Shell Museum, Dias Complex

Beez Neez now Chy Whella

Big Bear and Pepe Millard

Fri 10 Jan 2020 23:27

|

The Shell Museum and

Aquaria

We left the entrance in The Grannery

with it’s temporary display of Blue Print to isishweshwe material to bimble

across to the Shell Museum. This structure was erected in 1902 next to the Post

Office Tree as an extension of The Old Mill. The solid wooden pillars render a

special atmosphere to this edifice. The museum houses imaginative shell

exhibitions and portrays, for instance, the history of the use of molluscs by

man. Live animals are displayed in the natural habitat in aquaria. In through

the door we found an open tank with lobsters looking

up at us. The next tank held a giant hermit

crab.

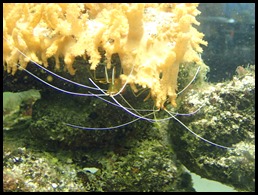

The tanks were beautifully clean. A

long one full of anemones and a cold water tank with

interesting chaps.

On we went to see abalone (Perlemoen – Haliotis midae) and giant turban (Alikreukel – Turbo sarmatieus).

This octopus was a snooty

surprise.

Indigenous giant African land snails and apple snails (fresh water).

A huge and beautiful hors-d’oeuvre or salad set made from baler

shells.

Crab,

starfish and an interesting looking

chap......

.......a shoveler

lobster, new one on us.

Nemo’s cousin,

cleaner shrimp and brain coral.

Tree coral,

a picasso and an anemone.

Bear

beside a giant clam. The Giant Clam (Tridacna gigas). Many giant

clams are classified as vulnerable according to the IUCN red data list. Several

aquaculture projects have aimed at increasing the numbers of giant clams. These

date back from 1985 to more recent and ambitious projects from 2007 – 2012.

Giant clams are particularly susceptible to the effects of environmental

pollutants and associated with the poisoning of humans who eat the flesh of the

clam. Strict harvesting quotas have been set.

Distribution: These are warm tropical in shallow

reefs in the Indo & South Pacific Oceans, usually in sand or on broken coral

fragments not more than 20 m below sea level. Major population declines are as a

result of overharvesting and

red tides resulting in their original distribution being significantly reduced

and becoming locally extinct in many areas where they formerly

occurred.

Ecology: Giant

clams are filter feeders, this serves to purify and clean the water, to an

extent. Coral reefs and their waters are generally nutrient poor – giant clams

have adapted to this by forming a symbiotic association with zooxanthellae.

Giant clams are unique among molluscs in terms of its fulfilling its nutritional

requirements: it simultaneously filter feeds and obtains nutrition by proxy from

photosynthetic phyto-algae.

Biology: Giant

clams belong to the phylum mollusca family Tridacnidae and are marine bivalve

invertebrates. Giant clams are the largest of all living bivalve molluscs to

have ever lived, at least according to fossil records. Giant clams grow to

almost 130 cm, and can weigh up to 500 kg. The giant clam on

display measures 106 cm wide by 63 cm tall. Giant clams are hermaphrodites – unable to self-fertilise. Giant

clams may spawn for decades releasing hundreds of millions of eggs on a single

expulsion. Lab studies show that giant clams can grow up to 120 mm per year;

however wild clams which are not optimally fed may grow significantly

slower.

Myths: Known

previously as “man-eater” or “killer” clams historically; however the clams

close slowly instead of ‘snapping shut’ giving divers just enough time to react

and remove their limbs before becoming trapped. Giant clams don’t necessarily

take hundreds of years to reach their massive size, as previously believed.

Records have shown that a clam of 500 kg can obtain its size within 63

years.

Human Use &

Trade: They are consumed as an aphrodisiac. The flesh is enjoyed as a delicacy

and the shells are sold on the black market for ornamental use. Recent studies

conducted by an Italian team found high amino-acids associated with increased

sex drive in humans, and very high levels of zinc, instrumental in the

production of testosterone in men. They are highly prized in the tropical

aquarium market.

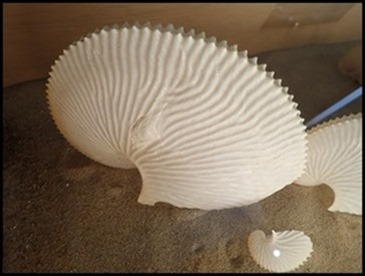

Upstairs a very comprehensive

collection of shells by the hundred. Larry and Marlo’s first trip to these

museums and often we heard the enthusiastic collectors chatting in delight. and

plenty of “Oo Larry” at something new or interesting. Too many to go through I

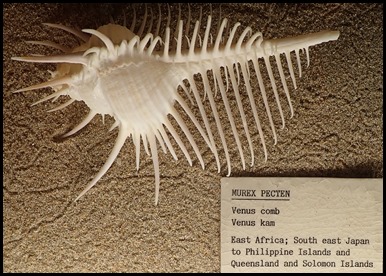

chose my favourite two, the Argonauta Argo or paper

nautilus and the Venus comb.

Dangling from the ceiling was a Cameroceras. This life-size model of a Cameroceras was

created as part of a special program during October 2016 (Marine Month). Estelle

McIlrath, a volunteer and excellent visual educator trained and guided a team

from the local Youth Centre (Department of Correctional Services) in creating

this life-size model, mainly from paper mache and other recycled materials. We

thank all who were involved with creating Mossel Bays’ own Cameroceras!

Below this giant were many paintings done by local schoolchildren and some

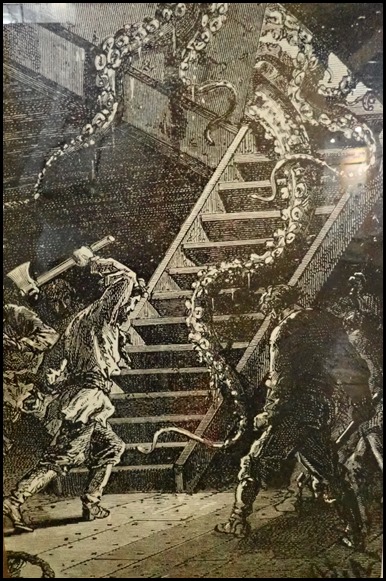

were truly exceptional. I went back downstairs as Bear told me there was a write

up about krakens, the creature from so many horror films.

The

Kraken: many-armed sea monsters feature in the ancient literature of

several maritime nations. The most notorious of these creatures is the Kraken of

Scandinavian legend. The Kraken was considered by most scientists to be entirely

fictitious until in 1873 part of a tentacle was presented to the Rev Moses

Harvey of St Johns, Newfoundland, by fishermen whose boat had been attacked and

nearly sunk by a Kraken. Later strandings have provided much information about

this “living legend” now known as the Giant Squid

Architeuthis.

Architeuthids live at great

depths and normally surface only when injured or dying. Consequently little is

known of their habits, However, it is clear that they are frequently eaten by

sperm whales, Physeter catadon, and are occasionally swallowed whole. Whale

fisheries and researchers commonly find giant squid remains in the stomachs of

slaughtered animals and on one occasion a whale harpooned off Madeira vomited a

10,2 metre squid which was still alive. Most sperm whales bear the scars of wounds inflicted by powerful

tooth-edged squid suckers suggesting that Architeuthis is a formidable adversary

when provoked.

Although the largest squid

recorded had a mantle of 3.5 metres giving a probable total length of 18 metres

and a weight of over 1,000 kg, it is thought that larger individuals may exist.

The 9.6 metre long model on display in this museum is based upon a specimen

washed up on Sea Point Beach.

Size of Cephlapods: There

is great size variation between different species of Cephlapods: the cuttlefish

range from a length of 375 mm (Hemisephias typicus) to over 1.5 metres (Seria

latimanus). The smallest octopus speciaes, Octopus arborescens, has a span of

only 50 mm while the largest, Octopus hongkongensis, reaches over 9.5

metres. The greatest size variation from is found among the squids which range

from 20 mm (Sandalops pathopsis) to 18 metres

(Architeuthis).

Intelligence: Octopuses and

squids are the most intelligent of all invertebrates. The octopus brain consists

of three lobes, one of which is responsible for learning and memory retention.

These faculties are aided by efficient vision. The eye is similar in structure

and function to that of the humans.

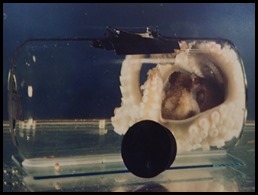

In experiments at Miami

University, “Lee” learned to remove a cork from a jar

to reach inside for a prawn. She later climbed into the bottle for the next

morsel.

The

Abyss: Beyond the depths where sunlight can penetrate to support algae,

animals are either carnivores or scavengers, feeding on each other or on

detritus sinking from the plankton above. The greater part of the deep ocean bed

appears sparsely populated. Molluscs are mostly represented by burrowing

filter-feeders about which little is known. In volcanic regions the ocean floor,

deep fractures in cooling lava allow seawater to penetrate the earth’s crust.

Minerals from crustal rocks are picked up while sulphate in the water is changed

by heat and pressure into hydrogen sulphide. Flowing back through fissures to

the ocean floor, the water brings sufficient warmth and chemical “food” to

support a rich bacterial growth. This in turn nourishes larger organisms

including limpets, mussels, giant clams and crabs which are preyed upon by

carnivorous fish and octopuses. Thus an energy source other than sunlight

triggers a chain of life in an otherwise hostile environment.

Deep sea squids: Many deep sea

squids possess light organs: these may be simple structures consisting of lens,

light-producing tissue and a reflector. Others, such as Lycoteuthis, are

equipped with diaphragms, focusing mechanisms and colour

filters.

The function of such organs is

not fully understood: perhaps they are useful in keeping schools together in the

deep-sea darkness, perhaps they help to attract prey, or to deter predators, or

to attract mates.

More lobsters for a colourful end to this

really interesting museum and aquaria.

ALL IN ALL A SPLENDID

EXHIBITION

BRILLIANTLY LAID

OUT |