CM Night Tour

|

Cradle Mountain Night Tour to See the

Locals

We had been told by so many people

all over Tasmania to go on the night tour at Cradle Mountain. A very trusted elderly lady [two

months from retirement] picked us up at twenty thirty and our friendly driver

took us to pick a up a final passenger bringing our group to seven. Unsure what

we would get to see as last night was thin – “just a few wombats and wallabies.”

First though, we were off to Devils@Cradle, just down the road from our camp to

be told a bit about them and watch a few being fed – we hoped they shout and

scream at each other. A few minutes later we were welcomed by Tracy, our guide

who took us out onto the viewing gallery.

We soon saw our

first devil of the evening, just scruffing

about.

Another approaches but lays down submissively, our original

goes closer and snarls a bit.

Efforts in the late 1800’s to eradicate Tasmanian devils, which farmers erroneously believed were killing livestock (although they were known to take poultry on occasion), were nearly successful. In 1941, the government made devils a protected species, and over the years their numbers grew steadily, until Schwann cells tumours affecting the mouth and face became widespread.  Devil

Facts:-

Jaw Power: A Tasmanian devil

‘pound for pound’ has a jaw strength as powerful as any animal. It has evolved

to become a specialised scavenger within the Tasmanian landscape and this

strength enables these animals to efficiently devour native carcasses, including

the bones. And all the fur, which is thought to act like a fur ball

enabling the devil to cough up anything likely to block ‘the works’. They also

have incredibly white teeth.

Solitary/Social:

Typically a solitary animal, Tasmanian devils will roam their range in search of

food. However it is often in search of food that they become somewhat social,

whilst competing for their share of food it is not uncommon for several animals

to display behaviour over a carcass.

Gait/Endurance:

The devil runs with what appears to be a quite awkward movement, almost like a

rocking horse motion. Whist generally quite slow moving it is an efficient

motion which allows for great endurance and therefore the ability to cover long

distances in search of food.

Behaviour: The

largest of the carnivorous marsupial family, the Tasmanian devil has a

reputation as a nasty and aggressive animal however, it is typically a shy and

secretive animal. The range of growls, grunts and screams they display are often

misunderstood as aggression, rather than simply communication.

Body Markings:

From the moment joey Tasmanian devils develop fur they possess individual white

body markings, generally confined to the chest, shoulders and rump almost like a

finger print. Whilst a small percentage of individuals remain totally black this

is considered relatively rare.

During our short time here we saw a

tiny bit of white on a chaps chest, great splodges on a back and none at all –

about 16% of the population. Dare we say – they almost look cute. Their eyesight isn’t up to

much, they have a keen sense of smell and although

nocturnal they like to sunbathe during the day.

Tragically, though, a catastrophic illness discovered in the mid-1990’s has killed tens of thousands of Tasmanian devils. Called devil facial tumour disease (DFTD), this rapidly spreading condition is a rare contagious cancer that causes large lumps to form around the animal's mouth and head, making it hard for it to eat. The animal eventually starves to death. In 2008 they were declared endangered, their numbers decimated by

being bitten by a carrier devil. The experts believe this cancer spread

from just one female on the west coast of Australia – so how did it spread here

??? Man interfering yet again ??? No one knows for sure. It is hoped that a

vaccine will soon be available.

Next, we moved beside the pen that was to have a lump of meat staked down. There was a female [average weight six kilograms] and two males [eight kilograms] in this large enclosure. We met William who was very good at running the other two off from what he clearly saw as his supper. On average, devils eat about 15% of their body weight each day, although they can eat up to 40% of their body weight in thirty minutes if the opportunity arises. This means they can become very heavy and lethargic after a large meal; in this state they tend to waddle away slowly and lie down, becoming easy to approach. This has led to a belief that such eating habits became possible due to the lack of a predator to attack such bloated individuals. They like to eat their favourite bits - the internal organs, first. William polished the soft bits off in quick order then we heard as he crunched his way easily through the ribs. In the wild if a devil comes across a big, dead kangaroo, he will choose to eat the back leg muscle last as this proves to be tough going. Mothers give birth after about three weeks of pregnancy to twenty to thirty very tiny young. These raisin-size babies crawl up the mother's fur and into her pouch. However, the mother has only four nipples, so only a handful of babies survive. Infants emerge after about four months and are generally weaned by the sixth month and on their own by the eighth.

From the website: Devils@Cradle is a unique Tasmanian conservation facility focusing

on Tasmania's three carnivorous marsupials, whilst concentrating primarily on

the Tasmanian devil but including both the Eastern and Spotted - tail

Quoll.

The tourism side of the business allows visitors to view these animals from the comfort of the Visitors Centre or wander through the sanctuary on a personalised guided tour which ensures a close up encounter with a Tasmanian devil. One of our keepers will give you an accurate understanding of their lifecycle and the current threats that confront them such as Devil Facial Tumour Disease. We consider this aspect of the business a valuable tool in the education of the general public and an important part of our Conservation Program. The sanctuaries Tasmanian Devil population forms part of the nation-wide Captive Breeding Program (CBP) called the 'Insurance Population'. This CBP is managed by the Zoological and Aquariums Association (ZAA) in coordination with the Tasmanian Governments 'Save the Tasmanian Devil Program' (STTDP) and is vital to ensure the genetic diversity held within Australian Institutions and the future of the species. Similarly the sanctuaries Quoll CBP for both the Eastern and Spotted-tail is managed within Tasmania between associated institutions with coordinated support from the State Government Agency DPIPWE. Our Field Monitoring Program (FMP) collects data on all these species within the wilderness of Cradle Mountain through the use of remote cameras, road kill surveys, spotlight surveys and liaising with the local community and visitors to the sanctuary. Our Orphan Rehabilitation Program (ORP) receives a patient or two around spring time every year and is a role we cherish. There is nothing quite like being a mother to a joey devil and seeing them develop to maturity either within captivity or reintroduced back into the wild. The sanctuary is committed to the long term conservation of this now vulnerable species, our team is made up of a group of knowledgeable, qualified, enthusiastic and passionate staff that bring a range of skills. Our intention is to apply best practice methodology and align with Industry Programs to ensure the long term survival of these truly unique species.

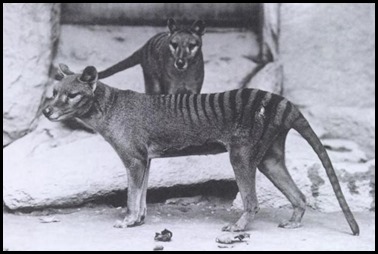

We walked past a model of a thylacine and later found this picture taken in 1906, Washington D.C. Zoo.

The thylacine, commonly known as the Tasmanian tiger (because of its striped lower back) or the Tasmanian wolf. Native to continental Australia, Tasmania and New Guinea, it is believed to have become extinct in the 20th century – recorded on the 7th of September 1936, when the last one died in Hobart Zoo, the first known land species to become extinct in Tasmania, declared so in 1986. It was the last extant member of its family, Thylacinidae; specimens of other members of the family have been found in the fossil record dating back to the late Oligocene.

The endangered numbat – picture by Martin Pot

Surviving evidence suggests that the thylacine was a relatively shy, nocturnal creature with the general appearance of a medium-to-large-size dog, except for its stiff tail and abdominal pouch (which was reminiscent of a kangaroo) and a series of dark transverse stripes that radiated from the top of its back (making it look a bit like a tiger). Like the tigers and wolves of the Northern Hemisphere, from which it obtained two of its common names, the thylacine was an apex predator. As a marsupial, it was not closely related to these placental mammals, but because of convergent evolution it displayed the same general form and adaptations. Its closest living relative is thought to be either the Tasmanian devil or the numbat. The thylacine was one of only two marsupials to have a pouch in both sexes (the other being the water opossum). The male thylacine had a pouch that acted as a protective sheath, covering his external reproductive organs while he ran through thick brush. The thylacine has been described as a formidable predator because of its ability to survive and hunt prey in extremely sparsely populated areas. The thylacine had become extremely rare or extinct on the Australian mainland before British settlement of the continent, but it survived on the island of Tasmania along with several other endemic species, including the Tasmanian devil. Intensive hunting encouraged by bounties is generally blamed for its extinction, but other contributing factors may have been disease, the introduction of dogs, and human encroachment into its habitat. Despite its official classification as extinct, sightings are still reported, though none has been conclusively proven. Time for quoll feeding.

An Eastern quoll snacking on dog biscuits. The animals here are monitored and any getting too fat are put on strict diets. This big fella is off meat at the moment.

The eastern quoll. Description – Fawn Rufous or black fur with white spots on body, no spots on tail. Adults length (head to tail) 45 cm to 70 cm, weight 0.7 – 2 kg.Habitat – Open forest, scrubland, heath, grassy areas and agricultural areas. Eats – Feeds largely on insects but also eats fruit, small mammals, lizards and carrion. Population and distribution – Eastern and northern Tasmania. Population undergoing significant decline. Numbers in the low thousands. Extinct in former range on mainland in south and east. Last mainland sighting was in Neilson Park in Eastern Sydney in the 1960’s. Threats – Habitat Clearance, introduced predators/competitors and road kill. Behaviour – Solitary, nocturnal, terrestrial Life Span – up to 3 years in the wild.

A cute picture on the adoption card. The devil is an iconic symbol of Tasmania and many organisations, groups and products associated with the state use the animal in their logos. It is seen as an important attractor of tourists to Tasmania and has come to worldwide attention through the Looney Tunes character of the same name. As of 2013, Tasmanian devils are again being sent to zoos around the world to ensure this funny little chap is not lost forever. We boarded the trusty ‘ol gal once more to go on our night tour of the road between our camp and the Interpretation Centre. Our driver told us that the animals were all perfectly used to car lights but if we stepped out they would scare immediately and bolt. Sadly, Tasmania has the highest roadkill in the world, certainly we can attest to that fact with the sheer numbers we have seen every day whilst out and about in Mabel. The experts say that if every driver slowed to 65 km from dusk to dawn the numbers killed would drastically be reduced........

A possum frustrated by the steel band stopping him from climbing the telegraph pole.

Our driver was so excited we had seen so many animals that he just kept going – we didn’t get back to Mabel until just before midnight, thrilled at all we had seen. We were all ecstatic to glimpse a Tasmanian devil in the wild, many pademelons, a few possums and the very pretty Bennett’s wallaby and lastly our favourite, wombats.

.

ALL IN ALL SUCH A VARIETY REALLY, REALLY GOOD - VERY LUCKY TO SEE ALL WE DID |