Rorke's Drift Museum

|

Rorke's

Drift Museum

Rorke’s Drift

Museum.

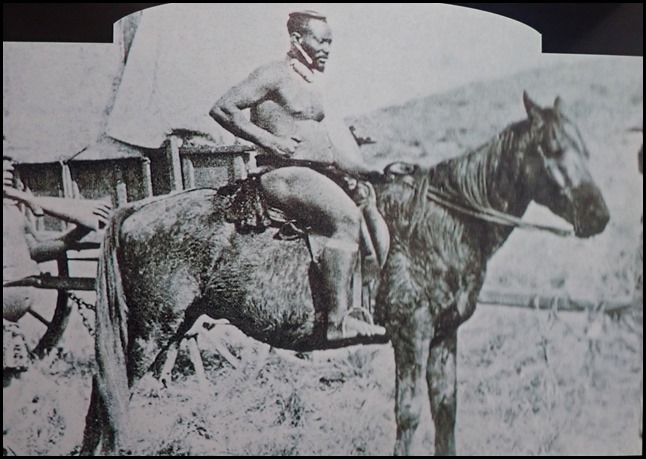

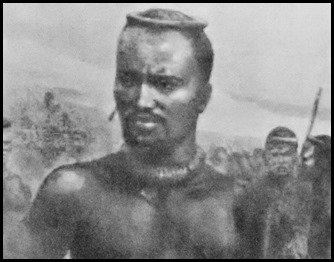

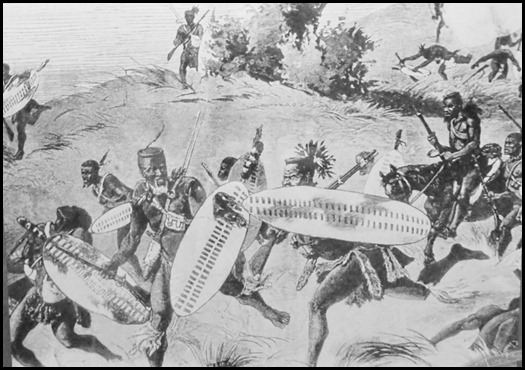

We turned right through the door to

learn about the Zulu warriors. Prince

Dabulamanzi, King Cetshwayo’s younger half-brother, led the Zulu (uNdi)

force attacking Rorke’s Drift. In crossing the Mzinyathi (Buffalo) River, this

aggressive and impetuous man was flaunting tha king’s instruction that the Zulu

were not to enter Natal. Probably Dabulamanzi’s royal status saved him from

retribution. He lacked military skills. and researchers have questioned the lack

of a concerted Zulu assault when the British defenders were stretched. The

killing of a mounted Zulu in the initial assault might explain poor Zulu

tactics.

Dabulamanzi served at Ginginglovu and Ulundi (as did elements

of the Rorke’s Drift amabutho), and supported King Cetshwayo (1884 – 1913)

during the post-war upheavals in Zululand. He was assassinated in

1856.

The British public’s introduction

to the Zulu commander Prince Dabulamanzi was in the Illustrated London News on the

12th of April 1879.

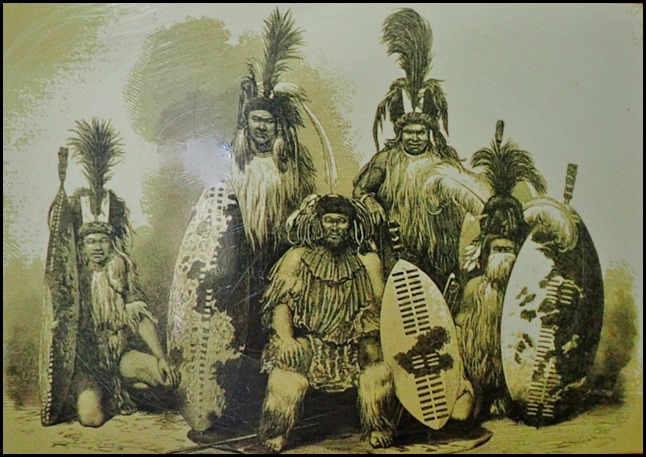

The amabuthi (age regiments): The

Age regiments, initiated by Inkosi Dingiowayo had its roots in the grouping of

boys into age groups for circumcision. During the reign of King Shaka the

circumcision ritual was abolished, and replaced by a system which grouped boys

of similar age into regiments (amabutho), to which they belonged for the rest of

their lives. At the age of about 16 years, boys would be summoned by the king

for service at his residence, i.e. herding cattle, preparing fields and the

practise of basic military skills.

After about two years this group

of cadets was formed into a regiment. They were given their own regimental name

and their specific uniforms. Each regiment was

commanded by two officers (izindung) and could number up to 2000

men.

They had to serve the king for

military and economic purposes until he permitted them to marry (at about 30 in

King Shaka’s time), and sew on their head ring. This was the sign that they were

mature men.

The army had to undergo many

rituals before and after doing battle. Rituals before battles ensured that the

warriors would be successful. Several ceremonies were held in which the warriors

were doctored with various medicines to make them strong. From this time and

until the battle was fought the warriors were not allowed to enter into normal

social activities (i.e. no contact with women etc.).

After the battle the warriors

were considered polluted by umnyama, released by the violent shedding of blood.

They had to undergo several cleansing rituals in order to rejoin normal

society.

Firearms: As early as in King

Shaka’s (1816 – 1828) and King Dingane’s (1795 – 1840 days small groups of white

gunmen were attending to certain actions with the Zulu army. The first muskets

were imported to Zululand during King Dingane’s reign. But most of the weapons

were of poor quality and the warriors were not trained to use them

properly.

In the 1850’s when King Mpande

(1828 - 1884) allowed hunters and traders to access his kingdom guns became an

increasingly important element for the army as a symbol of political

power.

Guns were often used as payment

for hunting rights. In the 1860’s John Dunn (adviser to King Cetshwayo) was

officially allowed to import large quantities of firearms through

Mozambique.

Between 1872 and 1877 about

60,000 firearms were legally imported to Natal.

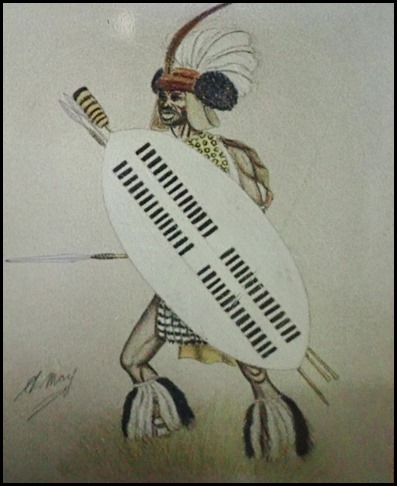

The

Uniform: A warriors uniform consisted of a shield, spears, knobkieries,

leather coverings and various headdresses and feather

adornments.

The Spear: The weapon most

commonly associated with King Shaka is the stabbing spear. Legend has it that

all throwing spears were collected and reworked into stabbing spears by smiths

across Zululand, and issued to troops, who were then trained in hand to hand

combat. It is however more likely that a stabbing spear would have been carried

in addition to a number of throwing spears. The stabbing spear name (ikwa)

derives from the sound made when the blade is withdrawing from flesh. The

assegai was also used as a general cutting tool, and for the slaughter of

cattle.

The Shield: The Zulu have names

for a number of shields, ranging in size from the large war shield (isihlangu),

to small dancing shields. The shield is cut from cowhide and is secured to a

central supporting stick.

During King Shaka’s time the

shield was turned from a defensive into an offensive weapon. Soldiers, in close

combat would use their shields to hook away the opponents shields, exposing the

enemy’s flank to a stabbing spear. The shield was seen as a symbol of peace and

protection, and was ‘doctored’ to give it magical protective properties. Each

regiment was given a shield with specific colours and

patterns.

The Knobkierie: The large headed

knobkierie was made from a variety of hardwoods. Used as a throwing weapon, but

mainly for striking, it was seen as a symbol of mercy, a way of ending

suffering.

Tactics: King Shaka’s main

principle in attack was to encircle the enemy, forcing a situation of hand to

hand combat. This battle formation was represented by the head of an ox and

encompassed four formations.

Veteran regiments made in the

centre or chest, of the formation. A reserve force was positioned behind them.

The chest would move towards the enemy and then withdraw. The enemy believing

this withdrawal would pursue. At this point the chest would once more attack,

causing confusion in enemy ranks. In the meantime, two horn formations

comprising younger troops, would encircle the enemy flanks.

The Isiqu: Anonymous Valour: It

is difficult to compare the VC and the informal Zulu acknowledgement of

exceptional bravery, but consider the following: The amabutho who fought at Rorke’s Drift, mostly married men in

their 40’s, had been on the move, at speed and with little sustenance for five

days.

Their repeated assaults against

superior firepower continued into the night (unprecedented in Zulu warfare) and

only ceased after 12 hours, with huge losses. If 11 VC’s were awarded to the

defenders, then how many Isiqu were owed to the attackers?

“When the fight moved to below

Jim’s house we gathered in the bush and rushed at the sacks again and again,

thrusting and digging with our assegais. Although we got close to the English

here, the battle was so fierce that we had to wipe the blood and brains of the

killed and wounded. We climbed over our fallen brothers. It was fearful,

especially when the soldiers stabbed at us with assegais tied to their guns.”

(Fictionalised account) from Vusi kaNzama uDloko ‘ibutho’ (uNdi

corps).

“It seemed that no one could face

the guns without being struck. Some of us decided to seek a safer place in the

rocks behind Jim’s. From there we could shoot at the English with our own guns.

I saw some white men fall, especially amongst those with their back to us.

(Fictionalised account) Bhekizitha kaNdlovu uThulwana ‘ibutho’ (uNdi

corps).

“You went to dig little bits with

your assegais out of the house of Jim, that had never done you any harm!” (Zulu

response to the abortive raid.

After lingering briefly on

Shiyane, the exhausted and dispirited impi withdrew. They had been on the move

since dawn on the 22nd but had failed to overcome the British bullets, bayonets

and barricades at ‘kwaJim’. Some dead and wounded were carried away but most

lay, in the words of a defender, “as if literally mown down.” The survivors

dispersed to their homes and few were prepared to reassemble at oNdini on King

Cetshwayo’s orders.

The British: The Rorke’s of

Rorke’s Drift:- Rorke’s Drift was named after James

Rorke who settled here with his wife Sarah in

1849 to farm and trade. During the 26 years James spent here until his death in

1875, he became actively involved within the community. He was the Government

Border Agent, Justice of the Peace and First Lieutenant in the Buffalo Border

Guard. He became well known amongst the

Zulu. They called this place “Kwa Jimu” (Jim’s Place).

Rorke broke down the steep banks

of the Mzinyathi (Buffalo) River, where it was easiest to cross, to improve

travel between Natal and Zululand. This became known as Rorke’s

Drift.

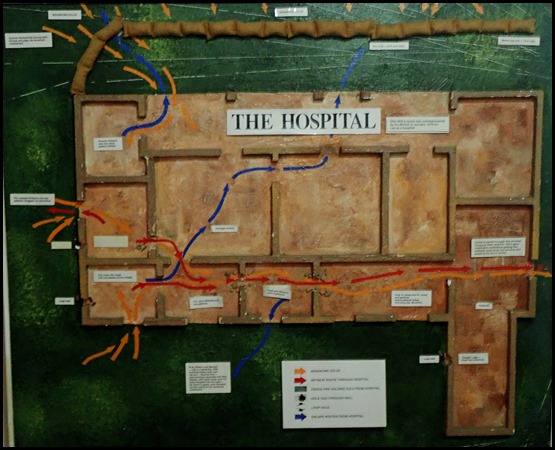

In the next room we saw a diorama of

a patient in bed, rifle at his side, bullets scattered about the bedding.

The Hospital Building: Reverend Otto Witt’s original mission house was

modified by the British during their fortification of the post on the 22nd of

January 1879. It was destroyed in the Battle of Rorke’s Drift. After the

battle it was pulled down and the stones were used to build Fort

Bromhead.

In late 1879 the Swedish Mission

returned. In 1880 the present building was constructed according to Witt’s

specifications. Stones from the original house may have been used in the

structure.

Excavations have revealed that

the pre-1880 building was smaller than the present one. The existing building

has many of the original features, including the windows. Other features

such as the thatched roof have been altered. The archaeologist's sketch shows

areas which were excavated in 1988. Quadrant 32 remains open for

viewing.

In the left corner (next to the patient above) a

soldier is crawling through a hole made through to the next room, he has followed a wounded fellow soldier.

In this room a diorama shows a soldier filling a mealie bag and others planning the next move.

Behind us, as we entered the room, a

cupboard where an injured soldier is seen in hiding.

Bear got in with him....

Along the left wall is a dramatic

scene of soldiers behind the mealie bags with a Zulu warrior

on the attack.

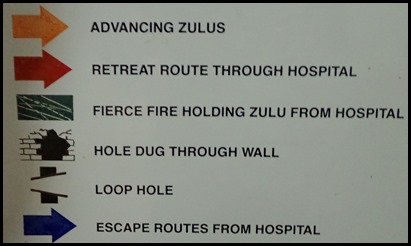

A plan on the far

wall with key.

The struggle for control of the

hospital was a desperate one. The building, defended by a handful of men and

patients, was barricaded with mealie bags and loopholed.

The Zulus attacking the hospital

were decimated by rifle fire from the biscuit box line, but eventually managed,

at great cost, to enter the hospital. They set fire to the thatch, but for some

time this did not burn properly as the grass was so tightly packed. A

claustrophobic struggle ensued.

The defenders retired room by

room, bringing out as many sick as possible. Occasionally they were forced to

smash holes through walls to escape as no interleading doors existed. Walls

built of soft sunbaked brick proved a saving grace, as did the narrowness of

doorways. The Zulus found these and all other bottlenecks stoutly defended until

the last moment.

Finally the defenders reached a

window that overlooked the inner barricade. There patients were helped through

by a few courageous men who remained disciplined and cool in the exposed and by

then abandoned outer perimeter.

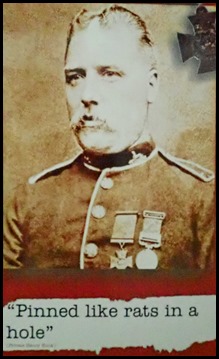

We saw reports and pictures of

individual acts of heroism. “From perfect quietness to intense excitement”

Private Henry Hook VC 2/24th.

Heroic Cook: The fierce contest for the hospital had

its heroes. On the Zulu side regrettably remain anonymous, on the British side

they are known. An unlikely hero was the unassuming, humble cook, Private Henry

Hook. He held off the Zulu in hand to hand combat and assisted evacuating the

hospital patients.

“.... John Williams held the

(other) room with Private William Horrigan for more than an hour, until they had

no cartridge left. The Zulus then burst in and dragged out Joseph Williams and

two of the patients, and assegaled them. It was only because they were so busy

with slaughtering that John Williams and two of the patients were able to knock

a hole in the partition and get into the room where I was posted. Horrigan was

killed.”

His exceptional bravery was

subsequently rewarded with the Victoria Cross. On receipt of this supreme

decoration for gallantry he commented, rather typically, “...until then I had

scarcely ever thought about the Victoria Cross....”

I happened to be reading about

Private Hook when a guide came in with a couple of men being shown around. The

guide pointed to Private Hook’s South African Campaign Medal (seen to the right

of the VC above). He said that the last time a general medal came up for auction

it sold for six thousand dollars. Each medal has the recipients name engraved

around the edge, and the last Rorke’s Drift medal sold for one hundred and

thirty thousand dollars. He went on to tell the tale of Tiger, Pip or Jack – he

answered to all three. He was the posts faithful dog who barked warning when the

Zulu approached, he too was awarded The South African Campaign Medal, I wonder

what price this unique medal would sell for. Brave little fellow.

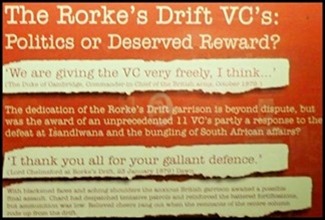

The Rorke’s

Drift VC’s: Politics or Deserved Reward ? “We are giving the VC very

freely, I think....” (The Duke of Cambridge, Commander-in-Chief of the British

Army, October 1879).

The dedication of the Rorke’s

Drift garrison is beyond dispute, but was the award of an unprecedented 11 VC’s

partly a response to the defeat at Isandlwana and the bungling of South African

affairs?

“I thank you all for your gallant

defence.” (Lord Chelmsford at Rorke’s Drift, 23rd of January 1879)

Dawn.

With blackened faces and aching

shoulders the anxious British garrison awaited a possible final assault. Chard

had dispatched tentative patrols and reinforced the battered fortifications but

ammunition was low. Relieved cheers rang out when the remnants of the centre

column rode up from the drift.

B Company

2/24th.

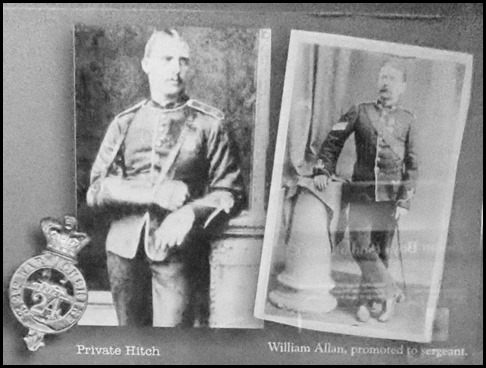

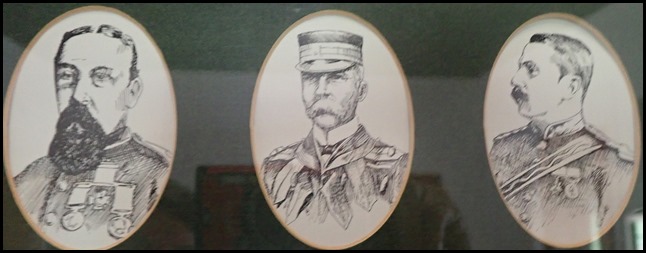

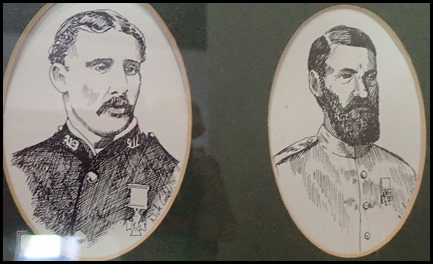

A VC Selection: Corporal William Allan and Private

Frederick Hitch (2/24th).

Allan and Hitch kept the exposed

areas between the hospital and inner barricade clear during the evacuation of

the patients. Both were severely wounded but stuck to this task, Hitch borrowing

Bromhead’s revolver when his shoulder was shattered by a bullet from the Shiyane

terraces. Both received their VC from Queen Victoria. Hitch’s award was later

stolen and a duplicate presented by King Edward VII in 1905.

Sad Endings: Privates William and

Robert Jones (2/24th) and Corporal Ferdinand Schiess (3NNC).

William Jones, a Frontier Wars

veteran, fought alongside Private Robert Jones VC in the claustrophobic hospital

struggle. Schiess had served in the French Army (1871 –6) and was recruited into

the Natal Native Contingent following service in the Eastern

Cape.

Schiess had been the only Rorke’s

Drift defender present at Sihayo’s stronghold where he was wounded in the foot

hence his presence at the post. His dramatic exploits at the northern barricade

earned him the VC.

The award was, however, no

guarantee of prosperity, Schiess died at sea, destitute in 1802, and in 1803

William Jones pawned his VC for 6 pounds. Robert Jones took his own life in

1806.

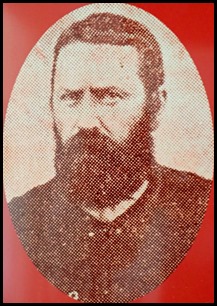

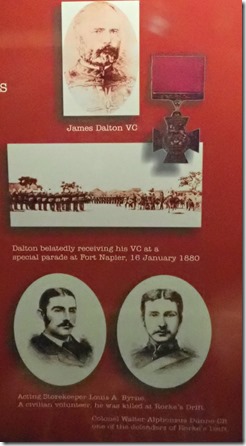

The commissariat

and transport staff: Dunne, Byrne and Dalton.

Only after considerable delay,

and public pressure, was the cool determination and courage of these men

recognised.

Dalton, a veteran of 20 years

service, applied his knowledge of prepared defences in response to the crisis at

the post. He inflicted heavy losses along the southern perimeter during the

initial attack and saved the life of a private about to be assegaled. When

wounded in the back by a sniper he casually handed his rifle to Chard. (The

picture in the middle, above, is Dalton belatedly receiving his VC at a special

parade at Fort Napier, 16th of January 1880)/

Dunne. In the battle Dunne’s most

notable feat was the active supervision of the building of the redoubt while

exposed to Zulu attacks.

Byrne. On the 22nd of January

Louis Byrne appears to have supervised the construction of the biscuit-box

barricade bisecting the defence, and was shot through the head while assisting a

wounded NCC corporal (Scammel).

Reynolds, in charge of the field hospital at Rorke’s Drift,

had observed the initial approach of the amabutho from the summit of Shiyane.

Throughout the action he attended the wounded, under fire, on the storehouse

verandah. He was one of the few Rorke’s Drift veterans to serve at

Ulundi.

Mabin.

‘The fighting clerk’, was an unlikely combatant at Rorke’s Drift. He served in

the Corps of Military Staff Clerks, and he had presumably been seconded to the

supply depot at the drift. He acquitted himself well in the battle, but his

service went largely unnoticed.

Smith.

The popular image of the Reverend George Smith is of an imposing, bearded figure

handing out ammunition while exhorting wild biblical phrases. In fact, he would

have left with Otto Witt if his horse hadn’t been missing.

On the 4th of February he read

the burial service for Melvill and Coghill at Fugitives’ Drift, and accompanied

Chelmsford to Ulundi. Smith was appointed Chaplain to the Forces in recognition

of his service at Rorke’s Drift but was reputedly offered the choice of a

VC.

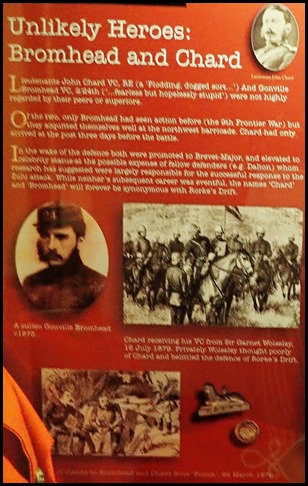

Unlikely Heroes: Bromhead and

Chard.

Lieutenant

John Chard VC, RE (top right above) - (a ‘Plodding, dogged

sort...’) And Gonville Bromhead VC, 2/24th (‘.....fearless but hopelessly

stupid’) were not highly regarded by their peers or superiors.

Of the two, only Bromhead had

seen action before (the 9th Frontier War) but they acquitted themselves well at

the northwest barricade. Chard had only arrived at the post three days before

the battle.

In the wake of the defences both

were promoted to Brevet-Major, and elevated to celebrity status at the possible

expense of fellow defenders (e.g. Dalton) whom research has suggested were

largely responsible for the successful response to the Zulu attack. While

neither‘s subsequent career was eventful, the names ‘Chard’ and ‘Bromhead’ will

forever be synonymous with Rorke’s Drift.

In the middle of the picture above is

A sullen Gonville Bromhead c.1873. The next

picture shows Chard receiving his VC from Sir Garnet Wolseley, 16th of July

1879. Privately Wolseley thought poorly of Chard and belittled the defence of

Rorke’s Drift.

Of the battle BBC History says: Within days of Rorke's Drift, Chelmsford was urging the speedy completion of the official report because he was “anxious to send that gleam of sunshine home as soon as possible.” When it finally arrived, he added two names to the six recommended VCs - the names of lieutenants Chard and Bromhead. Many of their fellow officers were amazed by these two additions. One senior officer wrote: “Bromhead is a great favourite in his regiment and a capital fellow at everything except soldiering ... He had to be reported confidentially as hopeless.” Another described Chard as “a most useless officer, fit for nothing.” In truth, the real hero of Rorke's Drift was Commissary Dalton. It was Dalton who persuaded Chard and Bromhead to remain at Rorke's Drift when their first instinct was to abandon the post, and it was Dalton who organised and inspired the defence. But Dalton, an ex-NCO, came from what was considered the wrong background, and was ignored for almost a year. He was eventually awarded a VC after intensive lobbying by the press - but not until January 1880, by which time the celebrations had died down.     In the next tiny room was a huge model that really shows what the defenders were up

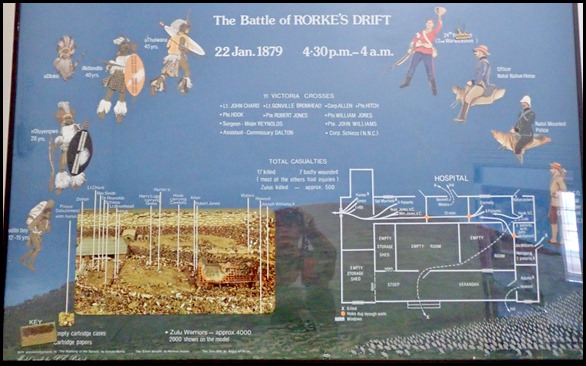

against.

Above the model, an overview.

In the final room a display of excavations of the

site.

Relief. The patrol’s emotional

return to Rorke’s Drift. The colour was received by Colonel

Glyn, commanding the 1/24th.

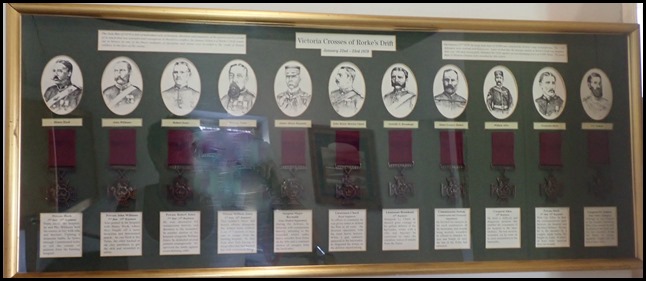

Victoria

Crosses of Rorke’s Drift – January 22nd and 23rd 1879. The writing

top left. The Zulu War of 1879 is full of individual acts of heroism,

devotion and situations of the gravest peril: yet out of so much that was

splendid and courageous in that fierce conflict. the famous Defence of Rorke’s

Drift stands out in history as one of the finest examples of discipline and

valour ever recorded to the credit of British soldiers in the face of the enemy.

The writing top right. On January 22nd 1879, the main Zulu Impi of

20,000 men attacked the British Camp at Isandlwana. The 1,500 defenders were

overrun and massacred. Later on that day, the mission station at Rorke’s Drift

was attacked. Just over 100 men successfully defended Rorke’s Drift against an

overwhelming force of 4,000 Zulus. No fewer than 11 Victoria Crosses were

awarded for this action.

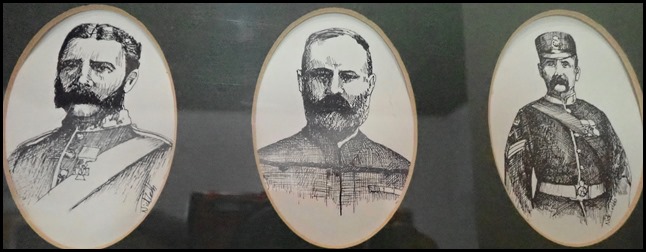

The writing below each soldier:

Private Henry Hook 2nd Batt. 24th Regiment. From

inside the hospital, he and Pte. Williams held the enemy at bay with rifle and

bayonet. Fighting a desperate battle, he broke through 3 partitioned walls to

aid the escape of patients from the burning hospital. Private John Williams 2nd Batt. 24th Regiment. Also posted

in the hospital with Henry Hook, where they fought off a most ferocious and

determined attack. As one fired at the Zulus, the other hacked at the clay

partitions to get the sick and wounded to safety. Private

Robert Jones 2nd Batt. 24th Regiment. He was decorated for conspicuous

bravery and devotion to the wounded. In another section of the hospital

alongside William Jones, he defended several patients courageously. He survived

the battle against overwhelming odds.

Private

William Jones 2nd Batt. 24th Regiment. This soldier’s brave and heroic

efforts alongside Pte. Robert Jones enabled 6 out of 7 patients in their care to

escape from the burning hospital. He shot Zulu after Zulu having to swap rifles

that had burned hot with continuous firing. Surgeon Major

Henry Reynolds Army Medical Department. During the defence, he behaved

with conspicuous bravery, attending to the wounded whilst under heavy crossfire

from Zulus on the hills and a continual shower of assegais from the barricades.

Lieutenant John Rouse Merriot Chard Royal Engineers.

As officer in command, he was given orders to defend the Post at all costs. He

directed operations with the most heroic bravery. When a gap suddenly appeared

in the barricade he dispensed troops so the defence stayed

strong.

Lieutenant

Gonville S. Bromhead 24th Regiment. Alongside Lt. Chard, he showed great

courage in his gallant defence of the barricades, where with a rifle and bayonet

he continued to repel the relentless wave of attacks from the Zulus. Commissariat James Langley Dalton Commissariat and

Transport Department. He devoted his energies to the swift construction of the

barricades, and despite being severely wounded, he refused to abandon his post

and fought on until the last of the Zulus had retreated. Corporal William Allen 24th Regiment. He held a difficult

and dangerous position that enabled the evacuation of the hospital to the Inner

Defence. He was severely wounded, yet he went on to carry ammunition to the

barricades.

Private

Frederick Hitch 2nd Batt. 24th Regiment. With Cpl. Allen, he kept the

communications open between the hospital and the Inner Defence. He was hit in

the shoulder by a roughly made bullet, but fought on. Later, 36 pieces of bone

were removed from his wound. Corporal Ferdinand C.

Schiess Natal Native Contingent. Although he was a patient in the

hospital recovering from a leg wound, he took his place at the front wall. On

one occasion during the battle he single-handedly fought off and killed three

Zulus.

So why have I written out so much in the two blogs about Rorke’s Drift. Primarily because it is fascinating and such a well known battle but also because it means so much to Bear. Also Roger (Mark our son-in-law’s dad) has a print of a battle painting in the hall, and we bought one for my brother, Pete. They all loved the bravery shown at Rorke’s Drift. One day I’m sure I will buy a print for Bear.

ALL IN ALL SO PLEASED TO SEE BEAR TICK OFF THIS WISH A LIFETIME DREAM COME TRUE |