Chocolate Part

Two

Production:

Roughly two-thirds of the entire world's

cocoa is produced in Western Africa and according to the World Cocoa Foundation,

some 50 million people around the world depend on cocoa as a source of

livelihood. The industry is dominated by three chocolate makers, Barry

Callebaut, Cargill and Archer Daniels Midland Company (ADM). In

the UK, most chocolatiers purchase their chocolate from them, to melt, mould and

package to their own design. Despite some disagreement in the EU about the

definition, chocolate is any product made primarily of cocoa solids and cocoa

fat. The

different flavors of chocolate can be obtained by varying the time and

temperature when roasting the beans, by adjusting the relative quantities of the

cocoa solids and cocoa fat, and by adding non-chocolate

ingredients.

Production costs can be decreased by

reducing cocoa solid content or by substituting cocoa butter with a

non-cocoa fat. Cocoa growers object to allowing the resulting food to be called

"chocolate", due to the risk of lower demand for their crops.

There are two main jobs associated with

creating chocolate candy, chocolate makers and chocolatiers. Chocolate makers

use harvested cacao beans and other ingredients to produce couverture

chocolate. Chocolatiers use the finished couverture

to make chocolate candies (bars, truffles, etc.).

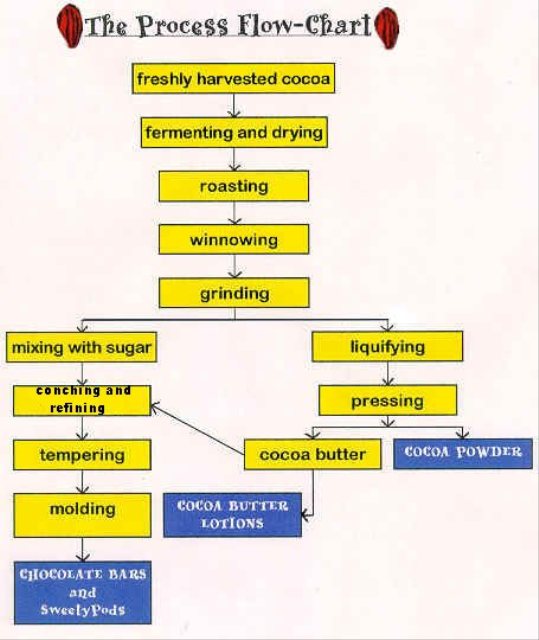

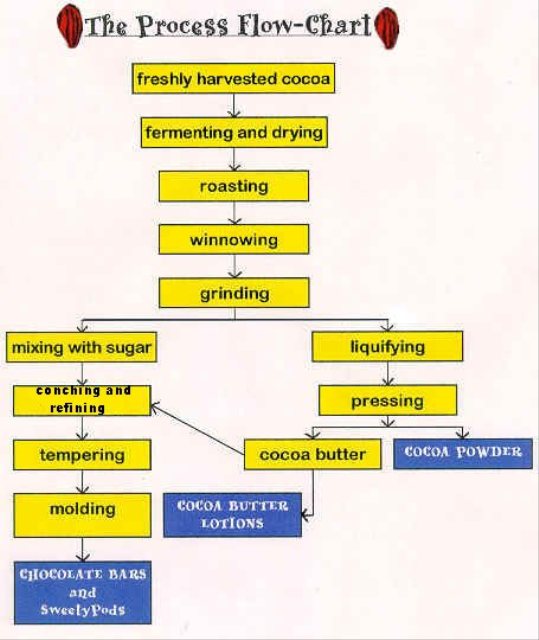

Processing:

Cocoa pods are

harvested by cutting the pods from the tree using a machete, or by

knocking them off the tree using a stick. The beans with their surrounding pulp

are removed from the pods and placed in piles or bins to ferment. The

fermentation process is what gives the beans their familiar chocolate taste. It

is important to harvest the pods when they are fully ripe because if the pod is

unripe, the beans will have a low cocoa butter content, or there will be

insufficient sugars in the white pulp for fermentation, resulting in a weak

flavor. After fermentation, the beans must be quickly dried to prevent mold

growth. Climate and weather permitting, this is done by spreading the beans out

in the sun from 5 to 7 days.

The dried beans are then transported to a

chocolate manufacturing facility. The beans are cleaned, roasted, and

graded. Next the shells are removed to extract the nib. Finally, the nibs are

ground and liquefied, resulting in pure chocolate in fluid form: chocolate

liquor. The liquor

can be further processed into two components: cocoa solids and cocoa

butter.

Blending:

Chocolate Melanger

Chocolate liquor is blended with the cocoa

butter in varying quantities to make different types of chocolate or

couvertures. The basic blends of ingredients for the various types of chocolate

(in order of highest quantity of cocoa liquor first), are as

follows:

Dark chocolate: sugar,

cocoa butter, cocoa liquor, and (sometimes) vanilla

Milk chocolate: sugar,

cocoa butter, cocoa liquor, milk or milk powder, and vanilla

White chocolate: sugar,

cocoa butter, milk or milk powder, and vanilla

Usually, an emulsifying agent such as soy

lecithin is added, though a few manufacturers

prefer to exclude this ingredient for purity reasons and to remain

GMO free,

sometimes at the cost of a perfectly smooth texture. Some manufacturers are now

using PGPR, an artificial emulsifier derived from

castor oil that allows them to reduce the amount of cocoa butter while

maintaining the same mouthfeel.

The texture is also heavily influenced by

processing, specifically conching (see below). The more expensive chocolate

tends to be processed longer and thus have a smoother texture and "feel" on the

tongue, regardless of whether emulsifying agents are

added.

Different manufacturers develop their own

"signature" blends based on the above formulas, but varying proportions of the

different constituents are used.

The finest, plain dark chocolate

couvertures contain at least 70% cocoa (both solids and butter), whereas milk

chocolate usually contains up to 50%. High-quality white chocolate couvertures

contain only about 33% cocoa.

Producers of high quality, small batch

chocolate argue that mass production produces bad quality

chocolate. Some

mass-produced chocolate contains much less cocoa (as low as 7% in many cases)

and fats other than cocoa butter. Vegetable oils and artificial

vanilla flavour are

often used in cheaper chocolate to mask poorly fermented and/or roasted

beans.

In 2007, the Chocolate Manufacturers

Association in the United States, whose members include Hershey, Nestle

and

ADM,

lobbied the Food

and Drug Administration to change the legal definition of

chocolate to let them substitute partially hydrogenated vegetable

oils for cocoa

butter in addition to using artificial sweeteners and milk

substitutes. Currently,

the US FDA does

not allow a product to be referred to as "chocolate" if the product contains any

of these ingredients.

Conching:

The penultimate process is called conching.

A conche is a container filled with metal beads, which act as grinders. The

refined and blended chocolate mass is kept in a liquid state by frictional heat.

Chocolate prior to conching has an uneven and gritty texture. The conching

process produces cocoa and sugar particles smaller than the tongue can detect,

hence the smooth feel in the mouth. The length of the conching process

determines the final smoothness and quality of the chocolate. High-quality

chocolate is conched for about 72 hours, lesser grades about four to six hours.

After the process is complete, the chocolate mass is stored in tanks heated to

approximately 45–50 °C (113–122 °F) until final processing.

Tempering

The final process is called

tempering. Uncontrolled

crystallization of cocoa butter typically results in crystals of varying size,

some or all large enough to be clearly seen with the naked eye. This causes the

surface of the chocolate to appear mottled and matte, and causes the chocolate

to crumble rather than snap when broken. The uniform sheen and crisp bite of

properly processed chocolate are the result of consistently small cocoa butter

crystals produced by the tempering process.

The fats in cocoa butter can crystallize in six different

forms (polymorphous crystallization). The primary purpose of tempering is to assure that only the

best form is present. The six different crystal forms have:

|

Crystal |

Temperature |

Notes |

|

I |

17 °C (63 °F) |

Soft, crumbly, melts

too easily. |

|

II |

21 °C (70 °F) |

Soft, crumbly, melts

too easily. |

|

III |

26 °C (78 °F) |

Firm, poor snap,

melts too easily. |

|

IV |

28 °C (82 °F) |

Firm, good snap,

melts too easily. |

|

V |

34 °C (94 °F) |

Glossy, firm, best

snap, melts near body temperature (37 °C). |

|

VI |

36 °C (97 °F) |

Hard, takes weeks to

form. |

Making chocolate

considered "good" is about forming as many type V crystals as possible. This

provides the best appearance and texture and creates the most stable crystals so

the texture and appearance will not degrade over time. To accomplish this, the

temperature is carefully manipulated during the

crystallization.

Generally, the chocolate is

first heated to 45 °C (115 °F) to melt all six forms of

crystals. Next, the chocolate is cooled to about 27 °C (80 °F), which will

allow crystal types IV and V to form. At this temperature, the chocolate is

agitated to create many small crystal "seeds" which will serve as nuclei to

create small crystals in the chocolate. The chocolate is then heated to about 31

°C (88 °F) to eliminate any type IV crystals, leaving just type V. After this

point, any excessive heating of the chocolate will destroy the temper and this

process will have to be repeated. However, there are other methods of chocolate

tempering used. The most common variant is introducing already tempered, solid

"seed" chocolate. The temper of chocolate can be measured with a chocolate

temper meter to ensure accuracy and consistency. A sample cup is filled with the

chocolate and placed in the unit which then displays or prints the

results.

Two classic ways of

manually tempering chocolate are:

Working the molten chocolate on a heat-absorbing surface, such as a

stone slab, until thickening indicates the presence of sufficient crystal

"seeds"; the chocolate is then gently warmed to working temperature.

Stirring solid chocolate into molten chocolate to "inoculate" the

liquid chocolate with crystals (this method uses the already formed crystal of

the solid chocolate to "seed" the molten

chocolate).

Chocolate tempering

machines (or temperers) with computer controls can be used for producing

consistently tempered chocolate, particularly for large volume

applications.

Storage:

Chocolate is very

sensitive to temperature and humidity. Ideal storage temperatures are between 15

and 17 °C (59 to 63 °F), with a relative humidity of less than 50%. Chocolate is

generally stored away from other foods as it can absorb different aromas.

Ideally, chocolates are packed or wrapped, and placed in proper storage with the

correct humidity and temperature. Additionally chocolate is frequently stored in

a dark place or protected from light by wrapping paper. Various types of

"blooming" effects can occur if chocolate is stored or served improperly. If

refrigerated or frozen without containment, chocolate can absorb enough moisture

to cause a whitish discoloration, the result of fat or sugar crystals rising to

the surface. Moving chocolate from one temperature extreme to another, such as

from a refrigerator on a hot day, can result in an oily texture. Although

visually unappealing, chocolate suffering from bloom is perfectly safe for

consumption.

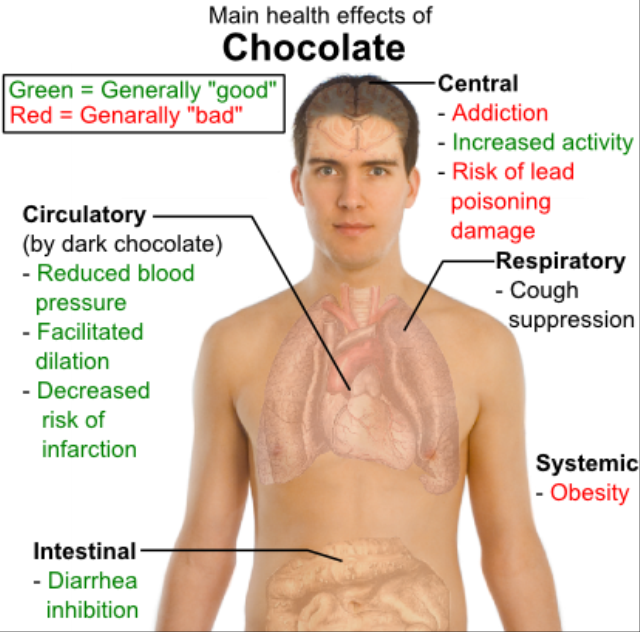

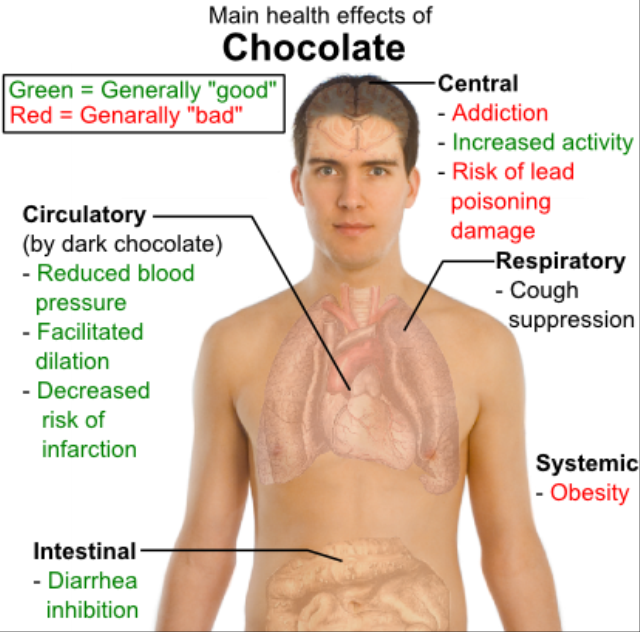

I am not even

"going there" on this picture

Chocolate

was introduced in to Europe by the Spaniards and became a popular beverage by

the mid 1600's. They also introduced the cacao tree into the West Indies and the

Philippines.

The

cacao plant was first given its botanical name by Swedish natural scientist

Carolus Linnaeus in his original classification of the plant kingdom, who called

it Theobroma ("food of the gods") cacao.

Whatever

- I like the very bitter dark stuff. I like Cadbury's Fruit and Nut best

NO ARGUING THERE THEN

ALL IN ALL THE WORLD WOULD BE A SADDER PLACE WITHOUT IT

-

VERY, VERY TASTY.