Jackson Bay

|

Jackson Bay and Settlers

Cemetery  We jumped up this morning with the

plan to drive the thirty miles from Haast to visit the remote outpost of Jackson

in the opposite direction of the Haast Pass. We crossed the Okuru River and

looking left had a view of the Southern Alps.

Looking right from the bridge, in the

distance we could see the Tasman Sea, very quiet this

morning.

Looking out as we crossed the Turnbull River. In

between bridges the road made us feel we were going a

long way toward World’s End.

The Waitoto

River, at least we saw some lowering fishing jetties here.

Our last bridge crossed the Arawhata River.

Some motorists might consider giving way at the many

one-lane bridges an inconvenience, just think

back to before the bridges. The creeks and rivers were dangerous to cross on

foot when in flood; in fact the cold, swift Haast could be deadly at any time.

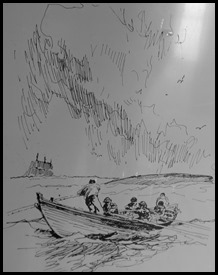

Many travellers risked their lives trying to cross rivers aboard flimsy rafts

and canoes before Government-registered ferryboats were put into service. Ferrymen could be relied upon to judge the state of a

swollen river and take passengers across safely in clinker-built rowing

boats.

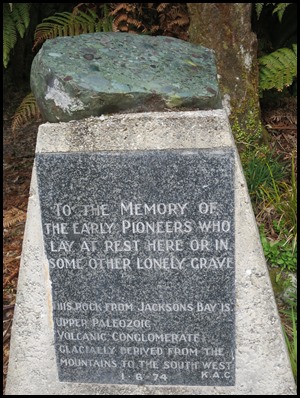

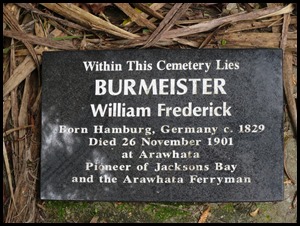

A sharp right at the end of the bridge

and we saw the sign for the Pioneer Cemetery. There

was a nice plaque, then a few steps into the woods

and a very poorly looking sign.

Our much favoured pastime of gravestone reading was indeed limited here.

Further into the

woods we found James Heveldt, died aged twenty

on the 31st of July 1901. What was amazing, his headstone

was wooden, façade intact just, sadly very rotten. We do hope the DOC put

a little cover over him, it would be such a shame to lose this memorial.

Back in Mabel no more than about a

hundred feet beyond James – above, was this massive

landslip, the Pioneer Cemetery had come very close to being lost

completely. Ten minutes further on we could see Jackson

Head. Jackson Head, which protects the anchorage, is

formed from sandstone, limestone and conglomerate. Outcropping on the ocean side

of the Wharekai Te Kou walk, the conglomerates create highly unusual patterns

seldom seen on the coast. The low ranges inland are built of harder, older rock

– greywacke and granite formed more than four hundred million years

ago.

Pre Māori tribes prospered in

this area around seven hundred years ago, trading valuable greenstone – jade,

from the Red Hills and Cascade River valley, the population is estimated to have

been between two and three hundred. By the time the Europeans arrived the heyday

of Okahu was over. Sackings by tribal parties and sealers reduced their numbers

radically.

The wharf

of the tiny fishing village of Jackson

Bay.

Jackson Bay was named Open Bay by Captain Cook; the origins of its current name are obscure. Possible namesake sources include: Port Jackson, New South Wales; James Hayter Jackson, a local whaler; or William Jackson, a sealer said to have been part of a party that was marooned in the area in 1810.

Seals were an important resource for the Okahu Māori, who ate the meat, used the skin for clothing and made fish hooks and other utensils from their bone. But pakeha sealers who started arriving in the late-18th century were interested in the animals for their skins, eating the meat only when other food was in short supply. As many as ten ships would be moored in the bay at one time, and seals were plentiful; one party of nine took eleven thousand skins from the Open Bay Islands in 1810. But that rate of kill made it a short-lived industry, from which the seal population has still not recovered. Whaling was a more dangerous occupation than sealing. Gregarious whales feeding inshore were quite easily harpooned, but in their death throes could smash even a sturdy whaleboat to bits or drag it under the water. There was a whaling station in Jackson Bay, boats rowing out to catch them and hauling their carcasses back to be boiled for their oil onshore. Spirited whaling songs which are still sung today no doubt helped boat crews overcome their fear and fatigue. Those who came here after the whalers had left came in search of grazing land or minerals went unimpressed. Claude Ollivier, who arrived with his brother Charles on the schooner Ada in 1862, caught pneumonia in wretchedly wet weather and died. The grave where Charles buried him, by “that dreary, inhospitable shore”.  Jackson Bay is a

gently curving bay fifteen miles wide, located on the West

Coast of New

Zealand's South

Island. It faces the Tasman

Sea to

the north, and is backed by the Southern

Alps. The westernmost point of the bay is marked by the

headland of Jackson Head; in the

northeast the end of the bay is less well defined, but the small alluvial

fan of

the Turnbull and Okuru

Rivers might be considered its farthest point.

The small Open Bay

Islands lie five kilometres off the coast at

this point.

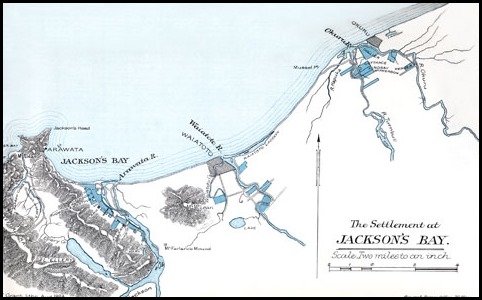

The bay marks a major change in the terrain of the west coast. To the north, narrow fertile plains lie between the mountains and the sea, allowing for moderately intensive farming of livestock. To the south, the coastal plains disappear as the land becomes steeper and more majestically mountainous. Within 60 kilometres, the first of the deep glacial valleys that further south become the fjords of Fiordland start to become evident, with Lake McKerrow at the foot of the Hollyford Track. The bay marks the farthest extent of the West Coast's road network: the small road which meanders along the coast from Haast, 32 kilometres to the northeast, terminates at the sleepy fishing village of Jackson Bay, close to Jackson Head. This was the site of the landing of the early settlers of the area, and is close to the mouth of the Arawhata (or Arawata) River. The third river to enter the Tasman along this stretch of coast is the Waitoto River, which enters the bay six miles to the east of Jackson Head.

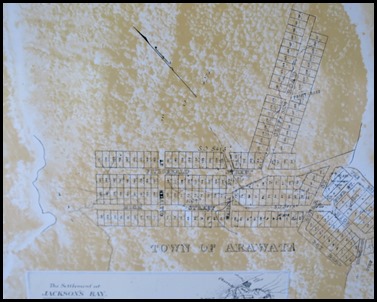

The information boards were in their own shelter, we went across to learn more. Despite the grim experience of the 1860’s gold prospectors, Jackson Bay was chosen as the centre for a special settlement under the assisted immigrant programme in 1874. The dream was of a thriving farming district served by a seaport town that would rival the likes of Hokitika and Greymouth. Fisheries, forests, mineral deposits and other natural assets might be exploited as the south was opened up. Although surveyors took a lot of trouble

to fit features in with the landscape it was perhaps just as well Arawata

Township was never completed according to plan. Cliff Road would have been

difficult to achieve, especially in such a straight line, and the Fitzgerald and

High Street subdivisions would have been plagued with drainage problems. In an

earlier scheme the town was to have been by the Arawhata River, with a road

connecting it to the port of Seacombe at Jackson Bay. Jackson Bay Settlement did

become spread out between the bay and Okuru. The isolation from each other added

to their difficulties.The settlement, spread out between Smoothwater and Okuru,

was immediately plagued with problems. Above-average rainfall in the first two

years rotted crops in the ground, caused a bewildering amount of sickness and

isolated families on the wrong side of the floodwaters. Land allocations were

muddled, many farm blocks were too small, and the lack of a wharf made supplies

irregular. Sales of any surplus produce to outside markets seemed a dim

prospect. Pleas for a wharf were ignored by a Government which had apparently

quickly reached the conclusion that enough money had been wasted on the

settlement.

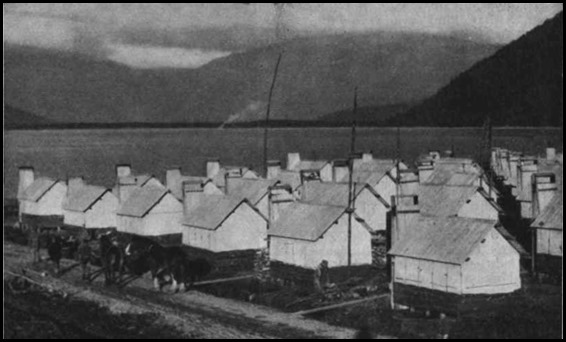

The first contingent of hopefuls set foot

on the beach at Jackson Bay in early 1875. Others followed over the next two

years until the population peaked at about four hundred. They were a mixture of

nationalities including English, Irish, Scandinavians, Germans, Poles and

Italians. Few were farmers, and they knew little about breaking new land under

the difficult conditions they were about to meet. Within a few years families

were pulling out, beaten. But although hopes were dashed, a few gritty settlers

stayed on as subsistence farmers, some fishing, sawing timber or digging for

gold to get by. As agriculture developed and transport improved, the farms grew

more prosperous. There are descendants of special pioneers still living in the

district.

So many places and islands we have visited

have begun a conversation as follows. Fancy after weeks

at sea, climbing from the boat into a dinghy, being rowed ashore, dropped with

the minimal of possessions on a beach, watching the dinghy row back to the boat

and wave as the boat disappears over the horizon. Not so bad if you

have come from the Orkneys or the Shetland Islands but if you came from the East

End, Islington or Bow, the shock must have been tangible. Many had fresh water

rivers close to hand but we have read of saltwater creeks with miles to the

nearest drinking water. We have read of husbands dying, leaving a wife and

several children to ‘get on with it’. It never ceases to stop us in our

tracks.

The Jackson Bay workmen set up camp to build the new

settlement.

Beside the information boards was a lone four-sided

chimney, all that remains of an early

house.

Opposite was the only

eatery – closed for the winter, the Cray Pot is well

known in the area. Complete with al fresco

seating.

Talley’s and the Fiordland Lobster

Company Limited, are the businesses we saw.

A

‘one careful owner’ outside, not sure

what.

Behind we found a few houses, but saw no one.

New

and old. Our first rhododendron in

bloom.

One sole

house along our return journey caught Bears eye, especially the whale

cervical bones used as gatepost caps, could be any age. I liked the homemade bridge across the drain.

The road back to Haast.

No Tesco grocery deliveries

out here or mobile phone network signals.

.

ALL IN ALL IT FELT VERY REMOTE - THE END OF THE WORLD A VERY ISOLATED PLACE |