Syd. Observatory 2

Beez Neez now Chy Whella

Big Bear and Pepe Millard

Fri 19 Feb 2016 23:47

|

Sydney Observatory – Part

Two    Transit of Venus Orrery. In 1760

Benjamin Cole of London built an orrery to demonstrate the transit of Venus.

While not to scale, the orrery shows the relationship between Earth, Venus and

the Sun for the period of the transit. Turning the handle causes Venus to pass

across the face of the Sun, while Earth rotates about its axis. This replica was

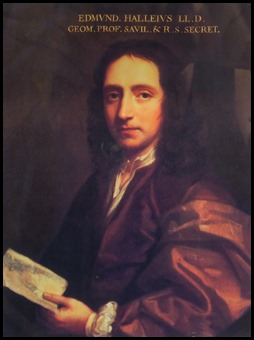

made by orrery maker Brian Greig in 2012. Portrait of Edmond Halley

(1656-1742) published a famous paper in 1716, urging astronomers to ‘diligently’

observe the 1761 transit of Venus. He wrote: “having ascertained with more

exactness the magnitude of the planetary orbits, it may redound to their

immortal fame and glory”. (Painting by Thomas Murray about

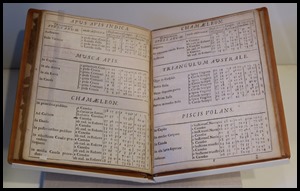

1687) Edmund Halley’s Catalogus Stellarum

Australium. (Catalogue of the Southern Hemisphere Stars) includes

observations of the 1677 transit of Mercury, which he made from the island of St

Helena. The English astronomer published an influential paper in 1716 urging

astronomers to observe the transit of Venus from locations around the world,

arguing that these measurements could be used to calculate the distance of the

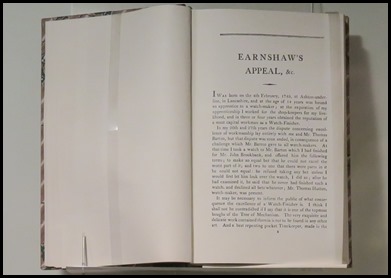

Sun and gauge the size of the solar system.   Longitude – Earnshaw’s Appeal to

the Public. This is a reprint of a book published in 1808 by the English

clockmaker Thomas Earnshaw. Earnshaw was one of the people most closely involved

in the development of the chronometer. Feeling that he had not been adequately

rewarded for his work by the British government, Earnshaw wrote this book. In it

he sets out his claim for the superiority of his chronometers over those of

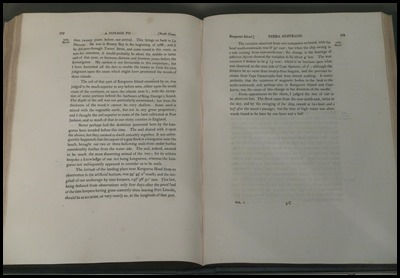

other makers and appeals for better treatment. A Voyage to Terra Australis.

Matthew Flinders wrote up the details of his voyage in two volumes, (one – above

right). In the book he discusses his circumnavigation of the continent in HMS

Investigator, his shipwreck off the coast of Queensland and his nearly seven

year imprisonment on the French island of Mauritius. Sadly Flinders was dying by the time the book was published in

1814 and may not have seen a printed copy. He died on the 19th of July

1814.  Earnshaw 520 Chronometer. This is

one of five chronometers (the box is modern) used by Matthew Flinders who called

it “This excellent timekeeper”. Made by Thomas Earnshaw, it was the only

chronometer still working at the end of the epic three-year voyage. No wonder

Flinders was full of praise for it. Chronometer Clock. A chronometer

has to cope with a ship’s movement and the many climate changes on a long

voyage. Ordinary types of clocks such as those with pendulums would either stop

or run wildly fast or slow. The accuracy of chronometers is due to the design of their

internal mechanism. Thomas Earnshaw developed the final form of this mechanism

in the 1780’s. This modern clock shows the internal workings of an Earnshaw

chronometer.    Mariners

Astrolabe. This is a reproduction of a mariners astrolabe found on the

wreck of the Dutch ship Batavia. The ship hit a reef in 1629 with the eventual

loss of 200 lives. Before Matthew Flinders time, mariners astrolabes were

standard equipment. Flinders Bearing Book. This book is

a copy of the book in which Matthew Flinders recorded his observations of the

Australian coastline. During his voyage Flinders was carrying out a detailed

survey. At each location he first established the position of his ship with the

help of a sextant and chronometers. He then measured the directions or bearings

of any features that he could see. Later he used the information in his bearing

book to draw up a map of Terra Australis or Australia. Sextant. A sextant measures the

angles by which a star or the sun is above the horizon. The angle at any place

depends on both the local time and the latitude – how many degrees north or

south the place is from the equator. By making observations with a sextant,

navigators like Flinders could obtain both the time and the latitude. This

sextant dates from 1787 and would be similar to the one used by

Flinders. Navigators no longer need chronometers, sextants and careful

observations. They can use satellite navigation with the help of Global

Positioning System (GPS) satellites. By picking up signals from three or more

satellites, GPS receivers can work out and display positions to great

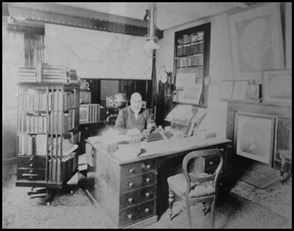

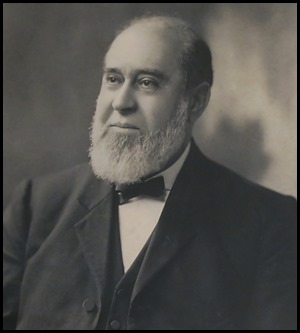

accuracy.    The Star Observer Henry Chamberlain

Russell at his desk. We were standing between the Observatory’s two

domes, which was the office H.C. Russell spent much of his time here reading and

writing about astronomy and meteorology. H.C. Russell pictured in January 1898.

H.C. Russell was the government astronomer at Sydney Observatory, travelled to

the International Astrophotographic Congress in Paris in 1887 on behalf of the

Australian government. Many photographs exist of Henry and his family during

that trip, in the one above you can see the family having fun in shadow of their

ship’s mast and funnel on the sands of Egypt.  Transit Room pictured in the

1870’s. This photograph shows some of the equipment associated with the transit

circle. In the centre is the clock that provided the daily signals to drop the

time ball in the tower above and, through telegraph wires, the time ball in

Newcastle. On each side of the clock are chronographs for recording time. The

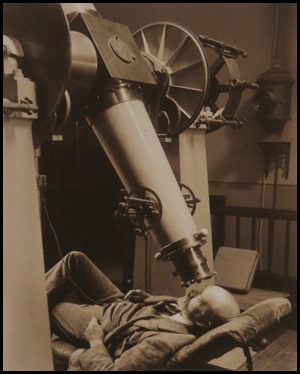

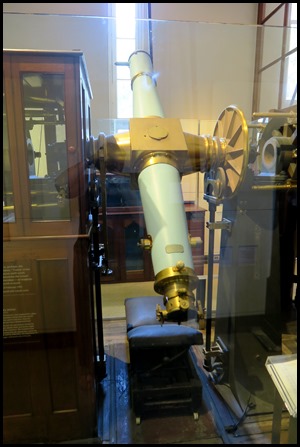

pivot tester is next to the clock.    The Transit Circle Telescope, Henry Alfred Lenehan observing.

As in any 19th-century observatory, the telescope was at the heart of the work

of Sydney Observatory. Known as the transit circle, it was used by astronomers

to find the exact time, the positions of the stars and the geographical

coordinates of the Observatory. To find time, the transit circle telescope

relied on the regular daily spin of the earth. As the Earth spun, stars passed

through the field of view of the eyepiece. Imagine a giant clock with only one

hand: the stars are then the numbers on the clock face and the telescope is the

hand showing the time. The grand astronomical clock dial on the ‘Strasburg’ clock model, made in 1889 (on

display in the Powerhouse Museum). H.C. Russell, The Australiasian, 28th of February

1903 said “I think this transit instrument is, perhaps, the most important

in the Observatory. Transit circles are telescopes that can only move

north-south. Astronomers used them to determine the instant the stars cross or

‘transit’ the meridian – an imaginary line passing overhead from north to

south”. The observing couch offered a reasonable degree of comfort as

the astronomers spent hours staring through the eyepiece. The couch was on

rollers so that the observer could manoeuvre themselves into appropriate

positions. Either end of the couch could be raised to provide

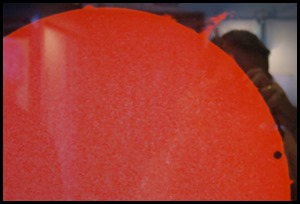

support   Geoff Wyatt’s image of the 2004 transit of

Venus was taken in the north dome here at the Sydney Observatory through

a special filter that only transmits the red light of hydrogen atoms. He used a

Coronado telescope and Nikon Coolpix camera to capture the spectacular image,

which was the first winner of the David Malin Award,

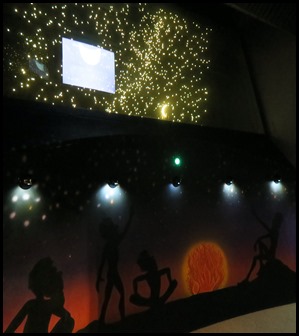

Australia’s premier prize for celestial photography.    We went into a small

area set aside for Aboriginal creation and dream

stories, we watched several child-like explanations for star

constellations – here are two. Whowie – The Bunyip: Many years ago

there lived on earth Whowie the bunyip. No person or animal was safe when Whowie

was about because he had the most insatiable appetite. The members of the tribe

gathered to kill Whowie by lighting a series of fires close to the monster’s

cave. When he was driven out by the smoke from the fires, the whole tribe

attacked him with their spears. He was so big and strong they took all day to

finally kill him. There has never been another bunyip to this day. But his shape

still fills the sky during December. And Whowie is the largest of the Sky

figures. Wathuarung – Victoria. Marigu Jarn – The Hunter: Jarn is a

youth who believed he was the best hunter of his tribe. He would hunt and show

off his catch to everyone. He also thought he was the best man in the tribe that

he deserved the best wife. Thus, he began to play his dancing sticks. As this

did not work, he then chased Marigu, the seven sisters, through the bush to try

catching a wife. In the evening sky in January, Jarn can be seen as the figure

playing his dancing sticks, while the seven women appear as a group of stars

huddled together to escape from him. Woorabinda-Biregada tribe –

Queensland.    Wolf Creek Crater. The Djaru say

‘There was once a wild man in the form of a star. He saw a woman sitting in

a spring of milky water, under which was tasty sugar leaf. In his hunger, he

came down from the sky and tried to kill the woman to get the sugar leaf. She

quickly moved and he plunged into the Earth, making the crater

the Djaru call Kandimalal’. Another story is ‘when the crescent moon

and the evening star passed very close to each other, the star became so hot

that it fell to the ground causing an enormous

explosion’. Small chunks of rock floating in space are called meteoroids.

As they fall through the Earth’s atmosphere, they heat up and generate visible

streaks of light (meteors). If they strike the Earth, they are known as

meteorites. Meteorites are generally classified as either stony or iron. The

most common type are stony meteorites. The Henbury and Wolfe Creek meteorites,

are mostly of nickel and iron. Wolfe Creek Meteorites. Weight 945,

245 and 210 grams. Wolfe Creek, in the far north of Western Australia, is one of

the best-preserved impact craters in the world. The 900 metre wide by 60 metre

deep crater was formed 300,000 years ago when a 50,000-ton meteorite struck the

Earth with great force. Identified by Europeans in 1947. Henbury Meteorite. Weight 575

grams. About 4,200 years ago a meteoroid broke apart in the atmosphere before

striking the Earth, 145 kilometres south of Alice Springs. The impact carved out

13 craters, the largest of which measures 180 metres wide by 15 metres deep.

Europeans identified the site in 1899 but did not realise it was formed by a

meteorite impact until 1931. Aboriginal people would not venture near the

craters, known as Tatyeye Kepmwere in the Arrente language, fearing the

fire-devil who came from the sun would fill them with iron.   ‘Shou lao’ figure, China – date

unknown. This figure of Shou lao or ‘the god of longevity’ was discovered in

Doctor’s Gully, Port Darwin in 1879. Carved in pinite, the figure holds a peach

and rides a deer. He is also named Shou xing which is the Chinese name for the

southern star Canopus. From the northern hemisphere

Shou xing/Canopus appears low in the sky and is rarely seen. The ancient Chinese

therefore believed that seeing Shou xing brings long life and good

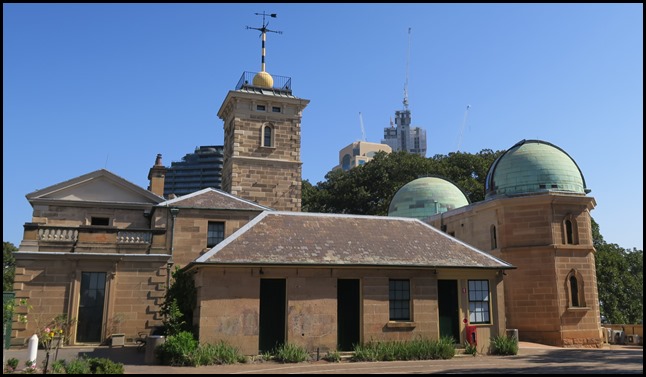

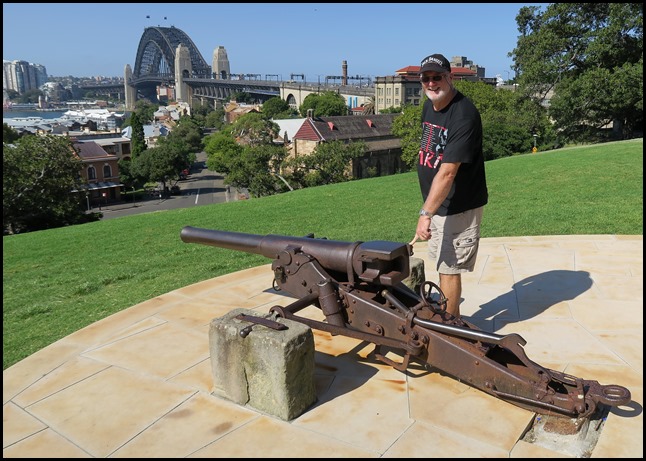

luck.  Outside we looked back to the rear of the

Observatory.  From here we had quite a view and of the War Memorial – this side dedicated to the Units of

Volunteers from New South Wales who responded to the Empire call – South African

War 1899-1902........and of course something for Bear’s

trigger finger..........  ALL IN ALL FASCINATING, LOTS

OF NEW STUFF

VERY WELL

PRESENTED |