DM History of Isishweshwe

Beez Neez now Chy Whella

Big Bear and Pepe Millard

Fri 10 Jan 2020 23:17

|

The History of a Material called

Isishweshwe  The model of the

Caravel Bartholomeu Dias in the

Granary Building where we entered the Dias Museum Complex. In the reflection –

Bear, Crocs bottom left, Larry, me, and Allen at the pay desk. This blog is

about the history of a material called isishweshwe, it will be of

little interest to most but it is written for my sister-in-law, Cecily who is

the Queen of the Sewing Machine, making gorgeous quilts and patchwork

masterpieces. The display was an interesting look at South Africa from a social

angle whilst looking at the material through the ages, as soon as I saw all the

old pictures I was hooked.

The team who put

the display together.

This travelling exhibition on the

origins of isishweshwe has been developed by Iziko Museums of South Africa for

Museum Services, Western Cape Department of Cultural Affairs and Sport. It is

based on the exhibition The Isishweshwe Story:material women? designed by the

Iziko Social History Department and made possible by the donation of a large

collection of isishweshwe and related artifacts, as well as images by Dr

Juliette Leeb-du Toit.

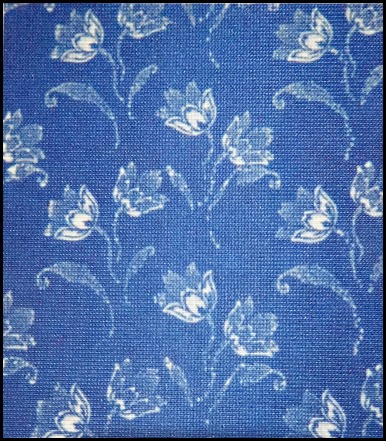

What is isishweshwe? Isishweshwe is a

sturdy, resist- or discharge-printed cotton fabric with regularly spaced, small

patterns, widely used in southern Africa for women’s, and increasingly men’s

clothing. It was introduced as blue print from Europe to southern Africa in the

19th century by missionary traders, and became a marker of colonial influence

and Christianity amongst indigenous women. Today it is a much-loved African

textile tradition, regarded as a national fabric in many southern African

countries, enjoying unique importance in the history of culture, dress and

fashion.

The term isishweshwe is derived from

the Sesotho word seshoeshoe (pronounced “seshweshwe”), as King Moshoeshoe I is

said to have condoned the use of European blue print from the Paris Evangelical

Mission Society in the mid-1830s. In the Eastern Cape people use isiXhosa names

derived from the word “German” to describe it: amajamani, ujamani, jelmani or

jereman. The Badepi call it motoishi, a Sepedi variant of the Afrikaans or

German word for German (Duits or Deutsch). It is also known as Duitse sis and

German print.

The Wreck of the

Visch at Camps Bay by J. Leeuwenberg. Oil

painting. 1740. Image courtesy of the National Library of South Africa (Cape

Town). Note the blue and white chintz dress on the

right.

Petticoat of Indian chintz (Indienne), with a border design

in various shades of indigo. Probably Coromandel Coast, India, c. 1775-80.

Presented by Marianne Pfeiffer, Iziko Soc Hist. (Photograph:Carina

Beyer).

Blue print, isishweshwe’s precursor:

Sea routes opened by the Portuguese, Dutch and British during the 16th and 17th

centuries led to European domination of the Indian Ocean trade routes and new

colonial settlements. This opened massive trade possibilities for Europe,

including imports of multi-coloured Indian cottons known as calico, chintz, or

Indiennes, hitherto unknown to most Europeans. These sought-after fabrics were

hand-made, using natural dyes of which indigo blue was amongst the most

significant.

As they discovered the Eastern secrets

of colouring calicoes using resist pastes and carved woodblocks, Europeans

started copying these techniques at home. To cut costs, they imported only raw

materials not available in Europe, such as cotton and indigo.

Blue print, using indigo only, was

being hand-produced by small “blue-printers” in villages all over Central Europe

by the early 1800s. By the mid-1800s the process had been mechanised in the

industrial centres of Europe and Britain using the discharge technique, which

imitated the hand-made, resist-dyed blue prints. Factories sprang up around

towns such as Manchester (England), and many joined the Calico Printers’

Association.

The

Schoolmaster Reading De Zuid-Afrikaan, by Charles Davidson Bell

(1813-1882). Watercolour, 1850. Note the blue and white skirt worn by the

servant holding the ostrich feather fan, (Iziko William Fehr

Collection).

Blue Print at the Cape: The Dutch

established the settlement at the Cape as a halfway station on the sea route to

the East. From the late 1600s it absorbed quantities of the Asian exports bound

for Europe, including indigo and Indian calicoes, which were used for clothing,

curtains and bed drapes. Indigo blue cloth also came to characterise the dress

of slaves, whether plain or patterned.

By the early 19th century,

German Morovian missionaries and their converts, such as those at Genadendal,

wore blue print, known by the German name of blaudruck. Many Germans

came to what is now KwaZulu-Natal and the Eastern Cape in the mid-1800s,

settling as artisans, Lutheran missionaries or farmers. For working dress, and

as evidence of their homeland Protestant identity, many wore

blaudruck.

Boer women also

adopted the fabric on farms and in small rural towns, and appreciated it for its

quality and strength.

A changing tradition: As European

powers penetrated deeper into southern Africa, and missionaries arrived to

spread Christianity in the 19th century, they encouraged woman to cover their

bodies with European-manufactured cloth, including blue print. This fabric, the

predecessor of isishweshwe, resonated with Africans, and they began to merge the

new fashion into their cultural practices, a creative process that continues to

this day. Isishweshwe continues to have many cultural applications in southern

Africa, especially amongst women, and can be seen as a marker of southern

African cultural identity.

Members of the

Steyl family in a Boer concentration camp during the South African War.

Near Bloemfontein, 1899-1902. (Image courtesy Free State Provincial Archives).

Note the blue print bonnet (kappie) of the seated woman second from the

right.

Women collecting

wood. Eastern Cape, late 19th century? (Image courtesy Nelson Mandela

Metropolitan Library Service).

Blue Print becomes Isishweshwe: At

first, during the 19th century, the best quality mass produced discharged prints

were imported to South Africa from Germany. However, British factories had

cornered the market by the second decade of the 1900s.

In 1948 the British-based Calico

Printers Association established the Good Hope Textile Corporation in South

Africa with encouragement from the South African government. The company was set

up in a specially created village – Zwelitsha, near King William's Town – to

facilitate company access to cheap labour.

In the 1960s, trading as Da Gama

Textiles, the Corporation started making discharge-prints under the “Three

Leopards” logo, and by the late 1980s/early 1900s obtained the copyright for a

range of British designs with the “Three Cats” logo.

In South Africa the fabric had been

known in the vernacular as isishweshwe since the 1980s, and today Da Gama

Textiles is the world’s only manufacturer of what is known as “genuine

isishweshwe,” i.e., fabric produced using the discharge-printing

method.

Bonnet

(kappie), machine-quilted, donated to the Amathole Museum in King

William’s Town, Eastern Cape by Rina van Graan. Probably early 1900s. From the

collection of the Amathole Museum (Photograph: Carina Beyer).

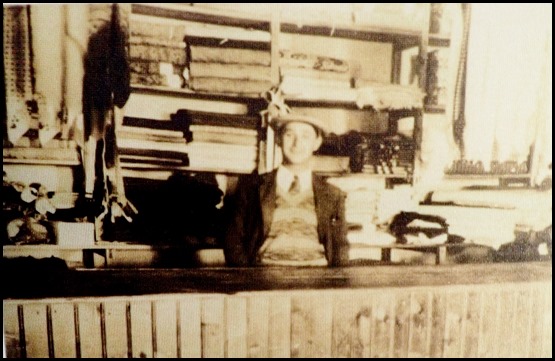

Shop assistant

Oscar Marcus in Solomon Fein’s shop in Concordia, Namaqualand, Northern

Cape c.1930. (Morris Boiskin Namaqualand Collection, Special Collections,

University of Cape Town Libraries.) Jewish shops selling their wares, including

fabrics such as isishweshwe, were dotted all over South Africa. Many Jews also

made a living as itinerant traders (smouse), peddling wares such as

isishweshwe.

Blue Print in Europe Today: Originally worn

as peasant and work-wear in countries such as the Netherlands, Germany, Austria,

Czechoslovakia and Hungary, blue print became associated with European regional

and Protestant costume, and was often used to express nationalist sentiments.

Blue print in Europe today is worn in a context of nostalgia and as folk

costume.

Produced and used

in many rural regions in Germany, blaudruck became associated with volkisch

thought and national socialism in the years before World War II. Hungarian

kekfesto continues as daily dress in some rural communities, while it also

features in Hungarian regional dress. It has signaled a patriotic love for the

country since the peasant revolts of 1844. Dutch blaudruck, worn in the past by

workers, is now used to accessorise some regional costumes, used for items such

as head cloths and aprons.

A shop selling

blue print (kekfesto) in Szentendre, near Budapest, Hungary, 2006.

(Photograph: Kirsten Nieser). Besides being worn by labourers; as part of a

rural tradition; or (later) as a sign of nationalism, kekfesto coud also signify

“Christian wear”. bereavement and festive wear. A parallel South African use may

be found among widows in many African independent churches who wear isishweshwe

for the period of mourning.

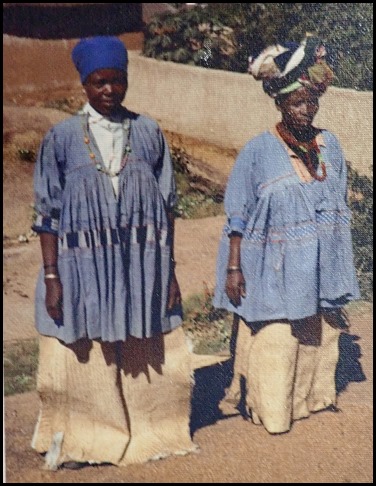

Marching Mbanderu

women in Okahandja on Herero Day, 26th of August 1960. (Image courtesy of

National Archives of Namibia/Zambik Collection). In Namibia and Botswanna,

Herero women copied Victorian era dresses and adopted blaudruck (blue print) and

other cloths worn by German settler women.

Bapedi women

wearing smocks, Phokwane Limpopo, 1973 (Photograph: John

Kramer).

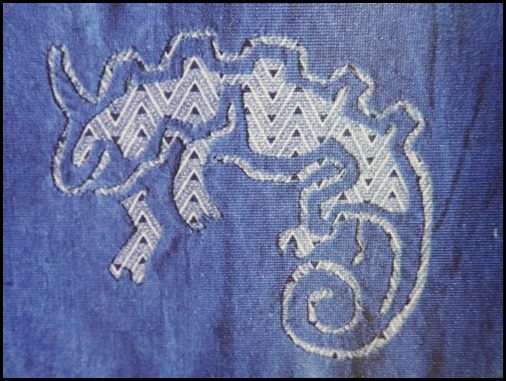

Reverse applique

motif of a chameleon, designed and made by Marie Peacey, 1980s.

(Photograph: Carina Beyer).

Isishweshwe for

social statements, solidarity and sewing: During the 1970s and 1980s many white

South African women wore isishweshwe to signal solidarity with the

anti-Apartheid struggle, or to convey their desire to be part of an alternative

culture. Needleworkers also liked to use it for applique and patchwork when

making items such as quilts and jackets.

Today community initiatives which

encourage the development of sewing skills to generate income often use

isishweshwe. The fabric is also a popular choice for making accessories and home

decorations, as well as souvenirs destined for the international market. The

wearer or user of such items at the same time stakes a symbolic claim to a

southern African tradition.

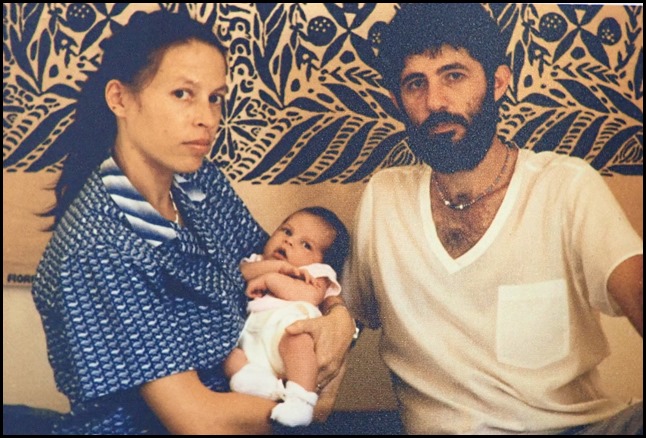

Beth and Desmond

Smart announce their firstborn, Rebecca Joy. Durban, KwaZulu-Natal, 1986.

(Photograph: Desmond Smart). Beth’s dress was made by a family friend, Mary

Butlin, who was a professional dressmaker working in Hillbrow at the

time.

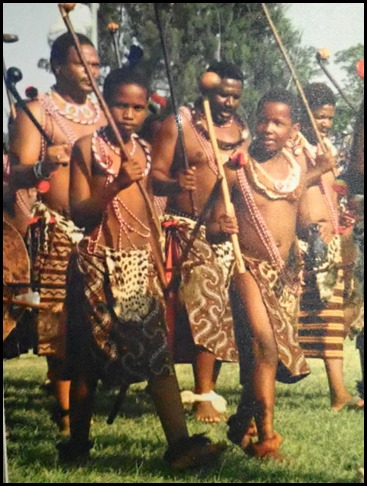

An emaSwati

amabutho group wearing sidvashi (skirts) with libululu (snake pattern)

design and amajobo (loin skins), at Swazi King Mswati III’s birthday

celebrations. Manzini, Swaziland, 2005. (Photograph: Kirsten Nieser). In

southern Africa isishweshwe is traditionally associated with women’s dress,

though in Swaziland and Lesotho it has been worn by men for cultural display.

The libululu design is the King’s favourite.

Unidentified women

attending Moshoeshoe I Day celebrations. Maseru, Lesotho, 2008.

(Photograph: Juliette Leeb-du Toit). This anniversary is celebrated annually on

the 11th of March. Most people wear isishweshwe as a sign of their cultural

identity, and women vie for position of the “ideal Sotho woman”. When the Queen

of Lesotho wears a new isishweshwe design demand for the design rises

steeply.

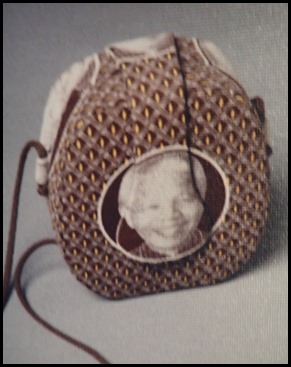

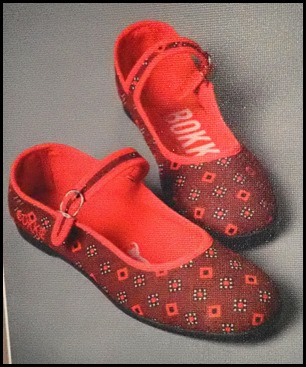

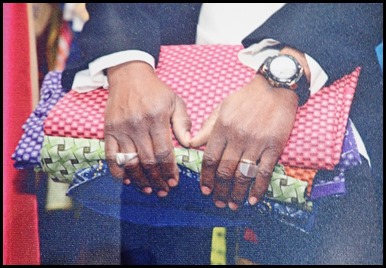

Bag designed by

Ruff Tung. Purchased in Johannesberg, Gauteng, 2005 Da Gama “Madiba

Range” fabric. Juliette Leeb-du Toit Collection, Iziko Soc Hist. Isishweshwe covered shoes with Bokkie label. Cape Town,

c.2010. (Both photographs by Carina Meyer).

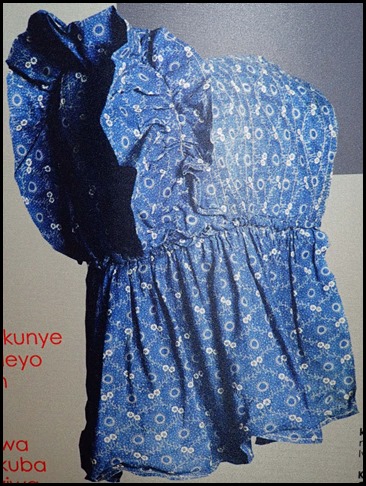

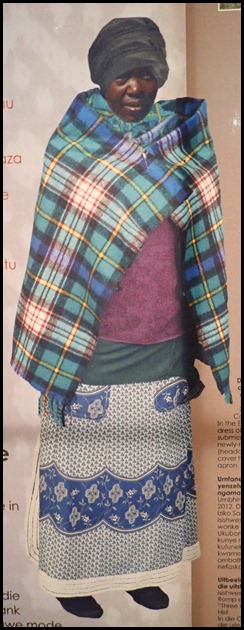

Depiction of

umakoti – a newly-married Xhosa woman – created for the exhibition The

isishweshwe story: material women? (Photograph: Carina Meyer). Skirt and apron

purchased in Idutywa, Eastern Cape, 2012. Da Gama “Three Cats” fabric, Juliette

Leeb-du Toit Collection, Iziko Soc Hist.

In the Eastern Cape isishweshwe is

traditonally worn as part of the dress of a new Xhosa bride or umakoti. To show

respect and submission (ukuhlonipha) to her husband and parents-in-law, a

newly-married Xhosa woman is expected to wear her ikhatshemiya (headcloth) low

over her forehead, keep her shoulders covered, cover her hips with a blanket and

wear isishweshwe skirt and apron.

Austrian

traditional dress-and-apron outfit with Wenger label. Austria 2012.

Mass-produced resist-printed cotton. Juliette Leeb-du Toit Collection, Iziko Soc

Hist (Photograph:Carina Beyer) and two

designers.

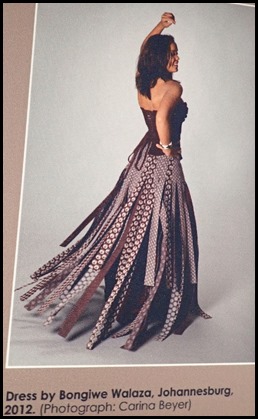

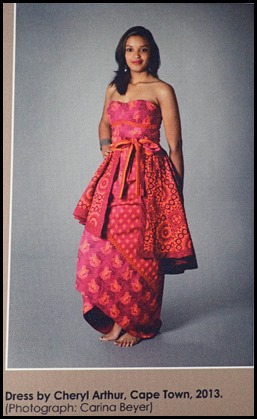

A New Isishweshwe Fashion: The

potential of isishweshwe as a fashion fabric was exploited as early as the 1970s

by South African designers and entrepreneurs such as Jutta Faulds, Helen de

Leeuw and Penny le Roy. In post-Apartheid South Africa, the fabric has been

adopted for display on international circuits by internationally recognised

South African couturiers as Bongiwe Walaza, Amanda Laird-Cherry and Palesa

Mokubung.

Locally, people who design clothes

with isishweshwe include both seamstresses working from home and increasing

numbers of small fashion houses. Many West and East African dressmakers living

in South Africa also use the fabric in their designs.

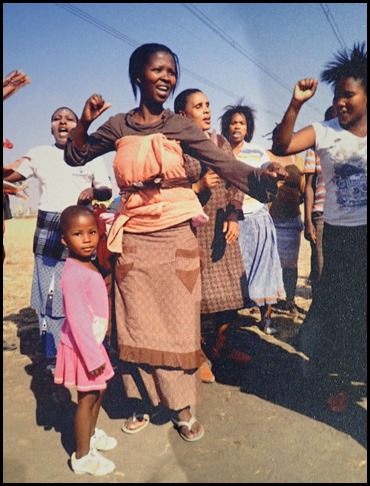

Women protesting

at Marikana the day after the 17th of August 2012 police shootings of

striking mineworkers. North West Province, 18th of August 2012. (Photograph:

Karin Labuschagne; image courtesy of Jacaranda FM). All the women depicted,

except the little girl, are wearing isishweshwe.

New colour ranges of isishweshwe tempt seamstresses,

designers and crafters alike to engage in creativity with the fabric.

(Photograph: Carina Beyer).

Isishweshwe for the future:

Users of isishweshwe adopt the fabric in ever-changing movements of creativity,

continually embracing new versions of African and South African identity.

However, it is rejected by some young city-born women as having rural and

oppressive associations. Besides its use as daily wear by women and increasingly

also by men, the cloth is imaginatively worn at both festive and informal

occasions, as traditional dress, to make a statement, or as an

accessory.

Isishweshwe’s highly

recognisable design aesthetic is being applied in new contexts, adorning objects

from book-covers to umbrellas. The Da Gama factory itself is printing its

traditional isishweshwe designs in non-traditional hues (such as pink and lime

green), and new patterns are regularly released.

Global trade competition is

threatening traditional isishweshwe markets, since the popularity of isishweshwe

has led to many cheaper imitations by local and Eastern producers. The original

discharge-print is still preferred by those who can afford

it.

Today isishweshwe is embraced as a national fabric and costume in

many southern African countries. It holds a place of unique importance in the

history of culture, costume and fashion in South

Africa.

ALL IN ALL A FASCINATING PICTORIAL

STORY THROUGH THE YEARS

AN INTERESTING LOOK AT SOUTHERN AFRICAN

CULTURE |