Amazing

|

Our Wonderful Encounter with a Humpback Whale and her Calf

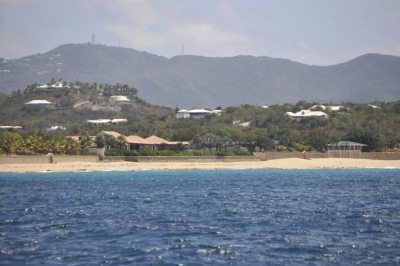

We had left St Martin and I got these shots of the beaches we had visited the day before

Last shots of St Martin, sails up and settled into a pleasant sixteen mile journey to St Barts and another couple of ticks in the 1000 Places book

Humpback whales make a seasonal migration - some two thousand miles - between their summer feeding grounds off New England and Canada to the tropical waters off the Caribbean in winter. Attracted to the shallow, protected waters of St. Vincent and the Grenadines coming here from January to May to mate and have their calves. Sitting minding my own business, halfway through swallowing some lemonade, I saw something big “jump” in the water, a fair way off, over Bears right shoulder. I started frantically gesticulating, at first Bear thought I was asking for a Heimlich Manoeuvre. Leaping for the camera we both watched the most spectacular dance with a mum teaching her calf to breach five miles south of Phillipsburg, Sint Maarten (the Dutch side of St Martin). The first shot - and sadly the closest she came to us - was taken from my best vantage point, I clicked as I fell down the top two steps into Beez, hence blurred.

We watched in silent awe.

The humpback whale (Megaptera novaeangliae) is a baleen whale. One of the larger rorqual species, adults range in length from thirty nine to fifty two feet and weigh thirty six to forty tons. The humpback has a distinctive body shape, with unusually long pectoral fins and a knobbly head. It is an acrobatic animal, often breaching and slapping the water. Males produce a complex whale song, which lasts for 10 to 20 minutes and is repeated for hours at a time. The purpose of the song is not yet clear, although it appears to have a role in mating. Found in oceans and seas around the world, humpback whales typically migrate up to twenty five thousand kilometres each year. Humpbacks feed only in summer, in polar waters and migrate to tropical or sub-tropical waters to breed and give birth in the winter. During the winter, humpbacks fast and live off their fat reserves. The species' diet consists mostly of krill and small fish. Humpbacks have a diverse repertoire of feeding methods, including the bubble net feeding technique. Like other large whales, the humpback was and is a target for the whaling industry. Due to over-hunting, its population fell by an estimated 90% before a whaling moratorium was introduced in 1966. Stocks have since partially recovered; however, entanglement in fishing gear, collisions with ships and noise pollution also remain concerns. There are at least eighty thousand humpback whales worldwide.

The

humpback whale was first identified as "baleine de la Nouvelle Angleterre" by

Mathurin

Jacques Brisson

in his Regnum

Animale

of 1756. Humpback whales can easily be identified by their stocky bodies with

obvious humps and black dorsal

colouring. The head and lower jaw are covered with knobs called tubercles,

which are actually hair

follicles

and are characteristic of the species. The fluked tails, which it lifts above

the surface in some dive sequences, have wavy trailing edges. There are four

global populations, all under study. North Pacific, Atlantic and southern ocean

humpbacks have distinct populations which complete a migratory round-trip each

year. The Indian Ocean population does not migrate, stopped by that ocean's

northern coastline. The long black and white tail fin, which can be up to a third of body length, and the pectoral fins have unique patterns, which make individual whales identifiable. Several hypotheses attempt to explain the humpback's pectoral fins, which are proportionally the longest fins of any cetacean. The two most enduring mention the higher maneuverability afforded by long fins, and the usefulness of the increased surface area for temperature control when migrating between warm and cold climates. Humpbacks also have 'rete mirable' a heat exchanging system, which works similarly in sharks and other fish. Humpbacks have two hundred and seventy to four hundred darkly coloured baleen plates on each side of the mouth. The plates measure from eighteen inches in the front to approximately three feet long in the back, behind the hinge. Ventral grooves run from the lower jaw to the umbilicus about halfway along the bottom of the whale. These grooves are less numerous - usually sixteen to twenty and consequently more prominent than in other rorquals. The stubby dorsal fin is visible soon after the blow when the whale surfaces, but disappears by the time the flukes emerge. Humpbacks have a ten foot heart-shaped to bushy blow, or exhalation of water through the blowholes.

Newborn

calves are roughly the length of their mother's head, arriving tail first. A

fifty foot mother's calf arrives measuring about twenty feet weighing in at two

tons. They nurse for approximately six months then mix nursing and independent

feeding for another six months. Humpback milk is fifty per cent fat and pink in

colour. Some calves have been observed alone after arrival in Alaskan

waters. Females

reach sexual maturity at the age of five achieving full adult size a little

later. Males reach sexual maturity at approximately seven years of age. Whale

lifespan estimates range from thirty to eighty years. Fully

grown the males average forty nine to fifty two feet. Females are slightly

larger at fifty two to fifty six feet, and about forty four tons; the

largest humpback, according to whaling records, was killed in the Caribbean. She

was eighty eight feet long, weighing nearly ninety tons. Females

have a hemispherical lobe about

six inches in diameter in their genital region. This visually distinguishes

males and females. The male's penis usually remains hidden in the genital slit.

Male whales have distinctive scars on heads and bodies, some resulting from

battles over females. Identifying

individuals The varying patterns on the tail flukes are sufficient to identify individuals. Unique visual identification is not currently possible in most cetacean species (other exceptions include orcas), making the humpback a popular study species. A study using data from 1973 to 1998 on whales in the North Atlantic gave researchers detailed information on gestation times, growth rates, and calving periods, as well as allowing more accurate population predictions by simulating the mark-release-recapture technique. A photographic catalogue of all known North Atlantic whales was developed over this period and is currently maintained by Wheelock College. Similar photographic identification projects have begun in the North Pacific by SPLASH (Structure of Populations, Levels of Abundance and Status of Humpbacks), and around the world. Another organization (Cascadia Research) headed by well-known researcher John Calambokidis, along with Dr. Robin Baird, joined with others from NOAA, hoping to prepare a public online catalog of more than 3500 fluke identification pictures.

Life

history Reproduction:

Females

typically breed every two or three years, occasionally each year, the gestation

period is eleven and a half months. Humpback whales were thought to live fifty

or sixty years, but new studies using the changes in amino acids behind eye

lenses proved another baleen whale, the bowhead,

to be two hundred and eleven years old. Recent research on humpback mitochondrial

DNA

reveals that groups that live in proximity to each other may represent distinct

breeding pools. Social structure: Humpbacks frequently breach, throwing two thirds or more of their bodies out of the water and splashing down on their backs. The humpback social structure is loose-knit. Typically, individuals live alone or in small, transient groups that disband after a few hours. Groups may stay together a little longer in summer to forage and feed cooperatively. Longer-term relationships between pairs or small groups, lasting months or even years, have rarely been observed. It is possible that some females retain bonds created via cooperative feeding for a lifetime. The humpback's range overlaps considerably with other whale and dolphin species however they rarely interact socially with them.

Courtship:

Courtship

rituals take place during the winter months, following migration toward the

equator from summer feeding grounds closer to the poles. Competition is usually

fierce, and unrelated males dubbed escorts by researcher Louis

Herman

frequently trail females as well as mother-calf dyads. Groups of two to twenty

males gather around a single female and exhibit a variety of behaviours over

several hours to establish dominance of what is known as a competitive group. Group size ebbs

and flows as unsuccessful males retreat and others arrive to try their luck.

Behaviour includes breaching, spy-hopping, lob-tailing,

tail-slapping,

fin-slapping, peduncle

throws,

charging and parrying. Less common "super pods" may number more than forty

males, all vying for the same female. Song:

Both

male and female humpback whales vocalise, however only males produce

the long, loud, complex "songs" for which the species is famous. Each song

consists of several sounds in a low register

that vary in amplitude

and frequency,

typically lasting from ten to twenty minutes. Humpbacks may sing continuously

for more than twenty four hours. Cetaceans

have no vocal cords, so whales generate their song by forcing air through their

massive nasal cavities. Whales within a large area sing the same song. All North

Atlantic humpbacks sing the same song, and those of the North Pacific sing a

different song. Each population's song changes slowly over a period of years

without repeating] Scientists are unsure of the purpose of whale song. Only males sing, suggesting that one purpose is to attract females. However, many of the whales observed to approach a singer are other males, and results in conflict. Singing may therefore be a challenge to other males. Some scientists have hypothesized that the song may serve an echolocative function. During the feeding season, humpbacks make altogether different vocalisations for herding fish into their bubble nets.

Time for the baby to try his first breach but only a tiny splash and then they were gone, ending our private view of their world Feeding:

Humpbacks

feed primarily in summer and live off fat reserves during winter. They feed only

rarely and opportunistically in their wintering waters. The humpback is an

energetic hunter, taking krill and small schooling fish,

such as herring,

salmon,

capelin

and sand

lance

as well as mackerel,

pollock

and haddock

in the North Atlantic. Krill and copepods

have been recorded from Australian and Antarctic waters. Humpbacks hunt by

direct attack or by stunning prey by hitting the water with pectoral fins or

flukes. Bubble net feeding: a group of humpbacks swim in a shrinking circle blowing bubbles below a school of prey. The shrinking ring of bubbles encircles the school and confines it in an ever-smaller cylinder. The whales then suddenly swim upward through the 'net', mouths agape, swallowing thousands of fish in one gulp. This ring can begin at up to a hundred feet in diameter via the cooperation of a dozen animals. Using crittercam attached to whale's back it was discovered that some whales blow the bubbles, some dive deeper to drive fish toward the surface, and others herd prey into the net by vocalizing. Humpbacks have been observed bubble net feeding alone as well.

ALL

IN ALL THE MOST INCREDIBLE SIGHT WE HAVE EVER SEEN

TRULY

SPECTACULOR |