PA Church

|

Port Arthur Convict Church, Her Bells, Some People and

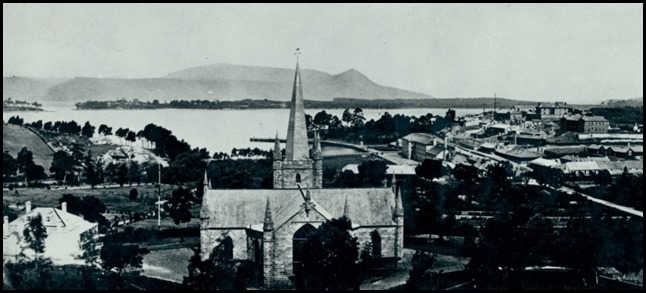

Some Other Bits and Bobs  The church at

Port Arthur seen from Scorpion Rock, overlooking the settlement

pre-1876. David Burn wrote in An Excursion to Port Arthur,

1842: The church at Port Arthur is a beautiful, spacious, hewn stone

edifice, cruciform in shape, with pinnacled tower and gables.... There is no

organ, but a choir has been selected from among the convicts, who chant the

psalms with considerable effect. The unnamed

church at Port Arthur stands on the hill looking down to Masons Cove and across

to the Isle of the Dead.

The foundation stone of the church was laid in 1836 by

Lieutenant Governor George Arthur on his final visit to the settlement. Probably

designed by the Deputy Commissariat Officer, Thomas Lempriere, and the convict

architect, Henry Laing. Although constructed by the convicts, much of the

stonework and panelled pew fronts were prepared by the boys from the Juvenile

Establishment at Point Puer.

The first service was held in 1837. The church was never

consecrated, partly to allow the use by several denominations and partly due to

disagreements between the various church authorities.

It had a wooden steeple which blew down during a gale in 1876.

In 1884 sparks from a fire lit to clean up around the parsonage caught the old

shingles on the church roof. Despite the efforts of the local residents the

church was irreparably damaged. The State Government took it over in 1913 and

since then the ruins have undergone periods of conservation. Restoration and

stabilisation was completed in 1976.

The church could accommodate a thousand worshippers, the

convicts entered by doors at either end of the building and were seated on

benches. The two hundred free people entered the church via the main entrance,

passing under a huge three tired pulpit to an area screened from the convicts

and sat in pews.    The church was presided over by Wesleyan ministers until 1843

when the Church of England’s Rev Durham was appointed, he happened to have a

hatred of Catholics. After his arrival the Roman Catholic prisoners refused to

attend services resulting in the appointment of Father Bond. Roman Catholics

sometimes used the church for services but in later years had a makeshift chapel

on the second floor of the Penitentiary or Prisoners’

Barracks.  The church – seen on the model of the

settlement in the Visitor Centre – held a dominant position. Government

House (white arrow) and the Parsonage (yellow arrow) were the buildings each

side, important positions. Completing the line-up were the rest of the houses on

Civil Officers’ Row.    Government House today. Now

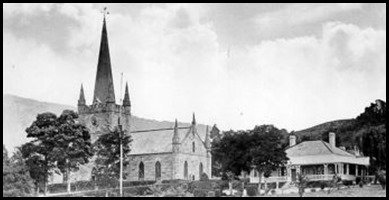

only ruins since the 1895 bushfires.   The Church and Government Cottage (seen to the right) in 1887 – once a

lovely cottage built in 1853, overlooking the Government Gardens, it never had

any permanent residents but was where important visitors to the settlement such

as the Comptroller of Convicts would stay. Prior to its construction those

visitors would have had to have lodged in the Commandant’s House. H. Hunter

wrote on the 15th of November 1872: Near the

church is Government Cottage, a very pretty little place. Everything about it is

in excellent order; the garden and ornamental grounds are well kept, and

altogether reflect much credit upon the person in charge. From its earliest

days the cottage was surrounded by oaks, elms, ash trees, roses and the

beautiful Government Gardens where the officers’ wives and children used to

walk. John Stephen Hampton was the first

Comptroller General to occupy Government Cottage. He was not a popular man among

colonial politicians and in 1855 the Select Committee into the Convict

Department found that he was engaged in corrupt practices, including employing

convict labour for personal profit. Hampton was not in the colony when required

to give evidence to the Committee; he was on sick leave and all of his furniture

in the cottage was sold off.   The view from Government Cottage over the

Government Gardens in 1873. Many of the features have been carefully

recreated, including the large rose arbour at the bottom of the path, as we saw

the gardens today. Thomas Lempriere wrote in 1839:

........its (the settlement of Port Arthur) first appearance is

pleasing and impresses on the mind an idea of cleanliness and

regularity.  The topiary plants, clipped to shape, created the framework for the garden, (seen to one

side). On either side of the intersecting paths the plantings were

orderly and symmetrical. This reflected the military background of the colonial

administrators and was in keeping with nineteenth century ideas that a person’s

environment influenced their character. Visitors to this garden would see nature

tamed and disciplined.

The Parsonage was

the northernmost building of the houses in Civil Officers’ Row adjacent to the

convict church. Construction of the house began in the early 1840’s without

permission from Hobart and was the first of five to be built.

It was the only two storey house built on the site and reflected

the senior status of the clergy. The first occupant was the Wesleyan missionary

Rev John Manton (1807-1864) in 1842. Manton's first appointment was

at Parramatta. Six months later he replaced Rev. William

Schofield in the penal

station at Macquarie Harbour, Van Diemen's Land, whence he sailed in January

1833 for the new penal settlement at Port Arthur to become its first chaplain.

At Sydney in April he married Anne Green from Spilsby, Lincolnshire.

In addition to the usual

clerical duties at Port Arthur, he organised and conducted schools for adult

convicts and instructed some seventy convict boys at Point Puer, later receiving

special thanks from Lieutenant-Governor (Sir) George

Arthur for his faithful

services. In 1834 he was transferred to Launceston where for three years he

conducted a most successful ministry. This was followed by short terms in other

settled parts of the colony. In 1841 Manton was reappointed to Port Arthur,

where he remained until the government, unsettled by the influence of Bishop

Francis

Nixon, decided to withdraw

Wesleyan chaplains from penal stations despite their long ministry of fourteen

years. He then became superintendent minister at Hobart Town, and later moved to

other centres. The Irish born

Reverend Edward Durham, his wife and six children and his family were the first

long term occupants and lived here for ten years from his appointment in 1843.

His time at Port Arthur was characterised by constant disputes with three

successive Commandants. Among Durham’s complaints was his dislike of Catholics

and in particular his disdain for Catholic chaplain, Father O’Halloran, whom he

called a ‘hot headed zealot, totally unfit to administer instruction to the

convicts. Commandant Booth disliked his

attitude and saw this as evidence that Durham was in fact, mad. But such

differing of opinion between Catholics and the church of Ireland was not

uncommon for the time. Letters from Durham to the Commandant that have survived

from the time, however, some reveal a reasonable man. He requested that the

convicts be allowed to attend prayers under shelter, a plea for humane treatment

that Booth denied. He reminded Booth that the chaplain should be responsible for

running the school and the library. A later inquiry proved him right. That same

inquiry, however, found that although he was hot headed and intolerant, Durham’s

effort to improve the convict’s moral condition was beyond all praise. One

former convict wrote that he had won the heart-felt respect of all those

unfortunate people with whom he had come into

contact. Durham also

frequently clashed with the settlement schoolmaster, John White. This dispute

led to an external investigation into Durham which found that he was

‘injudicious in some instances arising entirely from an overzealousness and

ignorance of his real position......... There is much of

his correspondence on the web, here are just a few examples:-

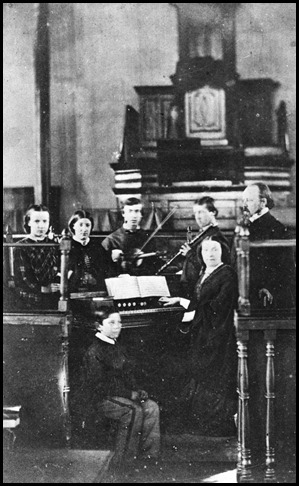

“I would suggest the advantage of the prisoners attending the church (instead of the yard) for morning prayers, when the Clergyman could give a short address which under God, would have a most salutory effect in restraining the men from rushing into crime, during the day.” The Commandant has fully explained to Mr. Durham that it is impracticable without serious infringement on time causing several unnecessary musters. “I would suggest the propriety of permitting all the prisoners to attend public worship on the Lord’s day, none to be confined in solitary cells during divine worship; also to allow the prisoners confined in solitary cells and those chained on to log, to attend the school for one hour each day for educational purposes, as they are debarred from all instruction; not even allowed a book, from the library or to attend the evening school.” No one would be more desirous than the Commandant and often have had it in contemplation but find it cannot be done without much risk. They are allowed one hour or near it each day in the school room. No book but the Bible is allowed to men under such circumstances. If books of amusement were permitted it would do away with the punishment. “I am very much surprised at the concluding part of this sentence "much risk." Surely no risk can be run in marching 14 men (mainly ironed, and every way unarmed) from the cells to the church; besides if there by any prospect of impressing the minds of these men and thus effecting a reformation we may reasonably expect it in the use of the means, God has appointed, bit…..” The Schoolmaster wrote: ………Last night because I ordered some of the men to their desks, who were walking about the school Mr. Durham asked me by what authority I ordered a man (a very bad character) of the name of Green to his seat. I told him I had done so in accordance with the regulations of the school and that I had strict orders from the Commandant on the subject. He immediately said, "I order you to appoint John O'Donnell (another bad character whom I had sent to his seat) to act as second Monitor at the 28 other O’Donell’s desk.” I replied that I should do so if such were the Commandant’s orders he then said “mind you see and do it.” Mr. Durham was very violent in his manner and shook his stick at me and said to the man whom I had ordered to his seat “come along with me” and he took him from the place I had ordered him to. ……………………. By the early 1850’s, the Durham’s had returned to Ireland and the Reverend’s health had deteriorated to the point he was committed to an asylum.  The Rev

George Eastman (seen here with his family) was the chaplain at Port

Arthur between 1855 and 1870. Before this he had been at the Female Factory at

Ross for several years. In 1845 Eastman had married Louisa McLeod, the couple

were to have ten children. His older boys were said to be a nuisance about the

settlement, often disrupting the smooth running of the farm and annoying the

convicts in charge of the animals. Eastman himself was said to be ‘much esteemed

by the Members of his Communion and by his brother Officers for his kindly,

genial and charitable disposal and was known as the Good Parson by the

prisoners. When they got their ticket of leave he always gave them some money to

help them on their way’ (Scripps, 1997 Civilian and religious precinct, p.16).

In April 1870 Eastman was sick in bed with a cold when he was called to attend

to a prisoner who was ill at an outstation. His cold developed into a chill and

two days later he died at the age of 48.

Rev Eastman was buried on the Isle

of the Dead on the 28th of April

1870. The Parsonage burnt down in the bushfires

of 1895. Annie Blackwood purchased the ruins and rebuilt it as her home and ran

post office for over forty years until the late 1970’s. The Parsonage gained a

reputation for being haunted during the 1870’s while the Reverend Hayward lived

here, it is thought because Reverend Eastman died in the upstairs

bedroom.

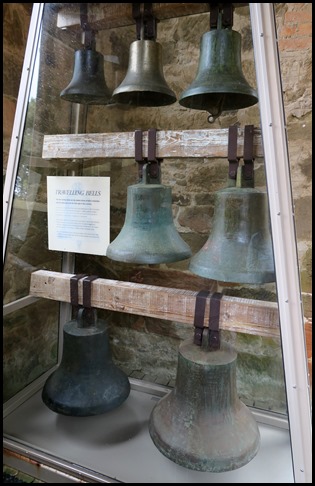

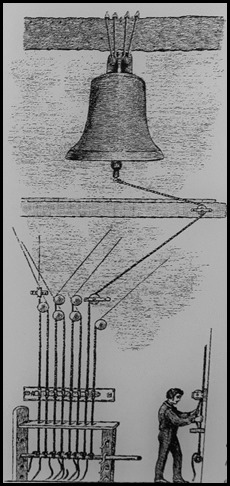

The Port Arthur Bells: Today there are seven bells hanging in the area that was once the Vestry of the Port Arthur Convict Church. These bells were cast at Port Arthur in 1847, making them the earliest known chime of bells cast in the country. They may also be the only chime pitched like this in Australia. They are part of an octave set, of which one is missing, and are pitched approximately in the key of G Major. I was aroused from my reverie by the sound of bells pealing lightly upon my ear...They chimed in so beautifully with the bright and peaceful scene around and seemed to float upon the air tinkling echoes from afar, that one almost fancied they were ringing in the sky. But this was not the case, they proceeded from the tower of the church, and in a few minutes I found myself within its walls awaiting the commencement of morning service. (G. Gruncell c.1874 - Reminiscences of Port Arthur and Tasman's Peninsula) Casting the bells: Bell casting requires knowledge of music, metallurgy and mathematics. The name of the Port Arthur bell founder is so far unknown, but he was clearly a man of considerable skill and experience. Presumably he was one of the convicts working in the penal settlement’s blacksmith shop and foundry, where a wide range of high quality metal items were made for use on the settlement, for government use and for export. The bells have been analysed to see what metals the bell founder used. No two bells are the same. Five are of bell metal, varying in quality from good to poor; two are of soft gun metal, which is not really suitable for bells. Only one bell is considered to be cast from correct bell metal. Presumably the bell founder had to work with whatever was available at the time. The moulds were constructed in two parts, a ‘core’ and a ‘cope’. The core which shaped the inside of the bell was made by constructing a curved armature or skeleton and covering it with a loam (usually consisting of sand, clay, possibly manure all held together with wool or chopped straw). The cope (the mould for the exterior) was then lowered over the core; the two moulds were fired and fixed to a base plate. The gap between the two components of the mould was the exact space required for the molten metal to be poured in, taking into account that the thickness and diameter of the resulting cast metal is what gives a bell its unique sound.

A ‘chime’ not a ‘peal’: Port Arthur’s bells are a ‘chime’, not a peal. A chime is the technical name for a set of bells (less than 23), which are rigidly suspended and played by pulling a rope attached to a metal clapper so that it strikes inside the rim of the bell. Today, several of Port Arthur’s bells display an abraded and discoloured band where the clapper struck them. A peal is the name given to a specific type of performance of bell ringing. The precise definition of a peal has changed considerably over the years and historically it was common that a set of bells regardless of their technical situation was called a peal. The church – a very pretty structure, having a steeple a hundred feet high, and a peal of eight very sweet bells, which are used to ring solemn peals on Sabbath days, and are in requisition occasionally when a wedding or a christening is performed. (The Mercury, Hobart, 23rd of March 1870). Port Arthur’s chime of eight bells was played like a musical instrument by a single convict. Unlike swinging bells, common to many churches, this chime was secured to four large timber beams in the church tower, Each bell was struck or ‘clocked’ by a metal ‘clapper’ pulled against one inside surface of the bell. Chiming timing: Each morning the bells were rung to signal time to go to work; they rang twice a day for prayers, and possibly also to tell the men to down tools in the evening. They chimed for both the Protestant and Catholic services. The slow tolling of a single bell accompanied burial parties from the church to the jetty, en route to the settlement cemetery, the Isle of the Dead. With two of the seven bells unplayable and one missing, the chiming bells you can hear on site today are a recreation of the octave using the five playable bells as well as digital sound reproduction technology. Well-travelled bells: In 1877, when the settlement closed, the eight bells were sent to the New Norfolk Insane Asylum, an institution with which Port Arthur had strong links. In 1897 they were lent to the New Norfolk Municipal Council and hung in the St Mathew’s church tower. Unfortunately, this tower was structurally deficient, and in 1906 the bells were split up and distributed to churches and other institutions in the Upper Derwent valley, including the New Norfolk Convent, the Fire Brigade (where it was used for fire warnings), St Mathew’s Church, Lachlan Park Hospital, and other churches at Bushy Park, Molesworth, Lachlan and either Black Hills or Glen Fern. At some point one of the bells went missing; it has still not been located. In 1928 the largest bell was returned to Port Arthur. In 1995 New Norfolk Council agreed to return the six remaining bells. We have our suspicions as to the hiding place of the lost bell – a certain tortoise in Cornwall may....in fact.... be using it as a summer shelter.................

ALL IN ALL FASCINATING REMARKABLE |