Riches and Beauty

Beez Neez now Chy Whella

Big Bear and Pepe Millard

Sat 30 Jan 2016 23:27

|

A Land of Riches and Beauty –

the Mines

Mount

Heemskirk, north of Zeehan. Both names are taken from Tasman’s two

ships.

In November 1642, only two days out

from Tasmania’s West Coast, Abel Janszoon Tasman wrote in his journal that his

compasses were not working as they should, he then noted, “There might be mines

of loadstone about here”.

Coincidental or not,

Abel Tasman’s supposition proved to be true. Two days later his crew sighted the

mountains of Tasmania’s West Coast. Two hundred and fifty years later, following

the discovery of enormous lodes of tin at Mount Bischoff, the slopes of Mount

Heemskirk were discovered to be black magnetite, nearly sixty six per cent iron.

The surrounding region became famous for a spectacular number of mining booms

from Mount Bischoff in the north to Mount Lyell in the south. Prospectors came

from all over the world in the hope of finding an El Dorado. While the gold in

any large quantity proved elusive, they discovered enormous quantities of tin,

copper, silver, lead, iron and rare minerals such as osmiridium.

Few regions in the world have been

blessed with so much mineral wealth in such a small area, surrounded by

magnificent scenery. In 1923, local writer and mountaineer Charles Whitham wrote

a small book to promote Western Tasmania to tourists. He included chapters on

the region’s minerals, geology, history, flora, fauna and topography. He called

it “A Land of Riches and Beauty”. The title refers to much more than minerals

and scenic views. Whitham begins his book with a reference to deeper riches, the

food for the soul. He describes the vistas of the

mountains, the valleys, the forests and the deep, dark rivers. And then, quoting

the poet William Wordsworth he writes “There is no doubt that we see with the

soul and not the eyes.....”

We left Queenstown and climbed the steep road to

the Queenstown Lookout, the colours of the rocks were quite

something. After enjoying the view we settled to reading the information

boards, learning about mining in the area.

The Iron Blow: In January 1883, while following mountain creeks upstream in the

search for reef gold, the McDonough brothers and ‘Steve’ Karlson camped on the

brow of the high ridge between Mount Owen and Mount Lyell. They noticed a large

outcrop of gossan – the kind of oxidised rock formation prospectors look for as

an indication of rich mineralisation below the surface. They called it “Iron

Blow”.

The blow jutted high above the

surface. Strewn down the mountainside were large iron boulders as if there had

once been a massive explosion from deep below the earth’s

crust. The prospectors found some gold in

the creeks below, but initial attempts at mining ‘The Blow’ proved

futile.

Throughout the mis 1880’s the mine

struggled as the McDonough’s and Karlson slowly carved away the gossan outcrop,

convinced that reef gold lay beneath. In 1888 a new company was formed, issuing

new shares and the amount of gold recovered increased, the costs of running the

stamper and freighting the gold to the nearest port at Strahan rendered the mine

unprofitable. Despite the rich potential of ‘The Blow’, in 1890 the directors

decided to wind the company up.

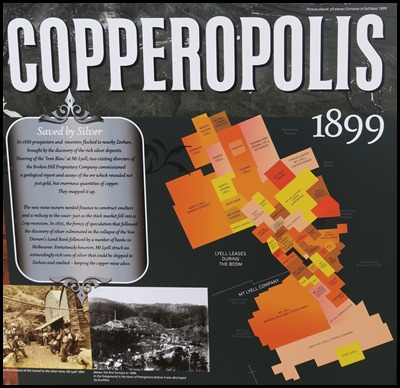

Lyell

leases during the boom.

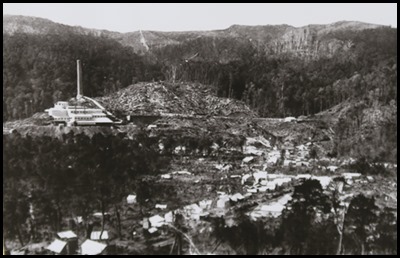

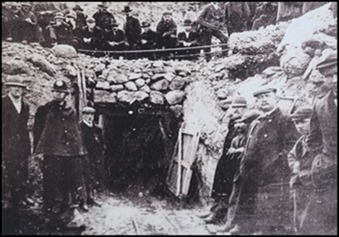

Miners

gathered at the entrance of the tunnel to the silver mine, Mt Lyell 1894. The first furnace in 1896. In the foreground is the town of

Penghana before it was destroyed by bushfire.

In 1888 prospectors and investors

flocked to nearby Zeehan, brought by the discovery of the rich silver deposits.

Hearing of ‘The Blow’ at Mount Lyell, two visiting directors of the Broken Hill

Proprietary Company commissioned a geological report and assays of the ore which

revealed not just gold, but enormous quantities of cooper. They snapped it

up.

The new mine owners needed finance to

construct smelters and a railway to the coast – just as the stock market fell

into a deep depression. In 1891, the frenzy of speculation that followed the

discovery of silver culminated in the collapse of the Van Diemen’s Land Bank

followed by a number of banks in Melbourne. Fortuitously however, Mount Lyell

struck an astoundingly rich vein and smelted – keeping the copper mine

alive.

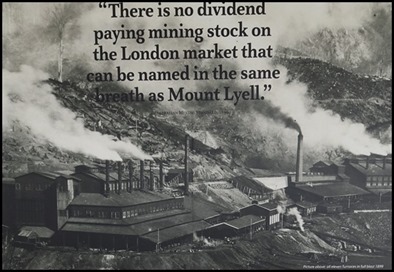

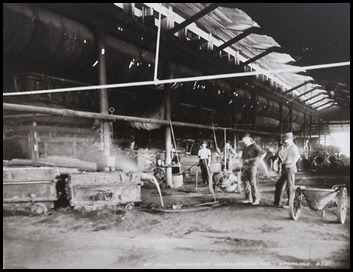

All the furnaces

working at full blast in 1899. Interior of one of the

furnaces.

By 1896, the investment climate had

recovered. The company was able to raise enough finance to complete its

ambitious building program. In June that year, the first two smelters were lit.

Four months later it was reported in the London press that ten furnaces would

produce an annual profit of nearly eight hundred thousand pounds. Mount Lyell

was touted as the greatest copper mine in the world.

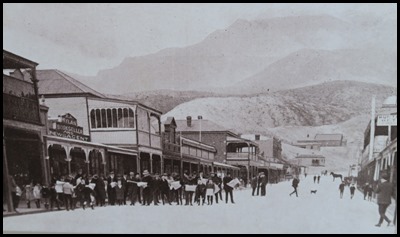

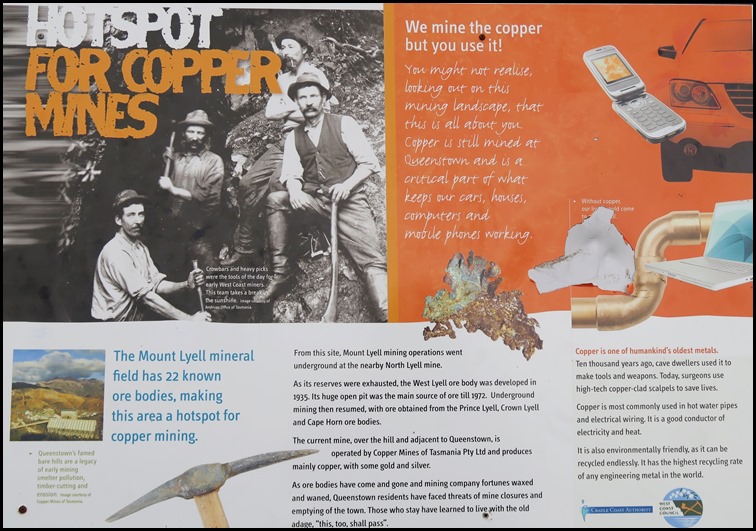

Queenstown became a hotbed of

prospectors, investors and swindlers. The Tasmanian press called it

‘Copperopolis’ – the copper city.

‘Copper’ and ‘Mount Lyell’ became

magic words, Prospectuses of the new companies that sprang into existence all

stressed their proximity to the ‘mother lode’ at My Lyell and all of them used

the word ‘Lyell’ in their name. In the rush even

geographical proximity to the famous Iron Blow was deemed unnecessary. Mines

appeared as far away as Strahan and Dundas carrying the ‘Lyell’

name.

The

landscape.

If we had been standing here a

hundred years ago, the entire landscape around us would have been entirely

denuded. The image of billowing smokestacks was a symbol of pride, progress and

‘getting ahead’. It was even reproduced as a picture postcard.

The smoke however, was a toxic gas –

sulphur dioxide. It clogged the air and left the surrounding landscape covered

in poisonous yellow dust. It even changed the local climate.

In still weather a pea-soup blanket

of yellow fog could be seen from Strahan. Here, in the valley, workers would

carry hurricane lamps to get them to and from work in daylight hours.

There were frequent reports of the pungent fog causing workhorses to bleed from

their noses.

While the surrounding forests were

cut down as supplementary fuel for the smelters, what remained was killed by the

sulphur. Within a few years the slopes of Mount Owen, Mount Lyell and all the

surrounding hills were devoid of any vegetation. With Queenstown’s high annual

rainfall, the shallow topsoil was quickly eroded leaving bare rock.

By 1921 the pyritic smelting process

had been superseded by new flotation technologies. The furnaces were gradually

replaced.

The bare hills became a magnet for

artists seeking to capture the pink and yellow hues of the mountain range. There

were even rumours of local anxiety over losing this man-made ‘attraction’. Slow

regrowth has taken hold in many of the valleys but with no topsoil on the higher

slopes it is clear that large areas of the mountain slopes and the surrounding

hills will remain bare rock for generations to come.

Copper

pyrites [from the Greek ’pyrites lithos’ meaning “stone of fire” –

flint.

The worthless fool’s gold that the

first prospectors found in this area was pyrites – iron sulphide. It is

worthless for a gold digger but of great value to a metallurgist. From ancient

times the incendiary nature of the element sulphur was well known. In

the Bible it is called brimstone – meaning ’burn stone’. As the science of metallurgy developed in the late 1800’s the

common presence of pyrites in many ore bodies generated world-wide interest in

using it as a ready-made fuel for smelting. For the mine at Mount Lyell,

situated in a remote location far from its markets and supplies of coke, the

potential for the process to increase the viability of the mine was

immense.

Robert

Sticht in his library in Penghana.

The key to Mount Lyell’s success was

a process called pyritic smelting. Rather than importing expensive coke to fuel

the furnaces, the process utilised the heat generated by the combustion of

sulphur in the pyrite.

The Company had approached Robert

Sticht, a world authority in pyritic smelting. Sticht’s first pyritic smelter in

Montana was a failure, but spurred on by the experience, he continued to

experiment. When the Mount Lyell Company approached him in 1883, samples of ore

convinced him the Tasmanian mine would make pyritic smelting an unqualified

success.

It did. When Sticht lit the furnace

on the night of the 25th of June 1896 and tapped the furnace for molten copper,

the workmen could hardly keep up with the flow. The company’s share price

skyrocketed. Sticht was appointed mine manager on a princely income of five

thousand pounds per year.

He left twenty five years later a

very wealthy man. However, the legacy of a quarter of a century of pyritic

smelting can still be seen all around us.

People anxiously

waiting for survivors to emerge. People reading the

newspapers to learn of loved ones, friends and workmates.

Often shrouded in mist and rain, the

raw beauty of the mountains surrounding this valley hides a tragedy that shocked

the nation. On Saturday the 12th of October 1912 a fire broke out in the Mount

Lyell mine at the seven hundred feet level, trapping men there and in the levels

below. Initially there was little urgency.

The timber supports throughout the

mine were waterlogged beams of King Billy pine – and widely believed to be

fireproof. By late afternoon seventy three men had made their way to safety. It

was then realised slow burning fire was smouldering in the timbers and producing

a small amount of smoke but large amounts of deadly carbon dioxide. Over the

next two days a number of heroic rescue attempts were made. Bodies were found at

the seven hundred feet level and hope was fading for the other men when a

message was received from a signal gong attached to a rope that had been lowered

to the thousand feet level.

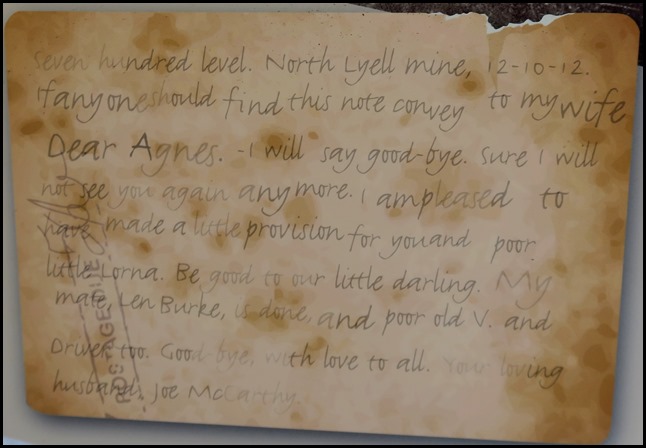

A note found from

one of the men at level seven hundred.

“Forty men in forty stope. Send food

and candles at once. No time to lose. J. Ryan”.

The forty men had survived on the

compressed air nozzles that fed the diamond drills. In record time, fire

fighting and rescue equipment had been sent from Ballarat. On Wednesday, five

days after their entombment, the first forty survivors in forty stope [a

step-like working in a mine] reached the surface. Forty three men including some

of the rescuers, were not so lucky.

A funeral

train carries rows of coffins as photographers watch from their vantage

point.

Why the fire started remains

controversial. The inquest was inconclusive. While noting circumstantial

evidence suggesting the fire had been deliberately lit by a disgruntled worker

whose brother had been killed in a rockfall, no-one was ever charged. Although

there were allegations of negligence, the Company was exonerated. After inquiry,

the investigating Commissioner was employed by the Company.

Writing forty years after the event,

in The Peaks of Lyell, historian Geoffrey Blainey suggests that the

rise of trade unionism on the west coast, and the lack of preparedness for such

disasters by mining companies at the time contributed to the tragedy. An

alternative view is provided by Peter Schulze in An Engineer Speaks of

Lyell who argues that the most likely cause of the disaster was an

electrical fault.

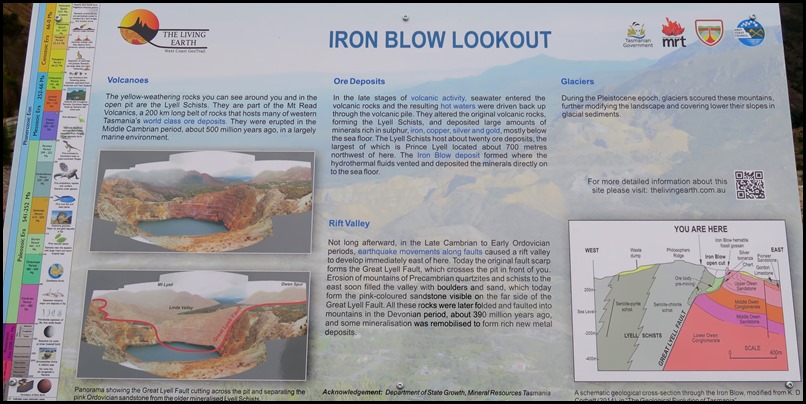

Our next stop was at the amazing Iron Blow Lookout.

The view from the

end of the platform.

Straight to the information boards.

Causing a stir. “........this

mine will prove one of the world’s wonders, and the holder of a hundred shares

can consider he is provided with a moderate income for life.” – Australian

Mining Standard, July 1897.

Mining riches or inspiring place?.

Powerful forces beyond our wildest imaginings have conspired to produce the

copper, gold and silver riches of Mount Lyell – along

with ruggedly beautiful terrain that can leave us awestruck.

The landscape we see here may have

been carved by miners during more than a century but first it took nature

millions of years to create it. Minerals were formed within a volcanic island

about 550 million years ago. Hot geothermal springs concentrated them within

young volcanic rocks.

Rocks were buried by sediments in a

shallow sea that protected them from erosion. This landscape was then subjected

to the upheaval of intense heat and pressure, hardening and contorting the rock

layers. The nearby mountain peaks of Lyell and Owen – and others in the Coast

Range – are the remains of sediments.

Fair worksite or living

hell?

The Mount Lyell Mining and Railway

Company came to be known for a groundbreaking employee welfare scheme. However,

voices from the past show that – just like today – opinions on a workplace are

often a matter of perspective.

Bricklayers petition for a wage rise,

1895. “We beg to state that nothing of any arbitrary or dictatorial spirit

is intended but simply an honest and honourable appeal to you for a wage

commensurate with our toil, intelligence and climate. Whatever determination you

may arrive at, we are sure it will be on a fair and equitable basis, and to

which you may rely we will cheerfully and without prejudice,

abide.”

Article by militant worker in the

Communist newspaper, The Workers Weekly 1930: “We

have to work out in the weather with no provisions made for the wet, either that

or take the sack. The slaves underground and on the smelters on afternoon shift

get the same pay..... The class of bonehead that stays here has nothing on the

brain but the job.... There is no accommodation excepts the pubs. Boarding

houses are very scarce. There are not many unemployed and I would not advise

anyone to come here as the company’s motto is to ‘weld the weak and test the

strong’.”

Though hemmed in by mountains,

Queenstown stays in touch with the rest of the world through modern roads and

communications – but in the early years, it was a long way from

anywhere.

Behind us the

ore-rich rocks showed many colours.

In front of us, the scarred landscape.

Excerpt from 1922 program for Back to

Gormanston celebrations: “Twenty-five years ago,

when the tent-dwellers in the Queen Valley [later Queenstown] were all dressed

up, they had no other place than Gormanston to go if they wanted a legal drink,

a postage stamp or a shirt..... they had to hop over the hill and satisfy their

wants at Lyell, as Gormanston was then known.”

The settlement in the distance is

Gormanston. It is living proof that our destiny can unravel in an instant. Known

locally as ‘Gormie’, it is one of a string of local towns created in mud,

forests, valleys and mountains, only to be destroyed by human

weakness.

They were the product of a bitter

feud between two mining men and their rival companies. The men, James Crotty and

Bowes Kelly, had by the end of the 1880’s each built their own major mine,

smelters, railway, port and series of towns, housing a total of 10,000

people.

Crotty had the richest mine, North

Lyell, which suffered from poor management and financial blunders. Kelly’s Mount

Lyell Mining Company had astute leadership but diminished ore reserves. A merger

was inevitable. Locals waited nervously to see which railway, port and towns

would die. The agreement was signed in 1903 and went against the North Lyell

Company.

Gormanston State

School, destroyed in a storm, 1950’s.

The town of Darwin, south of here,

was abandoned overnight, Crotty was soon deserted – its site is now below

man-made Lake Burbury. Pillinger, at Kelly Basin, with brand new wharves,

houses, shops and brickwork lingered for a

few years. Linda, sister town to

Gormanston, [Linda Post Office opened on the 18th of December 1899 and closed in

1966] is a ghost town, later we would drive past the ruins of the Royal Hotel in the Linda Valley. Gormanston despite

much adversity, has managed to survive with a

permanent population of 167 [2006 census]. New recreation opportunities rather

than mining are now the life blood of the communities. Queenstown became the

area’s main town and Strahan its port. But it could just as easily have been

Gormanston or Pillinger.

The rock at the

Lookout, the plaque reads: The Mount Lyell

Mine “The Iron Blow”.

This ground was first pegged by

Mick and Bill Macdonough and Steve Karlson in November 1883 in their search for

gold. The lease was worked for gold with limited success until it was recognised

as a copper mine and bought by Bowes Kelly and William Orr in 1891. In March 1893 they formed the Mount Lyell Mining and Railway

Company Limited. A lucky bonanza of high grade silver ore was a major factor in

financing Mount Lyell while the copper smelter and the railway to Strahan were

built. From 1893 to 1895, 849 ton of ore was sold assaying 21% copper and 1023

oz. of silver per ton. Subsequently the Blow was worked until 1929 and yielded

5. 497,468 ton of ore assaying 12% copper , 2 oz. silver per ton and 0.0065 oz.

gold per ton.

Commemorating the Lyell District

Centenary November 1983.

ALL IN ALL QUITE A

STORY

FASCINATING HISTORY

|