Tullah

Beez Neez now Chy Whella

Big Bear and Pepe Millard

Tue 26 Jan 2016 23:47

|

Tullah, Farrell Mine, Trains and a Dam

We had an

enjoyable time with Lyn, her bears and her blooms.

On the opposite side of the road was

an intriguing structure, a

poppet, so over we went.

The township in

1905. St Andrew’s Church erected by volunteer

labour and opened in 1913. Tullah Hotel before it was

destroyed by fire in the 1930’s

The Town of Tullah: Many towns that

once existed on the West Coast have long disappeared back into the

forest,Magnet, Dundas, Williamsford and even recent settlements such as Luina,

Australia’s second largest tin mine in the 1960’s and 1970’s can now barely be

seen under a generation of forest regrowth. Although the settlement on the

slopes of Mt Farrell faltered in the depression years of the 1930’s and the mine

closed long ago, Tullah has survived.

Initially it was called Farrell,

after Tom Farrell. When the settlement was declared a township in 1901 it was

named Tullah, an Aboriginal word meaning ‘meeting of the waters’. Before the

hydro-electric schemes were built in the 1980’s, the township was near the

confluence of the Mackintosh and Murchison Rivers.

In 1908 the town was well established

with four hundred and seventeen people living in two ‘suburbs’ sharing two

hotels, two general stores, a cottage hospital, state school, post office, bank

and a public hall with the rather grand title of the Tullah Academy of Music.

With little competing for entertainment, Elsie Tole organised concerts there as

well as teaching music lessons.

The town had its own football and

cricket teams, brass band and like almost every other West Coast town, a homing

pigeon racing team.

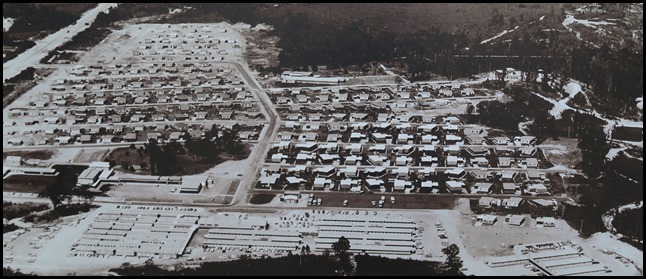

1982. That same year the state Hydro

Electric Commission [now Hydro Tasmania] began construction on the Pieman River

Power Development. Tullah’s population skyrocketed. By 1980 Tullah village had

more than two hundred and sixty houses, with separate accomodation for nearly a

thousand workers. The population soared to nearly two thousand.

When the Pieman River scheme was

completed in 1987, the town remained the base for the new King and Anthony

schemes. When these schemes were completed in 1994 Tullah

Village was put on the market. A house could be bought for as little as

ten thousand dollars. many were sold to redundant HEC workers or to anglers keen

to pick up a weekender, but the majority were bought by miners from the nearby

Hellyer or Henty mines.

The last chapter on Tullah has yet to

be written.

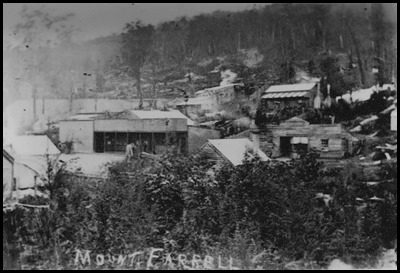

The Mines of Tullah: Circa 1904, an

early view of South Tullah looking at south Mount Murchison. Circa 1905, well established, the Mount Farrell Mining

Field was to be known as Tullah. The

settlement of Tullah, once a cameo frontier mining town which in the mid

1970’s became part of a major hydro-electric development.

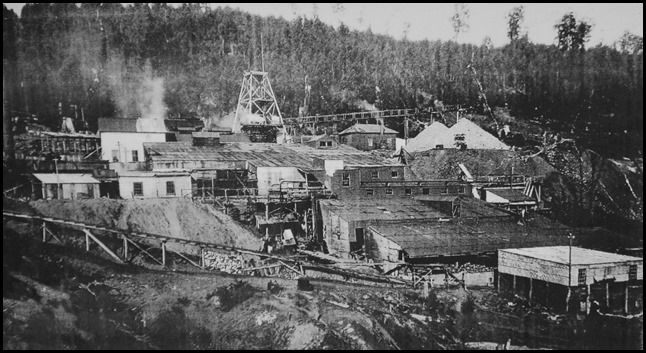

North Mt Farrell

mine workings looking south-easterly circa 1920.

Mount Farrell is

named after prospector Tom Farrell who discovered galena on its eastern slope in

1892. While he had some success mining copper, the lode was patchy and

unprofitable. Two years later he moved on.

Payable lodes at

Mount Farrell were found however, when the Innes brothers were surveying and

cutting the track from Liena near Mole Creek to the new mining fields at

Rosebery. The brothers did not publicise their find, but returned ten months

later to peg their their claim. In 1899 the North Mt Farrell Co. was formed and

very quickly consignments of ore were packed out by horses to the Emu Bay

Railway Line.

By 1906, the mine had

produced more than 430,000 ounces of silver and 4,000 tons of lead, and a

township was established.

The mine prospered and the community grew, but by the 1930’s the quality

of the ore had diminished. As the Great Depression took hold, metal prices fell

and for the fifty miners and their families the outlook was bleak. The mine

closed. Milling operations continued but only a few days before the scheduled

closure another, richer outcrop of galena was found just north of the old

mine.

The North Farrell Mine re-opened in 1934, producing 700,000 tonnes of

silver-lead ore by the time it closed in 1974.

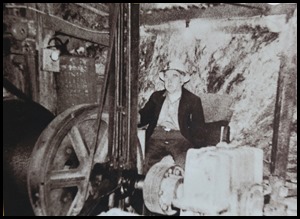

The winch

mechanism in this shed was used at both North Mt Farrell mines. It was

originally powered by steam and later by electric motor.

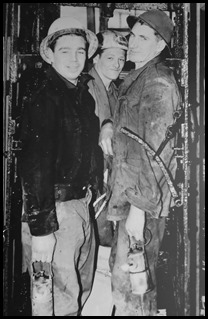

The winch driver, Rollie Anderson at the controls of the auxiliary

underground winder used to facilitate mine development. Going down. Miners Tony

Tyler, Kevin Roles and Sid Brookes in the cage of the

Farrell mine in 1962. At 1,000 feet [304 metres] the mine at that time was the

deepest on the West Coast. Some of the veterans of the

mine a few years before its takeover by the EZ Co. in 1964. From left:

Leo Powell, Alf Richardson, Bert Richardson and Mick Mahoney.

The cage

and the ore trucks under the poppet head are

originals that were used at the new North Mt Farrell shaft.

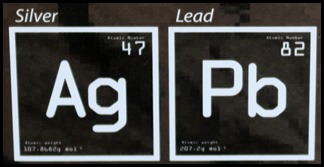

All that glistens is not gold.

Although mostly humble lead, Galena can be a

beautiful mineral. Some galena crystals have been discovered as large as twenty

five centimetres across. The lustre is from the silver, the metal still most

prized for its unique reflective quality. The ore

mined at Mt Farrell was galena, commonly called silver lead, or more accurately,

lead sulphide. Galena [Latin for silver lead] is the most common form of lead

bearing ore around the world. At its height, the Farrell mine produced galena

that was 63% lead and 60 ounces of silver t the ton. Prior to both world wars,

there was an enormous demand for lead for bullets and before its toxic effects

became better understood it was commonly used as a performance booster in

petrol.

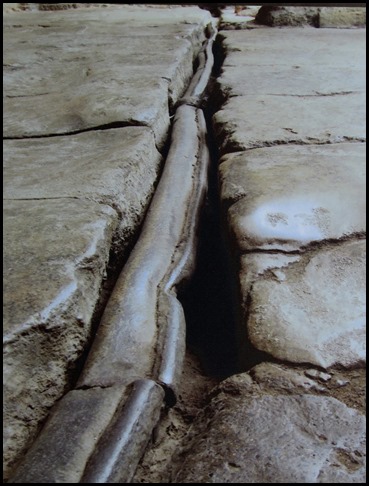

Two thousand year old Roman lead pipes unearthed in Bath, England.

Because it does not corrode, melts at

low temperatures and is easily beaten into any shape, the Romans used lead

extensively for plumbing [from the Latin plumbum, for lead]. Although now

treated warily, it still has many uses, notably fishing sinkers and, perhaps

more importantly, protective aprons to prevent excessive x-ray radiation to

medical staff and patients.

In Roman times it was widely accepted

that lead added an ‘agreeable flavour’ to many

dishes, despite suspicions that there was a connection between mysterious

maladies and the metal. The metal enhanced one-fifth of the four hundred and

fifty recipes in the Roman Apician Cookbook, a collection of recipes.

Some historians believe this practice may have contributed to the fall of

Rome.

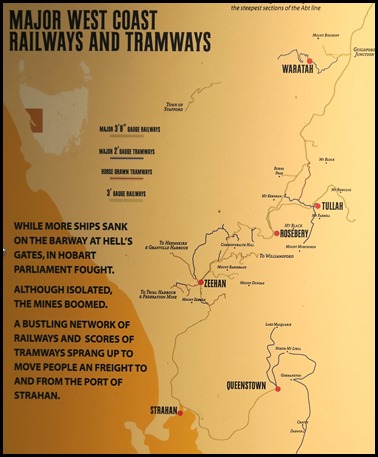

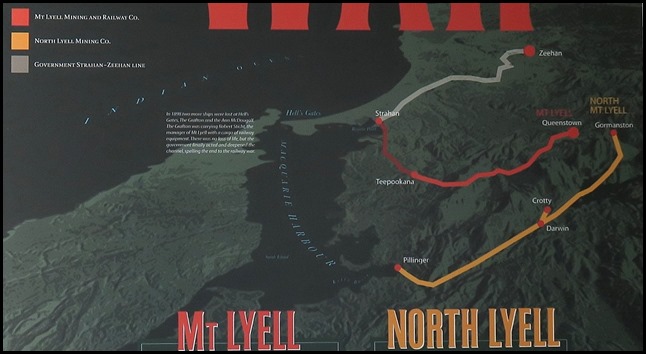

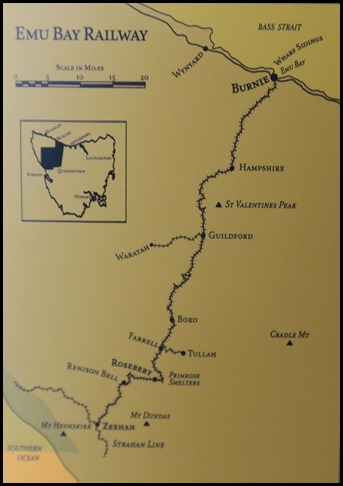

The Railway Links to Tullah: The only

access to all the mining fields on the West Coast was by crossing a long sand

bar that protected the narrow entrance to Macquarie Harbour. At low tide the

sand bar was only nine feet below water and at high tide only two feet

deeper.

Inside the bar was a channel less

than a hundred yards across and fourteen fathoms deep where a furious tidal ebb

and flow raced in and out of the harbour. Shipwrecks were frequent. Ships often waited, riding the southern

ocean swells for ten or twelve hours before venturing across the bar. Sometimes

they would have to sail south to Port Davey to wait for better

conditions.

In the 1890’s, seven ships were lost

in five years.

Insurance and freight charges for the

trip to Burnie to Strahan were six times more expensive than from Burnie to

Sydney. The largest ships that could clear the bar were limited to six hundred

tons at a time when steamers were being built many thousands of tons

larger.

In 1896 the government engaged a

leading British maritime engineer, Napier Bell, who recommended deepening the

channel. However, for many state politicians, Hell’s

Gates was a ‘sacred’ barrier against the ships of Melbourne: reason for

inaction. “The removal of Macquarie Harbour bar would be one of the rashest

undertakings that could be proposed by any man that has the interests of

Tasmania at heart. It would be throwing trade into the hands of Victoria.”

Hon C.D. Hoggins MHA .

Between 1886 and 1889 the ‘budding

city’ of Teepookana on the King River was serviced by

thirteen barges ferrying coal, coke, timber, beef and stores to be loaded onto

the Abt trains bound for Queenstown and smelted copper to Strahan on their

return. Two engines working in tandem on the steepest

sections of the Abt line.

Regatta

Point, Strahan exported more wealth than any other port in Tasmania

1900-1901.

Queenstown

Station 1902. Dub No 6 at Guildford Junction,

circa 1902

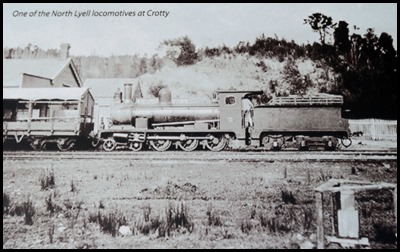

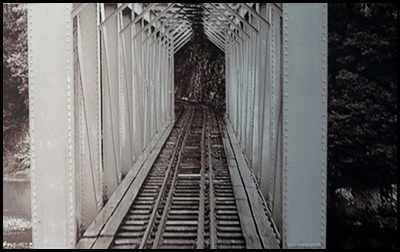

The region became home to a huge

assortment of trains and trams – a train spotters delight. They ranged from the

Abt locos that ran on a rack and pinion track to the impressive 86’ locomotives

that ran on the North Lyell line from Gormanston to Kelly Basin. They included

Tullah’s ‘Wee Georgie Wood’. Other lines were notable for introductions of new

technology – such as the Garrets with articulated axles that plied the notorious

“ Serpentine” North-East Dundas Line.

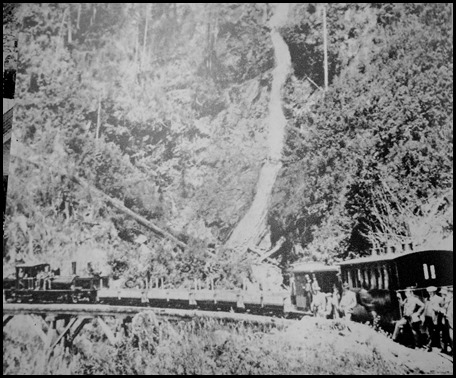

The west coast also became a

destination for adventurous tourists, looking to see for themselves exotic

sounding places such as Montezuma Falls [named after

the Aztec emperor who lost his gold and his empire to the Spanish

Conquistadors]. Travellers to the Falls were sprayed with mist from three

hundred feet above. To get a good view of the top they would lie across the

carriage seats on their backs craning their necks to look up.

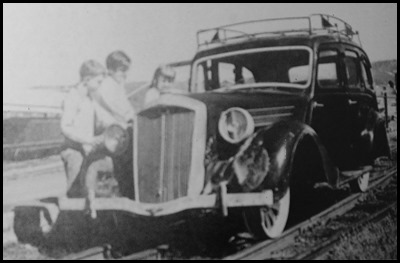

With petrol motors, railcars became

common for emergencies or the well-to-do. This 1947

Wolseley belonged to the manager of the EZ Co. mine at Rosebery and was

used on the Rosebery-Burnie line until 1964.

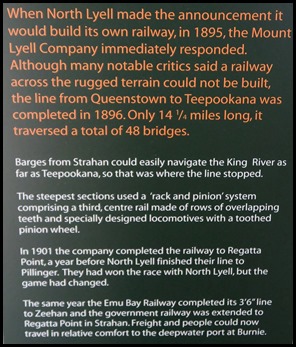

The Railway War: In 1883, near where

Queenstown stands today, prospectors found gold at the ‘iron blow’. As well as

gold, there was a vast lode of copper. The discovery was to become one of the

richest mines in Australia’s history. The ensuing boom sparked an intense

railway war as competing syndicates from around the state lobbied the government

into building a railway from Hobart, Launceston and Burnie to the peaks of

Lyell.

As long as sand clogged the entrance

to Macquarie Harbour, any of the deepwater ports around the State could compete

for the West Coast trade. In the late 1890’s, eight competing syndicates had

formed to establish a rail route to the riches in the west. All of them

petitioned parliament, appeared before select committees and sent surveyors and

axemen into the wilderness. They also fought each other with propaganda, in the

local press, public halls and especially in the English newspapers. Most of them

denigrating the opposition while exaggerating the extraordinary benefits of

their own schemes.

The Hobart - Launceston Feud: Then as now there was

intense competition between Hobart and Launceston. A Launceston syndicate had

funded the enormously rich tin mine at Mt Bischoff. In 1875 smelters were

established on the banks of the South Esk River, and the northern city embarked

on a period of great prosperity. This seeming advantage had provoked two rival

syndicates in Hobart to act, one of them even suggesting the unproven technology

of an electric railway that would run from the southern city to the western

mining fields. Both proposals, however were publically ridiculed. Through the

rugged terrain, rail routes could not be found from either Launceston or

Hobart.

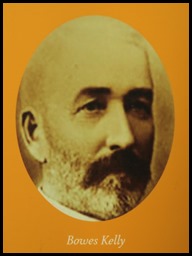

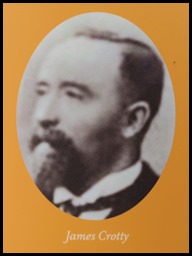

The Feud of the Irishmen: There was a

personal element to the war between the two Lyell mining companies. James Crotty

had been one of the original prospectors of ‘Iron Blow’ but the mine had

struggled until Bowes Kelly, one of Australia’s

wealthiest men after his investment in the Broken Hill silver mine, bought into

the Mt Lyell Mining Company. Later, when the company sought to raise finance for

its railway using London money rather than call on local shareholders, James Crotty found himself no longer on the Board of

Directors.

Crotty held Kelly responsible.

however, Crotty had retained the North Lyell mine and when it was discovered to

be far richer in copper than the ‘Iron Blow’ at Mt Lyell, it became Crotty’s

personal goal to wrest back control of Mt Lyell from Bowes Kelly.

It was not to be. After Crotty

suddenly died in 1898, copper prices plummeted and in 1903 the two companies

merged. The township of Crotty and Darwin disappeared as quickly as they had

sprung into existence, while Bowes Kelly remained on the new company board,

still in control.

The EBR

prospectus published in national and British newspapers showed the EBR line as the only railway in the region. The version

published in Tasmania showed the competing railways.......

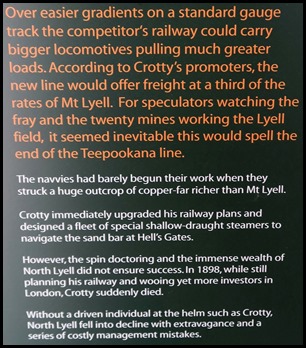

Greed, Gold Diggers and the Gullible:

In the atmosphere of a boom that lasted nearly two decades, speculation and

skulduggery were general practice. News of rich finds would create frenzies in

the Hobart and Launceston stock exchanges but all too frequently the mineral

samples that provoked such speculation were ‘salted’: samples underhandedly

taken from other mines that were of proven quality. On many occasions,

speculators were swindled. One of the most famous was the prospectus for the Emu

Bay Railway that showed only one railway [theirs] steaming into the Mt Lyell

fields.

Although a blatant lie, gullible

investors around Australia and in Britain subscribed four hundred thousand

pounds in a matter of days in one of the most hectic share rushes of the decade.

The directors, one of whom was Bowes Kelly, who also sat on the Mt Lyell board,

retained shares to the value of one hundred and fifty thousand pounds, rejected

applications for the other two hundred and fifty thousand shares and began

construction.

The dishonest publicity provoked

outcry, and when the Premier admitted in parliament he had privately given the

Emu Bay Railway the go ahead, his government almost fell. The scandal continued

to escalate when the shareholders were then told the railway would only go to

Zeehan, not to Queenstown. When Bowes Kelly was confronted, he calmly replied he

did not know about the misleading map.

We next went up

the hill in search of the dam and a place to picnic lunch.

The Mackintosh

Dam. A rockfill face dam about seventy five metres high and a crest

length of eight hundred and seventy seven metres, containing some nine hundred

and forty thousand cubic metres of material on the Mackintosh River and

Tullabardine Dam – a subsidiary rockfill concrete faced dam twenty five metres

high with a crest length of two hundred and fourteen metres and some one hundred

and eighty six thousand cubic metres of material containing Lake Mackintosh,

with twenty nine square kilometres of area, two hundred and twenty five metres

above sea level.

We read the

information board and had our picnic ‘in the bottom left hand corner’,

next to the access road. The Murchison Dam on the Murchison River is a rockfill concrete face

containing nine hundred and sixteen thousand cubic metres of material. Ninety

five metres high and a crest length of two hundred and twenty eight metres, two

hundred and forty metres above sea level. The two thousand metre Sophia Tunnel

diverts the flow of water from the Murchison to the Mackintosh catchment. The

rise and fall of Lake Murchison will be within ten metres, while the level of

lake Murchison will vary according to rainfall. Now, time to get back on the

road to Strahan.

ALL IN ALL AMAZING WHAT YOU

FIND ALONG THE WAY

INCREDIBLY DETAILED

HISTORIES |