J&PM Archive Gallery

|

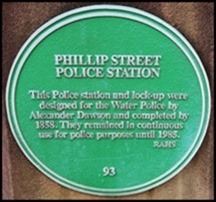

Justice and Police Museum Archive

Gallery     Today it was up, boiled eggs, up the steps, on

the bus and the rest of the day bimbling around the Justice

and Police Museum [only open at

weekends].  We had a really nice welcome from the ladies and there we were

in the first exhibition room – the former Court Clerk’s Office. The first

display we saw was of original boxes of evidence glass-plate

negatives. Handwritten at the bottom of the photograph of the little girl ‘Child. Unknown. Found wandering at large’.

Speed Graphic

camera, ‘pre-anniversary model’, Graflex, 1930’s. The robust and

lightweight ‘Speed Graphic’ was the camera of choice for newspaper and police

photographers. The other end of the room used to be divided and was the

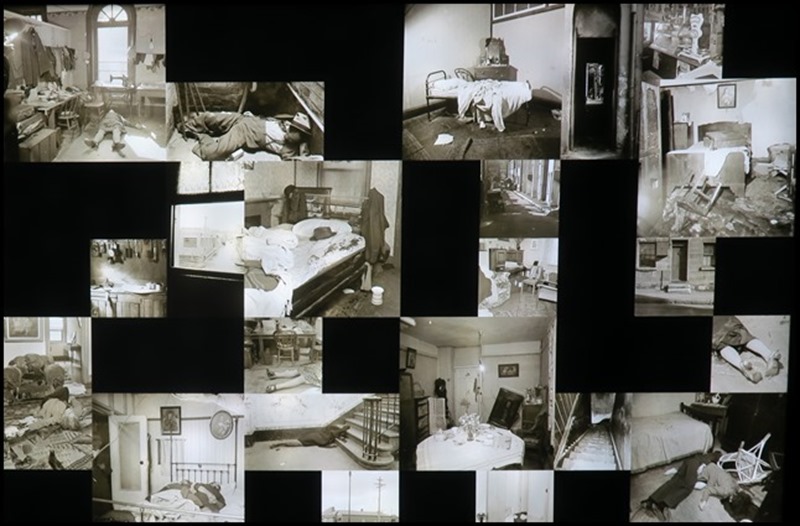

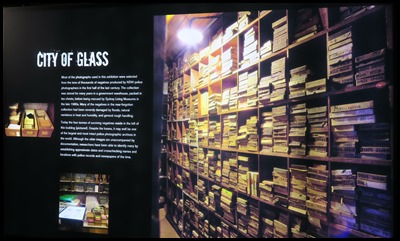

Magistrate’s Office then Parking Court.   City of Glass: Most of the

photographs used in this exhibition were selected from tens of thousands of

negatives produced by NSW police photographers in the first half of the last

century. The collection was stored for many years in a government warehouse,

packed in tea chests, before being rescued by Sydney Living Museums in the late

1980’s. Many of the negatives in the near-forgotten collection had been severely

damaged by heat and humidity, and general rough handling. Today four tonnes of surviving negatives reside in this

building [pictures]. Despite the losses, it may well be one of the largest and

most intact police photographic archives in the world. Although the older images

are unaccompanied by documentation, researchers have been able to identify many

by establishing locations with police records and newspapers of the

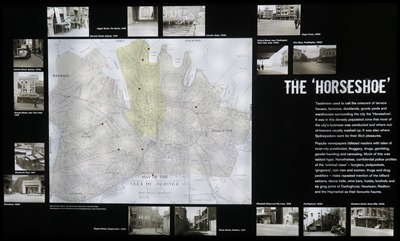

time. The Horseshoe: Taxi drivers used to

call the crescent of terraced houses, factories, docklands, goods yards and

warehouses surrounding the city the ‘Horseshoe’. It was in this densely

populated zone that most of the city’s business was conducted and where

out-of-towners usually washed up. It was also where Sydneysiders went for their

illicit pleasures. Popular newspapers titillated readers with tales of inner-city

prostitution, thuggery, drugs, gambling, gender-bending and carousing. Much of

this was tabloid hype. Nonetheless, confidential police profiles of the

‘criminal class’ – burglars, pickpockets, ‘gingerers’, con men and women, thugs

and drug peddlers – make repeated mention of the billiard saloons, dance halls,

wine bars, hotels, brothels and sly grog joints of Darlinghurst, Newtown,

Redfern and the Haymarket as their favourite haunts. These historical images expose the secret places, domestic spaces and streetscapes of Sydney, as well as the city’s criminal characters and their victims. They document the daily activities of the police photographers who calmly recorded the scenes of mayhem with a rational gaze and a steady hand. We are thrilled to have been given permission to photograph the photographs and blog about them. Warning, images of murder will follow.

The Beat: Most of the early police photographs were taken within a few miles of the Criminal Investigation Branch in Central Street in the city. In many cases there is little idea why the photograph was taken. A great number of scenes, however, are recognisable as the streets of Surry Hills, Darlinghurst, Redfern, Paddington, Broadway, Chippendale, Glebe and waterfront area. Police photographers then were as much occupied with attending motor accidents, industrial accidents and fires as they were in dealing with crime, and many of the photographs show groups of locals gathered around car and truck smashes. Other photographs of deserted back alleys, yards, dead-end streets, vacant lots and urban badlands, have a more sinister cast. The photographs also offer a huge amount of unintended background detail: building facades, shop windows, street signs, billboards, advertisements and everyday people going about their business. The unsentimental view of urban life revealed was at odds with the picturesque photographic conventions of that time. However, some of the moody streetscapes and empty spaces are reminiscent of the work of between-the-wars artists such as Edward Hopper. Years later, a similarly downbeat visual style was to emerge in cinema, as filmmakers consciously emulated the hard-boiled ‘police procedural’ view of the city in creating post war film noir.

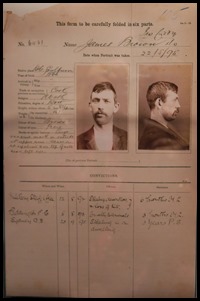

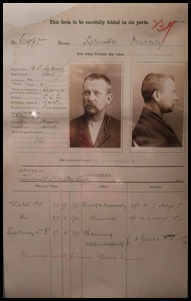

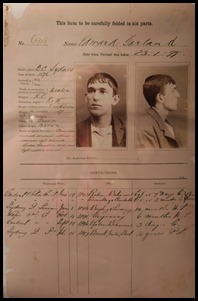

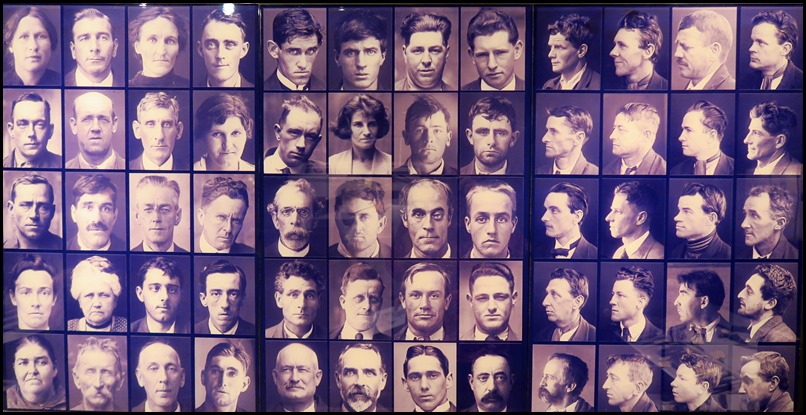

Rogues Gallery: During the years 1912-1930 Sydney police photographed two and a half thousand actual suspected criminals, or ‘persons of interest’. Over a thousand of those portraits have been uncovered during research into the police archive. Most were taken in the cells at Central Police Station. Other mug shot locations have been identified as Paddington, Redfern, Darlinghurst, North Sydney and Newtown police stations. Police records refer to these lively, often surprisingly informal portraits as ‘Special Photographs’. It is not known what criteria were used in deciding who was photographed. A number of the subjects are not found in police records at all – in some cases it appears they were simply unlucky enough to be found in the company of a suspect. Others were charged with relatively minor offences.Generally, however, people charged with such everyday offences as simple assault, drunkenness, prostitution, offensive behaviour, consorting, drug possession, illegal gambling and ‘sly-grogging’ are under-represented in the photo archive. The majority of subjects identified so far are ‘working’ criminals – confidence men and women, forgers, false pretenders, pickpockets, housebreakers, sneak thieves, ‘hotel barbers’, bag snatchers, safecrackers, drug sellers and thieves. Contrary to researchers’ expectations, few of the better remembered names of Sydney’s 1920’s criminal world have been found among the ‘Special Photographs’.

Sydney’s Dark Places: In the days when these photographs were taken, the details of home life were not generally discussed in public, rarely written about, and depicted – if at all – only in the most idealised ways. The front door of the domestic dwelling presented an almost total barrier between the public life of the street and the private life of the home. Fatal accidents or violent crime shattered that secrecy. The private workings of the crime scene suddenly became a public matter. As forensics assumed an increasing importance in police work, detectives learned how to observe and note minute details of crime and accident scenes. Police photographers in particular strove to make accurate, inclusive records of interior scenes exactly the way they found them. Without intending to, they thus established a large yet intimate ‘ethnographic’ record of private life in Sydney at the time. Many of the photographs show cramped, grimy interiors of boarding houses and flats. Greasy surfaces, unswept floors, bare walls, and empty bottles on tables and bedroom dressers all suggest transient, borderline lives. Other photographs however, reveal well-kept interiors, crowded with neatly ordered furniture, bric-a-brac and framed pictures.

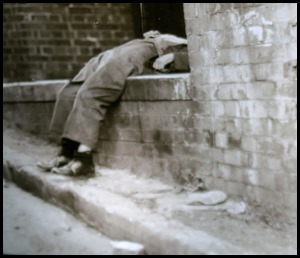

Some of suspected crimes committed in the street.

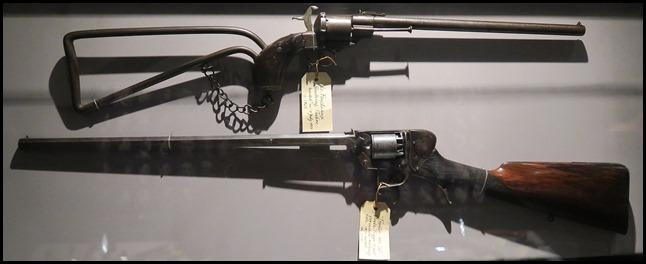

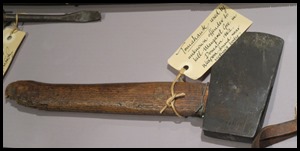

Crime Room: Formerly the Inspector’s Office, this room featured confiscated weapons – a surprising number taken by the railway police, including the mace. It is based on a police collection used to train new police recruits .........................

......................................arrest sheets............................

.............................and a rogues gallery.  The Archive Gallery: This room is an exhibition space for

selected images from the Museum’s forensic photography archive. The archive was

originally created by the NSW Police between 1912 and 1964 and contains an

estimated 130,000 negatives, The collection includes images of suspects accidents, murders, fires, forgeries and

fingerprints. In 1990 the Historic Houses Trust rescued the archive from a

flooded warehouse. Since 2006 the Justice and Police Museum has embarked on an

extensive project to preserve, digitise and catalogue the photographs. Much of

the collection resides in small brown envelopes inscribed with brief, enigmatic

police notes: date, photographer’s name and location of the crime scene.

Sometimes there is a terse description of the circumstances, sometimes much

less.

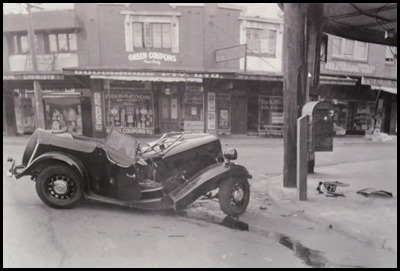

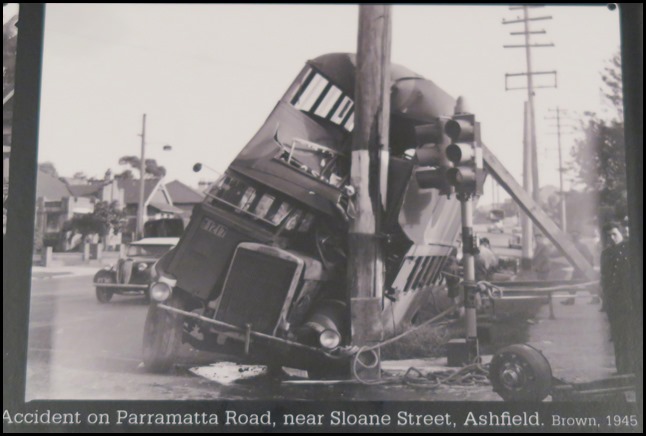

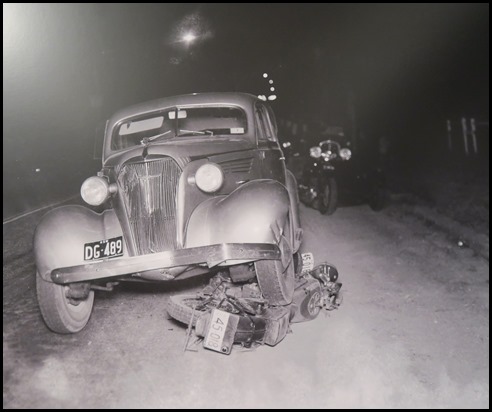

Documenting the Scene: Police

photographers documented traffic accidents and mishaps across New South Wales.

They could be called to accidents in the city, suburbs or country areas at any

time, day or night. During the 1930’s, when police were still establishing their

photographic practices, only one or two views of each crashed vehicle were

taken. In later years, developments in technology allowed for more systematic

recording. From the mid-1940’s, police photographers began documenting the

general location of an accident, the damaged vehicles in situ, different

viewpoints and close-ups. These photographs helped investigators to determine

whether any law had been violated, and, if required, the images were presented

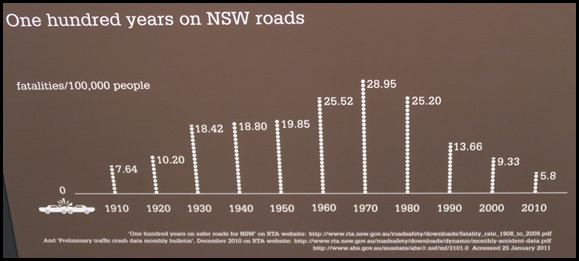

as evidence in court.  Fatalities/100,000 people 1910 to

2010. New South Wales police have enforced traffic law since the

first Police Traffic Branch was established in 1900. From the late 1930’s,

police photographers supported this growing area of investigation by routinely

recording smashed vehicles and traffic accidents. The prosperity and expansion

of 1950’s Sydney led to a dramatic rise in the number of motor cars on the

roads, and the quantity of photographs taken by police increased accordingly.

The number of registered vehicles in New South Wales grew from 276,184 in 1945

to 613,554 in 1955, then almost doubled to 1,198,567 by 1965, when trips taken

by private motor car outnumbered for the first time those made by public

transport.  These photographs reveal the confronting and chaotic accident

scenes faced by police investigators. They also show how, over time, the motor

car changed Sydney’s streetscapes as road markings,

traffic lights and direction signage were introduced. In addition, they document

the steady progression of automotive design as car manufacturers released newer

and safer models.  Officers in uniform

demonstrating the operation of a radar set at

Sydney University. Walter Tuchin, 1954. Policing the Traffic: The Motor

Traffic Act 1909 gave police greater control over motor vehicle registration,

licensing, road safety and driver testing. However, improvements such as traffic

lights, bus lanes, directional signs and road markings were not instituted until

the late 1930’s. The increase in the number of motor cars on the roads also led

authorities to introduce driver education and road safety reforms. In 1937 one

newspaper identified speed as the single greatest cause of traffic accidents. At

that time, the speed limit in built-up areas was thirty miles an hour, but there

was no way to detect exact speeds. ‘Scorchers’ or speeding drivers, were often

prosecuted for ‘furious driving’ instead. It wasn’t until November 1954 that

radar sets, developed by CSIRO [Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research

Organisation scientists, were first used in new South Wales. As we left the

museum, there was a glorious aroma of curry coming from an Indian restaurant a

few strides down the hill – had to be and delicious it was. We end with an

Ooops.  ALL IN ALL WONDERFUL OLD

SCENES

AN AMAZINGLY FRANK DISPLAY OF

EVIDENCE |