Collingwood Beginnings

|

Collingwood Beginnings

Collingwood and Pakawai. J. Stowe, 1864

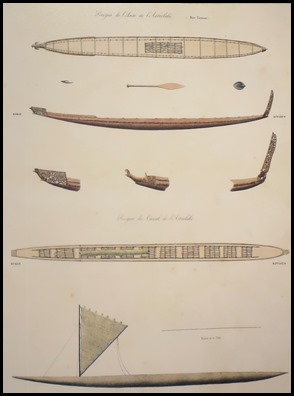

Te Tau Ihu o Te Waka – The Prow of the Canoe. Māori cosmology, combining whakapapa/genealogy with creation, explains how the gods formed Aotearoa / New Zealand. Polynesian sealore features Kupe and Maui gifted with superhuman powers who sculpted lands raised from the ocean. Te Tau Ihu o Te Waka extends from the north west at Kahurangi Point to Kairaripe / Cloudy Bay on the east coast. Māori tell of sailors from the Pacific, long before European exploration and circumnavigation of the globe. Traditions of the great migration from Hawaiki describe dozens of waka / canoes which journeyed here in the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries. While some returned, others remained but always kept Hawaiki in their souls. Journey of the Māori R M Hiroma:- Our tribal stories tell us that at the death of our bodies our spirits live on and journey back to Hawaiki; to the meeting place of the spirits at Great Hawaiki, Long Hawaiki,Hawaiki Far Away. Life then is a journey from Hawaiki to Hawaiki, the spiritual homeland of the Māori. And Hawaiki is with us always, carried in our hearts through thousands of generations and thousands of years of migration; carried also through the lifetime of a single heart wherever it may journey.

Māori artifacts and Tasman Bay Canoes,

1833.

Te Reinga, Cape Farewell, is the place from which the spirits of South Island Māori depart for Hawaiki among the stars. The Kurahaupo waka made landfall at Tauranga / Bay of Plenty on the North Island and Ngati Kuia travelled on to the South Island to step ashore at Te Tai Tapu, West Whanganui / Westhaven Inlet. Ngati Kuia would continue eastwards to settle in the Pelorus and Marlborough Sounds. Many iwi shifted location with territory relinquished, slaves held, marriages arranged. By the fifteenth century Ngati Tumatakokiri – Taupo, Wanganui, North Island, settled in Te Tau Ihu and pushed Ngati Wairangi south into Westland. Ngati Tumatakokiri occupied Te Tau Ihu from Wairau / Marlborough to Mohua / Golden Bay and survived two centuries without challenge.

1642 Abel Janszoon Tasman, The Dutch East India Company, Heemskerck, Zeehaen. Tasman embarked from

Jakarta. He sighted the Southern Alps on the 13th of December and sailed north

along the west coast. He dropped anchor at Clijppijgen Hoeck – Rocky Point and

recorded Onetahua as Duijnich Randt – Duney Land. Sailing east they sighted

smoke, fires and canoes along the coast. Tasman anchored off Wharawharangi.

Ngati Tumatakokiri sent out waka – canoes. Each side exchanged calls. The next

morning this encounter ended in tragedy when Heemskerck sent a crew to alert

Zeehaaen to discourage Māori from boarding the ships, the Dutchmen were attacked

and four were killed. Tasman departed and entered Moordenaers Bay – Murderers

Bay in the log.

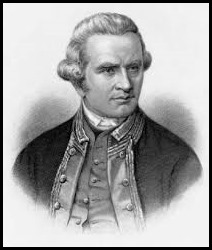

1170, 1773, 1777 Captain James Cook, Endeavour, Resolution, Adventure, Discovery. Landfall at Poverty Bay on the 6th of October 1769. First circumnavigation of New Zealand. In 1770 Cook anchored in Queen Charlotte Sound and named his favourite shelter Ship Cove. Long stopovers enabled crew to conduct and restock the ship, and scientists to record observations. On the first trip Cook sailed around the North Island, entered Massacre Bay / Murderers Bay from Taranaki then anchored at Ship Cove before sailing around the South Island. His last sighting of New Zealand was To Tai Tapu where he named the cliffs Cape Farewell. In 1773-74 and 1777, Cook journeyed with a second vessel to extend the British exploration. Each time he crossed between the North and the South Islands through the stretch of water now known as Cook Strait. Although the British established a penal colony at Botany Bay, Australia, in 1778, it would be more than fifty years before the colonisation of New Zealand and the Treaty of Waitangi.

1827 Dumont D’Urville. French Navy, Astrolabe. Sailed from Port Jackson, Australia. Landfall the 10th of January, 1827, South Westland. D’Urville navigated from Cook’s charts. He passed Cape Foulwind and Onetahau / Farewell Spit to anchor in Tasman Bay. On departing the Astrolabe struck the reefs in French Pass but reached the calm waters of Admiralty Bay. D’Urville’s detailed log updated international maritime maps and informed the colonial expedition of the New Zealand Company in 1839.

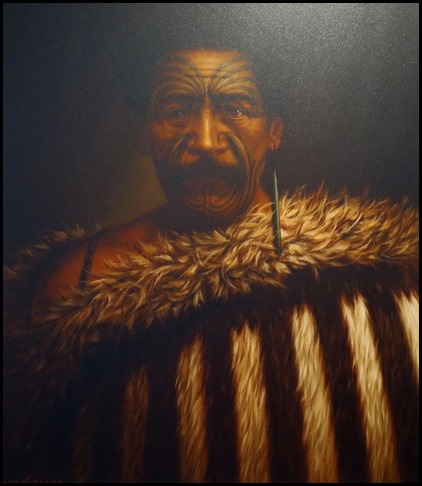

Tamati Pirimona

Marino.

The Treaty of Waitangi

was signed on the 6th of February 1840 and then travelled the nation to gather

signatures. In Te Tau Ihu twenty seven chiefs signed at Queen Charlotte Sound,

nine signed at Kairaripe – Cloudy Bay and thirteen signed at Rangitoto –

D’Urville Island. Queen’s sovereignty over South Island was then declared at

Port Underwood. The chiefs of Te Tai o Whakatu and Mohua hapu were given no

opportunity to sign though they probably would have concurred with their whanau

– families in the east. The New Zealand Company continued to push the boundaries

of claimed land and this culminated in the fatal incident in 1843.

The Mohua, the Company initially claimed

land purchases that extended to the Aorere River, but not beyond. This changed

with the discovery of coal and gold. Their first exploration of ‘Massacre Bay’

was in early 1842. They sailed around Te Matau – Separation Point to land at

Taupo, then Tata. They investigated the coast, noted pa on each side of the

estuary at Parapara and Tukurua, and went ashore at Aorere.

A Dommett, The Nelson Examiner, 19th of

November 1842:- The Hauriri chief, Erino was decently dressed in European

clothes. In manner, he is very mild and quiet with a touch of reserve and

sufficient self-respect – in fact, more of a ‘gentleman’ than any chief we have

seen.

Tamati Pirimona was chief at Aorere. The

Māori settlement at the estuary of the Aorere River often provided food and

lodging to the New Zealand Company, surveyors and other visitors.

S Stephens, Journal, 12th of March 1844:-

At Aorere Pa, Erino.......received us in the most hospitable manner and

having learnt from the boatmen that I was coming got one of his houses ready for

our reception, with a blazing fire in it and a pot of potatoes and some fish

already cooked.

Marino held interests in gold and operated

trading vessels out of Nelson. Erena assisted with the salvage of goods

from the Louisa Campbell at Onetahau, in 1847. He owned Occupation

Reserves in Collingwood district and Westport. In 1860, Marino accompanied

Mackay on the Arahura land purchase expedition to Te Tai Poutini. At the

outbreak of the Taranaki wars some alliance chiefs returned to the North Island,

but Marino remained in Mohua and aligned with other chiefs professing loyalty to

the Crown. Marino died in 1876 and his body was brought back to Aorere by sea.

He is buried in the historic cemetery in Collingwood.

On the grass plain below Lake Arthur/Rotoiti, W Fox, 1846.

Surveyors.

For the New Zealand Company surveying the new colony was

a priority. Māori guides accompanied the surveyors on these expeditions which

were challenging, even dangerous. Kehu was highly acclaimed as a man of

exceptional physical, intellectual and human qualities. The exploring parties

embarked on lengthy journeys, food was hunted, fished or foraged and fernroot

became the staple diet. Diaries record adverse weather, treacherous river

crossings, precipitous bluffs, riptides, ill health and starvation. Māori guides

had bushcraft and survival skills, snaring birds, catching eels, building

shelters, fire lighting and manoeuvring waka. They also facilitated

communication with local Māori and sought food and lodging.

Aorere

Valley, C Heaphy, 1843

F Tuckett, J S Cotterell, T Brunner,

C Heaphy and W Fox owe their successes to the service of their guides. Most

guides were of Kurahaupo iwi – Tumatakokiri, Apa, Kuia or Rangitane, and were

hired to the British surveyors by their chiefs. Kehu, Pikiwati and Tau undertook

some of the most significant expeditions. In 1846, Brunner and Heaphy set out to

map a coastal route from Mohua to Arahura, an expedition anticipated to take no

more than three months. On the 17th of March

Brunner, Heaphy and Kehu sailed from Nelson to Aorere where they remained at the

pa for two days waiting out the bad weather. They trekked to Pakawau pa and

engaged Tau, mokai to Hemi Kulu Matarua.

This west coast route was hazardous

due to swift rivers, tidal surges and steep cliffs rising from the beach. Along

the way the party passed the remains of a sealing station, wrecked vessels and

scenes of utu – revenge killings. However, they were offered Māori hospitality

and at Taramakau they observed the craft of grinding and polishing pounamu –

greenstone. Tau was welcomed home by his relatives at

Kararoa.

Charles Heaphy, The Nelson Examiner, 1846:- The whole population of the village of Kararoa consisting of one man, seven women and a tail of twenty children, now ran down to the beach, hailing us with shouts of Naumai Naumai – welcome, welcome. While Etau, the ragged rascal, strutted along before us with his tomahawk in his hand and as proud as any two peacocks at having conducted the first white men to Araura. The trip was hampered by heavy rainfall, rivers in flood and a shortage of food. They arrived back in Pakawau on the 7th of August after trekking for five months.

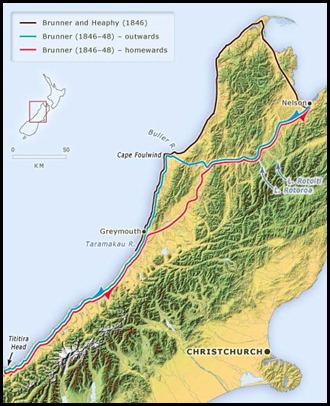

Side Note. On the 11th of December 1846, Brunner, accompanied by Māori guides Kehu and Pikewate and their wives, set off on the longest feat of exploration in New Zealand history. The party were away for almost eighteen months. They endured constant wet weather and frequent periods of starvation. The routes they took are marked on this map.

The Sea. Collingwood’s name is symbolic of the sea’s importance to early European settlers and their descendants. Admiral Lord Collingwood was second-in-command at the Battle of Trafalgar in 1805. After Admiral Lord Nelson was killed, Collingwood completed the British victory over Napoleon’s French/Spanish fleet. When gold fuelled the growth of the little settlement of Gibbstown in the late 1850’s, and grandiose plans for a town were drawn up in London, the proposed town was to be named after Cuthbert Collingwood and the streets for ships, Admirals or nautical terms. Collingwood in Golden Bay was intended to stand alongside Nelson in Tasman Bay. The sea was Collingwood’s highway in early settler and gold rush days, for no road crossed the Taranaka Hill. Even when a road was created sea traffic was, for many years, the most economical way to move provisions and passengers in and out. Nelson is only sixty five nautical miles away and scows, schooners, barges and coasters traded in and out of Golden Bay. There was plenty to ship in those early boom years with settlers, miners and supplies coming in and, as local industry developed, timber, coal, flax, butter and cheese going out. In January 1858 Collingwood was declared a Port of Entry with a Harbourmaster and Customs Officer. The first wharf, at William Street, was built in 1859 and in the late 1860’s the steamer Lady Barkly began over fifty years of service in the town. Exports from Aorere harbour continued into the 1960’s but the silting of the estuary, the loss of many coastal traders in the Second World War years and the rise of road freight affected the viability of the port. The Collingwood Harbour Board was disbanded in the late 1950’s. Collingwood’s last wharf – Ricketts, was used by fishing trawlers until its demolition order from Golden Bay County Council several years later. Now Collingwood’s seaway is patronised by mussel farmers, recreational fishers, boaties and whitebaiters. All that remains of this chapter are tiny, rotting posts in the tidal estuary.

ALL IN ALL A RICH AND

COLOURFUL

PAST |