Kirstenbosch Garden - Part 1

Beez Neez now Chy Whella

Big Bear and Pepe Millard

Mon 13 Jan 2020 23:17

|

Kirstenbosch National Botanical Garden – Part

One

We had Rod and Mary’s car for one final

day and there was only really one place to go before returning the steed on the

morrow. Kirstenbosch - flagship of the South African National Biodiversity

Institute – was established in 1913 to conserve and promote the indigenous flora

of southern Africa. Kirstenbosch is internationally acclaimed as one of the

great botanical gardens of the world. Situated on the eastern slope’s of Cape

Town’s magnificent Table Mountain, the estate, covering 528 hectares, includes a

cultivated Garden and a nature reserve. The developed garden (36 ha) displays

collections od southern African plants including many rare and endangered

species. Theme gardens include the Fynbos Garden, Forest Braille Trail and

Fragrance Garden, Useful Plants Garden and Water-wise Garden. The Botanical

Society Conservatory is a desert house that displays the succulent treasures of

southern Africa, as well as collections of bulbs, fern and cliff

plants.

Even in prehistoric times, people were

living here. Stone age hand axes were found near the spring in the Dell, and

this land formed part of the territory of two Khoikhoi clans. Jan van Riebeeck,

commander of the Dutch East India Company, surveyed the forests here in October

1652, and appointed the first forester Leendert Cornelissen, in 1657, to protect

the forests and to supply the Company with timber.

Van Riebeeck planted the hedge of Wild

Almond Trees in 1660 to mark the boundary to the settlement. He also established

many fruit trees, wheat lands, and trees like oaks and chestnuts on his own farm

called “Boscheuwel” which is adjacent to Kirstenbosch, and planted ten thousand

Muscat d’Alexandrie grapevines on the slopes of Wynberg.

During the 1700s the land was owned

and used for timber by the Dutch East India Company. After the 2nd British

Occupation (1806) the land was bought by the Colonial Secretary Henry Alexander

and his deputy, Col. Christopher Bird, who built a brick bath at the spring in

the Dell.

During the 1800s Kirstenbosch was a

farm, owned by the Cloete family. Very good wine was produced by their

vineyards. The last private owner of the land was Cecil John Rhodes, who bought

it in 1895 for 9000 pounds to protect the eastern slopes of Table Mountain from

urban development. He planted the avenue of camphor

trees.

Kirstenbosch was left to the nation in

1902 when Rhodes died, and on the 1st of July 1913 it became a botanical garden

dedicated to the cultivation and study of indigenous plants of South Africa.

Prof. Harold Pearson, a Cambridge botany graduate, was appointed the first

Director and established the Cycad collection. Mr. J.W. Mathews, who trained at

the Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew, was the first Curator, and he was responsible

for the layout of much of the garden, including the Dell, Koppie, Cycads, Main

Lawn, Vygie Beds and the Mathews Rockery.

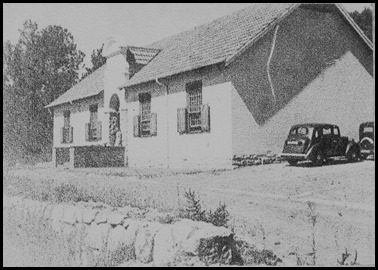

At the top of the avenue of camphor trees

(to our left) we came upon a building. The Herbarium of the National Botanic Gardens in 1942. The

building was built in 1924 and housed the Bolus Herbarium until 1938. The

Herbarium was named after Prof Compton in 1954. The building was enlarged by the

addition of two wings in 1957-58. The Compton Herbarium moved to its current

location in the Kirstenbosch Research Centre in 1996. Its old building now

houses the Garden Office.

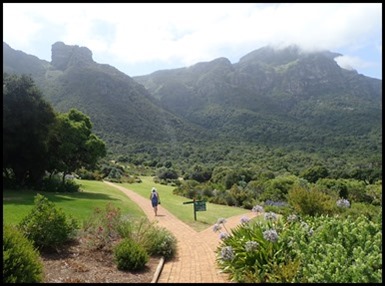

We followed the path to take in the eastern slopes of Table Mountain, sit awhile in front of

hundreds of agapanthus, take in the

view......

...........and appreciate the sheer size of the garden....

........ with Cape

Town below us.

A gang of little

chaps came to scruff at our feet.

One view was not

quite in keeping, even Table Mountain chose to put on a

blindfold......

Two types of sunbird, the Lesser

Double-collared and the Orange-breasted visit the garden. We watched this drab coloured female (Orange-breasted) about her business.

Sunbirds drink the nectar from flowers using a tongues especially adapted

for this. They are long, with a brush tip and can fold into a tube so that the

bird can suck the nectar up, just like we do when we drink through a drinking

straw.

Sunbirds and

hummingbirds certainly look alike. They are both small, brightly coloured and

feed on nectar, but they are not related. Hummingbirds are related to swifts and

occur in the Americas, while sunbirds are related to sparrows and occur in

Africa, Asia and Australia. They look alike because they have adapted to the

same kind of conditions and food sources. They are an example of convergent

evolution.

Where you see tubular-flowered ericas

you will see sunbirds: Sunbirds are the pollinators of at least 70 kinds of

ericas. These ericas have tubular flowers that are brightly coloured or

conspicuous, and have no scent. The flowers and the birds have evolved together.

The shape of the flower, its bright colour, how they are presented on the stems,

are designed to attract the sunbirds. The sunbird perches on the sturdy stems,

and as it probes with its beak into the flower to reach the nectar at the base

of the flower, its beak touches anthers and pollen gets dusted on its beak. The

burs then flies to another flower, taking the pollen with it, transferring some

to that flower and picking up some more. In this way, the flower gets pollinated

and produces seeds. The plant rewards the sunbird for doing this service by

producing energy-rich nectar. This is an example of co-evolution. I need to

get out more but cannot help being addicted to information

boards....

.

.

‘Things along the

way’.

A female sunbird

scruffing in a white agapanthus.

The Silver

Tree.

The Silver Tree

(Leucadendron argenteum) is unique to Table Mountain. These giant

silver protea with their silky, shimmering leaves grow wild on the slopes above

Kirstenbosch. In nature they are found only on the cool, east and south-facing

slopes on the Table Mountain chain. In the 1700s and 1800s silver trees were

widely planted for firewood and it is thought that the silver trees that grow in

Paarl, Somerset West and Stellenbosch are not natural but were planted in those

days and have naturalised. The silver tree is classified as Rare, because it has

a small wild population and a small distribution range. Its Red List status is

Endangered and it is estimated that this species could go extinct in the wild in

the next 50 years if the remaining wild population are not properly cared for.

It has a reputation for being very difficult to grow, mainly because it is

susceptible to the phytophthora root rot fungus. It also dislikes wet, soggy,

rich soils and humid air. But if you have a cool but sunny, well-drained slop

where their roots will be as undisturbed as possible, they grow fast and well,

and can thrive far from home. This is a fast growing ornamental tree 7 – 10

metres tall, with large light reflecting silver grey leaves, spring flowering

(Sept), wind tolerant, foliage useful for flower arrangements and my

favourite tree protea. The trees can be either male or female. Male and

female flowers are borne on separate plants. The term for this is dioecious

(die-ee-shuss). They are easy to tell apart. The female tree will have large

woody cones on older stems – silver while young. The male has none. The female

flower is a silver ball with a few hairy yellowish flowers dotted on it. The

male flower head is made up of many yellow and silver flowers packed into a

rounded ball.

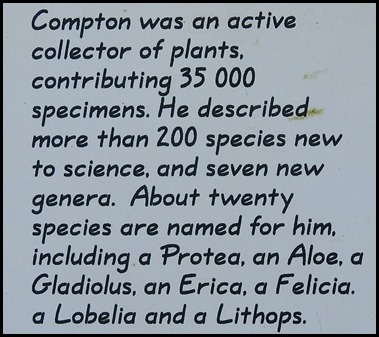

Robert Harold Compton. 6th of August 1886 – 11th of

July 1979. Director of Kirstenbosch and the National Botanic Gardens of South

Africa 1919 – 1953. Prof Compton’s

legacy.

The Science behind the Garden: From its inception,

Kirstenbosch intended to be more than just a pleasant place for people to visit

and enjoy the beauty of South Africa’s plant life. It was also to be a place of

scientific study. Botanical Science, the study of plants, and Systematic Botany,

the naming, description and study of the relationships between the plants and

the construction of classification systems to reflect their relationships,

underpins the botanic garden. The Garden enables the botanist to study live

plants, and their life sequence. The Herbarium, where plant specimens are dried,

filed and preserved, allows for a permanent record, reference and future

comparison of plants. It is a vital part of the Garden, the centre of botanical

research and it identifies the incoming plant material. In 1939 Professor

Compton founded the Gardens Herbarium, starting with just 18 cabinets. Today the

Compton Herbarium is the second largest herbarium in southern Africa and houses

approximately 750,000 specimens, providing an archival record of 12,000

species.

After taking in

some more plants we went in search of Harold

Pearson’s grave.

The grave, up the slope Bear sat

whilst I took in the information boards.

Harold Pearson (right) and two

of his friends in Kirstenbosch c.1914. Henry

Harold Welch Pearson (28th of January 1870 – 3rd of November 1916

(looked it up and he died of pneumonia)/ Professor of Botany at the

South African College 1903 – 1916. Director of Kirstenbosch and the National

Botanic Gardens of South Africa 1913 – 1916.

The memorial

plaque reads: Henry Harold Welch Pearson MA ScD PR FLS. Professor of Botany

SA College. First Director of these Gardens. Died 3rd Nov 1916. Aged 46. If ye

seek his Monument look around.

This is a fitting resting place for

Professor Harold Pearson, whose vision led to the creation of Kirstenbosch

National Botanical Garden. Pearson had tremendous drive and enthusiasm, and made

a lasting contribution to South African Botany. As the first Director of

Kirstenbosch, he initiated the transformation of a neglected farm into a world

famous botanical garden. As Professor of Botany at the South African College

(now the University of Cape Town), he revitalised research in the department,

and established an important link between the university and the

Garden.

Pearson had a special interest in

Gymnosperms (cone bearing plants), such as Welwitschia, cycads and conifers. His most important work was done on

Welwitschia and Gnetum and he undertook several difficult journeys to Namibia

and Angola to collect specimens. He also researched cycads and collected 300

Encephalartos plants which are the foundation of the Kirstenbosch collection and

many of his plants are still alive today. The North African Cedar (Cedrus

atlantica var glauca) above his grave was a gift to Pearson from his colleagues

at the Royal Botanical Gardens, Kew, in England. Seeds arrived in August 1916,

and the sapling was planted here in 1919.

Pearson arranged his professorial

duties so that he could devote Wednesday, Saturday and Sunday to the Garden. His

evenings were spent walking around the Garden inspecting work and arranging

various matters with the Curator and Ranger, and attending to Garden

correspondence, writing up his research notes and reading.

More

plants along the way.

We stopped at a sprawling Wild Almond Tree (see small boy climbing). The Wild Almond (Brabejum stellatifolium) is a member of the

Protea Family (Proteaceae). Its closest living relative is the Australian

Macadamia Tree. It points back to a time, millions of years ago, when Australia

and Africa were part of an ancient continent called Gondwana. When Gondwana

broke up in pieces drifted apart about 130 million years ago the Protea Family

got split up. Brabejum is the only survivor of its branch of the family tree on

the African piece of Gondwana. The almond-shaped fruits are densely covered with

rusty-brown velvety hairs. Inside the fruit is a single seed.

Wild Almond

fruits were harvested and eaten by the Khoikhoi. In 1660 they petitioned the

Company for access to some Wild Almond Trees that now fell inside the borders of

the settlement. The Company did not grant this petition. Instead they used the

fruit trees to plant Van Riebeeck’s Hedge. For many, this hedge marks the first

step on the road to Apartheid and symbolises how white South Africa cut itself

off from the rest of Africa, dispossessed the indigenous people and kept the

best of the resources for itself. Our challenge in South Africa today is to

dismantle the barriers erected in the past, share the resources equally and

build a home for all.

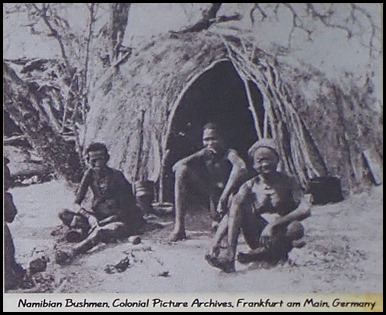

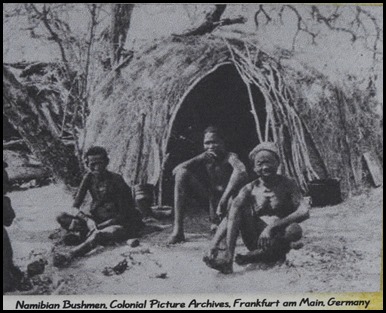

The First People of the Cape: Africa

is the cradle of humankind, people have been living here for millennia. The

earliest evidence of modern humans in the Western Cape is about 130,000 years

ago, and on the Cape Peninsula about 30,000 years old. Until a few thousand

years ago all the people of the Western Cape lived by hunting animals and

gathering plant foods. About 2,000 years ago some of the people started keeping

domestic sheep, cattle and dogs, and making pottery. The hunter-gatherer people

are known as the San while the herders are known as the Khoikhoi, but they were

connected and related to each other. The arrival of European colonists caused

great changes to the old ways of life, many of the people lost their lands and

moved away, some joined up with other groups to survive, or they joined the

colony and became part of colonial society. Today, we recognise all the

indigenous people of the Cape as Khoisan people.

Hunting and gathering, an ancient way

of life: For thousands of years hunter-gatherers lived successfully all over

southern Africa, from the driest to the wettest regions. They lived a largely

nomadic lifestyle, following seasonal supplies of food and water. They took only

what they needed and made sure that there would be enough left for next year.

They did not build houses out of stone or brick but built temporary shelters

using plants or used natural rock shelters. They were skilled hunters with a bow

and arrow. They had extensive knowledge of plants, gathering them for food,

medicine, poison for their arrows, cosmetics and to make mats, string and nets.

They made their clothes and bags out of animal skins and beads and ornaments out

of tortoiseshell, ostrich shell, seashells, ivory, wood and bone. They were

talented artists, using ochre and mineral pigments on rock. They had complex

religious beliefs and practices and were brilliant

storytellers.

The San saw themselves as sharing the

world with the animals and believed that there was a relationship of trust

between the hunter and the hunted. Only a hunter that showed humility, and

respect for the animal they hunted would be successful in catching it. This

respect carried over to people – all members of a group were equal, all food and

goods were shared equally, and everyone had a say when decisions had to be made,

or disputes dealt with.

Imagine no need for Mrs

Pankhurst........

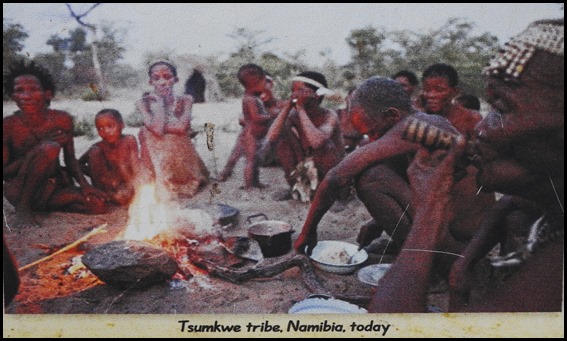

Where are the San today?: The San have

not remained frozen in time but have adapted, changed and developed like all

other people. There are still a few communities in the Kalahari that maintain a

hunter-gatherer lifestyle but many San people were absorbed into the general

population of modern South Africa where they have contributed to South African

culture with their art, imagery, pottery, fables and history, and their

knowledge and experience of indigenous plants and animals. During the colonial

and Apartheid eras, indigenous people and their culture were overtaken, pushed

aside and made to feel inferior. Today, people are proud of their indigenous

Khoisan heritage, they are raising awareness of what it means to be Khoisan,

exploring Khoisan identity and promoting growth and development of Khoisan

culture.

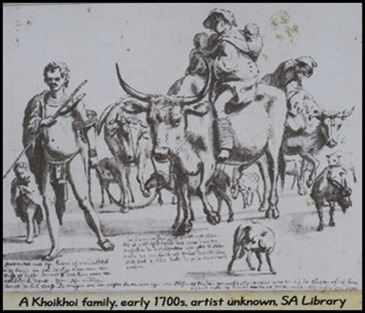

The Cape

Herders: When European ships first rounded the Cape in the late 1400s

they were pleased to see Khoikhoi people on the shore because they had sheep and

cattle and the sailors were keen to trade with them for fresh meat. The first

recorded livestock trade between them took place at Mossel Bay on the 2nd of

December 1497, and for the next 155 years until the arrival of van Riebeeck,

some Khoikhoi clans traded their livestock for metals with passing

ships.

Khoikhoi clans each had a territory

and they owned and controlled the resources in their territory. Neighbours

shared with each other, on condition that permission was asked and granted. Two

clans lived on the Peninsula – the Gorachouqua and Goringhaiqua. They grazed

their livestock in Table Valley in early summer, travelled to the Hout Bay area

during midsummer and then crossed the Cape Flats to their winter grazing in the

Boland.

Life on the move: Because the

vegetation in the Cape has a low nutritional value and other parts of the

country are very dry, the Khoikhoi followed a nomadic life, moving regularly to

take advantage of seasonally available grazing. They built dome-shaped

mat-covered huts which could easily be dismantled, the mats rolled up and loaded

on the cattle and the hut rebuilt at the new camp. These huts were also

well-designed to withstand strong winds. Their distinctive pottery was made to

be easily transported.

Cattle were owned by individual people

and were a sign of wealth. A father passed his stock on to his sons and

daughters. They used the cattle mainly for milk and transport – they were

slaughtered only on ceremonial occasions. Men and boys looked after the cattle,

milked the cows and killed stock, went to war, hunted and made the weapons.

Women and girls looked after the children, fetched wood, gathered the plants

needed to at or use for medicine, cosmetics or to make things like mats and

string and prepared the food.

What’s in a name?: Jan van Riebeeck

referred to the Khoikhoi as Quena, or Khoina, which is the name used to refer to

themselves and it means ‘the people’. Khoi meaning one person and Khoina many.

In other regions Khoikhoi was the plural of Khoi. In modern Nama the spelling is

Khoekhoe.

The name Hottentot was used by

European travellers and colonists to refer to the Khoikhoi, possibly because the

Khoikhoi language had many click sounds that were very unfamiliar to the

Europeans and their name was trying to imitate it. Today this name is regarded

as insulting.

More ‘things’,

now off in search of Mathews Rockery.

CONTINUED |