Chums Go Through

|

Panama Canal - Transit Procedures For Chums

We arrived at the Visitor’s Centre, Miraflores Lock and made a bee-line for the observation deck at the top of the building. I was the child in the proverbial sweet shop as Zenit made her approach. This container ship was built in 1998 and was on her way to Buenaventura in Colombia. She is five hundred and eighty four feet long and nearly ninety two feet wide. She can bimble along at fifteen knots and has a deadweight tonnage of just over twenty five thousand. She carries the Marshall Island flag and her call sign is V7KP8.

In came Clipper Kasashio enjoyed by us, as Zenit went down and through. General cargo ship Clipper Kasashio was built in 2008 and was on her way to Ecuador, she’s just over five hundred and eighty feet long, just over ninety five feet wide, she flies the Panamanian flag, her call sign is 3FZH4 and her deadweight is thirty two thousand, two hundred and twenty one tons. She happily bimbles along at thirteen and a half knots.

Down and through she went with crew and passengers waving enthusiastically, taking photographs of the onlookers taking photographs of them.

There are many different parts of the Panama Canal that all work together. There are three locks in the Panama Canal, Gatun, Pedro Miguel and Miraflores. A ship entering the Canal from the Atlantic Ocean to the Pacific Ocean enters at Gatun Locks and exits at Miraflores Locks. While going through the Panama Canal, the ship will be raised and lowered eighty-five feet. After going through Gatun Lake and Gaillard Cut, the ship enters Pedro Miguel Locks and is lowered thirty one feet.

After Pedro Miguel Locks, one mile later it enters Miraflores Locks to be lowered the remaining fifty four feet to the Pacific Ocean. The locks are one hundred and ten feet wide, one thousand feet long and eight stories high. Each time a ship goes through (a lockage), fifty two million gallons of water are used. There are three lock chambers in every lock station. It usually takes a whole day (eight to ten hours) to transit the canal from one ocean to the other, although a vessel may anchor in the canal waters, waiting to transit the canal, from a few hours to a few days. A ship from the Atlantic Ocean enters the Panama Canal waters of Limon Bay from the breakwater at Cristobal. Upon arrival in Panama Canal waters, if a vessel is not scheduled to transit that day, it will drop anchor and wait for its scheduled transit time. Otherwise, the vessel will sail toward the first lock. The Panama pilots take control of the vessel during its transit through Panama Canal waters. The chief pilot will instruct the ship's captain as to the speed and direction of the vessel. The chief pilot also will tell the tug operators, line-handlers and locomotive engineers what assistance they need to provide, while the pilot remains in contact with the Panama Canal TCC and each lock tower. The captain relays the pilot's instructions to his crew members, who perform the proper manoeuver.

Views from the bridge

As the vessel approaches the first set of locks, another launch boat delivers linehandlers to the ship. The line-handlers board the vessel and prepare to receive the cables, attached to each locomotive, that pull the vessel through each lock chamber. A Panamax vessel requires twenty line-handlers (to Beez four), twelve locomotives (six at the bow and six at the stern, three to port and three to starboard), and one tug pushing from the stern to assist the vessel through each lock. One pilot will remain on the bridge at all times, moving between the wheel room and to either wing bridge to call out instructions, "full ahead," "rudder ten degrees," "ahead one-third," "midships," etc. The other pilot will move about the vessel from bow to stern, port to starboard, keeping watch on the ship's progress throughout the canal transit. The vessel steams six and a half miles under tug assistance to the Gatun Locks, the first set of locks. Three "steps" at Gatun Locks, individual chambers into which ships are manoeuvered, raise the vessel the eighty-five feet to Gatun Lake. This first set of locks is about one and a quarter miles long. At the first lock, Gatun Lock, the chief pilot will have the captain's crew maneuver the vessel to the approach wall, where the line-handlers attach the cables of the locomotives to the vessel. The pilot continues calling out maneuvers to the captain, and the vessel continues forward with assistance from the tug at the stern. When the vessel reaches the first chamber of the lock, linehandlers will attach the cables of the remaining locomotives to the vessel and draw them tight to stabilise the vessel for entry into the chamber. Together with the locomotives and tugs and under its own power, the vessel moves into the first chamber, where miter gates close behind the vessel's stern to lock it into the chamber. Water from the second chamber flows into the first chamber and lifts the vessel to the water level of the second chamber. Once the vessel has stopped rising, the miter gates at the vessel's bow open, and the vessel moves forward into the second chamber with assistance from the locomotives and under its own power. The process repeats for the second chamber. In the last chamber, the vessel is lifted to the level of Gatun Lake. In each chamber lockage, raising a vessel requires about fifteen minutes, and each lock transit will last from forty five minutes to more than an hour. Transit time, however, will vary with daily vessel traffic. Once the miter gates of the last chamber open and the vessel has cleared the gates, the cables from each locomotive are released, and the vessel steams through the tropical waters of Gatun Lake under its own power the twenty three and half miles from the Gatun locks to the Gaillard Cut. The water in Gatun Lake pushes ships through the lock chambers, using two hundred and one million liters of water for each ship transit. The Gaillard Cut traverses seven point eight miles through the Continental Divide of Panama at the highest point of the isthmus. Before construction of the canal, the cut was more than four hundred and three feet above sea level and just under three hundred feet wide. One portion was widened to four hundred and ninety nine feet during the 1930's and 1940's, and the remaining portions were completed by 1971. Starting in the 1990’s the cut was widened to six hundred and thirty feet in the straight sections and seven hundred and thirty one feet at the curves to allow double passage of Panamax vessels. Panamax ships were limited to single passage through the canal until the widening project was complete. The PCC conducted tests in May 1999 to determine the safety of a double passage of Panamax vessels and measure vessel performance. In June 1999, double passage of Panamax vessels began. The widening of the cut was finished by 2002 and increased transit capacity by about twenty percent. Once past the Gaillard Cut, the vessels encounter the first of two locks that will lower the vessel to the level of the Pacific Ocean. The first lock, Pedro Miguel, has one chamber, point eight of a mile long, which will lower the vessel twenty eight feet. From Pedro Miguel, the vessel sails into Lake Miraflores and proceeds about one point two miles to the Miraflores Locks, whose two chambers lower the vessel to sea level. From the Miraflores Locks, the vessel moves toward the Pacific Ocean under the Bridge of the Americas, where the pilot returns the vessel to the captain and boards the launch boat.

What the controller sees from his desk.

Panama Canal – Panamax: The Panama Canal was designed and built to accommodate the World War I battleships, Arizona and Pennsylvania. These vessels were one hundred and six feet in beam and had drafts of thirty four feet with displacements of thirty four thousand tons. By comparison, during World War II, larger military vessels, battleships and aircraft carriers with beams of up to one hundred and eight feet, drafts of thirty eight feet, and displacements of fifty three thousand tons transited the Canal. These World War II vessels barely fit the one hundred and ten-foot-wide lock chambers with less than twelve inches between the ship's sides and the concrete lock walls. For instance, the fourth Missouri (BB-63), the last battleship completed by the USA, was laid down on the 6th of January 1941 by New York Naval Shipyard and launched on the 29th of January 1944. After trials off New York and shakedown and battle practice in Chesapeake Bay, Missouri departed Norfolk on the 11th of November 1944, transited the Panama Canal on the 18th of November 1944 and steamed to San Francisco for final fitting out as fleet flagship. Ships of this class had a Full Displacement of fifty seven thousand, two hundred and seventy one tons, an Overall Length of eight hundred and eighty eight feet, an Extreme Beam of one hundred and nine feet and a Waterline Beam of one hundred and eight feet, with a Maximum Navigational Draft of thirty eight feet.

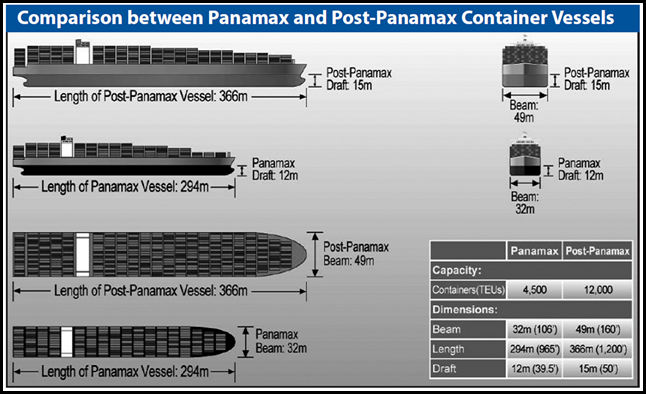

The successful transiting of these vessels set precedence for the passage of the larger commercial vessels of today. Known as Panamax, these vessels have displacements of over seventy thousand tons, which is more than double the size of the designed lock capacity. The largest ship capable of transiting the canal is called a "Panamax." The size of a ship transiting the canal is limited by the size of each lock chamber. Vessels must measure less than one hundred and five feet at the beam (width), nine hundred and fifty six feet in length for containerships and nine hundred and ninety one feet in length for other commercial vessels, and thirty nine feet in draft [the portion of the vessel submerged below the water line].

Ships too large to transit the canal are called "post-Panamax." Transits of Panamax vessels are increasing, representing one-fifth of all transits in 1983 and one-quarter of all transits in 1988. By the mid-1990’s, one out of every three ships was a Panamax transit. The average size of a ship in the world oceangoing fleet is increasing and more ships are being built as post-Panamax vessels. During the 1980's, about ninety two percent of the world cargo fleet could use the Panama Canal, but by 2000, it was estimated that only eighty two percent were able to use it. Panamax-size ships make a more effective transit through the canal by carrying more cargo, but they diminish the efficiency of the canal because they are limited, by canal policy, to daylight transits, require extra pilots and line handlers, take longer to traverse a set of locks, and are restricted to single passage through the narrowest portions of the canal in the Gaillard Cut. In fact, the lockage of a laden Panamax vessel requires forty percent more time than a vessel with a beam under ninety eight and a half feet because the narrowest passageways through the Gaillard Cut prevent the largest vessels from safely passing one another. Water will not compress. It takes an enormous amount of energy to force the oversized Panamax vessel into a lock chamber. In order for a pilot to get a Panamax into a lock chamber, the vessel's engines must be placed at full speed ahead (now that is amazing) and the electric locomotives operated at maximum towing capacity. In some cases tugboats are directed to assist with the lockage by pushing on the stern of the vessel. Each time a Panamax vessel is forced into a lock chamber, the whole structure begins to vibrate. Cracks can be observed in the concrete lock walls, and the steel miter gates leak. Most vessels now built for the world's container fleet are too large for the canal. These larger vessels are built to carry more containers and make fewer port calls. In practical terms, larger ships mean the operating costs of a vessel can be distributed across more containers. These larger ships, however, require ports with deeper drafts and more shoreside services, and are in port longer to unload and load-back containers. As such, these ships are scheduled to call on fewer ports and use alternative inland modes to transport containers to final position, rather than transit through the Panama Canal.

ALL IN ALL AWESOME |