Albatross Centre

|

The Royal Albatross

Centre

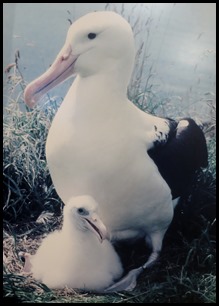

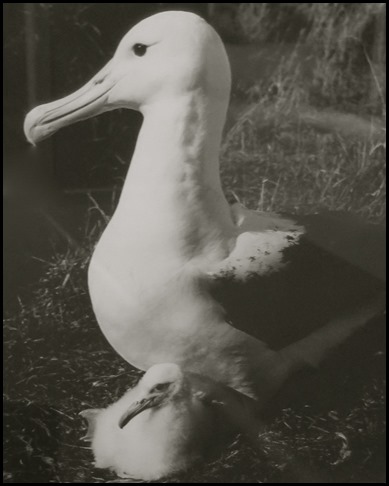

The royal albatross D1 – on the right,

later known as Grandma with her mate D4. This picture

was taken by Dr. Lance Richdale in December 1938, he banded Grandma in 1937 when

she had reached breeding age. She was the star of her own television documentary

and set a world age record. She was at least sixty one when she went missing in

mid-1989. Her chick of that season called Button, survived through supplementary

feeding by the colony’s rangers and went on to have chicks of his own. The

picture on the right is the last one taken of Grandma, she stands patiently

whilst head ranger Shirley Webb weighs Button in February 1989. We began our

tour with guide Chris, who showed us a film where we learned of this

extraordinary bird, a good mother who married, divorced, married, widowed,

married, widowed and then went back to her first husband D4. Perhaps Liz would

have been a more appropriate name for her, actually her different husbands was a

benefit to the early formation of the colony by increasing the size of the gene

pool. We were also told that whilst she was good with the rangers, her son

Button is not, he attacks at every opportunity and proves to be grumpy, but a

good father.

This Northern Royal

Albatross chick left Taiaroa Head on the 26th of September 2006. It was

found two days later and preserved in memory of those chicks who grow to

adulthood.

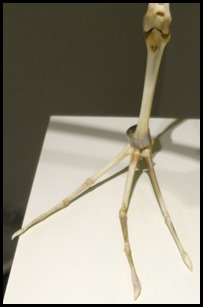

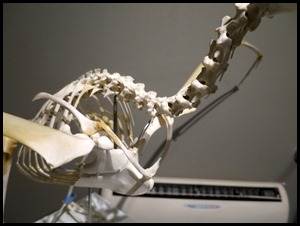

The skeleton in the corner gave us a unique look at the

form of this amazing bird.

While Chris offered coats to the group as

we now had to face the biting wind outside, we looked at the model of an albatross. What full

wingspan looks like beside Bear and I held an

egg. We were well wrapped up and bimbled along behind.

After a steep climb, we looked back on

the Albatross Centre.

Inside the viewing house we looked down on

a ball of fluff, a baby

preening and one stretching his

wings.

Bear held a fluffy chick that demonstrated just how heavy a five

month old was. Chris explained the record chart,

incredible to see the ages of the parents. He told us how duct tape and nail

polish could help if an egg got accidentally cracked by a clumsy parent and that

there were two same sex pairs, one acting as foster parents and one where the

egg layer had lost her husband and another lady was helping out feeding the

chick. We did see an adult

circling but it was too much to hope that we saw a chick being

fed.

A chick can take two and a

half kilograms at a single feed. If parents cannot manage and the chick is not

up to weight for age, the rangers supplement feed in between parent visits. A

little salmon as it is too rich for them but most other fish and mainly squid.

The picture shows just how wide they can say arrrrr.

Chris told us how hard the rangers work to eradicate

rats, weasels and feral cats from the

hill.

Also on the hill we could see black and spotted shag nests, sharing space happily with

red-billed gulls.

After a long time watching

the activity on the hill, we went for the ‘Gun’ part of our tour, after that

back down to the centre. Outside we stopped to look at a

variety of wingspans, their names in Māori are: toroa, kawa-mapua,

karoro, tarapunga and tiu.

Time to bimble around the centre.

Northern Royal Albatross are on record as

having laid the first egg at Taiaroa Head around 1920. However, with so much

interference from people and predators, it wasn’t until 1938 that a chick

fledged successfully. This was mostly due to the efforts of Dr. L.E. Richdale, a

Dunedin ornithologist. In 1951 a full-time field officer, Stan Sharpe, was

appointed to protect the albatross. Ever since then, work at the colony has

remained ongoing – resulting in the longest continuous study and protection of

any animal population. Each albatross in the colony has leg bands for

identification purposes, which allows the life story of each bird to be recorded

by Department of Conservation rangers.The colony is intensively managed to

ensure its survival and to assist the overall population growth rate, which is

naturally slow.

Protection of the birds from introduced

predators such as feral cats, rats, ferrets and stats can be challenging. Other

threats to the colony include climatic extremes, fire and disturbances. The

natural curiosity of visitors can have a damaging effect, so public access is

limited to guided tours. The Department of Conservation allows the Otago

Peninsula Trust to conduct small guided tours up to an observatory within the

reserve to view a section of the nesting area at certain times of the year. With

ongoing study, minimal disturbance and protection, the colony will continue to

grow.

1920 First albatross egg laid at Taiaroa Head

1938 First albatross successfully fledges

1972 Public access by guided tour to colony commences

1989 Royal Albatross Centre opens

2007 500th chick hatched

2014 500th chick makes first return Taiaroa Head.

April and July chicks

A year in the life of a Royal

Albatross:

September: New

season’s parents start arriving to re-establish their pair bonds before mating.

Last season’s chicks fledge.

October:

Some breeding pairs may still be arriving. Mating takes

place.

November:

Nests are constructed of loose vegetation and an egg is

laid.

December: Parents

share incubation duty over eleven weeks – one of the longest of any bird. One

bird stays to incubate the egg, one goes to sea to feed.

January:

Incubation continues – some chicks may start hatching toward the end of

the month.

February:

Hatching takes on average three days for the chick to emerge from the

shell.

March:

Parents take turns to feeding and sitting on the chick to guard it for

the first thirty to forty days.

April:

Parents leave chicks on their own and return separately to feed them

every two to four days.

May – July: Chick

rearing continues.

August:

Chicks become more active walking around at times, parents are

returning less frequently to feed the chick.

September: Chicks

fledge, they are gone for four to six years on average. Parents leave the colony

to spend a year at sea before returning to breed again the following

year.

Toroa is the Māori name for

albatross.

The albatross wing span is up to ten feet

long.

Albatross can fly at speeds of around

seventy five miles an hour.

At seven months old, the chick weighs

twenty two to twenty four pounds – an adult averages eighteen to twenty one

pounds.

Spending more than 80% of their lives at sea, Royal Albatrosses cover

vast distances. From an early age they are able to fly right around the Southern

Ocean between latitudes thirty and sixty degrees south. There the westerly winds

are strong, persistent and suited to long distance gliding flight. The usual

range is five hundred kilometres, but a thousand kilometres a day is possible.

Most albatrosses nest on oceanic islands. In sub-Antarctic region they choose

places that humans would consider inhospitable – cold, wet and wind-swept. The

southern subspecies of Royals nests on the tussocks of Campbell Island and the

Auckland Islands of Adams and Enderby. The northern subspecies favour a warmer

climate and makes its home on outlying islands of the Chatham Islands and here

at Taiaroa Head. After the best part of a year spent off South America the

albatross return to New Zealand waters in September and October via the South

Atlantic and Indian Oceans. Paired birds may arrive within hours of each other,

but usually males come home first. Juvenile Royals, in their first year disperse

around New Zealand waters and eastwards across the Pacific to South America, GPS

tracking has shown they even visit the Chatham Islands but never join that

colony, always returning to their natal home.

Who’d have thought it. Lice.

Of the fourteen types of albatross we are thrilled to have seen

Royal, northern and Southern. Wandering, Snowy, Gibson’s and Antipodean.

Mollymawks, black-browed, white-capped, Salvin’s and Buller’s. Lastly, and

perhaps our favourite as they were our first, the waved albatross of the

Galapagos Island, Espaniola. I have to say the Royal is

very impressive and the Buller’s is very pretty. Sadly, so many of these magnificent birds feature on the

endangered and critically endangered lists.

Debris in the

North Pacific – yellow dots on the map, is concentrated in two huge eddies,

gyres. In these areas the surface water contains six times more plastic than

plankton by weight. Albatross breeding on Hawaiian atolls ingest the plastic,

probably mistaking it for food, and the feed it to their chicks. Thousands of

chicks die every year in Hawaii because their stomachs fill with plastic leaving

no room for real food. Sadly, the dead Laysan

albatross chick above was found on Midway

Atoll, Hawaii. Laid

out – it looks horrific.

Peter Moore of the DOC took the picture of

this Southern Royal with fishing line protruding from

his gape. Stacy Moore DOC took the picture of regurgitated plastic next to a

nest. Chrissy Wickes DOC took the picture of this Southern Royal with a hook through her leg. Just Terrible.

Now for happier stuff. There is a

question which has long intrigued scientists. Reports of albatrosses feeding at

sea are rare. Mostly it happens at night. Deep living luminescent squid, which come to the surface after dark, form a major

part of the albatross diet along with scavenged fish. Squid beaks are often

found regurgitated near the nests here, just before the chicks fly off – an

instinctive action to clear their stomachs.Albatrosses can dive just below the

surface to about ten feet down, they hook and chop up their food using the

‘forceps’ of their long beaks.

Peculiar to the Taiaroa Head albatrosses is a taste for octopus. Since octopus tend to confine themselves to the seabed it remains something of a mystery how the birds here catch significant numbers of them.

Creatures of Myth: Are albatrosses friends or foe ??? Are they departed comrades watching over shipmates at sea ??? Are they the souls of sailors condemned to haunt the waves forever ??? I was told as a child that when I ate soft boiled eggs, I was to upend the empty shell, tap it with my teaspoon right way and pierce the egg with the other end of the spoon. By doing this I was releasing the soul of a fisherman to heaven from an albatross. I have never not done this. When Bear and I got together, I told him and he has done it ever since. There is mild panic if after the tap stage the inner bit is tough and doesn’t pierce, it has to be done before the egg shell smashes. Phew, always managed. Superstitious clap-trap ??? Who knows but all we can tell you is we have released a fair few souls. Egg events can cause a bit of a problem, but I’m brave and wouldn’t fail in the task. We’ll leave this amazing place with a picture of Grandma.

ALL IN ALL SO

SPECIAL

WONDERFUL |