Governor's House

Beez Neez now Chy Whella

Big Bear and Pepe Millard

Sat 9 Jan 2016 23:27

|

Governor's House

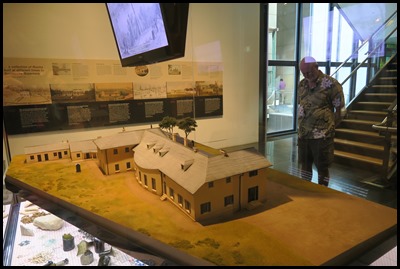

On our visit to the Museum of Sydney,

we took the first set of stairs and dominating the space was this marvellous model. The first Government House [1788-1845]

used to stand on this site, it was a six-room dwelling built in just over a year

for the colony’s first governor. Governor Phillip’s house was built using

convict labour, with sandstone foundations, locally made clay bricks, imported

glass, and shell and pipeclay mortar. It was just one room deep. As alterations

and additions were made by successive governors, it grew into a rambling house

by the time it was demolished nearly sixty years later.

Developing this model

was a challenging exercise for the museum. While the appearance of the front of

the house is well known, the back is more of a mystery. Through careful

detective work, with pictures, archaeological evidence, documentary research,

examination of surviving contemporary buildings and collaboration with

architectural historians, plans were prepared for the

model maker. The key pieces of evidence used were the 1836 watercolour by

Charles Rodius, the 1829 view by Thomas Woore, which is the only known detailed

nineteenth century image of the rear of the house, and the floor plan prepared

in 1845 for the report that recommended the house’s demolition.

The evolution

of the house to its final documented form can be traced within this model. Of

the other buildings on the site, only the kitchen and main outbuildings are

shown, for reasons of scale.

Artifacts from the Site: The first archaeological dig on

this site, in February 1983, revealed the foundations of Governor Phillip’s

house. This and later digs uncovered a wealth of artefacts. Many can be dated to

the first Government House, and tell so much about its construction and life.

Fragments of window glass, nails, sandstone, bricks and locally made clay tiles

– soon replaced with shingles – add to the knowledge gained from excavated

drains, footings and walls, including those of Governor Macquaries’ bow-fronted

Great Saloon’. Shards of ceramic, from fine china to utilitarian earthenware,

fragments of stemmed glassware and clay pipes, oyster shells, bottles, bones

bearing butchering marks, and lumps of charcoal and coal all provide insights

into those who lived in, worked in and visited the first Government House.

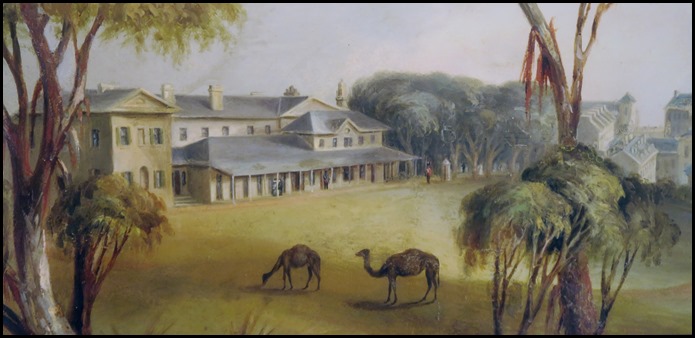

1791. This

watercolour by Joseph Bradley shows the first Government House about three years

after the foundation stone was laid on the 15th of May 1788. The two-storey

brick residence, with cellars below, was completed by June 1789. Its six rooms

were supplemented by skillion-roofed additions and a stairhall to the rear, and

several outbuildings. The garden and outbuildings were enclosed with a palisade

fence, and a walled forecourt had sentry boxes at each end, which were soon

replaced to either side of the house. This building replaced the portable canvas

house, erected on the eastern side of what became known as the Tank Stream, in

which Governor Phillip had lived when he arrived in the colony.

Taking of Colbee

and Benalon. William Bradley watercolour, from his journal ‘A voyage to

New South Wales’, 1786-1792. Aboriginal people generally avoided the early

settlement. Governor Phillip even resorted to kidnap to establish regular

contact. After a dramatic reconciliation, Aboriginal people began to frequent

the settlement and became a constant presence in and around Government House.

Some sought food, assistance or refuge; others dined with the governor or lived

periodically in the house complex. The yard was said to be always open to the

often large groups of Aboriginal people who passed through the settlement.

Friendships were formed with individual men and women, and several Aboriginal

people were buried in the governors’ garden.

Historic Events: Government House was

the site of significant events in the colony’s history. A printery began

operating in an outbuilding in 1795. Here the first Australian book was printed

in 1802 and the first issue of the Sydney Gazette in March 1803. A new

printing office was constructed adjacent to the house in 1805. The most

momentous event occurred in January 180 when Governor William Bligh [he of the

popular kind with both officers and men at sea] was overthrown and placed under

house arrest in what became known as the ‘Rum Rebellion’. More fittingly,

Government House also hosted the first meeting of the Legislative Council in

1824.

The Governor’s Garden: Initially the

governor’s garden was laid out for food production, with plants from England,

Rio de Janeiro and the Cape of Good Hope. Several Norfolk Island pines were also

planted, interspersed with native vegetation. Gradually the garden became more

ornamental, with exotic species, a grand carriage loop, a shrubbery and a

grassed slope down to a foreshore wall. The last of an avenue of stone pines

along the entrance drive survived until 1901. Major changes to the garden and

grounds by Bligh and the Macquaries created a picturesque

landscape.

Philip Gidley

King and is wife Anna Josepha, and their children Elizabeth, Anna Maria

and Phillip Parker. A watercolour by Robert Dighton, 1799. Government House,

vice-general residence, office and venue, became a family home with the arrival

of Governor King and his family in 1800. The presence of children called for

nurses and schoolrooms. Some servants arrived with the governors; others were

engaged in the colony. Furniture and furnishings were imported or acquired

locally, but governors also brought their own possessions with them and often

sold them on departure. In 1805 Mary King was the first governor’s child born in

the house, and in 1814 the birth of Lachlan Macquarie junior was joyfully

welcomed. Mrs Darling bore a daughter and two sons in the house, one of whom

died there before his second birthday.

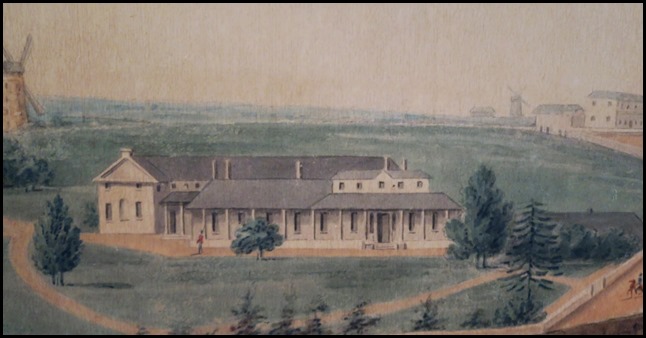

1809. This

George William Evans watercolour shows the significant changes the house had

undergone by 1809. When Governor King assumed command in 1800 he found the house

uninhabitable until it had been reroofed. King built a long drawing room to the

east, and in 1802 extended the existing verandah, probably added by Acting

Governor Major Francis Grose in about 1794. A bedroom and dressing room appear

to have been built behind the drawing room. Governor William Bligh arrived in

1806 and made further extensive repairs. He had the shrubbery laid out in walks

and all the rocks in the garden were blown up and removed. The house was painted

and repaired again for the arrival of Governor Macquarie at the end of

1809.

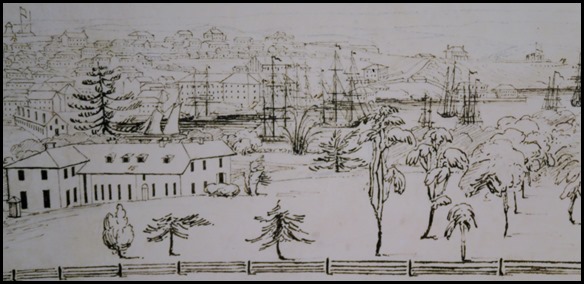

By 1820

when this watercolour was painted Governor Macquarie had extended the house in

two stages. Between 1810 and 1812 three rooms were constructed at the rear: a

large bow-fronted dining room or ‘Great Saloon’, a family bedroom and an office.

The rear skillion rooms and stairhall were demolished and replaced. From 1818 to

1819 Macquarie’s mew east wing was extended and given a second story. This

gabled wing, attributed to architect Francis Greenway, was separated from the

long drawing room by a recessed porch, later glazed in. However, Governor

Brisbane, who succeeded Macquarie, found the house unsuitable and resided mostly

at Parramatta. Few changes were made to Government House during his term,

although the verandah was significantly altered or extended in

1824.

Thomas Woore’s 1829 drawing shows the house from the rear after the last

known extensions had been completed. The house had been repaired in 1825 for

Governor Darling’s arrival and new rooms added within the roof. In 1827 a new

servants’ hall was added to the rear, with bedrooms above. Two extra bedrooms

were created upstairs by raising the walls and completing the west wing. A

staircase and gallery were built along the front by altering the roof, linking

the two ends of the house. In 1828 the kitchen and other out offices were

rebuilt, the verandah reflagged and a cross wall constructed from the front gate

to screen the back of the house from the main approach.

Government House [and part of the

town of Sydney] – a hand-coloured lithograph by Augustus

Earle, 1830. A Social Hub: Royal birthdays and other special occasions

were celebrated at Government House with levees and dinners for officers,

gentlemen and foreign visitors. Those events were enlivened by regimental bands;

later there were balls, suppers and fireworks. The governor entertained

regularly, holding intimate dinners, musical evenings, family celebrations, tea

parties, dances and card evenings. Hundreds eventually attended balls at the

residence, so temporary structures were erected as supper rooms. Decorations

were increasingly elaborate – festooned leaves and flowers, flags, Chinese

lamps, bayonets, transparent paintings, chalked floors and intricate

illuminations. An invitation to Government House became a benchmark of

respectability.

1836. This

watercolour by Charles Rodius is generally regarded as the most accurate

portrayal of the house. By 1831 the residence included a drawing room, dining

room, butler’s pantry, servants’ hall, schoolroom, governor’s office, halls,

anteroom, eleven bedrooms and a bathroom, with separate laundry, kitchen and

quarters. It was repaired and painted for Governor Bourke’s arrival at the end

of the year. By then the drawing room windows had either been extended down to

the floor or converted to French windows. Repairs continued – leaky shingling

caused a ceiling to fall down, new privies were built south of the main

outbuildings in 1837, and the kitchen buildings were substantially repaired or

rebuilt after a fire in 1840.

1845.

‘Old’ Government House – ‘an incongruous mass of buildings built at different

periods’ – was vacated in 1845. Governor Gipps moved his household to the new

Government House just completed above Bennelong Point and still in use today. In

August 1845 a Board of Survey judged the old building to be unsound and

dangerous, too costly to repair and in the way of proposed new streets and

allotments. Demolition was recommended and promptly approved. By January 1846

much of the house was gone; by March Philip’s original building and those parts

in the way of the extension in Bridge Street had been cleared away. The east

wing was demolished by May, in August the old bricks were sold and by December

1846 the first Government House had almost disappeared.

The house and its grounds prevented

the expansion of the town to the east. In 1825 Governor Brisbane suggested

selling the water frontage along the east side of Sydney Cove to fund

construction of a new residence. This was echoed in 1832 by the Surveyor

General, who also proposed that the old house be removed so that the streets

could be realigned. The building’s demolition was also periodically urged by the

press. The plan [unknown artist], which accompanied

the 15th of September 1845 Board of Survey report that recommended demolition,

reveals the old house’s fate – it and its drive, paths and gardens are shown

overlaid with streets and allotments.

Comments

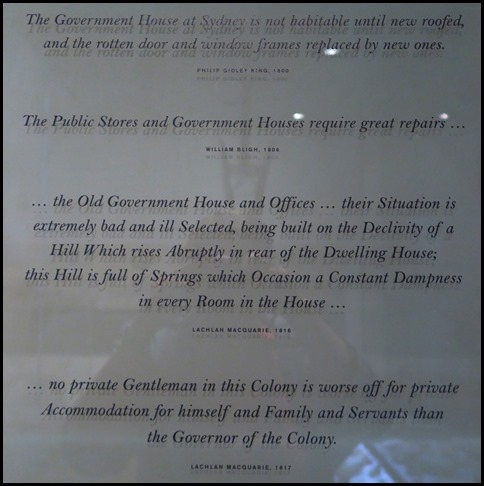

from Governors on the house.

Upstairs in the Museum we could see a

‘footprint’ of the first Government House Place,

which has now been preserved as a public space. This site marks a crucial

turning point in Australian history: a symbol of 1788 and British colonisation,

some say invasion, it means different things to different people.

In the 1980’s, on the verge of the

development of a multi-story building on this site, archaeologists exposed the

remains of the First Government House. After a sustained public campaign to save

the site, Premier Neville Wran announced on the 12th of October 1984 that the

foundations would be preserved.

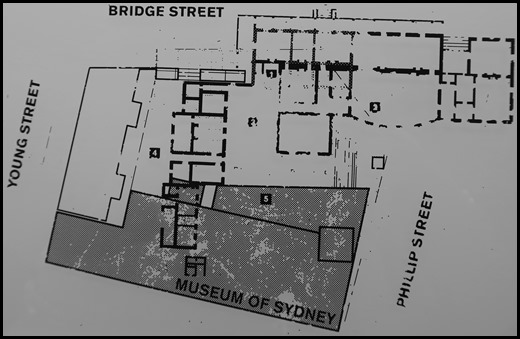

The Plan.

Steel studs mark the outline of Governor Philip’s original house [1] and white

granite traces the final form of the house with additions made by the successive

eight governors to 1845 [2]. The grid of archaeological excavation of the site,

1982-1992, is marked in black granite.

The sculpture Edge of the Trees by

Janet Laurence and Fiona Foley, [4] symbolises the first encounter between the

Cadigal people and the strangers of the First Fleet as they came ashore in 1788.

The Museum of Sydney on the site of the first Government House [5] opened in

1995, designed by architects Denton Corker Marshall.

The harbour always dominated the view

from the first Government House and can still be glimpsed today, although the

view was obscured in 1962 by Sydney’s first skyscraper, the AMP

building.

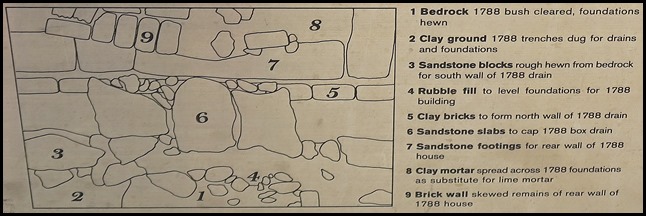

Looking down into the Museum foyer,

there are glass panels looking down to a drain, the

skeleton of a dog and some foundations.

“........having a good

foundation......I presume it will stand for a great many years.” Arthur

Philip 1788.

Outside. Alas, the house has gone.

But Philip’s foundations have withstood many changes in this place. Excavated in

1983 from their asphalt grave, they are now exposed to public view in this environmentally-controlled showcase. Here are Australia’s

first bricks, transported on the First Fleet or made in the Brickfields from

Sydney clay. Here too the first blocks hewn from age-old Sydney sandstone. The

sprawling footings and drains that later governors added to Philip’s foundations

have been preserved for posterity. Finally, a picture of the

‘new’ house [we would tour before leaving Sydney] a few minutes walk

away. Crossing Macquarie Street, to the Conservatorium of Music [initially built

for Elizabeth Macquarie because she missed the castles of home – her husband and

Francis Greenway came up with the idea of making a ‘castle’ like structure to be

used as stables.........no surprise that there was public outcry]. From the Con,

turn left and there is this fine looking building.

ALL IN ALL A FASCINATING

HISTORY OF A HOUSE

A VERY IMPRESSIVE

STORY |