Death Railway Museum

Beez Neez now Chy Whella

Big Bear and Pepe Millard

Sat 9 Dec 2017 22:57

|

Death Railway Museum, Thanbyuzayat   After our emotional visit to the War

Graves our driver dropped us outside the gates of the

Death Railway Museum. Criticised by many on various

forums, we came with an open mind. Certainly impressed so far.

As we walked up the path, a very powerful

glass panel with the words One Life, One

Sleeper, beyond stood four emaciated railway

workers, frozen forever in toil.

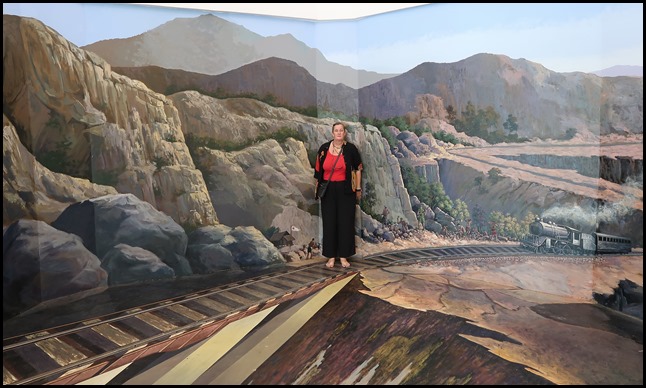

We walk in to find a massive wall and floor painting of the railway. Above right is a

television screen showing a film made by a brother and sister who walk the line

(or what’s left of it) in Thailand, a mammoth task in the heat, with few

directions but they meet loads of nice people along the way. Very

moving.

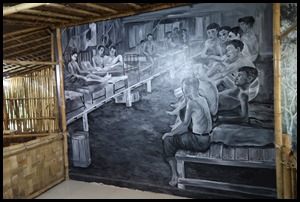

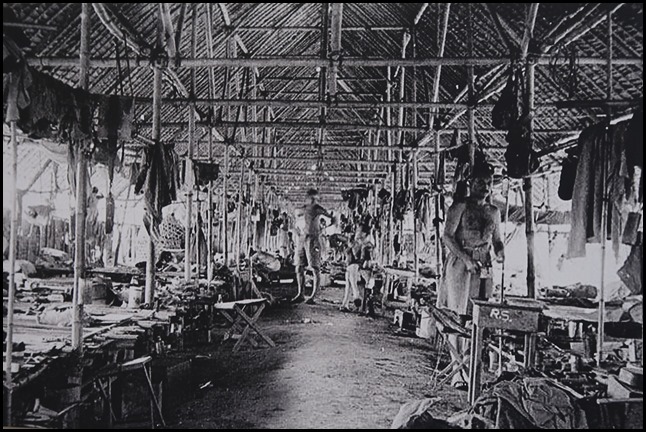

The next room is set

out like barracks with wall paintings.

Along the back wall was a wall painting showing the railway and the air con units

were part of the painting. Further round from the emaciated soldiers was a

diorama depicting a Japanese officer and his

subordinate.

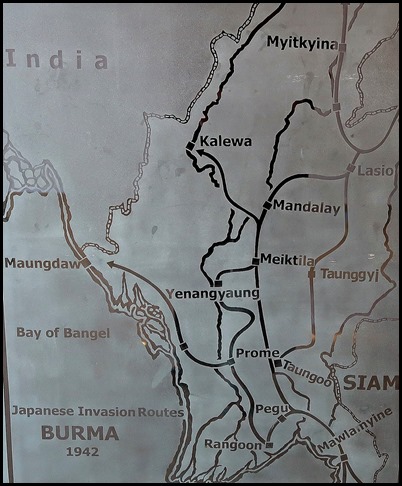

A glass information panel showed this map

and read: The Japanese Expansion

What was the ‘Greater East Asia

Co-Prosperity Sphere’ ?

This included countries such as

Australia, New Zealand, Malaysia, Burma (Myanmar), Thailand, French Indochina,

The Dutch East India.

Japan wanted these countries to be

part of its empire.

These countries held oil, tin and

rubber which were important resources for Japan to be

self-sufficient.

These countries would also serve as

markets for Japanese goods.

Japan used the term ‘Co-Prosperity’ to

get Asians to believe that all the countries in the sphere would benefit

economically through this arrangement.

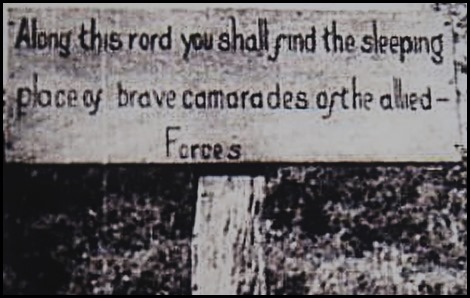

Upstairs, we

found many photographs of the time and behind them were two sets of glass

information boards that we have typed here – exactly as we saw them. The

mistakes do not detract from the message and are quite quaint in their own

way.

Constructing The

Railway

Purpose

There were four main purposes in

constructing the railway. They were:-

1. To transport ammunition in the

fight for the Greater Asia.

2. To transport Burma’s export and

import goods.

3. To build friendship with other

countries.

4. To make Burma

prosper.

To be able to accomplish the above

mention purpose, Workers Recruitments Group was formed and chaired by U Ba

Saw.

Planning

Surveyed by the British government of

Burma as early as 1885. In early 1942, Japanese forces invaded Burma. To supply

their forces in Burma, the Japanese depended upon the sea, bringing supplies and

troops to Burma through the Strait of Malacca and the Andaman Sea. This route

was vulnerable to be a tacked by Allied. To avoid it a railway from Bangkok to

Rangoon seemed a feasible alternative. The Japanese began the project in June

1942.

Constructing

After preliminary work of airfields

and infrastructure, construction of the railway began in Burma on 15 September

1942 and in Thailand in November. On 17 October 1943, construction gangs

originating in Burma met up with construction gangs originating in Thailand at

kilometer 263, about 18 km (11 mi) south of the Three Pagodas Pass. The

projected completed in December 1943.

Logistics

When the British left Burma in

1940-41, 2852 miles (4589 km) of rail-track were

left in Burma. Among those rail-track, Japan took 150 miles of track from

Yangon-Taungoo Duel Track and about 150 miles of track from Dadaroo-Myingyan and

other tracks.

Facts of the

Railway

The Death Railway was a 415-kilometre

(258 mi) railway between Ban Pong, Thailand, and Thanbyuzayat, Burma, built by

the Empire of Japan in 1943 to support its forces in the Burma campaign of World

War II. This railway completed the railroad between Bangkok, Thailand and

Rangoon, Burma (now Yangon). The line was closed in 1947.

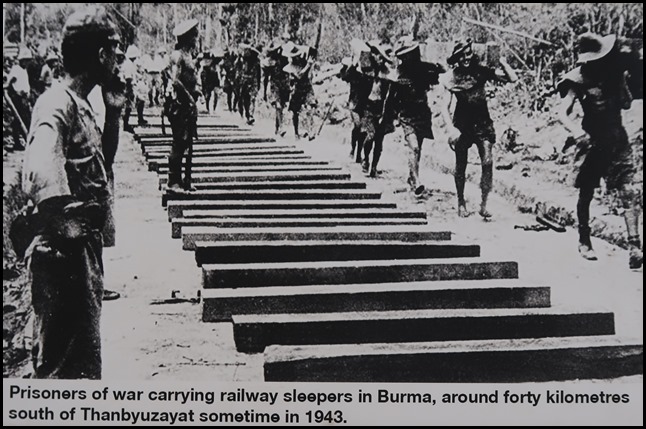

More than 180,000 – possibly many more

– Asian civilian labourers (Romusha) and 60,000 Allied prisoners of war (POWs)

worked on the railway.

Of these, estimates of Romusha deaths

are little more than guesses, but probably about 90,000 died. 12,621 Allied POWs

died during the construction. The dead POWs included 6,904 British personnel,

2,802 Australians, 2,782 Dutch, and 133 Americans. 69 miles (111 km) of the

railway were in Burma and the remaining 189 (304 km) were in

Thailand.

Invasion of Burma

(Myanmar)

The Japanese invasion was carried out

by General Shojiro Iida’s Fifteenth Army together with 30 comrades of Burma and

3,000 Mons who joined them at Bangkok. The main purpose was to cut the Burma

Road connecting to China. The invasion was followed by the signing of a treaty

of friendship on 14 December 1941 with Thailand. On the following day the first

Japanese troops entered Burma in the Kra Isthmus. The plan involved two main

thrusts. First the Southern Army would attack the southern tip of Burma to

occupy the British airfields, and then Gen. Iida would cross the border from

Reheng, and advance towards Rangoon. Japan would then be able to advance north

up the main Burmese river valleys.

The

Campaign

First

Phase

On 16 January 1942 a Japanese

battalion occupied Victoria Point (Kwak Thaung). Tavoy fell on 19 January. The

main Japanese invasion came from Raheng. They were blocked at Kawkareik.

Moulmein (Mawlamyine) fell on 31 January. The British retreat across the Sittang

on 19 February, and cross the river on the night of 21-22 February. On the

following morning two Japanese regiments attacked the bridgehead on the eastern

bank on the river. At 05:30 AM of 23 February, the bridge was blown. The British

pulled back to Pegu, half way to Rangoon. Pegu fell and a Japanese division was

closing in to the Yangon city on 5 March, sweeping around the city to the north

to attack from the west. The British realized that they couldn’t hold Rangoon,

and ordered an evacuation to leave along the road to Prome (Pyi), they ran into

a Japanese roadblock.

On 8 March, as the last British train

left Rangoon, the Japanese marched into the undefended city from the

west.

After the fall of Rangoon the fighting

died down. During the rest of March, both sides received reinforcements and

prepared for the second phase of the campaign – the inevitable Japanese attack

north into the heart of Burma.

Second

Phase

Serious fighting resumed in late

March. The Japanese advanced into the center, to Toungoo (30 March) and Mandalay

(1 May), and to the east, reaching Lashio (29 April), cutting the Burma Road. In

the west Japanese army advanced up the Irrawaddy against the British, forcing

them out of Prome (2 April) and Magwe (16 April). On 21 April, Alexander ordered

general retreat across the Irrawaddy, and on 26 April the British began their

long retreat back to the Indian border.

The British and Burmese lost 13,463

men during the campaign in Burma, while the Chinese may have lost as many as

40,000 men. Japanese losses were much lower, at 4,597 dead and wounded. The

battle in the air was a little more equal, with 116 aircrafts lost by the Allies

and a similar number by the Japanese.

Workers (POWs and The Sweat

Army) Myanmar.

At first, workers were collected from

the nearby area but later the construction team asked for help from the Interim

Government of Burma (Myanmar) in mid December in 1942.

The ministry of information announced

to form a Sweat Army to construct the railway on 18th December 1942. The

announcement described that 20,000 workers are needed and the salary,

accommodation, medication and other opportunities and also called to enter into

the Sweat Army.

Workers were collected from Taunggoo,

Innsein, Hinthada, Pathein, Dawei, Myeik, Mawlamyine, Thaton, and Pegu area. Up

until February 1943, totally 13,950 workers were collected. This was just a

little more than half of the targeted numbers and a lot of workers ran away. The

15th Japanese Army have to fine ways to get the needed workers because the

railway needed to be finished in time. The Japanese Army discussed with Railway

construction team military head and administration department to recruit

voluntary workers in 1st March 1943. The 15th Japanese Army ordered to set up

the workforce and to transport them on 2nd March.

More 30,000 workers were recruited

until 9 March 1943 to work in Myanmar-Thailand railway. The Burmese (Myanmar))

Army was Blood Army and therefore the workers were named Sweat Army. They were

later named “Bama Let Yon Tart” (Bama’s Strength Army). The Minister of

Transportation and Irrigation, acted as chair of recruitment committee,

appointed the District Administrators as leaders of recruitment team and

recruited workers through the help of Township Administrators and Village Heads.

“ Doh Bama Sinyethar Aseayon” (We Burman Poors Association) also helped to

recruit workers. Military Administration provided 210,000 Kyats as a recruitment

cost. 32,204 voluntary workers were recruited within a short time and

transported as the first group. But there were a lot of workers running

away.

Therefore the the 15th Army hasto

discuss with military administration to recruit 21,000 more. The first

recruitment were done in nine different districts and the second recruitment was

done in Kyaukse, Maoobin, Minbu, Pakakku and Thayet districts. The recruitment

leaders were also extended from 1000 per one leader to 100 par one leader. The

second recruitment brought in 18,615 workers. Because of workers were running

away the 15th Japanese Army again have to ask for help in July 1943 to recruit

20,000 more workers. This time was recruited from Shwebo, Kathar and Monywa

districts and 21,069 more workers were recruited this time. A Patriot Youth

Group called Heihi was set up in Burma’s Japanese Armies HQ. The New Light of

Myanmar newspaper describe on 20th April 1943 to enter into Heiho. This Heiho

Army played a central role recruiting workers.

Japanese

12,000 Japanese soldiers, including

800 Koreans were employed on the railroad as engineers, guards, and supervisors, about 1,000 (8 percent) of them

died during the construction.

Romusha

The first prisoners of war, 3,000

Australians, to go to Burma departed Changi Prison in Singapore on 14 May 1942

and journeyed by sea to neat Thanbyuzayat, the northern terminus of the railway.

They worked on airfields and other infrastructure initially before beginning

construction of the railway in October 1942. In early 1943, the Japanese

advertised for workers in Malaya, Singapore and the Dutch East Indies, promising

good wages, short contracts, and housing for families. When that failed to

attract sufficient workers, they resorted to more coercive methods, rounding up

workers and impressing them, especially in Malaya. Approximately 90,000 Burmese

and 75,000 Malayans worked on the railroad. Other nationalities and ethnic

groups working on the railway were Tamil, Chinese, Karen, Javanese and

Singaporean Chinese.

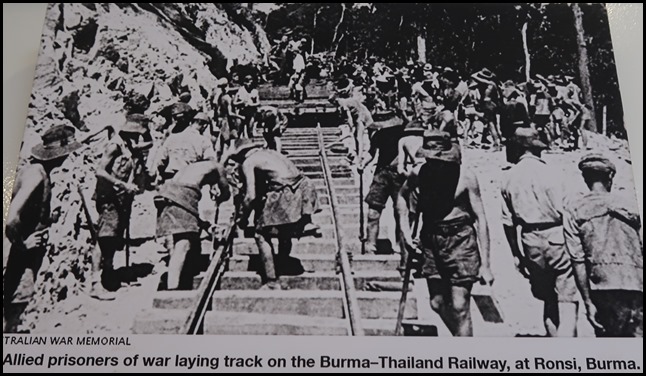

Prisoners of

War

The first prisoners of war, 3,000

Australian, to go to Burma departed Changi Prison at Singapore on the 14th May

1942 and journeyed by sea to near Thanbyuzayat, the northern terminus of the

railway. They worked on airfields and other infrastructure initially before

beginning construction of the railway in October 1942. The first prisoners of

war to work in Thailand, 3,000 British soldiers, left Changi by train in June

1942 to Ban Pong, the southern terminus of the railway. More prisoners of war

were imported from Singapore and the Dutch East Indies as construction

advanced.

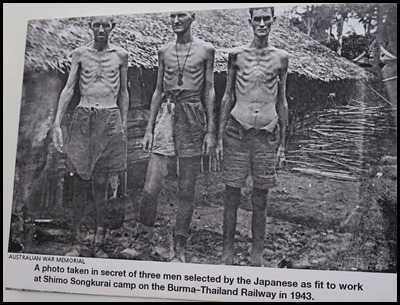

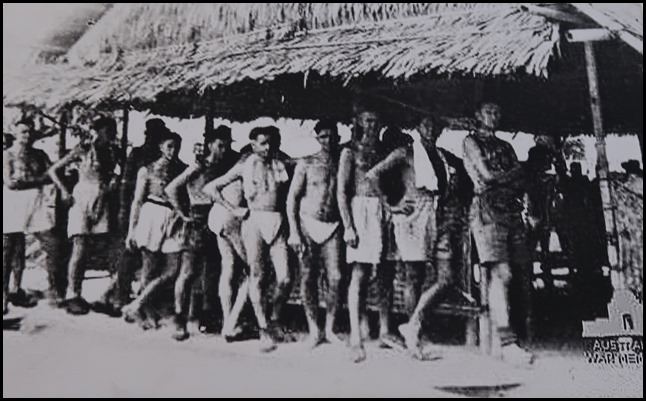

Conditions

The prisoners of war “found themselves

at the bottom of a social system that was harsh, punitive, fanatical and often

deadly. The living and working conditions on the Burma Railway were often

describes as “horrific”, with maltreatment, sickness, and

starvation.

Living

Construction camps housed at least

1,000 workers. Each was established every five to ten miles (8 to 187 km) of the

route. The construction camps consisted of open sided barracks built of bamboo

poles with thatched roofs. The barracks were about sixty metres (66 yards) long

with sleeping platforms raised above the ground on each side of an earthen

floor. Two hundred men were housed in each barracks, giving each man a two-foot

wide space in which to live and sleep. Camps were usually named after the

kilometre where they were located.

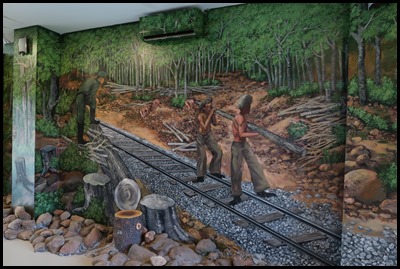

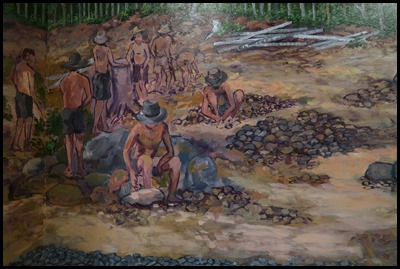

Working

Working conditions for the Romusha

were deadly. A British doctor said “the conditions in the coolie (Romusha) camps

downriver are terrible.....They are kept isolated from Japanese and British

camps. They have no latrines. Special British prisoner parties.....bury about

twenty coolies a day. These coolies have been brought under false pretence –

‘easy work, good pay, good houses!’ some have even brought wives and children.

Now they find themselves dumped in these charnel houses, driven and brutally

knocked about by the Jap and Korean guards, unable to buy extra food,

bewildered, sick, frightened. Yet many of them have shown extraordinary kindness

to sick British prisoners passing down the river, giving them sugar and helping

them into the railway trucks. The workers were moved up and down the railroad

according to the need of the construction. Moreover, the road was constructed

only with basic tools without any machine”.

Health

In his book, Last Man Out, H. Robert

Charles, an American Marine survivor of the sinking of the USS Houston, writes

in depth about a Dutch doctor, Henri Hekking, a fellow POW who probably save the

lives of many who worked on the “Death Railway”. In the forward to Charles’s

book James D. Hornfischer summarises: “Dr. Henri Hekking was a tower of

psychological and emotional strength, almost shamanic in his power to find and

improvise medicines from the wild prison of the jungle”. Hekking died in 1994.

Charles died in December 2009.

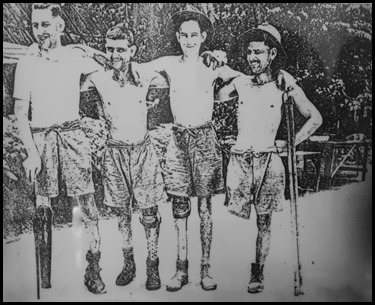

Entertainment

One of the ways the Allied POWs kept

their spirits up was to ask one of the musicians in their midst to play his

guitar or accordion, or lead them in a group sing along, or request their camp

comedians to tell some jokes or put on a skit.

. . Outside, we walked to the end of the

of the track which now looks very benign. Just a few feet in front of it

is the main line.

We walked back along the track to the perimeter gate,

passing a pile of bent and battered rails (originals)........

........stopping by two statues of Japanese soldiers to stand beside C.O.522.

Heading back inside passing the outdoor wall

paintings.

Pictures of sad.

remnants

ALL IN ALL VERY WELL PUT TOGETHER

BEAUTIFULLY

PRESENTED |