Cinchona or Quinine

Tree

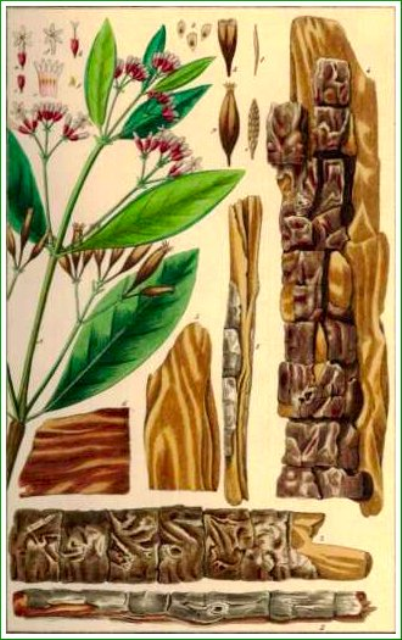

Cinchona is a genus of about 25

species in the family Rubiaceae, native to tropical

South America. They are large

shrubs or small trees growing to 5-15 metres tall with

evergreen foliage. The

leaves are opposite, rounded to lanceolate, 10-40

cms long. The flowers are white, pink or

red, produced in terminal panicles. The fruit is a small capsule containing numerous seeds. South American Indians have been using cinchona bark

to treat fevers for many centuries. Spanish conquerors learned of quinine's

medicinal uses in Peru, at the beginning of the 17th Century. Use of the

powdered " Peruvian bark" was first recorded in religious writings by the

Jesuits in 1633. The Jesuit fathers were the primary exporters and importers of

quinine during this time and the bark became known as " Jesuit bark.". The use

of quinine for fevers was included in medical literature in 1643.

Stories of the medicinal properties of this bark, however, are perhaps

noted in journals as far back as the 1560’s-1570’s. We saw many of these trees

on our 'pram' ride through the rain forest.

Cinchona species are used as food plants by the

larvae of some Lepidoptera species including The Engrailed, The

Commander, and members of the genus

Endoclita including E.

Damor, E. Purpurescens and E. Sericeus.

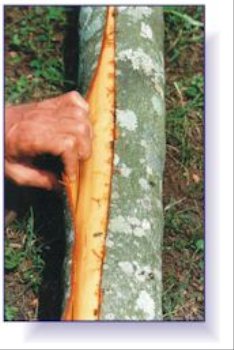

Cinchona alkaloids

The bark of trees in this genus is the source of a variety of

20 alkaloids , the most familiar of which is

quinine, an anti-fever agent especially useful in treating

malaria. Cinchona alkaloids include:

cinchonine and

cinchonidine

(stereoisomers with R = vinyl, R' =

hydrogen), quinine and quinidine (stereoisomers with R = vinyl, R' = methoxy), dihydroquinidine & dihydroquinine (stereoisomers with R = ethyl, R' = methoxy). They find use in organic

chemistry as

organocatalysts in asymmetric

synthesis.

History

The Italian botanist Pietro Castelli wrote a pamphlet noteworthy as being the first Italian

publication that mentions the cinchona. By the 1630's (or 1640's, depending on

the reference), the bark was being exported to Europe. In the late 1640's, the

method of use of the bark was noted in the Schedula Romana, and in 1677

the use of the bark was noted in the London Pharmacopoeia. According to legend,

the first European ever to be cured from malaria fever was the wife of the

Spanish Viceroy, the countess of Chinchon. The

court physician was summoned and urged to save the countess from the waves of

fever and chill that were threatening her life, but every effort failed to

relieve her. At last the physician administered some medicine which he had

obtained from the local Indians, who had been using it for similar syndromes.

The countess survived the malarial attack and reportedly brought the cinchona

bark back with her when she returned to Europe in the 1640s. The story of her

cure is doubtful. Charles II called upon Mr Robert Talbor, who had become

famous for his miraculous malaria cure. Because at that time the bark was in

religious controversy, Talbor gave the king the bitter bark decoction in great

secrecy. The treatment gave the king complete relief from the malaria fever. In

return, he was offered membership of the prestigious Royal College of

Physicians. In 1679 Talbor was called by the King of France, Louis

XIV, whose son was suffering from malaria fever. After a successful

treatment, Talbor was rewarded by the king with 3,000 gold crowns. At the same

time he was given a lifetime pension for this prescription. Talbor, however, was

asked to keep the entire episode secret. After the death of Talbor, the French

king found this formula: six drams of rose leaves, two ounces of lemon juice and

a strong decoction of the chinchona bark served with wine. Wine was used because

some alkaloids of the cinchona bark are not soluble in water, but are soluble in

wine.

The birth of homeopathy was based on

quinine testing. The founder of homeopathy, Dr. Samuel

Hahnemann, when translating the Cullen's

Materia Medica, noticed that Dr

Cullen wrote that quinine cures malaria and can

also produce malaria. Dr. Hahnemann took daily a large non-homeopathic dose of

quinine bark. After two weeks, he said he felt malaria-like symptoms. This idea

of "like cures like" was the starting point of his writings on "Homeopathy". In

1738, Sur l'arbre du quinquina, a paper written by Charles Marie de La

Condamine, a member of the

expedition that was sent to

Peru to determine the length of a degree of the

meridian in the neighbourhood of the

equator, was published by the French Academy of

Sciencies. In it he identified three

separate species. In 1742, on the basis of a specimen received from La

Condamine, Linnaeus named the tree Quinquina condaminiae and established a new

genus, which he termed Cinchona quinquina condaminiae. In 1753 he described

Cinchona officinalis as a separate species.

History of cultivation

The bark was very valuable to Europeans in expanding their

access to and exploitation of resources in far off colonies, and at home. Bark

gathering was often environmentally destructive, destroying huge expanses of

trees for their bark, with difficult conditions for low wages that did not allow

the indigenous bark gatherers to settle debts even upon death. In 1860, a

British expedition to South America led by Clements

Markham brought back Cinchona seeds and plants,

which were planted in the Hakgala Botanical Garden in Sri Lanka in January 1861. James Taylor, the pioneer of tea planting in Sri Lanka, was one of

the pioneers of Cinchona cultivation. By 1883 about 64,000 acres (260

km2) were in cultivation in Sri Lanka, with exports reaching a peak

of 15 million pounds in 1886. In 1865, the "Carlota Colony" was founded in

Mexico. Wealthy American post-war confederate leaders were enticed there by the

Emporer Maximillian, Archduke of Habsburg. The colony was situated on the direct

Mexico-Vera Cruz Highway, and within 50 km. of the railway, which was due to

arrive in Cordoba at the end of that year. ... "All that survives today of the

ill-fated Carlota Colony are the flourishing groves of cinchonas, the

quinine-producing tree which ... at Empress Charlotte's instigation, were first

introduced into the country."

Treatments

Cinchona has been used for a number of medical reasons such as: Treats

malaria (until the development of synthetic drugs, quinine was used as the

primary treatment of malaria, a disease that kills over 100 million people a

year). Kills parasites. Reduces fever. Regulates heartbeat. Calms nerves.

Stimulates digestion. Kills germs. Reduces spasms. Kills insects. Relieves pain.

Kills bacteria and fungi. Dries secretions. Natures own Viagra. The main reason

for its use is to treat malaria, but it is rarely used today as many people

think it is dangerous, as it can kill if taken in large amounts. Quinidine is

used to treat cardiac arrhythmias.

Quinine

Quinine did not gain wide acceptance in the medical community

until Charles II was cured of the ague by a London apothecary at the end

of the 17th century. Quinine was officially recognized in an edition of the

London Pharmacopoeia as "Cortex Peruanus" in 1677. Thus began the quest for

quinine. In 1735, Joseph de Jussieu, a French botanist, accompanied the first

non-Spanish expedition to South America and collected detailed information about

the cinchona trees. Unfortunately, as Jussieu was preparing to return to France,

after 30 years of research, someone stole all his work. Charles Marie de la

Condamine, leader of Jussieu's expedition, tried unsuccessfully to transfer

seedlings to Europe. Information about the cinchona tree and its medicinal bark

was slow to reach Europe. Scientific studies about quinine were first published

by Alexander von Humboldt and Aimé Bonpland in the first part of the 18th

century. The quinine alkaloid was separated from the powdered bark and named

"quinine" in 1820 by two French doctors. The name quinine comes from the

Amerindian word for the cinchona tree, quinaquina, which means "bark of barks."

As European countries continued extensive colonization in Africa, India and

South America, the need for quinine was great, because of malaria. The Dutch and

British cultivated cinchona trees in their East Indian colonies but the quinine

content was very low in those species. A British collector, Charles Ledger,

obtained some seeds of a relatively potent Bolivian species, Cinchona

ledgeriana. England, reluctant to purchase more trees that were possibly low

in quinine content, refused to buy the seeds. The Dutch bought the seeds from

Ledger, planted them in Java, and came to monopolize the world's supply of

quinine for close to 100 years. During World War II, the Japanese took control

of Java. The Dutch took seeds out of Java but had no time to grow new trees to

supply troops stationed in the tropics with quinine. The United States sent a

group of botanists to Columbia to obtain enough quinine to use throughout the

war. In 1944, synthetic quinine was developed by American scientists. Synthetic

quinine proved to be very effective against malaria and had fewer side effects,

and the need for natural quinine subsided. Over the years, the causative

malarial parasite became resistant to synthetic quinine preparations.

Interestingly, the parasites have not developed a full resistance to natural

quinine.

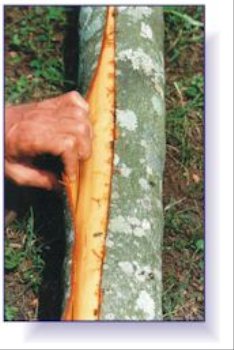

The chemical composition of quinine is

C20H24N2O2.H2O.

Quinine is derived from cinchona bark, and mixed with lime. The bark and lime

mixture is extracted with hot paraffin oil, filtered, and shaken with sulphuric

acid. This solution is neutralized with sodium carbonate. As the solution cools,

quinine sulphate crystallizes out. To obtain pure quinine, the quinine sulphate

is treated with ammonia. Crystalline quinine is a white, extremely bitter

powder. The powdered bark can also be treated with solvents, such as toluene, or

amyl alcohol to extract the quinine. Current biotechnology has developed a

method to produce quinine by culturing plant cells. Grown in test tubes that

contain a special medium that contains absorbent resins, the cells can be

manipulated to release quinine, which is absorbed by the resin and then

extracted. This method has high yields but is extremely expensive and

fragile.

Medicinally, quinine is best known for its treatment of

malaria. Quinine does not cure the disease, but treats the fever and other

related symptoms. Pharmacologically, quinine is toxic to many bacteria and

one-celled organisms, such as yeast and plasmodia. It also has antipyretic

(fever-reducing), analgesic (pain-relieving), and local anaesthetic properties.

Quinine concentrates in the red blood cells and is thought to interfere with the

protein and glucose synthesis of the malaria parasite. With treatment, the

parasites disappear from the blood stream. Many malarial victims have a

recurrence of the disease because quinine does not kill the parasites living

outside the red blood cells. Eventually, the parasites make their way into the

blood stream, and the victim has a relapse. Quinine is also used to treat

myotonic dystrophy (muscle weakness, usually facial) and muscle cramps

associated with early kidney failure. The toxic side effects of quinine, called

Cinchonism, include dizziness, tinnitus (ringing in ears), vision disturbances,

nausea, and vomiting. Extreme effects of excessive quinine use include blindness

and deafness.

Quinine also has non-medicinal uses, such as in preparations

for the treatment of sunburn. It is also used in liqueurs, bitters, and

condiments. The best known non-medicinal use is its addition to tonic water and

soft drinks. The addition of quinine to water dates from the days of British

rule in India-quinine was added to water as a prevention against malaria. About

40% of the quinine produced is used by the food and drug industry, the rest is

used medicinally. In the United States, beverages made with quinine may contain

not more than 83 parts per million cinchona alkaloids.

ALL IN ALL a really useful tree.

|