Rorke's Drift Overview and Site Bimble

Beez Neez now Chy Whella

Big Bear and Pepe Millard

Sat 30 Nov 2019 23:47

|

Rorke's Drift Overview and

Site Bimble

Approaching Rorke’s Drift and a mile away.

As we neared we

read an overview from our Wars of the

Region pamphlet: The Anglo Zulu War 1879. The continuing strengthening of

the independent Zulu nation by King Cetshwayo was perceived as a growing threat

to the colonists of Natal. and in December 1878 the British Colonial government

issued an ultimatum that was impossible for the Zulu nation to accept as it

required them to disband their army and swear allegiance to Queen

Victoria.

When these demands were not met,

three British columns, under the command of Lieutenant-General Lord Chelmsford,

who despite considerable experience in the field, nonetheless made the fatal

mistake of underestimating the fighting ability of the Zulus, crossed the

Thukela and Buffalo rivers and invaded Zululand.

The Zulus retaliated and on

Wednesday the 22nd of January 1879 the Zulu Army of over 20,000 warriors

attacked and overran the British camp at Isandlwana, slaughtering some 1,400

Imperial troops, colonial volunteers and native levies. Survivors of the route

fled along a tortuous trail, now known as the Fugitive’s Drift, among these were

Lieutenant Melville, who was trying to save the Queen’s Colours and Lieutenant

Coghill who came to his rescue when he was swept off his horse in the river.

Both were killed on the Natal bank of the river as they scrambled up the

hillside. (They were posthumously awarded the Victoria Cross).

After the Battle the Zulus

reserve force of some 4,000 warriors led by Prince Dambulamanzi went on to

attack the British garrison at the Swedish Mission station at Rorke’s Drift,

that was being used as a commissariat and hospital. Here the “heroic hundred”

repelled the attackers after a twelve hour battle. The British lost 17 men and

won 11 Victoria Crosses, the most ever awarded in a separate military

engagement.

There followed the massacre of a

British convoy at Myer’s Drift, the disastrous British attack on Hlobane

Mountain where the British were once again outmanoeuvred by the Zulus and only

escaped after suffering severe losses. The following day the Zulu army attacked

the British camp at Kambula and were driven off also suffering very heavy

casualties. The Zulus were again defeated at Ginginhlovu when they attacked the

British garrison besieged at Eshowe. Then came the death of the Prince Imperial,

the last hope of the Napoleonic dynasty who was killed when his patrol was

ambushed in Zululand. Finally there came the great ritual battle of Ulundi on

the 4th of July which ended with the defeat of the Zulu Army, forcing King

Cetshwayo to flee.

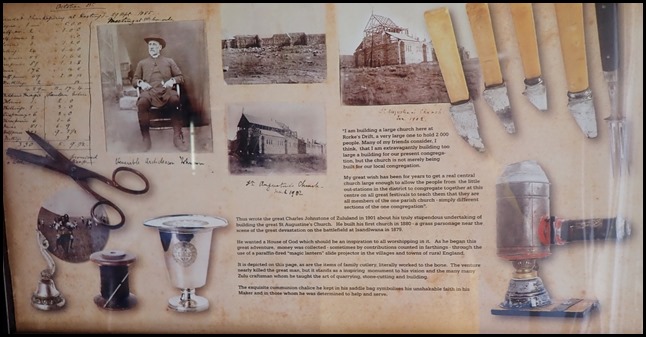

After paying the ladies at the gate who were enormously pleased to

see us, we bought a little information pamphlet and headed towards the museum. To our left a teashop, a good place to get our

bearings, on the walls were many old photographs.

From our pamphlet – Introduction:

The battle site at Rorke’s Drift / Shiyane has been considerably modified since

the battle took place on the night of the 22nd of January 1879. None of the

buildings standing at that time remain and even the vegetation in the area is

different.

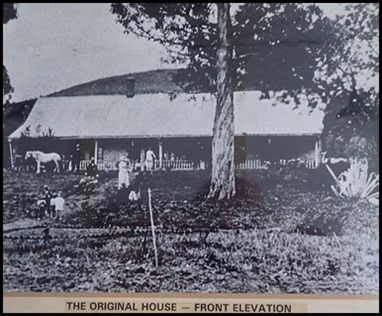

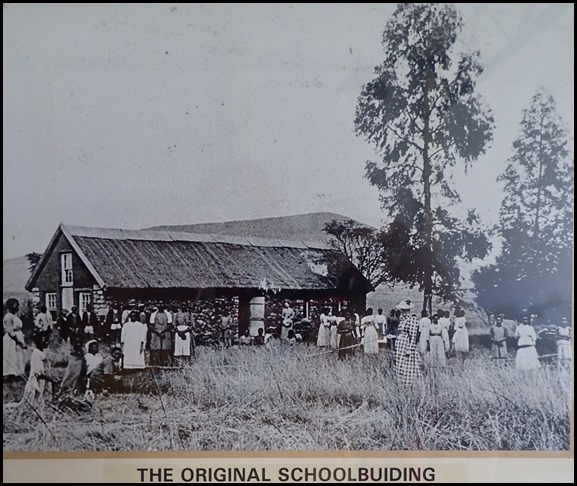

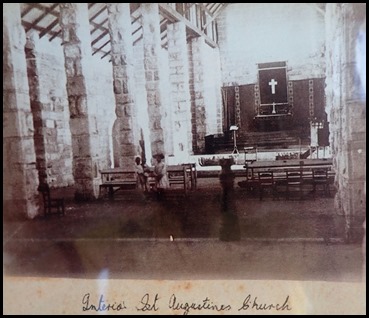

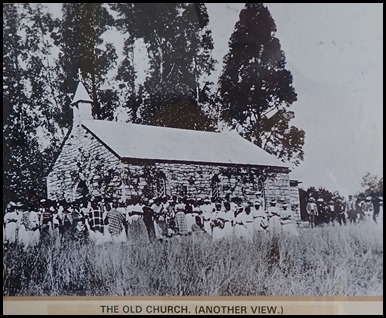

The building which was situated

on the site where the museum is now housed was built by James Rorke and became

Missionary Otto Witt’s first home. It was taken over by the British and used as

a hospital. The present church stands on the site of the commissariat store,

which had been Rorke’s trading store. The house, store and a cookhouse were the

only buildings on the site at the time.

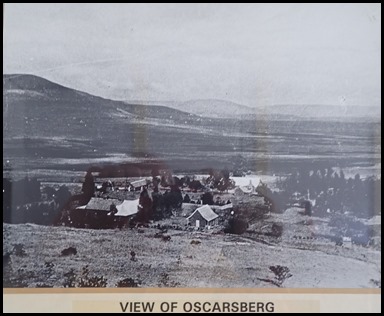

From contemporary photographs it

is evident that the country around Rorke’s Drift / Shiyane was once open

grassland, apart from a number of trees and shrubs that were planted on the

northern side of the mission station. However, overgrazing has resulted in scrub

encroachment and the spread of thornveld – a common problem in many areas of

KwaZulu Natal. Several varieties of exotic trees have also been introduced. Bear

these facts in mind as you explore the site, and try to imagine Rorke’s Drift /

Shiyane as if it were in 1879 – a lonely outpost on the border between Natal and

Zululand.

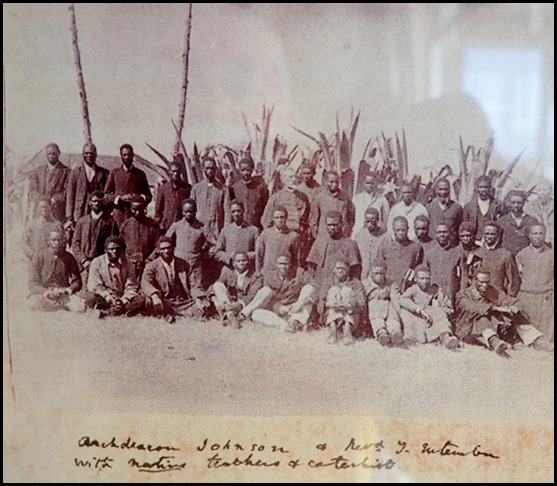

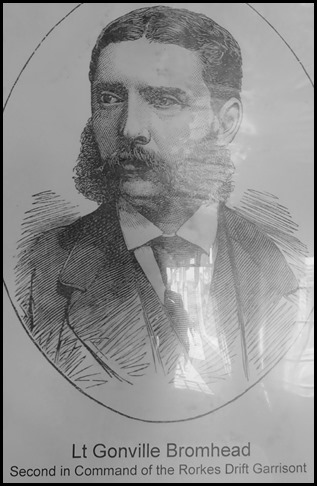

Sadly, no label to

this picture.

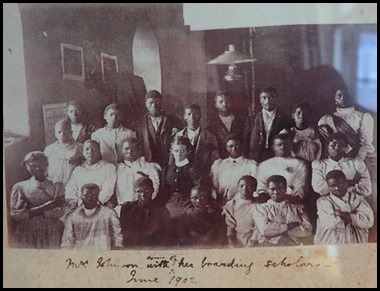

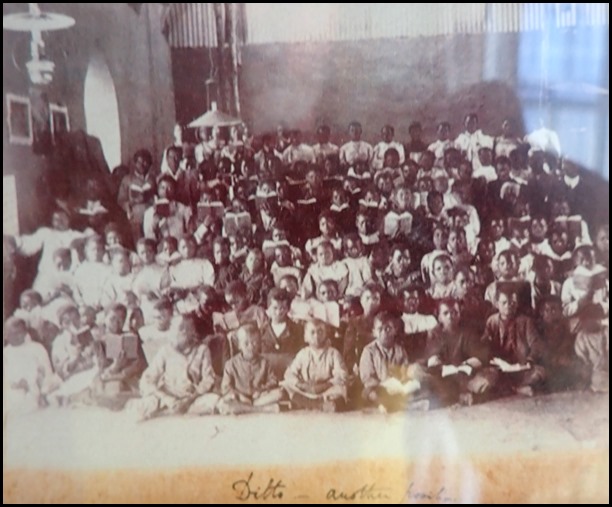

Shame about the glare but I thought

these four looked so very proud.

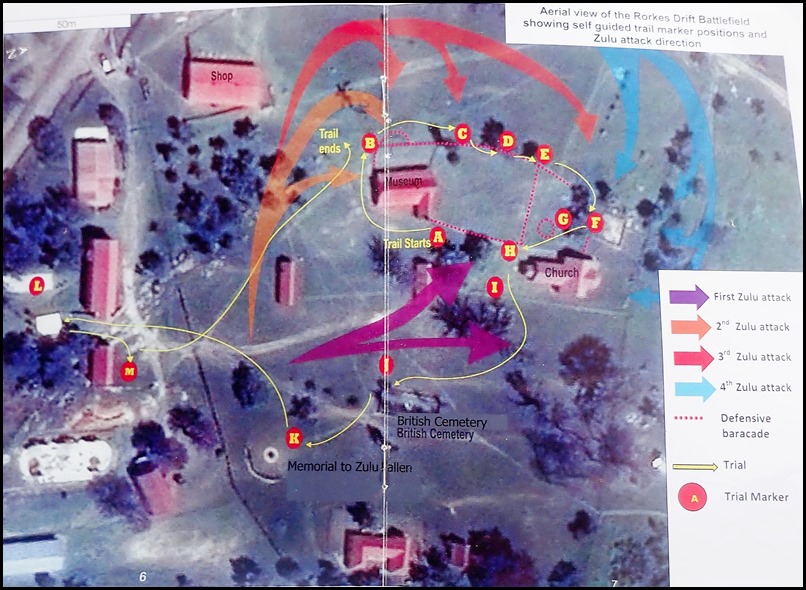

The map in

the middle of our pamphlet.

We headed for Marker

A: When the main British force under General Lord Chelmsford

crossed the Mzinyathi (Buffalo River) on the 11th of January 1879 to invade

Zululand, a small garrison numbering about 390 men, was left behind at Rorke’s Drift / Shiyane

to guard the “mountain” of supplies and the hospital. Life had been quiet for

the garrison, until the early afternoon of the 22nd of January, when disturbing

news was recived that the British camp at Isandlwana had been

overrun.

After a short discussion about

what to do, the British officers decided that their only hope of survival was to

defend the post. A barricade made of mealie bags, approximately four feet (1.2

metres) high was hastily built. The stones in the ground between where you are

standing and the church demarcate the southern defence line.

The garrison was faced with a

further crisis when 250 members of the Natal Native Contingent deserted and fled

in the direction of Helpmekaar. The British force was in a desperate situation

as a mere 139 men remained, of whom about 35 were patients in the

hospital.

Lieutenant Chard, the senior

officer present, quickly had a line of biscuit boxes placed in position to link

the southern and northern defence lines, thereby creating a smaller and more

easily defendable area immediately in front of the commissariat store, should

this become necessary.

The defence barricades had almost

been completed when the iNdluyengwe ibutho (regiment), made up of young men,

appeared round the north-western slopes of Shiyane (Oscarsberg Hill). Their

initial attacks were against the line of defence where you are now standing,

including the rear of the hospital and the commissariat building. The British

checked the iNdluyengwe with steady rifle fire, forcing them to take cover

whenever they could.

Marker B: As the

iNdluyengwe found themselves checked along the southern perimeter, they swung

round the west side of the hospital and attacked the defence positions, probing

for a weakness. The mealie bag barricade in this area had not been finished and

the British rifle fire was less intense, with the result that it was a weaker

position than others. The Zulu were thus able to get right up to the barricade

itself, and some desperate hand-to-hand fighting took place. Eventually the

British were forced to retire from this sector.

Marker C: Chard

had ordered a short “dog’s leg” of mealie bags to be built to connect the corner

of the hospital with the northern barricade. It was this cover that some of the

British soldiers retired from their positions on the north-west

corner.

The arrival of the remaining

three Zulu regiments, the uThulwana, uDloko and iNdlondlo, together with sniper

fire from sandstone caves on the slope of Shiyane, eventually forced Chard to

withdraw all the men, other than those in the hospital, to the area in front of

the commissariat store.

Zulu forces set fire to the

hospital’s thatch roof (impressive model in the

museum) and succeeded in breaking into the building. Several of the

rooms on the southern side of the building (facing Shiyane Hill) had no

inter-leading doorways, but only exterior doors and windows. As the Zulus held

the rear of the building, the men in the hospital had to break through the walls

which, fortunately for them, were made of soft mud

bricks.

By fighting their way from room

to room, the British defenders were able to evacuate most of the hospital

patients. The retreat from the hospital to the area behind the biscuit box

barricade was extremely hazardous as the intervening ground was only defended from behind the biscuit

boxes.

Dioramas in the

museum.

Marker D: As the

battle progressed, the Zulu massed on the flat land in front of you, extending

round to the eastern end (towards the river). They took cover in the long grass

and in the shrubbery and made a series of fierce attacks on the British

defences. Several warriors took advantage of the sandstone ledge below,

periodically popping up and firing at point blank range. The sandstone ledge and

the mealie bag barricade provided a difficult barrier for them to overcome.

Marker E: Where

the biscuit box wall met the barricade. From about dusk, the entire British

force occupied the barricaded area between the markers E, F and H – note how

small this defended area was.

Marker F: This

is a reconstruction of the cattle kraal which stood here at the time of the

battle and played an important part in the defence. The British were forced to

evacuate the farther half of the kraal. When the British counter-attacked during

the middle stages of the battle, the Zulus were forced to

retire.

Marker G: During

the night Chard ordered that a small redoubt be built with some of the remaining

mealie bags, in case the Zulus broke into the final defensive area. The stone

circle marks the position of this redoubt, which was about nine feet (three

metres) high and hollow in the middle. The badly injured men were hoisted inside

to offer them greater protection and snipers were positioned on the top to shoot

any Zulu who breached the defences.

Marker H:

Archaeological research has revealed parts of the foundation of the commissariat

store, which is now marked by this line of stones. Most of the foundations are

under the church.

After the battle, the British

soldiers pulled off the thatch roof in case the Zulus returned and set fire to

the building. In later years the missionaries broke the structure down and used

the stone and timber to build the original part of the church.

Marker I: The

cookhouse and ovens that were used by the missionaries and by the British stood

in this position. During the early stages of the battle the Zulus used these

structures as cover from the fierce Martini-Henry rifle fire.

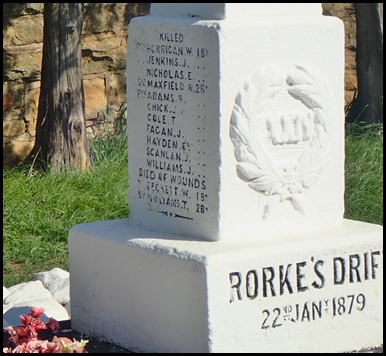

Marker J: This

is the site of the British Cemetery. British soldiers

killed in the battle were interred here, their names were inscribed on the stone

monument erected by their comrades.

Marker K: The Memorial to the Fallen

Zulu. This bronze piece, commissioned by Amafa Heritage KZN, and sculpted

by Peter Hall in 2005, was erected in 2006. It depicts a leopard, representing

the Zulu monarch, protectively covering the shields of the fallen Zulu warriors.

The tree growing in the centre of the memorial is a Buffalo Thorn (Mphata or

uMlahlankosi), traditionally used by the Zulu royal family, also used to bring

home the spirit of the departed who have died far from home, as did most of the

warriors who perished in this battle.

The bell on the hill

- Marker

L: This is the cemetery where the Zulu dead were

interred. After the Zulu retreat, most of the dead could not be retrieved and

were interred by the British in hastily prepared mass graves. The names of the

vast majority of those Zulu who perished remain lost to

history.

An aloe in

memorial white stones and the cattle

field.

This engraving depicting relief mounted troops on the morning

following the battle appeared in the illustrated London News on the 8th of March

1879, news relating to the Anglo Zulu War was followed with intense interest in

Britain.

Conclusion: When the Zulu failed to capitalise

on their capture of part of the stone kraal, the ferocity of their attacks

started to subside. From about 22:00 there were no further concerted attacks,

but simply a number of sorties involving small numbers of warriors. However,

periodic shouts of “uSuthu” kept the British defenders unnerved and prevented

them from relaxing. Occasional firing still took place from the slopes of

Shiyane and from the garden. When dawn finally broke at about 04:00 the Zulu

retired backwards towards Isandlwana.

Quite

extraordinarily, less than 150 British defenders had succeeded in warding off

attacks of some 4,000 Zulu warriors for nearly 12 hours.

A question often asked is why the

Zulu failed to capture the post at Rorke’s Drift / Shiyane despite overwhelming

odds. The Zulu force had left Nodwengu, the military establishment outside

Ulundi, on the 17th of January. While they travelled with the minimum of

supplies, the distance is over 100km and the men had lived off the land for some

of the time. On the 22nd the Zulu force which attacked Rorke’s Drift / Shiyane

had covered another 12km from Isandlwana and had crossed the flooded Mzinyathi

River. The force may already have been somewhat drained, despite the fact that

the rest of the Zulu army had inflicted a severe defeat on the British at

Isandlwana earlier in the day.

It appears too that the Zulu

attacks were poorly co-ordinated. Prince Dabulamanzi, who commanded the Zulu

force, may have been responsible for this. He was not a general, but because of

his status within Zulu society, and through his forceful personality, he assumed

command. As for the British force, it had no option but to fight. Under the

circumstances it organised well by building a very effective barricade and

having ammunition readily available. Disciplined marksmanship and cool head

perhaps won the day, although clearly there were deeds of quite extraordinary

heroism on both sides.

On the British side, eleven

Victoria Crosses were awarded for gallantry and as many, if not more bravery

awards, could have been awarded to the Zulus. 17 British soldiers were killed

along with an estimated 500 Zulu warriors. Of 20,000 rounds of ammunition which

the British started the defence, only about 600 remained at the

end.

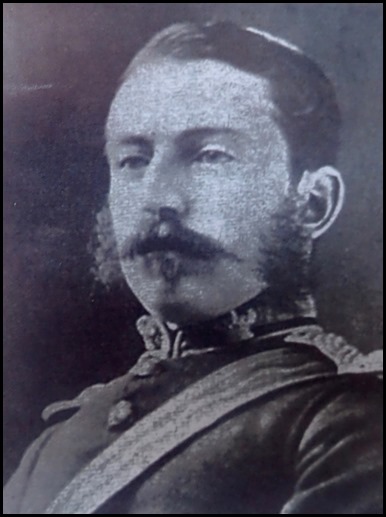

Prince Dabulmanzi KaMpande, brother of King Cetshwayo, led

the Zulu attack on Rorke’s Drift / Shiyane. This photograph was taken after the

war in about 1882. He actively opposed the post-war division of Zululand and was

killed in a dispute in 1886. He was buried at Nondweni, near present-day

Nquthu.

Lt. John Chard,

senior officer at Rorke’s Drift / Shiyane. He was one of the recipients of the

Victoria Cross for bravery at the battle. After the war he was posted to Cyprus

and Singapore, and rose to the rank of colonel. He died of cancer, aged 49 in

1897.

We left Rourke’s Drift with the sun setting, lots to talk about as we headed to our

digs.

ALL IN ALL SO PLEASED TO HAVE

BEEN TO THIS HISTORIC SITE

A SCHOOLBOY DREAM COME

TRUE |