Buller Tramp

|

Buller Gorge Tramp

We set off from the bridge for our

last bimble of the day, but as the gates are locked at five we had to speed up

to a tramp to get round the loop. The 'normal' flow

of the upper Buller River at the Longford data recorder north of Murchison is

fifty six cumecs. By the time

the Buller reaches the bottom of the Four Rivers Plain, normal flow is

approximately one hundred and ten cumecs. In October 1998 a flood

of one thousand, three hundred and eighty cumecs – to Bears

armpit in the picture, was recorded at the Longford recorder and

the upper Buller River reached six point two metres or over twenty feet, then

the highest level since recording began in 1964. One cumec is equivalent to

35.3147 cubic feet per second. The 1998 figure was

paled by 2011 – above index finger, the next marker up in 2012 and the top

marker recorded in 2010 or above the lowest trees on the

bank opposite.

The track took us along the edge of the White Creek Faultline. On the 17th of June 1929 the land was thrust upwards at this point, instantly creating the 4.5 metre drop in the trees beside us. The earthquake measured 7.8 on the Ritcher Scale. Down the track I sent Bear to get him lined up with the 2010 marker, the water would have come over his head and that doesn’t take into account that we had walked uphill since the river itself.

Out in the open once more and what did we see, a little treacle, lovely surprise. Sad to think she is underwater during floods.

A quick look at ‘her bits’ and onward to some information boards.

Goldmining 1880’s: With a supply of high-pressure water, miners were able to employ their favourite method of working – hydraulic sluicing. Powerful jets of water were played onto terraces, cutting them down and washing them away. Large rocks were rolled aside and neatly stacked while gold-bearing gravels passed into timber sluice boxes. Gold was trapped by wooden bars. Lighter stones carried on down a deep channel called the tail race to the river. When the process was completed, nozzles and undamaged pipes were taken to other claims, unsound pipes were left to rust and the original native plant species left to regenerate. Serving a scattered population of miners, the White Creek settlement never grew to the size of Lyell or Hampden – now Murchison. While those towns were important supply centres with many shops and hotels, White Creek had tents and shanties, plus one of the small post offices situated at intervals along the main road. There were miners of many nationalities, including Chinese such as Lai Lum who worked a claim a short distance downstream on the other side of the river. Numbers of women and children increased later in the 19th century. A transition from mining to farming that occurred on other gold fields was limited here in the gorge by a shortage of flat land. Some who did work the land still needed to supplement their incomes by working gold claims – including here on the peninsula where water was piped across the bridge to unworked areas of ground. For tent dwellers of the 1890’s the greatest comfort was usually a handy hotel. From White Creek that would mean a four kilometre trudge down the gorge to Newton Flat. Tents were pitched once again on the peninsula when victims of the 1930’s depression tried their luck. The depression brought unemployed men who sought an existence on gold that had been missed before. Another revival came in the 1970’s when testing for gold found all samples collected contained some angular fragments, suggesting that these had not travelled far down the river from their source. No local mother load had been found.

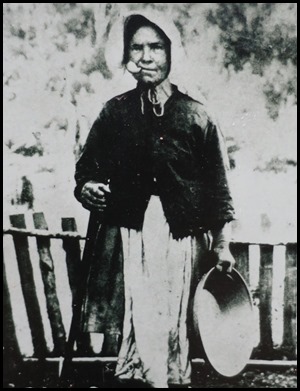

Biddy of the Buller. One of the gorge’s most famous characters, Biddy lived in the hope that one day she would find the ‘mother load’ or at least a sizeable chunk from it.... Biddy dug on the river for twenty three years........

We crossed the faultline again and Bear got stuck in to the next lot of fascinating information.

1. Looking across the Buller River to the earthquake displacement on the peninsula – we are standing at the bottom of the displacement. 2. Large areas of forest were left devastated, and mud blocked streams and rivers. 3. Landslides within the gorge were extensive, as seen in the picture near the Iron Bridge.

During the days leading up to the 17th of June 1929, colossal natural pressure built up on the many faultlines that run run like veins through the north-west Nelson region. Somewhere along that system, at 10:17am, the strata finally gave way, taking the stress along other faults to snapping point. The result was an earthquake measuring 7.8 on the Richter Scale, felt nearly all over New Zealand and causing massive devastation through Nelson and the West Coast. Although the event has been best known ever since as the Murchison earthquake, there were also epicentres well to the east, west and north. The most dramatic example of the earth’s movement was seen right here along the White Creek Faultline. On the eastern side of the fault, the earth was thrust 4.5 metres upward. On the other side of the river the upthrust formed an impassable barrier to traffic. Re-forming the road around this and many other quake-formed obstacles took several months. Elsewhere in the Buller Gorge fissures opened in the ground and slips came down from cliffs or steep slopes. Below here the river was for a time reduced to a trickle by blockages up toward Murchison and in the Maruia Valley. Fortunately those were breached gradually instead of bursting away suddenly and causing greater devastation. Reports that a nearby mountain known as the Old Man of Buller had been toppled turned out to be unfounded – the Old Man can still be seen, further up the gorge. However, hundreds of local people had their homes destroyed and lives devastated. Seventeen people were killed, most engulfed by landslides as far away as Seddonville on the West Coast. At Whale Creek Flat, just east of here, three children and a teacher escaped from their classroom just before boulders, tree debris and mud swept it away. Three men working in a river diversion tunnel through the neck of this peninsula also had a terrifying experience, but fortunately their exit was not blocked. Looking back later, people realised that booming noises heard during the days leading up to the quake had been forerunners to it, not blasting on the railway or farms as thought at the time. Two years later, in a highly populated area, the massive Hawkes Bay earthquake claimed two hundred and fifty six lives.

4. Leaving their wrecked homes behind them and carrying what they could, people from this part of the gorge sought refuge in safer, more open country near Murchison. 5. Numerous slips slowed refugees from outlying districts on their way to Murchison. With telephone lines down, they would be eager for news of family and friends elsewhere. 6. Deaths might well have topped twenty if the pupils, teacher and a visitor had not fled the Whale Flat School before it was struck by a landslide.

On the way back to the bridge we saw the cutest little miners house.

This time as we crossed the bridge we stopped to take in the scene, where the faultline is – beside the waterfall and the various flood heights.

ALL IN ALL AMAZING TO SEE FIRST HAND THE POWER OF WATER INCREDIBLE FLOOD HEIGHTS

|