IAMM Bits & Bobs

|

IAMM Bits & Bobs that

Caught Our Eye

Such a massive collection cannot be

given justice in a blog, so here are some bits and bobs that, for us, stood out.

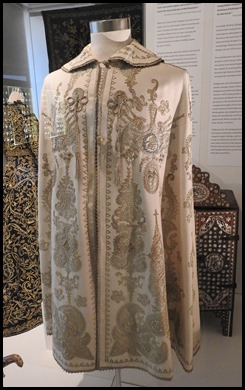

Embroidered Velvet Robe. Turkey. 19th century. Crib and beautiful wall unit. Circa 1900. Embroidered Wool Cape. Ottoman Empire. Circa 1900.

Palace bridal

suite.

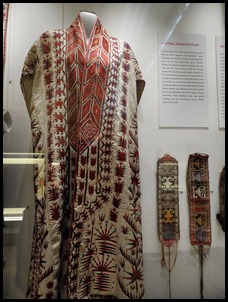

Silk Lampas Robe.

Sogdiana, Central Asia. 7th – 8th century

AD.

Located at the heart of the Asian

landmass, Central Asia has both separated and connected great civilisations for

hundreds of years. Flourishing trade gave rise to urban settlements, which

reached heights of cultural development between the mid 14th and late 16th

centuries, under the Timurid Empire. The Timurids brought skilled craftsmen to

cities like Bukhara, Samarkand and Herat, and encouraged the production of

exquisite textiles under craft guilds. The rural communities of Central Asia

equally excelled in textile arts. Tribes like the Uzbek, Khirgiz, Kazakh and

Turkoman have long expressed their proud equestrian and warrior legacy through

embroidery. Their hangings, bags, rugs, animal

trappings and tent decorations feature distinct colours and motifs.

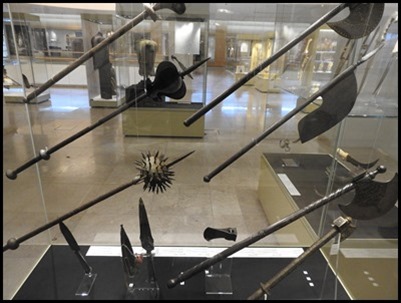

We bimbled around

the lethal weapons and bows.

Lacquered

Papier-mache fan. Qajar, Iran. 1883 – 1884 AD (one of my

favourite items).

Chess Board and

Complete Set of 32 Carved Ivory Chess Pieces. India. 19th century. The

earliest references to chess are found in Persian writings from around the 6th

century AD, which use the term chatrang. The term derives from the

Sanskrit chaturanga, meaning ‘in four parts’, and refers to the four

components of an early Indian army: infantry, cavalry, elephants and chariots.

The game is believed to have travelled across the globe following the Silk Road

and become vastly popular all over the world.

It is said that the Caliph Harun

al-Rashid carried on a chess match he was unable to finish, through

correspondence with his rival ruler, the Byzantine Emperor Nicephorus at the

turn of the 8th century AD. And in the 12th century AD, a book entitled

‘Book of Chess: Extracts from the Works of al-Adli, as-Suli’ was

compiled quoting Abbasid chess masters, al-Lajlaj and al-Suli, from the 10th

century AD.

In 1509 Diego Lopez, commander of the

first Portuguese expedition to Malacca, was recorded to be playing chess, when a

Javan from the mainland came aboard, immediately recognised the game and the two

men discussed the form of the pieces used in the chess set played

there.

Babur, the founder of the Mughal

Empire in his memoirs, characterised one of his nobles as “madly fond of chess”.

In his new capital city of Fatehpur Sikri, Babur’s grandson Akbar built a

life-sized chessboard in a courtyard and – using dancing girls and courtiers as

pieces – played from the apartments above.

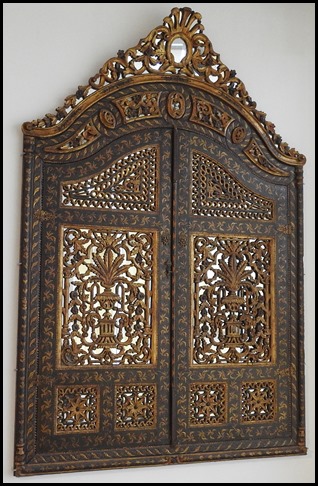

Carved wooden

window frame. Possibly Syria or Turkey. 19th century AD. Hispano-Moresque lustre vase. Spain. 19th century

AD

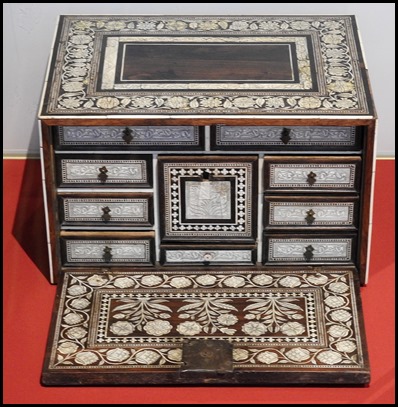

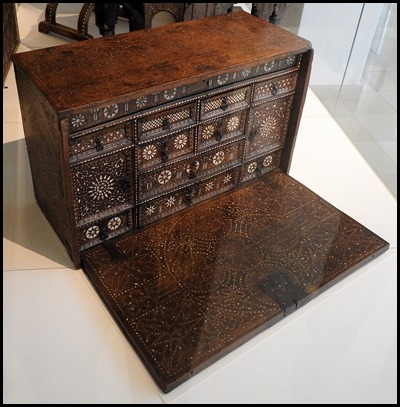

Ivory-inlaid wood

chest. India. 17th – 18th century AD. Walnut table

cabinet. Spain. 16th century AD.

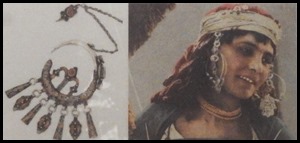

Sumptuous

jewellery.

Necklace –

Khanti / Rantai Leher – Khanti. Enamelled gold set with diamonds. North India.

circa 1850 – 1875 AD.

In Indian royal context jewellery is

worn as both adornment and _expression_ of wealth and power. Epitomising the

Mughal aesthetic for luxury, the overall effect of this necklace is the symbol

of splendour and magnificence. Commissioned for a wealthy patron, each diamond

was cut and foil-backed so as to bring out its maximum brilliance.

The necklace is set with diamonds in

Kundan technique and polychrome luminous enamel decoration on the reverse.

Kundan jewellery has made a royal mark in India’s history. It started out in the

North, specifically in Rajasthan. Its southern counterpart was in Hyderabad. The

hanging pendant, in the form of a peacock, a symbol of beauty and grace, adds a

three-dimensional element to the design. The enamelling on the reverse is also

of the highest quality, each panel within the rosettes features painted floral

petals and leaves with finely combed details that add a sense of

palpability.

Gold

Tiara. Morocco. 1800 AD: A richly jeweled Moroccan wedding tiara. It is

decorated with emeralds and gemstones and displays a pyramidal shape facet and

open back. The gold jewellery of Morocco is often gifts associated with royalty

and noble ladies. It is inscribed with al-Izza Li’llah wa li-rasulihi

meaning honour belongs to God and His Messenger.

Pair of

Ceremonial Earrings. This sumptuous earrings, also known as

dewwah is most commonly found in the southern cities of Morocco

particularly in Marrakesh. The earrings are worn as part of a larger head gown

ornament. By attaching the chain onto the wearers’ head dress, the larger hoop

then loops around the front of the ear exposing the richly decorated adornment.

If they say so, to me anything but studs constitutes instruments of

torture......

Candlestick. Ottoman

Turkey. 1768. The calligraphic cartouches reads: Waqf for Jami’ Idris. The

generous patron Hajj Ali Agha Buyuk father of Abeh Mour and Haygun, present the

candlestands in the year 1181.

Candlesticks: Among the types of

lighting used in mosques were large candlesticks. They flanked the sides of the

mihrab niche and provided light to the structure during the early hours of dawn

and during evening prayers (Ishaa). According to

travellers like Al-Qazwini (died 1283 AD) and Ibn Battuta (died 1377 AD),

centres of production for metal candlesticks became popular in Northeast

Anatolia and in the province of Fars.

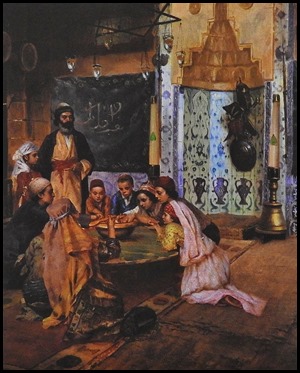

In the 15th century AD, Sultan

Bayazid II commissioned two large gilt brass candlesticks for his mosque complex

in Edirne, Turkey. In the 16th century AD, Sultan Suleiman the Magnificent is

known to have bought two colossal candles from Hungary to be be placed on both

sides of the mihrab at the mosque of Aya Sofya (Hagia Sophia). Turkish painter

Osman Hamdi Bey (1842-1910) depicted candlesticks in his paintings. The

exemplify the varied use of candlesticks in Ottoman Turkey. Details of La Charite chez les derviches a

Scutari, Rudolf Ernst (Austrian, 1854-1943).

Pair of

Armchairs. Vizagapatam, India. First half 19th century AD. Veneer inlaid

with ivory and mother of pearl.

British power in India, in the 18th

century, introduced Indo-European furniture styles which was favoured not only

by Europeans but also Indian rulers and elite. European traders began exporting

Western prototypes to copy and it was soon discovered that the Indian craftsmen

were highly skilled. This skill coupled with an incredible imagination led to

the emergence of the independent Indo-European style. Vizagapatam, a port in the

north of the Eastern Coromandel Coast of India, was renowned from the late 17th

century for inlaying and veneering ivory, and soon became the centre of the

manufacture of ivory-veneered Anglo-Indian furniture. The armchairs are veneered

with ivory, engraved with flowers and leaves as well as mythical beasts and

birds. Featuring a central mirror framed with studded tortoiseshell above

various openwork rails, the back embellished with metal jewel-like cartouches.

The seat on fluted solid ivory front legs and swept forward back legs are

supported by engraved gilt brass and gold peacocks with mechanical springs that

make the wings flap when weight is applied to their backs. The association of

peacocks with thrones, however, goes back to Shah Jahan’s famous peacock throne

built in 1635. Glad to see these chairs in a museum but very pleased they cannot

be made anymore with tortoiseshell and ivory anymore.......

Bird-shaped

Container. Etawah, India. Circa 1882 AD. Ivory and horn parquetry, inlaid

with mother of pearl.

Geometric parquetry of mother of

pearl, ivory and horn executed during the second half of the 19th century in

Etawah, a small town in the state of Kotah, Uttar Pradesh. This type of work was

produced by two or three families belonging to the Khatri caste. Although items

or Etawah were mentioned in the exhibition catalogues of Calcutta in 1882 – 1883

and the colonial and India exhibition in London in 1886, this is the only

bird-shaped container known. The featured artefact, the bird of prey, is covered

in geometric shapes of ivory and horn with details picked out in mother of

pearl. The hinged top with locking mechanism opens to reveal one single

compartment, originally lined in metal. The bird is supported on metal legs, its

claws clutched around its prey in low relief as an integral part of the stepped

base.

Canton famille

rose dish of Zill aI-Sultan. China. 1879 – 1880 AD.

Chinese Porcelain Exports for Qajar Royalties: Blue

Canton, Fitzhugh and other Chinese enamelled porcelains were highly prized by

the Qajar royalties. During the reign of Nasir al-Din Shah and his eldest son,

Zill al-Sultan, Chinese porcelains with the Qajar Coat of Arms; the lion, the

sun and the Kiani crown were commissioned for the royal court and as gifts from

the Shah.

Gold-inlaid Jade

Saucer. India. Circa 1900 AD and my favourite piece of jade.

Celadon Jade Dish. Mughal, North India. 17th – 18th century

AD.

Stunning glass

collection

Islamic Glass

Development: “He set before us whatever is sweet in the mouth or fair

to the eye. He brought forth a vase, which was as though it had been congealed

of air, or condensed of sunbeam motes, or moulded of the light of the open plain

or peeled from the white pearl”. Al Hariri (1054 – 1122 AD). An excerpt from the

12th century manuscript, the Maqamat. The translucent delicacy of glass

has long made it an object of desire around the world. The earliest examples of

glass were in the form of beads dated to around 2500 BC. Tablets written in

cuneiform about glass manufacture around 1300 – 1100 BC provide evidence of the

documentation and long history of glass production.

The production and decorative

techniques of glass in the Islamic world owe a debt to its predecessors: the

Byzantine empire within Syria and Egypt, and the Sassanian empire within Iraq

and Persia.

The history of Islamic glass may generally be divided into three periods. The 8th to the 11th Century: The development of glass-cutting techniques and revival of lustre painting on glass. As both Persia and Mesopotamia had thriving industries in the pre-Islamic period, after the advent of Islam this continued uninterrupted throughout Umayyad and Abbasid lands. The 12th to the 15th Century: The development of gilding and enamelling techniques in glassware. During this period, Syria and Egypt held a monopoly on glass production, though Iran and Iraq also contributed to a lesser scale. Islamic glass was highly regarded and widely distributed in the treasuries of Europe and as far afield as China. The 16th to the 19th century: The gradual decline of the glass industry and increasing adoption of Western influences.

ALL IN ALL AN

EXQUISITE COLLECTION

REMARKABLE FOR THEIR

AGES

|