The Other Side

|

The Other Side of the

River

We crossed the river in Baby

Beez and parked by the stump in the middle of

the picture. To the left all we could see from here were random stumps and

rocks. We were intrigued as Donald helped us up the steep bank.

At the end of the track we found

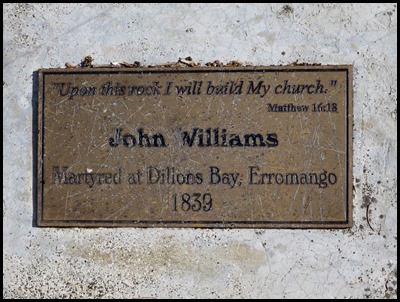

ourselves on a flat stone, to one side was the plaque to John Williams, the missionary. We had read

that his body was carried from the beach, placed on a stone and the the said

stone had been chipped in the way of measurement.

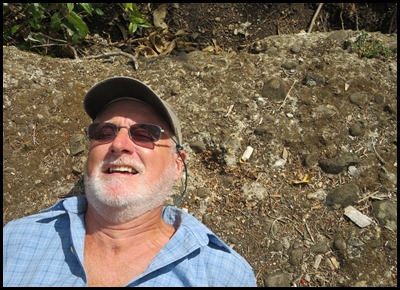

Donald and Bear stood and looked at

the ‘head mark’ – to the right of Donald’s foot. I

had expected to see a divot chipped out that looked like the white mark the

police used to draw in chalk around a dead body. I had to be happy with head and

foot marks.

Bear tried it

out for size, feet at the foot end and the head mark

just by his left ear – so John Williams was around six feet tall. We know

he had been a heavy set man. Donald filled in a bit more of the story, he

assured us it was not his village who had ordered the killing. the chief who did

lived on this side of the river. The body was ‘sold’ to another village up in

the hills.

We got back into Baby Beez and went down

the river to park by the beach on the same side of the river. Another track,

this time through grass, then low bushes and then we could see the odd, small

headstone. In a clearer area Donald pointed to the Memorial

to John Williams and James Harris, killed on the same day. Apparently

John’s remains were taken back to Canada, although James’ are here.

This article appeared on the Daily Mail

Online

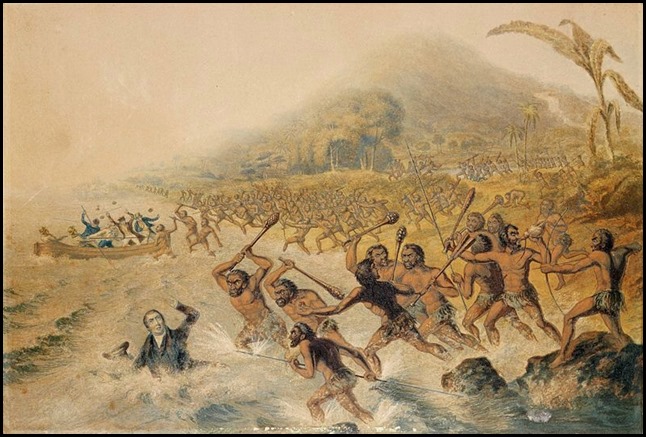

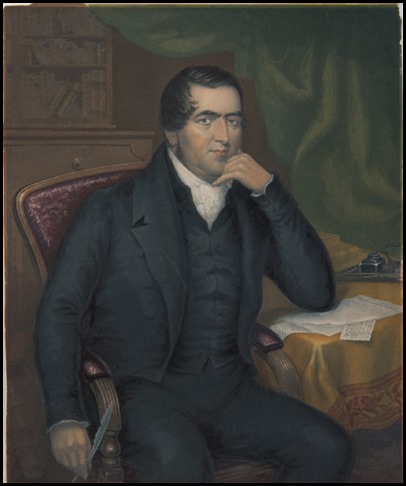

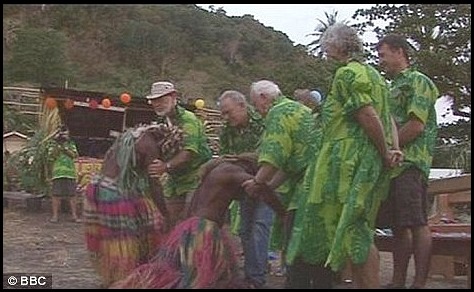

Sorry we ate your great-great grandpa: Island cannibals apologise for killing missionary 170 years ago. By Richard Shears for Mail Online. Updated: 21:16 GMT, on the 7th of December 2009 In a jungle clearing on a small Pacific island, the descendants of a tribe of cannibals bow to a British pensioner and apologise for having his relative for dinner - literally. The man they were apologising to was Charles Milner-Williams, 65, of Hampshire. The meal they were apologising for was his great-great grandfather, the Reverend John Williams, who was killed on the island of Erromango, now part of Vanuatu, 170 years ago. Williams, a prominent missionary of the 1830’s, travelled through the dangerous islands of the South Pacific trying to convert pagan tribes to Christianity. With fellow missionary James Harris, he stepped ashore from the ship Camden on to Erromango, part of what Captain James Cook had named as the New Hebrides. When the natives saw the two white men walking up the beach they set upon them with spears, clubs and arrows.

The captain of the missionary ship reported later that Harris, who was the furthest inland, was clubbed down and killed. Mr Milner-Williams said: 'John Williams turned and ran towards the sea. They caught up with him on the sea shore. 'They clubbed him and shot him with arrows and he died there in the shallows.'It was a Royal Navy ship that went back to the island. The islanders then said that yes, they had killed and eaten both Harris and Williams.' Seventeen decades later, it was a far more friendly group of islanders who greeted Mr Milner-Williams and 17 members of his family, who arrived on Erromango to receive the formal apology. In the sombre ceremony that followed, islanders bowed before the visitors and grasped their hands, clearing their consciences of past deeds. Mr Milner-Williams also agreed to accept responsibility for the education of a seven-year-old girl who was ceremonially handed to him in exchange for the loss of his great great grandfather. He said: 'I thought I would be dispassionate after 170 years, but the raw emotion, the genuine contrition, the heart-rending sorrow, has been hugely moving.' The tribe also said they believed the act lifted a curse that had dwelt among them, although they did not say what that was. The reconciliation event marked the 170th anniversary of the death of Williams and Harris. 'Erromango needs it very much,' said Mr Iolo Johnson Abbil, president of Vanuatu. He told the BBC, which showed the ceremony on Inside Out, BBC1, last night: 'People always look upon them that they killed a missionary. 'They think that it has a sort of curse on Erromango and that's why it's very important for them to have this reconciliation.' Anthropologist Ralph Regenvanu, who is also a member of the Vanuatu parliament, said: 'Saying sorry is part of it, but all reconciliation ceremonies require something from each side - there's always that element of exchange. 'Cannibalism, contrary to what a lot of people think, was traditionally a very ritualistic and sacred practice. 'It was not something like, you know, have your neighbour for lunch. 'It was practised in a very ritualistic way and was considered to be a very sacred activity.' Anthropologists believe Williams and Harris were eaten because they represented a threat as an enemy - an incursion of European civilisation that was coming into Erromango.

The presence of these missionaries in the colonies aroused public interest in missions and drew attention to trade with the Pacific islands. John Williams, who had a dynamic personality, believed that the Christianization of the islands in the Pacific would lead to the greater prosperity of Sydney's business houses. But he also believed Australia had a duty to evangelize and civilize, and wrote to the Sydney Gazette, published on the 22nd of March 1827: 'Prosper, O Australia! in your mercantile pursuits, in the extent of your dominions, in the numbers of your flocks and herds, in the fineness of your fleeces; yet recollect, that in your prosperity you are neglecting the work that God, the author of all your prosperity, has assigned you”'.

Another take. In 1839, John Williams and Jacob Harris landed on the beach at Dillon’s Bay, Erromango, in what was then known as the New Hebrides (now Vanuatu). Unfortunately for them, what Williams and Harris did not know was that just weeks before their arrival an Australian sandalwood trader had brutally murdered two boys, the sons of a local chief. As a result, the local people had resolved to violently repulse all contact with white people. If Williams had stayed on the beach, he would have been fine. But he was determined to proceed inland. His aim was to establish friendly relationships with the local islanders and to sow the seeds for the more difficult work of conversion by the London Missionary Society. So Williams, followed by Harris, pressed on, and in doing so unwittingly broke a powerful taboo.

The two men passed an important ritual marker made of lashed tree branches that signified the point beyond which foreigners could not pass. Williams either did not see or did not understand the sign, and as he stepped across, he was ambushed by local warriors, who chased them both back towards the beach, where they were bludgeoned to death and later ritually cannibalised.

Williams’ body was carried to a spot on to a limestone staircase, built by the river for loading and unloading trade goods. At the uphill part of the staircase is a semicircular structure built of lime mortar, with brick of a distinctive bright orange colour and coarse black temper inclusions. From here, the body was taken to a large limestone boulder. The body was laid out and small cupules were pecked to mark the location of Williams’ head, hands, and feet. Later, a small brass plaque was placed on the stone to commemorate the location. The body was then taken to another limestone boulder closer to the water, where it was divided among local chiefs to be cooked and ritually eaten. His skull was taken inland and later buried in an area now marked by a rotting coconut palm in a grove of larger mango and banyan trees.

Should the villagers have apologised. Many of these ‘contrition ceremonies’ have taken place across the Pacific. We felt that the past was the past and should stay there to be learned from. Donald believes it’s in the Bible to “say you are sorry”. Steve in the Secret Garden in Port Vila thinks that Erromango felt it was cursed and wanted to lift a dark cloud.

ALL IN ALL A SAD TALE ON BOTH SIDES SIGN OF THE TIMES – DON’T INTERFERE WITH OTHER CULTURES |