Exhibition

Beez Neez now Chy Whella

Big Bear and Pepe Millard

Sat 10 May 2014 22:57

|

The Underground

Exhibition

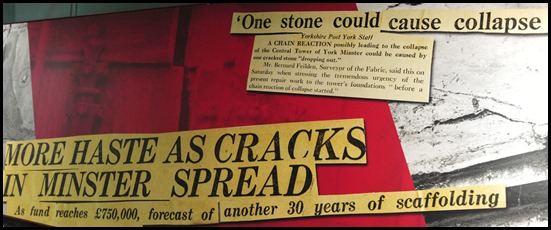

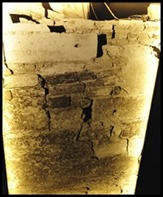

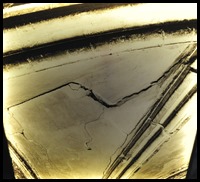

Uncertain Ground: Investigators found

major problems under the central tower. Over time its great weight has made it

sink into the ground. The present cathedral had also been built partly on top of

the foundation walls of earlier smaller structures. These walls were not strong

enough to support the much larger building.

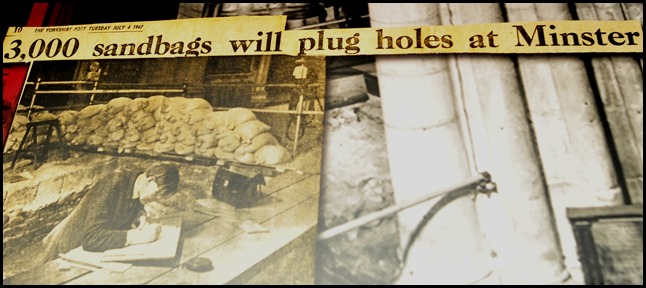

The Yorkshire Post: More than three

thousand sandbags are to be taken into York Minster to fill up holes to be made

by archaeologists. Mr. H.G. Ramm, from the Royal Commission on Historical

Monuments, said yesterday that the sandbags would be needed to fill in holes

deeper than six feet. The area under the central

tower, he said, was going to be taken out to a depth of six feet and the

archaeologists would be permitted to sink trenches into this area up to a

maximum depth of twelve feet.

Penelope Walton Rogers, archaeologist

and finds officer, remembering 1969: In the evenings things became quieter and

the Minster organist would often come in to practise. Digging late into the

night could be a genuinely Gothic experience, with Bach’s toccata ringing in

your ears.... We may have had to work long hours, but the entertainment was

good.

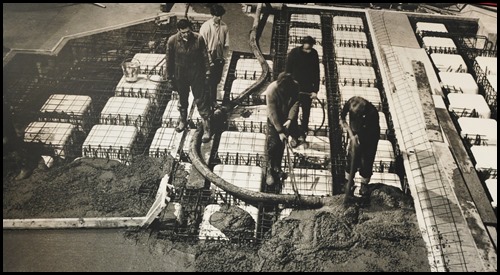

Bonds of

Steel: Nearly four hundred strengthening steel rods run through the

concrete, binding it to the old foundations.

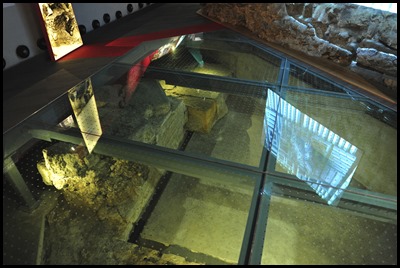

On Many

Levels: Under the glass lies the Norman level from the AD 300’s. Above

the concrete ledge ahead is the bottom of an outside wall of the Norman

Minster, built about 1080. The ground level around the Minster today is not much

higher than this. Above the inserted modern ceiling is the floor level of the

present Gothic Minster, dating from the 1200’s – it is higher than the ground

level outside.

People have lived, worked or

worshipped on this site for at least two thousand years. The first evidence of

Christianity found here is seventeen hundred years old. Archaeologists knew that

the Minster lay over the centre of York’s Roman fortress. What surprised them

was how much of the fortress was still buried under layers of later history.

Just above the Roman level they uncovered evidence of later Anglo-Saxon Minster.

Clues to the Lost Minster: The first

Minster at York was built and maintained by Anglo-Saxon kings and archbishops.

No trace of the building has been found, but objects shed some light on the

missing Anglo-Saxon Minster. In about 1030 a Viking nobleman called Ulf presented this horn as a symbol or record of his gift

of lands to the Minster. The horn is carved from an elephant’s tusk and is known

as an Oliphant. Tradition holds that Ulf filled it with wine, placed it on the

Minster’s altar, and so dedicated his land to God and the Minster. This transfer

was later confirmed by King Edward the Confessor. Ulf’s horn was made in

southern Italy, probably in the important trading port of Amalfi, where

craftsmen had easy access to ivory. The animal motifs copied from Syrian and

Babylonian art.

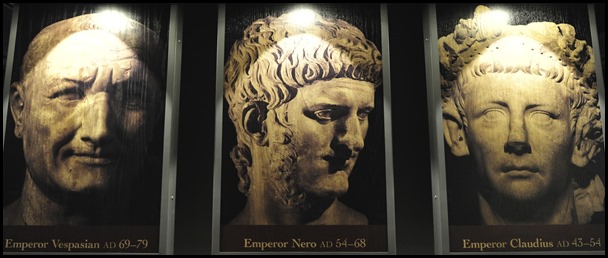

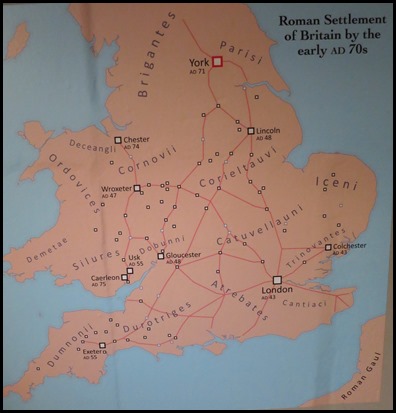

The present Minster sits above the

heart of the fortress at Eboracum – Roman York. From here, the army set

out to conquer northern Britain. This fortress was arguably the most important

military base in Roman Britain. Here, two emperors

died and one of the greatest was created.

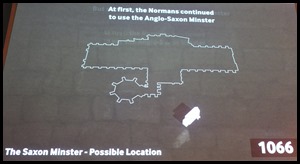

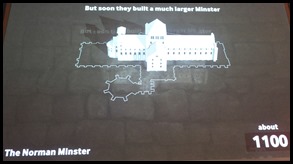

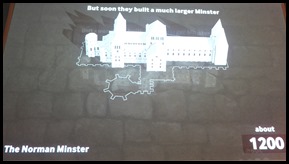

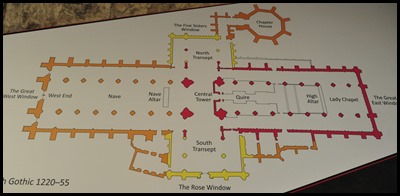

How the building has grown over the years. The Norman Minster was

one of the most impressive buildings in the land. It was gradually demolished

and replaced in stages by the present Gothic building. The work continued under

twenty Archbishops of York, many of whom helped to fund it. Improving the

Minster both glorified God and expressed their own power and status. The first

phase of rebuilding was begun around 1220 by Archbishop Walter de Gray. The

Minster was finally considered finished in 1472.

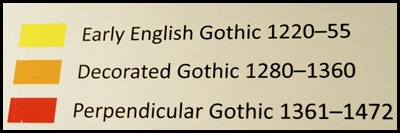

Artist’s

impression of the shrine of St William of York in the completed Gothic

Minster. It stood where the High Altar is now located.

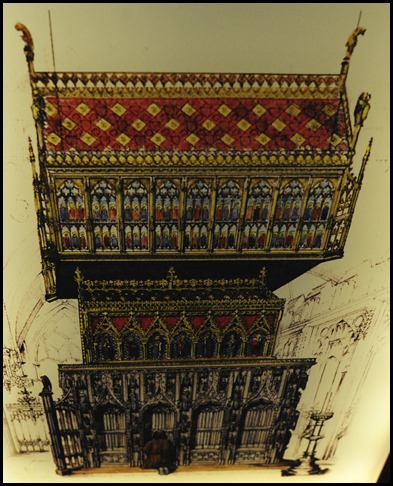

What happened to York just after the

end of Roman rule is unclear. Anglo-Saxons began settling in Britain, but the

city might have been largely abandoned. It reappears in historical records in AD

627 when the first Minster was built by Edwin, the Anglo-Saxon King of

Northumbria. The Minster remained at the heart of the city after Vikings seized

York in AD 867.

We rounded a corner and found

ourselves in an area full of displays.

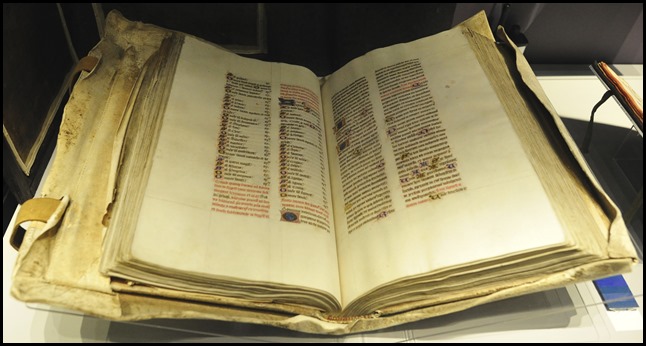

Missal of the Use

of York: A missal is a book used in the celebration of Mass or Holy

Communion. This missal dates from the mid-1400’s and contains wording and

instructions different from other versions of the Mass. This version is of the

Use of York, used in northern England before the reign of Henry

VIII.

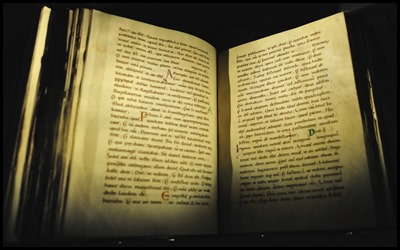

Gospel:

Comes from the Old English godspell meaning ‘good news’.

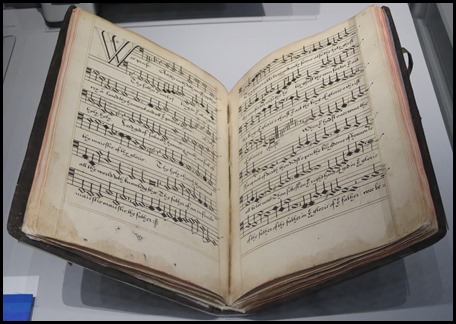

Part Book.

This is one of a set of five books in the Minster Archives written by the

Minster Choir and first used in about 1618. At that time each singer had a book

which showed his vocal only, and these were known as Part

Books.

Stone

Coffin: This is not Archbishop de Grey’s coffin, but is similar in form

and also dates from the 1200’s. Medieval stone coffins indicate that a person

was of high status. The hole in the bottom allowed fluids from the decomposing

body to drain into the ground underneath.

The remains of Archbishop Walter de

Grey, found in a similar stone coffin. Note the space above his head for his

bishop’s mitre or hat.

The Archbishop’s

Crosier: Bishops and archbishops carry crosiers shaped like shepherds’

crooks to symbolise their role as spiritual shepherds of people. This crosier is

still used by the Archbishop of York today and has a long and colourful

history.

In 1688 it was given by Queen

Catherine of Braganza – the Portuguese widow of Charles II – to the senior Roman

Catholic priest in northern England. As the priest was processing through York,

the Earl of Danby snatched the crosier from his hands. The Earl was clearly

offended by this display, at a time when Catholics were greatly distrusted in

England. By contrast, the crosier is today used as a symbol of unity between

Catholics and Protestants.

Archbishop Coggan’s Cope: Copes are

worn by all ranks of priest on some occasions, but are particularly associated

with bishops and archbishops.

This cope is of old-gold damask, and

was a gift from the Chapter of York to Donald Coggan, Archbishop of York from

1961 to 1974. The crossed keys are the symbol of St. Peter, to whom York Minster

is dedicated.

Oh dear. Oh dear. Oh dear

me. I need to sit down.

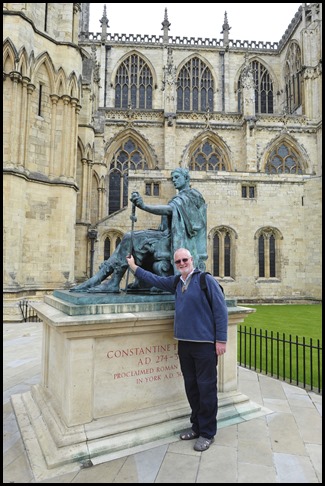

Thankfully, near the exit there was

an area with benches and three short films to watch. As we left we passed this

Roman column. We were near the spot where soldiers in

the Roman fortress proclaimed Constantine the Great their new emperor and

changed the course of history. Without this man, Christianity might have

remained a minor, persecuted religion. One thousand seven hundred years ago, we

would have been inside the basilica or ceremonial hall. This column is one of

the colonnades which ran down each side of the hall.

Outside, the man

himself is commemorated – which man – up to you dear

reader......

ALL IN ALL QUITE AN

INSIGHT |