Fare Potee Museum

Beez Neez now Chy Whella

Big Bear and Pepe Millard

Tue 3 Sep 2013 22:17

|

Fare Potee Archeological

Museum

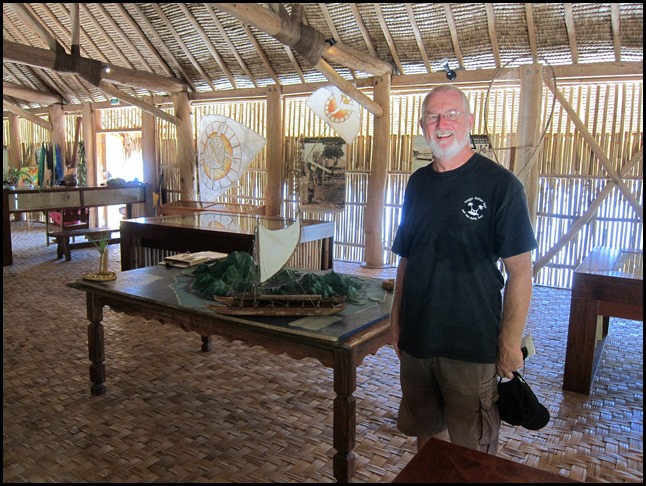

We bimbled around the sacred site and

then visited the very impressive long house, now

serving as a cultural museum.

Two lovely ladies welcomed us and in

perfect English told us a little about their work, promoting the heritage of

Huahine. Behind Bear, it was nice to see kites.

Flying kites always was, and has

recently been revived as an integral part of initiatory education - it was felt

that the handling of a kite improved knowledge of the wind, the making was a

team effort and at the end of the day it was just for pure fun. Elders today can

remember kites with wingspans up to eighteen feet. The tradition which lasted

until the 1960’s has only been revived because there are still enough of the

older generation to hand on the knowledge. The Opu Nui Association organises

competitions not only on Huahine, but Hawai’I and Japan.

It began with a challenge. When Hiro

(a half-god) was still young was challenged by his brothers to take part in a

uo’ contest. Following his mother’s advice, he used atae sheets for the sails

and ‘uo (dry films from the trunks of banana trees) for the string and the tail.

Hiro’s kite went high in the sky to freeze there forever and form a star

constellation. Te ‘Uo a Hiro or as we know it Scorpio.

Two families of kites are the most

traditional: the ‘uomenemene, which resembles a sea

turtle (honu) and the ‘uo manu, the shape of a manta

ray (faimanu). Bamboo was used for the frame, the central rib and the

spacers. Flexible, light hibiscus for the outer frame. The whole thing was

covered in tapa cloth. The tail, which could many feet long, was made with

purau bark.

In the past, kite flying competitions

were held every Saturday, but only men were considered apt enough to make them

fly. Women have been participating since 1996. Contests took place primarily on

the beaches. The length of the string was exactly the same for all entrants.

Marking was carried out during one

minute, the kite was held aloft, the string held by

another without pulling, as this was not allowed, on a gust of wind the kite was

let go and hopefully it shot into the air on a good gust. The winner was the

kite which climbed the highest in the air.

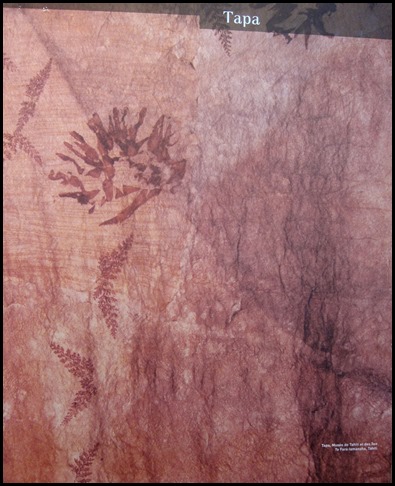

Tapa, typically made by women, men

were not excluded from the task as they planted offshoots of breadfruit

(‘uru) and mulberry.(aute) and the removal of insipient buds.

Thus perfectly smooth tillers made it possible to obtain a completely homogenous

fabric. After the bark is separated from the wood, the women took over. The bark

was put to soak for two or three days in a brook. Then it was scraped with a

clam shell, removing all the external bark. The bast, the fibrous part of the

plant fabric, was all that was left. The bands of bast were rolled in banana

leaves and was to rest for between one and three days; the fibers were then

beaten in order to interweave them. The fineness of the finished tapa was

dependent on this bit of the process. A specific beater was used made from

‘aito wood. After the beating, the parts were stretched by stones. They

were dried in the shade before the sun gave them their final consistency and

colour, which was specific to each tree used. White and resistant from aute,

beige and rougher from ‘uru, red-brown and thicker from banyan.

Tapa was often left in its natural

colour but pieces could be dyed in yellow or red for clothing. A rectangle,

tiputa was wrapped around the waist. A maro was a long, narrow piece

passed between the thighs and around the waist. Tapa could also be used as a

means of payment.

Colours are created thus:

Brown – with the bark of the ‘aito or

ti’ a’iri

Red – with a mixture of mati fruit

and tou leaves

Black – with the sap of the

fe’i

Yellow – with the root of the nono

Dark Yellow - with the root of the

re’a or the tamanu fruit.

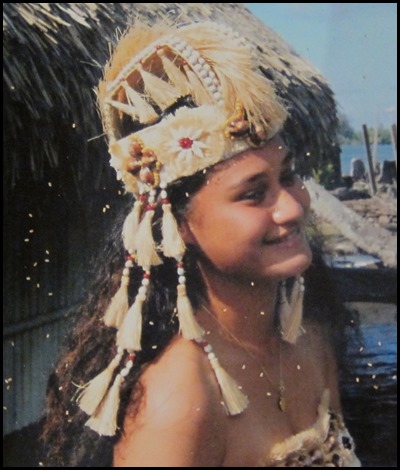

What a

story

The skirt and its

detail still look amazing

.

A model of a traditional

boat.

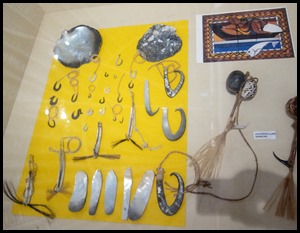

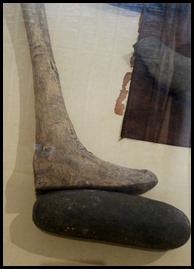

Fishing hooks and

lures.

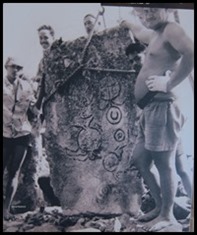

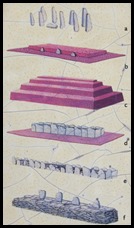

We looked at the collection of archaeological pictures and saw how a

marae was constructed.

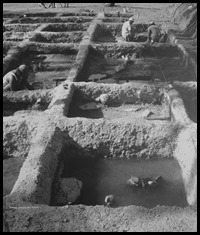

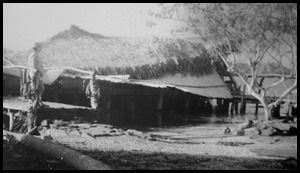

Before,

during and after restoration of the long house.

We enjoyed the exhibits.

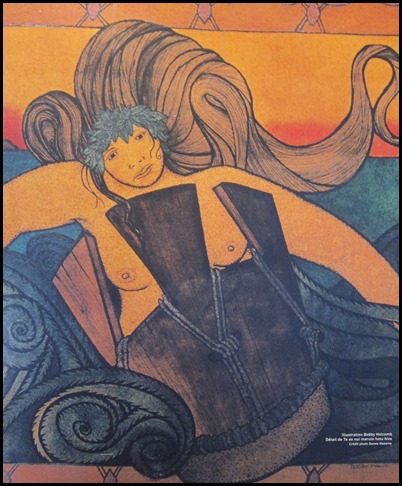

Tutapuarii, chief of the Leeward

Islands, had a daughter called Hotuhiva. From early

childhood she had a boyfriend, Teaonuimaruia, with whom she spent all her time.

Tutapuarii left Huahine to go and live in Ra’iatea; he took his daughter with

him. Her health declined and she felt sick. The most famous medicine woman on

the island tried her best, in vain. Hotuhiva said “E ere to ‘u ma’i i te ma’i

tino, e ma’i mana’o ra”. (It isn’t my body but my mind which is sick). Her

father sent her in a great sacred pahu or drum, according to others, in

a great sacred a’ano or water vessel made of coconut shell. Mara’ai,

the south-east wind blew her for two days and two nights and carried her near

the island of Bora Bora, then called To’erau-roa. The north-west wind then rose,

which pleased her father as he knew this wind would carry his daughter to

Huahine. She landed, exhausted, at a point named ever after – Manunu (Great

Fatigue).

Informed of the arrival of a

beautiful young lady, the chief of Maeva village ordered two of his young

warriors to fetch her. He took her as his wife but soon he knew she would never

belong to him. Out of spite, he gave her each night, to a different man of his

choosing.

Teaonuimaruia finally recognised her,

killed the chief and married her. Their union sealed the unification of the

whole island and started Te-pa’u-i-hau-roa, the first dynasty to reign over

Huahine. The couple had four sons, then Teaonuimaruia

died. Hotuhiva then married a chief from Matahiva and bore four more sons. These

eight boys, divided the land into eight districts and reigned over them. Still

eight villages to this day. The four on Big Huahine – Maeva, Fare Fitii and

Faie. The four on Little Huahine – Maroe, Parea, Tefareii and Haapu.

After reading this story, we bade

farewell to the ladies and headed back to the car.

.

ALL IN ALL NICELY PRESERVED

FOR FUTURE GENERATIONS

|