Denniston Incline

|

The Denniston

Incline

Yesterday

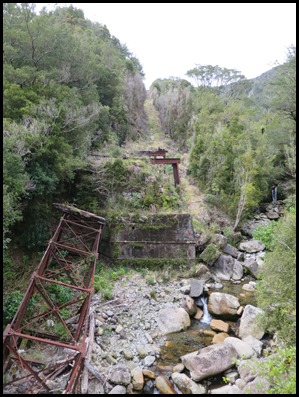

we met the ruins of the Denniston Incline. After our tour of the mine with Liz

we bimbled around the site amongst the scattered relics of the past. From a high

vantage point it seemed as if we were looking at the end of

the line, when we walked as far as we dare over the edge and looked back,

we could see the beginning of what has been described

in its heyday, as the Eighth Wonder of the Industrial World.

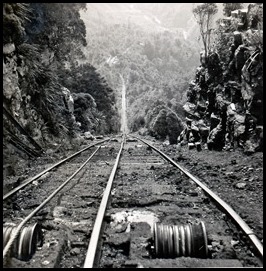

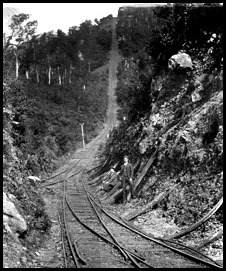

We saw these pictures on the

information boards at the top by the mine. The Incline seen

from the start and from the bottom. After our

drive around the ghost town of Denniston we drove down the hill to find the end

of the Incline.

We drove off the main road and

followed the gravel. As we got closer we could just make out the line on the hill – left of

centre. After parking Mabel we really had to zoom in to show the

Incline in any detail. We could just make out the wagon

- seen as a tiny black dot.

Mining of the high-grade bituminous

coal was made possible by the construction of the Incline Railway in 1879, it

brought coal down from the plateau. The system was conceived by R. B. Denniston, the manager

of the mine, after whom the settlement was named. Between 1879 and 1967 the

Incline brought down more than thirteen million tonnes of coal.

The Denniston Incline was a steeply graded

incline

railway

that connected Denniston at the top with the Conns Creek

Branch.

The incline fell one thousand, six hundred and seventy three feet in five

thousand, five hundred and seventy seven feet or in new money, 510 meters in 1.7

kilometres, with some sections having gradients over 1 in 1.3. The

track was the standard NZR track gauge of three feet six inches and the system

was designed to supply coal ships at Westport.

The wagons used on the Incline were the ubiquitous “Q” class hopper wagons that could be detached from their wagon bodies and lifted by wharf crane over the hold of a ship, and the bottom discharge doors of the wagons opened manually to let the coal fall into the ships' holds. Plenty of dents can be seen made by the encouraging taps from the crowbars of many a loader.

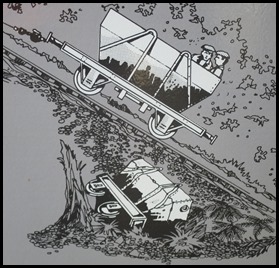

The 'Incline' was actually two inclines. The higher of the two began at Denniston, and descended steeply to the appropriately named "Middle Brake". Here wagons were disconnected from the first incline's rope, and placed on the rope of the second incline for a more gentle descent to Conns Creek, where the accumulated wagons would then be marshalled into trains to be taken to Westport on the hour, every hour. The Denniston Incline worked by gravity: the descending loaded wagons of coal pulled up the empty wagons. The braking system of the winding drums used hydraulic pistons to slow the rotation of the drums. The drum from Middle Brake, is on display at Westport's Coaltown Museum. The ascending side was known as the "Donkey Side", the descending side was the "Company Side". Every second trip wagons swapped sides and always crossed at the same point. The top half and steepest part of the Incline took a wagon two minutes to descend, the larger but gentler lower section took two and a half minutes. The Halfway Stage brakeman controlled the wagons, he heard the bell at the bottom meaning an empty was ready to begin the journey up from Conns Creek so he eased the brake, that began the journey of the full wagon from the top.

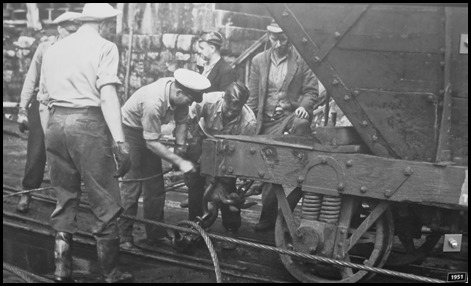

The men at the top and bottom worked as a team in all weathers to connect the wagons to the Incline wire. Many a finger was lost. In the bitter winters the men would defrost their numb fingers by soaking them in a bucket of hot water.

Brakemen: Specialists in a highly responsible

job, they operated the hydraulic brakes, extra brakemen loaded

wagons.

Donkeyman: Operated the brakehead donkey winch that

pulled empty wagons up a slight grade from the bins so they could be gravity-run

back down to the loading area.

Hookmen: Hooked and unhooked the main rope, tallied

wagons at Conns Creek and signalled when the wagons were ready to be pulled

up.

Rope Pullers: Pulled the rope clear as empty wagons

came over the brow of the hill. They prepared the hook and rope for the next

wagon. They eased the weight of the full wagon onto the main rope with the

‘Sampson’ cable

Roadmen: Walked the

tracks checking for faults, oiled rollers and shovelled coal from the rails.

They put in shorter rails as the track crept

downhill.

Ganger: Was in charge of

roadmen and organised work to be done on the Incline.

Trimmer: Trimmed coal to back of the wagon to prevent spillages and helped with the blocks. Foreman: Continuously checked Incline from top to bottom and inspected the ropes and splices. Wagon Examiner: Checked wagon brake and repaired where necessary. Bows Man: Attached the large, hook-like ‘bows’ which fitted between the wagon and brake cable. Runner-Out: Gravity-ran wagons to the end of the yards for the train to pick up..

Although illegal to do so, in the early days the only means of access to Denniston was via the perilous journey up the Incline in one of the Q wagons. In 1882 a description of a ride up Incline from the Westport appeared in the Times and Star:- There were two women in our truck and when we started they were seated near the front end. We were going up over the trestle work – the viaduct, when the ladies began to slide back towards the back of the truck. Their screams could be heard a mile away.......” Many womenfolk said the journey up was the only one they would take and never came down again “until they were carried down in their box”. Going down people had to perch on the ledge of the chassis and hold on tight to the edge of the hopper. Report from the School Inspector in 1882. “.........I inspected this school in April, but do not care to entrust my life a second time to a wire rope that had given way shortly before my visit to the West Coast. When a safe and practicable road is made to this school I hope to revisit it....”

The Incline was the only way furniture and supplies got to the top until the road was built in 1902. A report from Inspector Binns to Undersecretary of Mines, 1883 said “Last year I remarked on the dangerous practice of riding on the trucks up and down the Incline. It is morally certain that if this continues, somebody will be killed. There have been many accidents to the wagons and some hair-breath escapes to passengers. The difficulty stopping it is that no proper road exists.” Max Higgins left school at fifteen and became an apprentice fitter and turner. Over the years of working for the company he spent many hours repairing the Incline, but the Incline did not stop during working hours. Max once spent a day squatting beside a faulty bearing, pouring on castor oil between each wagon as it raced past. Castor oil was thinner than engine oil and kept the bearing cool until it could be replaced that evening. Saturdays were set aside for major repair work. Bill Bryce in one such ‘incident’ said at the time:- “.....the hopper jumped out of the chassis of the empty wagon and rolled down the Incline........the chassis turned upside down across the rails.......the chassis broke loose...... there were just two streaks of flame from the rails....it hit the full wagon on the bridge. The full wagon ran through middle brake, through the front of the cabin....hit the winch house, landed upside down in the ditch....”

The two inclines were single line operation with passing loops, where the empty and full wagons crossed. Collisions were not unknown: the remains of several wrecked wagons still lie beside the incline formation.

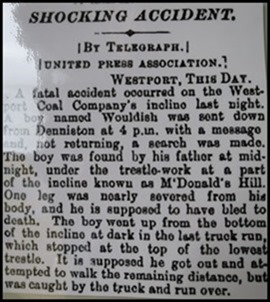

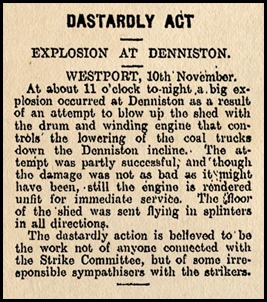

A number of workers and people travelling on the incline died as a result of collisions and runaways. It was also a target for ‘a dastardly action’.

This 1944 picture of a school group

having a nature study lesson beside the Incline, shows just how steep it was. A

coal truck is seen whizzing past, the fruit for their fathers’

labour.

The skipway which had been used to convey coal from the mines to Denniston since the early days of the Denniston Incline, was replaced in 1952 with an aerial ropeway. By the 1960’s the writing was on the wall for the Denniston Incline and the decision was taken to close it by 1969, the actual last day of operation being on the 16th of August 1967. The Conns Creek branch which connected to the foot of the incline was cut back to a siding about one mile long where the coal was loaded from trucks. A few months later the aerial ropeway from the mines also closed down in favour of direct trucking of coal from the mine to Waimangaroa. In May 1968 the Inangahua earthquake caused much damage to the incline, making the closure irreversible. With declining coal markets, and the fact the system was almost entirely reliant on the outdated "Q Class Wagons", it was seen to be more cost effective to truck any remaining coal from the plateau down the hill via the public road, rather than rebuild the Incline. Thus what was once described as the "Eighth Wonder of the World" by locals, faded into history. The closure of the Incline didn’t necessarily mean the end of mining, applications to mine began in 2010. Various court dates were filled with applications and appeals. In March 2012, a crowd of environmental activists and Green Party MPs rallying against coal mining greeted Prime Minister John Key Energy and Resources Minister Phil Heatley with boos and jeers as they attended the opening of Bathurst Resources’ new Wellington offices. As of July this year Bathurst Resources are mining on the Denniston Plateau. The company will have to submit a new application every year for permission to continue to mine. The company paid a twenty two million compensation schedule covering seven years, the Department of Conservation will use the money towards pest and predator control in the Kahurangi National Park and the Denniston Plateau. There are groups opposed to the open cast mining on Denniston but today we watched the big lorries on their way down filled with ‘black gold’.

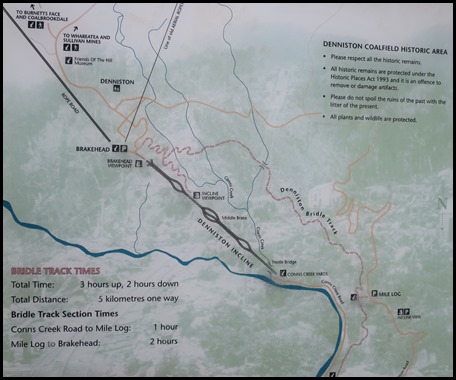

We walked up the track as far as we could, there we looked down on the ruins of the first of the two bridges. The view back down to Mabel, bits of four inch wire littering the way, a variety of nuts and bolts, even the odd lump of coal. We had no plans to spend three hours walking up the nearby bridle path as we wanted to explore the remains of the aerial system further up the road at Stockton.

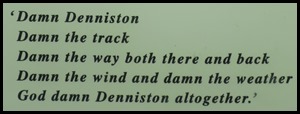

Blasted, picked and shovelled out of the steep hillside, the bridle track was opened in 1884. It was a great asset for people who no longer had to trudge up and down the Incline, with the added worry of being struck by a railway wagon. Perhaps the only citizens with some reservations about the track were the school pupils, for the inspector could now resume his visits. People grew to dislike the track as well. The piece of ‘verse’ by some anonymous traveller was no doubt repeated by others to pace their upward plod is all conditions. For newcomers to Denniston the last but hardest part of the journey began here. Leaving their precious possessions to be carried up in a wagon, hoping it would not break free and destroy them. If not too fatigued they might discover as a traveller in 1891 did, that “the journey up, though trying to most people, affords magnificent views of the surrounding country and of the sea beyond.”

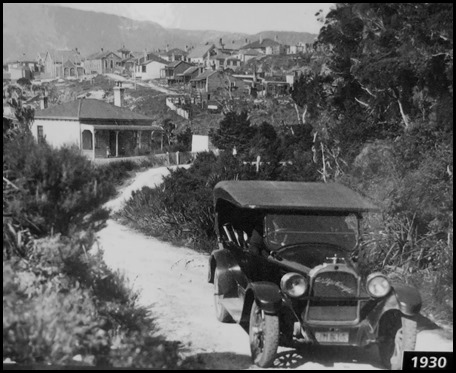

For those who lived ‘on the hill’, completion of the ‘new track’ – vehicle road in 1902 was a great occasion. Development of transport led to the decline of the towns on top of the plateau, as workers could live down near the sea and commute up to the mines daily. By the late 1920’s cars were seen in Denniston.

Amazing Incline Factoids:- An average of a hundred wagons ‘went over’ the top of the Incline every day or one every four minutes. A thousand tons of coal came down every day or one hundred and twenty tons an hour. On a ‘normal working day’. Fifty two men – fourteen miners and sixteen Incline men, moved coal down from Denniston, twenty two railwaymen delivered the coal to the awaiting ship. From coal face to ship took just six and a half hours. The steam cranes of Westport loaded the ships and up until 1954 they were the busiest cranes on the west coast. Quite something. The Incline’s remains and the formidable community of the Denniston Plateau slowly diminished over time following the closure of the Incline in 1968, the relics of the past are slowly disappearing.

ALL IN ALL IN ITS TIME, AN INCREDIBLE PIECE OF ENGINEERING MOST EXTRAORDINARY FOR ITS AGE |