Life at the Fort

Beez Neez now Chy Whella

Big Bear and Pepe Millard

Thu 24 Feb 2011 23:59

|

The

Citadel

After taking in the spectacular views eight hundred feet up, we crossed the

dry moat and into the Citadel

Once inside we found most of the rooms

restored, labeled as to what they would have been used for and laid out with loads of interesting information

Management and Maintenance of

the Fortress: During its greatest use during the Napoleonic Wars

(1792-1815), the Fortress was occupied by nearly 1000 soldiers (both white line

regiments and Africans of the West India Regiments), 200 wives and children of

officers, a dozen members of the civil staff as well as 100 or more African

slave workers. The top of the hill and its upper slopes were crowded with

buildings, huts, ramparts and batteries giving it the appearance of a small hill town. Such a community had to be

supplied with food, water, equipment and clothing - and the buildings had to be

repaired and new ones constructed. This was managed by a small team known as the

Respective Officers", usually consisting of the chief officers of Engineers and

Artillery and the storekeeper.

Regiments were recruited to the "beat

of a drum". The poor, the desperate, or those seeking adventure joined up.

Others were convicted criminals escaping punishment or imprisonment by agreeing

to join up. Only six wives per hundred men posted were allowed. This left many

wives and families behind to become destitute. The first stage in the journey to

St Christopher was a long voyage in a troop ship across the Atlantic Ocean. Some

soldiers died of ill health along the way. On arrival, the welcome appearance of

land - of an Eden-like landscape - gave way to the reality of uncomfortable

quarters, boredom and the ever-present threat of disease. Recruits received

little training and may only rudimentary steps of drill. They had to learn

soldiering on the job.

The 15th

East Yorkshire Regiment (The Snappers): The Regiment was raised

in 1685 as the 15th Regiment of Foot and saw early service in Scotland and

Flanders. In 1702 it formed part of the Duke of Marlborough's army and took a

prominent position in many battles including Blenheim and Ramilies. During the

Seven Years' War the Regiment took the fortress of Louisburg (1758) and was

present at Quebec (1759) when General Wolfe was killed. Further campaigns

followed in Martinique and the American War of Independence (1776-1778) during

this time the Regiment gained the nickname "The Snappers". The Regiment was

represented at Brimstone Hill in 1779 and again in 1782 when, in combination

with soldiers of the Royal Scots Regiment and 350 of the local Militia -

totaling less than a thousand men they held off the French for a month, but

eight thousand enemy soldiers saw them surrender with full military honours. The

Regiment served again at Brimstone Hill (but saw no action) during

1812-1815.

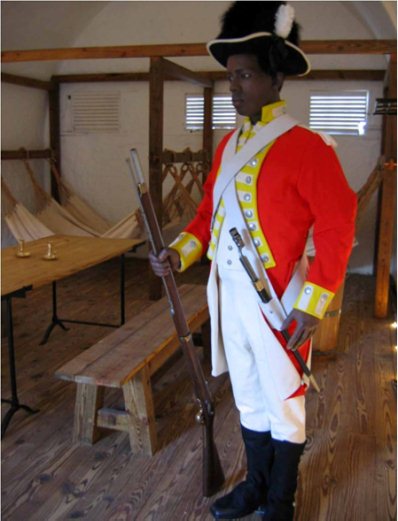

West

Indian Regiments - 'Africans in Redcoats': To overcome the

manpower and health problems among the European forces which diminished their

numbers considerably in the Caribbean, African slaves were purchased in Africa,

captured from slave ships or recruited from the plantations to serve in the

British Army. In 1795, the British established the first two black regiments,

commanded by British officers. Twelve such regiments were raised, but the

numbers fluctuated. They served British military interests in the Caribbean

(where they were awarded three Battle Honours) and also in West Africa.

Detachments of West India Regiments

(WIR) were stationed at Brimstone Hill from time to time, including the 4th WIR

in the mid 1790's and the 2nd WIR in 1851.

Soldiers of the WIR were equal to

white soldiers of other regiments, but West Indian plantation oligarchies did

not recognise such freedoms when a black soldier was discharged. They were

indeed opposed to their recruitment in the first place. Thus, in St Kitts in

1797, the local House of Assembly used a "trifling" disturbance among a few of

the 250 WIR soldiers garrisoned at Brimstone Hill (who became alarmed at a

rumour that they would be discharged and enslaved) to prevail upon the colonial

authorities to transfer the regiment to St Vincent.

The last WIR was disbanded in

1927.

Slavery at Brimstone

Hill: Physical exertion under the tropical sun was considered injurious

to the health of Europeans. Instead, workers enslaved from Africa were used. The

building, expansion and maintenance of the Fortress on Brimstone Hill depended

not only on their labour but on their skills. They were miners, stone masons,

brick layers, plasterers, carpenters, coopers, plumbers and cooks. Initial

training in some of these crafts may have been from European specialists but

from this developed an on-going base among the Africans whether working for the

plantations, the Government or at the Fortress.

A Day in the life of a

soldier: In peacetime, daily life of the garrison was a regulated

routine, which left the white troops inside buildings and out of the sun, with

the African slave workers and troops of the West Indian Regiment when in

garrison, undertaking the more arduous duties outside, in fact after breakfast

most English troops lazed around smoking, drinking and playing cards. Breakfast

was a pint of cocoa and a piece of bread. Lunch called "dinner" was a meal

of either fresh (when available) a or salt meat boiled into a soup,

and eaten with yams or potatoes with addition of fruits bought from the local

peddlers. Some bread saved from breakfast might bulk the meal up a bit. From

dinner until breakfast the next day, a period of over eighteen hours, no further

food was provided, except what the individual soldier could provide for himself.

There was also a rum ration which would be supplemented with other bought rum.

This we suppose could be called a liquid diet.

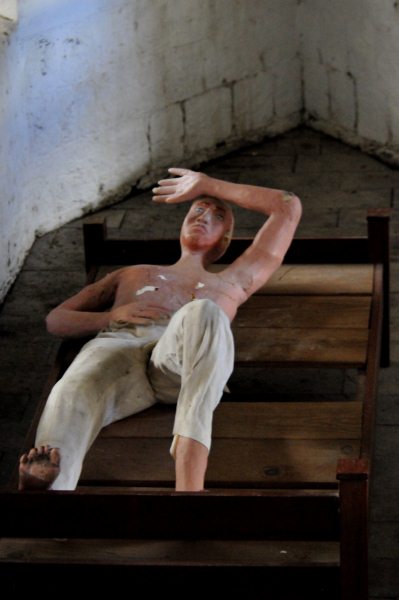

Hospital care was provided at

Brimstone Hill, by a qualified doctor or semi-trained assistants, called

"mates". Doctors knew how to mend broken bones or cut off an arm or leg, but

they were unclear about how to handle disease, whose causes they little

understood. When taken ill and hospitalised,

a soldier was placed on a special diet of milk porridge for breakfast, meat and

bread for lunch and a pint of broth for supper. Madeira wine was sometimes given

to assist recovery but even if it were not, the soldiers sometimes had rum

smuggled to them. Yellow fever and malaria were believed to be spread by an

invisible substance or miasma, floating in the air and resulting from rotting

vegetation or from the swamps. The mosquito was as yet unknown as the means by

which these diseases were transmitted. Civilian staff or military officers who

were debilitated by the effects of disease sometimes asked for a leave of

absence in Britain to get their strength back. They were examined by a medical

Board at Brimstone Hill and if judged incapable of performing their duties, were

sent home. Apart from the twin horrors of yellow fever and malaria, other

conditions suffered by the troops were typhoid, rum poisoning, bowel and eye

infections and sexually transmitted diseases. When yellow fever and malaria

struck, unaffected troops were sometimes segregated from the sick staying out in

tents at the bottom of Brimstone Hill or sent to Basseterre.

Included among the contractors

services was laundering of the bed-linen for the garrison, once every six

weeks.

Disease, Illness and

Death: Many soldiers regarded a posting to the West Indies as a death

sentence - there was a reputation for catching fatal diseases such as

yellow fever and malaria. Death rates were six times greater than in Britain. At

any one time up to a third of the troops might be unfit for service due to

illness. Sedentary life, boredom and the abuse of alcohol may have contributed

to these high rates. Many cases of yellow fever may have been

misdiagnosed alcohol poisoning. African troops of the West Indian Regiment

were more resistant to the diseases which so affected the

Europeans.

Punishment: Minor

offences such as untidiness, loss of military property etc. could be punished

administratively by the Commanding Officer. This might lead to loss of pay.

Drunkenness or fighting among men might be punished by flogging, as well as by

imprisonment. The civilian staff employed in the

garrison could also be disciplined by a panel of officers and if necessary

dismissed from the services. The whirligig, a

spinning cage in which the prisoner was placed and rotated until violently and

physically sick. Good old flogging was used and another punishment was to sit

'On the Horse' - a wooden horse with a pointed saddle. The soldier with hands

tied behind their backs was sat up on the 'pointy bit' and weights were added to

their ankles. Don't, my eyes are watering.

Assault on a senior rank, murder and sex with an animal were crimes that carried

the death sentence.

Religious worship

was an integral part of civil and military life, being seen as the basis for

society itself. In the army this involved practice of Christianity under the

Established Anglican Church. But to the Commander in Chief, religion was as much

about reinforcing a sense of obedience to the authority of the King and his

Officers as it was about safeguarding spiritual well-being of the troops and

their route to heaven. Attendance at Church parade on Sundays was

compulsory.

Meanwhile Bear is

trotting around listening to his lady friend

ALL IN ALL A

FASCINATING INSIGHT

UNUSUALLY DETAILED ACCOUNT OF WHAT IT WAS LIKE TO BE A

SOLDIER HERE

|