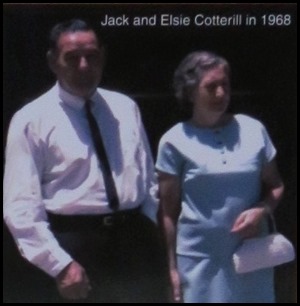

The Cotterill family pioneered

tourism here: Jack Cotterill was overwhelmed by the beauty of Kings Canyon when

Arthur Liddell, from Angas Downs Station, brought him here in 1960. Few people

knew of the place because there was no road at that time. Jack was

full of brave ideas for opening the area to tourism. The first task was to build

a road. Next he built a tourist lodge called Wallara Ranch at Yowa Bore, 100

kilometres east of the canyon. Elsie

Cotterill died in 1972 and Jack in 1976. Their sons John and Jim continued to

run Wallara until 1990. Then the family moved to Stuart’s Well, 90 kilometres

south of Alice Springs.

A memorial to ‘Jack Cotterill

whose foresight and effort made it possible for us all to visit this wonderful

place’. As happy little chaps watch

us.

By Camel and Coach: Only a

handful of white people had been here before 1961. There was no road to the

canyon and its wonders were largely unknown.

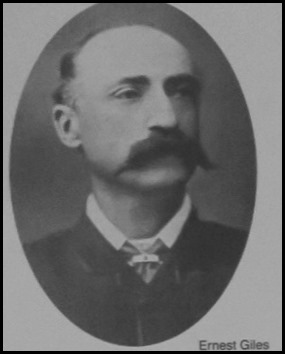

Exploring Our Desert Heart: 30

October 1872 was a momentous day for the Luritja people. The explorers Ernest Giles and Samuel Carmichael rode in from the west

and walked up the creekbed into the canyon. The Aboriginal people had never seen

white men or horses before.

Giles named the creek after an

old friend, Fielder King. He named the range after his brother-in-law George

Gill who helped fund the expedition. He wrote: “The country round its

foot is the best I have seen in this region: and could it be transported to any

civilised land, its springs, glens, ferns, zamias and flowers would charm the

eyes and hearts of toil-worn men who are condemned to live and die in crowded

towns.”

William

Gosse led another expedition into the area the following year. He camped

along Kings Creek before heading south to Ayres Rock which he named after

the governor of South Australia, Sir Henry Ayres.

Like Gosse in 1873, the Horn Expedition of 1894 used camels to cross the desert

sand dunes. Horses at Reedy Rockhole in the early

1920’s. The next visitors were a party

of distinguished scientists. The Horn Expedition of 1894 included experts on

flora, fauna, geology and anthropology. They were impressed with the biological

richness of the area.

Tempe Downs cattle station was

established on land east of the canyon in the late 1880’s. However, a run of bad

seasons followed. By 1896 there was little grass or water left on the property.

So the owners moved 2,500 cattle west at Reedy Rockhole and Kathleen

Springs.

Times were tough for the Luritja

people too. They needed to defend their precious waterholes and were soon

spearing cattle. The police responded by arresting a number of Aboriginal

people. Unlike the explorers, the cattlemen had come to stay. Life would never

be the same again for the Luritja people.

Tempe Downs cattle station

surrendered 1,059 square kilometres of land in 1983 so that a national park

could be established. Watarrka National Park was formally declared in 1989. The

Kings Canyon Resort opened in 1992.

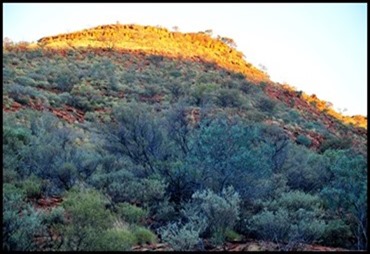

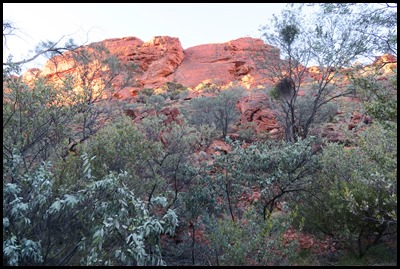

The sun tipped the

top of the creek and wow.

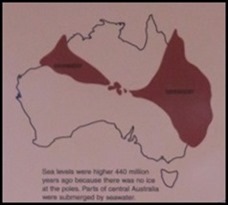

We had loads of information boards at

the beginning and along our route. Like old postcards, the rocks of Kings

Canyon provide clues to Watarrka’s ancient history. Living sea but dead land 440

million years ago. Imagine a surface like the moon, with not a single patch of

green to be seen. Rain scours the land. Great, brown rivers wash enormous

amounts of sand and mud into a shallow sea. This was Watarrka 440 million years

ago. They tell us that a shallow sea once covered this area.

There

is no ice at the poles and so the sea level was higher all around

the globe. The sea extended into central Australia from both the east and the

west. Red mud was washed down.

Ancient sand dunes: Conditions

had changed by the time the Mereenie Sandstone of the cliff tops formed. Imagine

a windswept plain covered with sand dunes this was Watarrka 400 million years

ago. Sea level has dropped and the waters have receded from central Australia.

The climate is drier but there are rivers flowing and freshwater lakes dot the

landscape.

Unbelievable upheaval: Central

Australia must have been a turbulent place 350 million years ago. Enormous

forces were being unleashed in the Earth’s crust. The pressure was greatest in

the Alice Springs region where the McDonnell Ranges formed. Huge amounts of

buried rock were buckled, broken and folded in a long, drawn out process lasting

millions of years. Here at Watarrka, the Carmichael and Mereenie Sandstone were

slowly pushed up. Huge forces pushed up the rocks of the George Gill Range and

cracked the brittle Mereenie Sandstone.

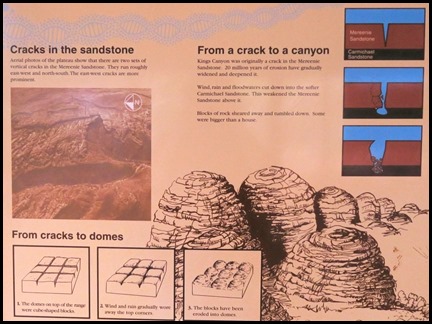

Aerial photos of the plateau show

that there are two sets of vertical cracks in the Mereenie Sandstone. They run

roughly east-west and north-south. The east-west cracks are more prominent.

Kings Canyon was originally a crack. 20 million years of erosion have gradually

widened and deepened it. Wind, rain and floodwaters cut down into softer

Carmichael Sandstone. This weakened the Mereenie Sandstone above it. Blocks of

rock sheared away and tumbled down. Some were bigger than a house. Colour

us happy, the diagrams at the bottom of the board show the domed rocks formed

just as the tessellated pavement did by seawater in Tasmania, but here it was

done by wind erosion.

The first half of our bimble was on

smooth ‘crazy paving’. Sadly we saw some bandaged trees – sacred to the indigenous peoples, where

numpties have scratched their names and damaged the trees. The next bit of the track was rocky but we could now see the

end of the creek.

Trees of the Creek Bed: Kings

Creek is a very special place for the Luritja Aboriginal Traditional Custodians

of Watarrka. They know it as Watarrka Karru (karru meaning creek), a ceremony

place on a native cat (quoll) dreaming track. In the Dreaming, native cat men,

kuningka, travelled from the southwest along this creek and had important

ceremonies at the foot of the waterfall.

“What I’m saying is that these

trees are really important. They are part of kuningka dreaming. Old Aboriginal

people didn’t try to break anything for making boomerang or bush tucker.... They

(tourists) can see him (the trees) but don’t touch anything. Just leave it. That

thing belongs here.” Aboriginal Traditional Owner. August 1995. Interesting

that a tree is a he.

‘Where the creeks run dry or ten

feet high..... And its either drought or plenty’. From ‘The Overlander’,

author unknown.

The trees here regularly have to

survive both floods and years of drought with little or no rains. After big

rains, you can find water under the sandy creekbed for many months. Young

saplings sprout and shoot up using this underground reservoir. The taller they

get, the deeper their roots penetrate into the sand and the greater the chance

they have of finding water during dry times. Being tall with deep roots also

means they don’t get washed away by floodwaters.

Living in a river bed isn’t

protection against severe droughts. During dry times, River Bed Gums can drop

limbs and most of their leaves to be able to survive. Hollows left by falling

limbs provide dwellings for many animals. We found the writings are almost

childlike.

Plenty to

read along the way.

A five minute break for Bear with one of the house sized rocks behind

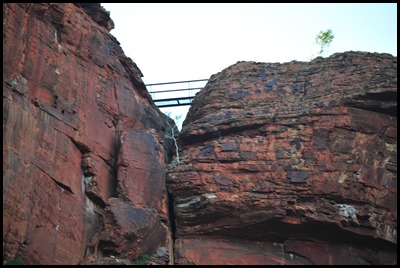

him. Above us the high sides of the

creek.

We bimbled as far as we could, to a viewing platform, there we took in the scenery.

High above us on

the left – a walkway.

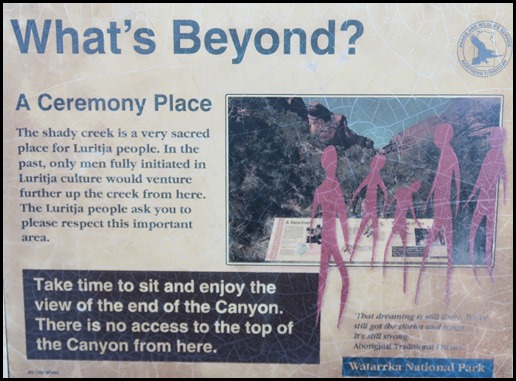

This is Luritja country. The

people have lived here for thousands of years and their culture remains strong.

As well as being renowned for its dramatic scenery. Kings Canyon is an important

conservation area. It has a very rich and diverse flora, including a number of

rare plants. The canyons permanent waterholes and moist gullies have sustained

the Luritja people through many severe droughts. These people say the rock formations were created by spirit ancestors

who are still present in the landscape. A

Ceremony Place: The shady creek is a very sacred place for Luritja people. In

the past, only men fully initiated in Luritja culture would venture further up

the creek from here.

A

Sanctuary: Aboriginal families used to camp near the entrance to Kings

Canyon. The men would have collected bush tucker and hunted only in the first

half of the Canyon, and would have been very careful not to disturb the

vegetation further up. In this way, special ceremony places often acted as

sanctuaries for wildlife. Men would have used spears for hunting Euros

(wallaroo), Black-footed Rock-wallabies, possums, Perenties and other

goannas downstream from here.

Spear shafts are made from

Spearwood vine, which grows in sheltered areas like this. The canes are

straightened over a fire. A sharpened mulga spear blade and barb are attached to

the spear with kangaroo sinew. When the spear pierces its animal (or human)

victim, the mulga barb detaches and penetrates into the body. A toxin in the

wood is also released into the victim’s bloodstream.

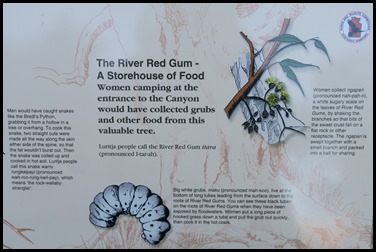

Men would have caught snakes like

the Bredl’s python, grabbing it from a hollow in a tree or overhang. To cook

this snake, two straight cuts were made all the way along the skin either side

of the spine, so that the fat wouldn’t burst out. Then the snake was coiled up

and cooked in hot soil. Luritja people call this snake warru rungkalpayi

(pronounced wah-roo-rung-karl-pay), which means ‘the rock-wallaby

strangler.

The River Red Gum (Itara to the

locals)– A Storehouse of Food: Women camping at the entrance to the Canyon would

have collected grubs and other food from this valuable tree. Big white grubs,

maku (pronounced mah-koo), live at the bottom of long tubes leading from the

surface down to the roots of River Red Gums. You can see these black tubes on

the roots of the tree when they have been exposed by floodwaters. Women put a

long piece of hooked grass down a tube and pull the grub out quickly, then cook

it in the hot coals.

Women collected ngapari

(pronounced nah-pah-ri), a white sugary scale in the leaves of the River Red

Gums, by shaking the branches so that bits of the sweet crust fall on the flat

rock or other receptacle. The ngapari is swept together with a small branch and

packed into a ball for sharing.

One last look back.

ALL IN ALL FABULOUS COLOURS

IN THE SUNSHINE

SO VERY

PRETTY |