IAMM Prayer Books

Beez Neez now Chy Whella

Big Bear and Pepe Millard

Sat 31 Dec 2016 23:27

|

Islamic Arts Museum Malaysia - Prayer

Books

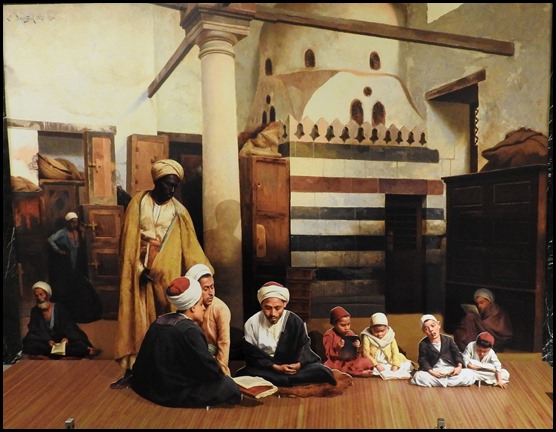

We entered the first special gallery

– a beautiful, big space, all marble and cool, a

welcome break from the days heat. Housed here is a temporary collection of the

illuminated prayer manuscripts of Dala’il al-Khayrat. We are here to learn what

we can about what we feel in many ways ignorant of and feel this is a good place

to start.

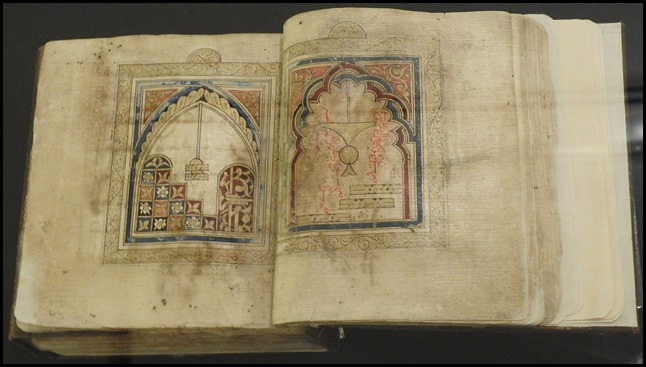

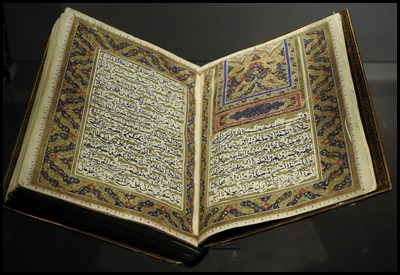

Morocco. 16th century AD / 10th

century AH. This manuscript is the oldest Dala’il al-Khayrat

copy in the IAMM collection.

Introduction:

This exhibition and its accompanying catalogue feature remarkable

illuminated prayer manuscripts of Dala’il al-Khayrat from

the collection of the Islamic Arts Museum Malaysia. Dala’il al-Khayrat reflect the spontaneous composition of salawat,

the blessings and praise upon the Prophet, composed directly from the heart of a

prominent Sufi master, Imam Al-Jazuli (died 1465). The composition has become an

important prayer book in its native land, Morocco, which has also spread across

the breadth of the Islamic lands. Today, Dala’il

al-Khayrat is celebrated as the most acclaimed source on the salawat upon the

Prophet Mohammad.

Dala’il al-Khayrat has for centuries inspired

calligraphers, illuminators and painters of court ateliers in producing

sumptuous prayer manuscripts, which reflect the distinctive designs of various

Islamic dynasties. These manuscripts uncover the story behind the text

appreciation by patrons and calligraphers, and to bring to light the skills as

well as the techniques of the craftsmen.

The tradition of reciting the

salawat of Dala’il al-Khayrat in public and private

gatherings continues until today, becoming the rationale behind this exhibition

in highlighting the significance of Dala’il

al-Khayrat and its impact on the lives of Muslims. The exhibition also seeks to

perpetuate the living practice of praising the

Prophet.

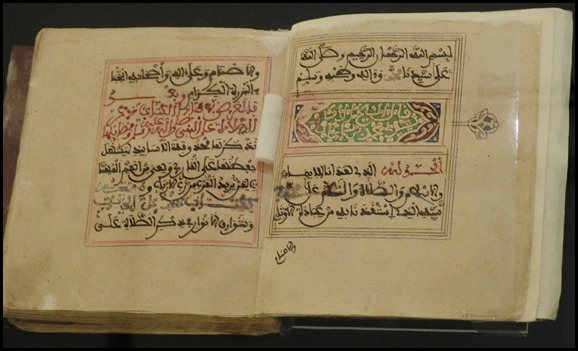

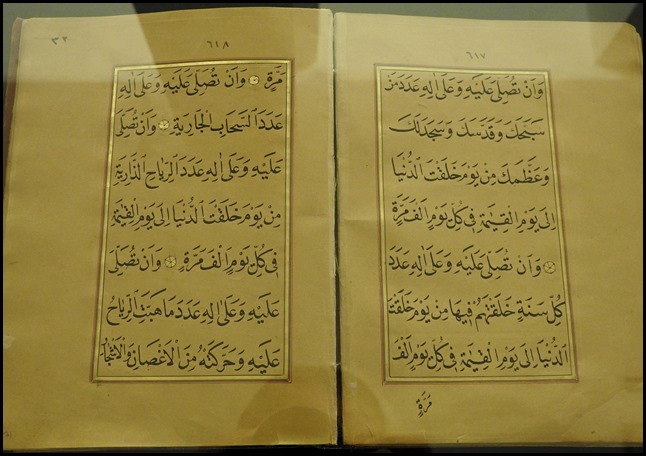

Dala’il

al-Khayrat, Morocco, 19th

century.

A Prayer Book: Dala’il al-Khayrat is a manual of salawat, blessings and

prayers to the Prophet Mohammad which was composed in Morocco during the 15th

century AD by a prominent Sufi of Shadhill school, Imam Al-Jazuli. Dala’il al-Khayrat is the most eminent and widely read prayer book

not only in its native land with the objective to assimilate the deep love

toward the Prophet Mohammad. It is considered as the most acclaimed source of

the salawat upon the Prophet Mohammad. The text were copied by many

scribes over the centuries – either produced in ateliers as a commissioned work

by a royal patronage or written down during the learning circles by disciples of

a Sufi

order.

After the time of Imam Al-Jazuli,

additional passages were also included. Some copies added Asma’ al-Husna, the

ninety nine names of Allah, and the names of twenty five prophets as mentioned

in the Qur’an. In some other copies, the instruction on the handling and

reciting the salawat is included at the beginning. The chains of

ijaza, certificate of reading or listening to the content of Dala’il al-Khayrat can also be found in several copies of this

work. As the prayer book has caught the heart of Muslims, many scholars of

Islamic thought have written an explanation or commentaries on it either

included in the margin of the copies of the Dala’il al-Khayrat or as a completely different work as a

whole.

Surah

Al-Ahzab: 56.

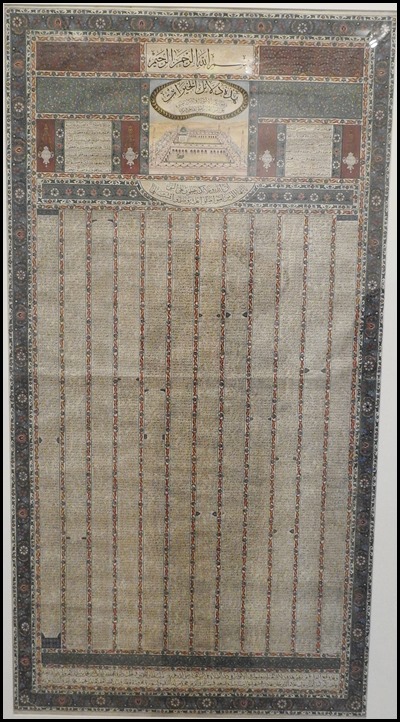

One-page Dala’il

al-Khayrat. Loharu, India. 1879.

About Imam al-Jazuli: Imam Abu

Abdullah Muhammad ibn Sulayman ibn Abu Bakr al-Jazuli al-Simlali al- Sharif

al-Hasani traced his ancestry to Imam Hassan ibn Ali, the grandson of the

Prophet Muhammad. He was a member of the Jazula Berber tribe, from a place

called Sus al-Aqsa, a town in southwest Morocco. His first nisba

(attributional name) refers to Jazula, his Berber tribe whereas his second

nisba refers to Simlala, one of the most important Berber tribes of

Jazula. He was living in Jazula where he began his quest for knowledge by

reading and memorising the Qur’an, and learning the traditional Islamic

knowledge from the scholars of his hometown.

He then travelled to Fez, and

attended lectures at Madrasah al-Saffarin where he mastered the Islamic

jurisdiction of the Maliki school and studied under the Sufi scholars of his

time such as Ahmad al-Zarruq al-Bamussi and Shaikh Abu Abdullah Muhammad ibn

Abdullah Amghar al- Saghir. From Fez, he travelled to various places including

Makkah, Madinah and Al-Quds, and stayed in these Holy lands of Muslims for

almost 40 years.

When he returned to Fez, Morocco was

facing the difficult times of political upheaval. The Portuguese was occupying

the Mediterranean and the Atlantic coasts of Morocco. It is believed that this

was the period when he composed Dala’il al-Khayrat as an assembly of prayers

upon the Prophet Muhammad. He initiated a Sufi circle of Shadhiliyyah. Those who

were close to Imam Al-Jazuli and became frequent in attending his circles of

learning amounted to 12,665 disciples.

The Recital and

Ijaza: The recitation of Dala’il al-Khayrat was welcomed by Muslim

societies in the East and West. Today, these salawat upon the Prophet Muhammad

are still performed individually, besides, in public gatherings in mosques. The

recitation of the whole Dala’il al-Khayrat in one sitting may take up to two

hours, with a consistent rhythm. Such gatherings are usually conducted annually

especially during the Maulid, in remembrance the birth of the Prophet.

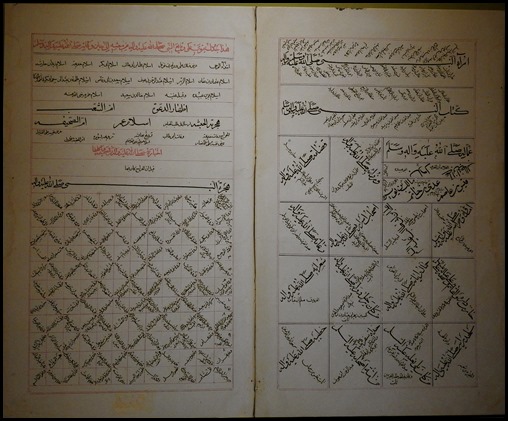

In the classical tradition, ijaza in

reciting the Dala’il al-Khayrat was granted by the shaykh (master) to his

disciples. During this session, the shaykh will listen to the recitation of his

disciples and make any corrections needed. The shaykh will also emphasise on the

adab, the manner of recitation. By obtaining the ijaza, it means that the person

is qualified for reading and leading his own circle of recitation. He may also

become the reference in teaching the salawat. The continuous lineage of ijaza,

that traced the chain to Imam Al-Jazuli are also included in copies of Dala’il

al-Khayrat.

Al-Sahifa

Al-Kamila Al-Sajjadia Prayer Book. Qajar, Iran. 1851. Qasidah Al-Burdah. Mamluk probably Egypt or Yemen.

1526.

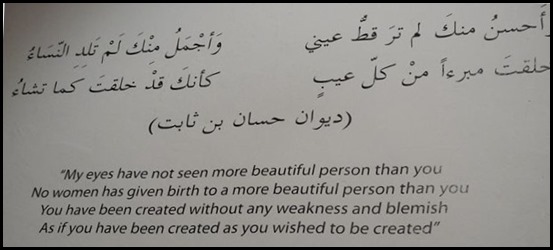

Diwan Hassan ibn

Thabit.

The

Spiritual _expression_: The love for the Prophet Muhammad has

become an inspiration to many Muslim poets around the world to compose adequate

verses of poetry expressing their love and affection to the Prophet. Hundreds of

poems dedicated to the life, message and miracles of the Prophet were composed

in different languages, some of which were translated into different other

languages and some had influenced the authorship of others.

Hassan ibn Thabit al-Ansari was among

the closest companions of the Prophet Muhammad. Besides his role as the scribe

of the Prophet, Hassan ibn Thabit was the notable poet who first composed

madih, beautiful poetry to praise the Prophet. Hassan ibn Thabit’s

poetry has spread throughout the world, and has been memorised by thousands of

people and chanted in social gatherings.

Kitab al-Mawlid

al-Nabawi. Ottoman, Makkah. 1633.

The Chosen Prophet:

The Prophet Muhammad was born in Makkah around 570 AD. His father, Abdullah,

died before his birth and his mother, Aminah, died when he was about six years

old. He was placed under the protection of his grandfather, Abd al-Mutallib

until the age of eight. Abd al-Mutallib was an influential leader of the Arab

tribe, Quraysh. After his grandfather passed away, the Prophet was then

entrusted to his uncle, Abu Talib. As a young man, like many other Makkans, the

Prophet Muhammad became engaged in trading. At the age of twelve, he accompanied

his uncle, Abu Talib in a merchant caravan as far as Busra in

Syria.

After hearing about the unimpeachable

character of the Prophet, which gives him the title ‘Al-Amin (the Trustworthy),

Khadijah, a wealthy woman, hired him to carry out her business to Syria.

Impressed with his sincerity and honesty, Khadijah soon married him. They were

blessed with four daughters and three sons who died in infancy. At the age of

forty, the Prophet Muhammad received his first revelation. The revelation

continues for twenty three years, collectively they are the Qur’an.

In the year 610, the Prophet lost his

wife, Khadijah, and uncle, Abu Talib. Two years after that, the Prophet migrated

to Madinah, This migration marks the beginning of the Muslim era. In 632 AD, the

Prophet Muhammad returned to Makkah to perform hajj, the pilgrimage. During this

event, the final revelation came upon him. The Prophet Muhammad passed away in

the same year in Madinah. His tomb is located in the Prophet;s Mosque, in the

area called the Rawdah.

Tuhfat

al-Khaqan. Qajah, Iran. 1818 AD.

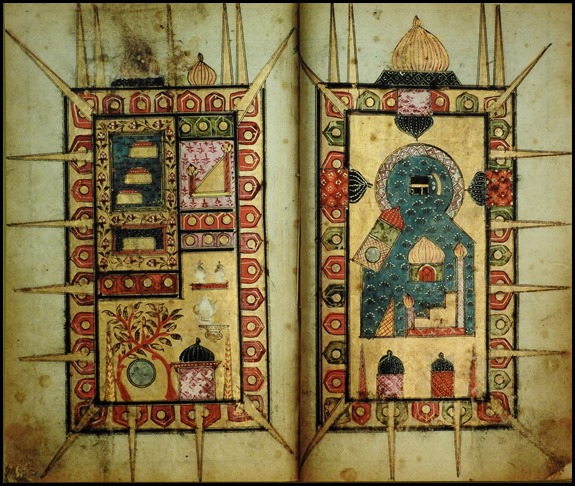

Dala’il al-Khayrat. Ottoman Egypt or Turkey. 1862. These illuminated pages

mark the beginning of the recitation on Sunday.

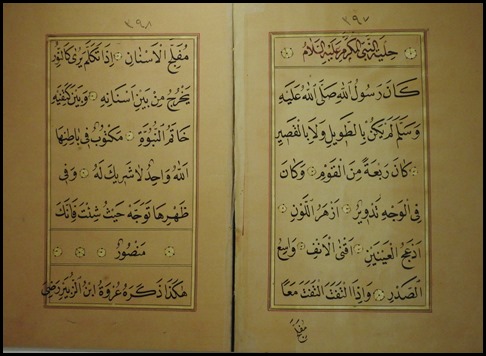

Inside Dala’il al-Khayrat: The full

title as recorded in the manuscripts is Dala’il al-Khayrat wa Shawariq al-Anwar fi Zikr al-Salat ala

al-Nabi al-Mukhtar. It can be loosely translated as ‘Guidelines to the Blessings

and the Shining of Lights, Giving the Saying of the Blessing Prayer over the

Chosen Prophet’. The text of the Dala’il al-Khayrat usually begins with the Muqaddimah, the

introduction that contains the short salawat upon the Prophet Muhammad

and his lineage, the brief explanation on the purpose and objectives of

compiling these prayers as well as the benefits and method of its

recitation.

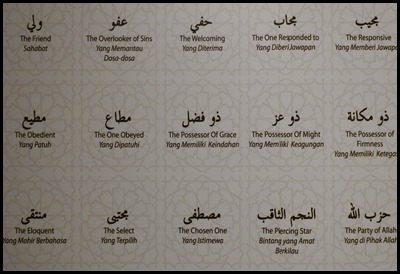

Along with the effort of writing the

salawat, Imam Al-Jazuli has put on an initiative in compiling the 201 names of

the Prophet Muhammad from a great variety of trusted sources and composed them

in a beautiful arrangement. Another significant section in this prayer book is a

brief description of the Rawdah (the burial chamber) inside the Prophet’s Mosque

in Madinah, where the tombs of the Prophet and his two closest companions,

Caliph Abu Bakr al-Siddiq and Caliph Umar ibn al-Khattab are

located.

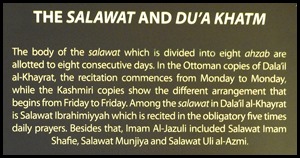

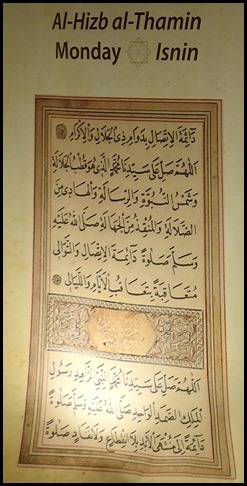

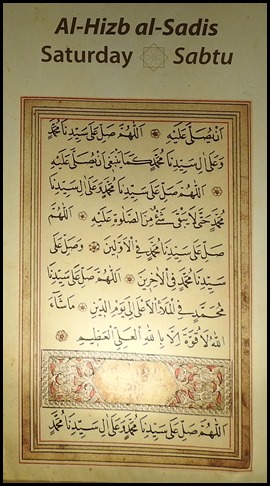

The compilation of Salawat

in Dala’il al-Khayrat is divided into the

days of the week, but with a special addition of one extra day. The

hikmah in dividing the prayers into eight days, instead of seven, remains a

mystery to this day. Each group of the Salawat is called hizb, and it is further

divided into halves, thirds and quarters. The phrase of the salawat

usually begins with ‘Allahumma salli ala’. Indirectly, this phrase declares

Allah as the Creator and the uncountable blessings that He showered upon

mankind.

Beautiful to

look at even though we will never be able to read it.

Embroidered plan

of Makkah. North India, 19th century.

Depictions of the

Holy Mosques in Makkah and Madinah: Images of Al-Masjid al-Haram in

Makkah and Al-Masjid al-Nabawi (the Prophet’s Mosque) in Madinah, mark the final

development of the illustrations in Dala’il al-Khayrat While the rest of the illustrations were

rendered in a two-dimensional flat projection, the images of the Holy mosques in

Makkah and Madinah were executed in prospective view. This shift from a two

dimensional to a three dimensional representation of the mosques was introduced

to the manuscript starting from the second half of the 18th century AD, and

mainly from the Ottoman copies.

The Ottoman style topographical

illustration of the Holy mosques includes architectural details of the site from

a birds-eye view. The Makkah birds-eye illustration depicts different

architectural structures surrounding the Kaaba, among which Maqam

Ibrahim, the schools of the four Sunni sects, the Minbar and the

Zamzam well. Meanwhile, the illustration of the Prophet’s Mosque in

Madinah depicts the domed structure that represents the Rawdah on the

left corner of the mosque compound, the Minbar and the Garden of

Fatima. Adding to this panoramic scene are the mountains, blue skies, and other

architectural edifices.

Although the illustration of

Al-Masjid al-Haram in copies of Dala’il al-Khayrat finds no relation to the text, its presence is

due to the significant role the Kaaba plays as the sacred site for Muslims in

performing the hajj rituals. The facing images of the Holy mosques in

Makkah and Madinah continue to enhance the later lithographed printed additions

of Dala’il

al-Khayrat.

Depictions of Al-Rawdah al-Mubarakah and Kaaba:

The middle of the 18th century AD to the middle of the 19th century AD witnessed

a remarkable shift in the illustration of Dala’il al-Khayrat. A depiction of Al-Masjid al-Haram in Makkah

appeared on the right-hand side, while the images of Rawdah appeared on

the left. The addition of the Kaaba illustration into the Dala’il al-Khayrat have no relation to the text. It finds its

significance as the most sacred place to Muslims and its role as the direction

of prayer.

In copies of Dala’il al-Khayrat, the image of Makkah shows the Kaaba as its

focal point. The Kaaba is illustrated in a black square with Hajr

al-Aswad (the Black Stone) on its left corner. Adjacent to the right side

but not connected to the Kaaba wall is the crescent-shaped structure, known as

Hijr Ismail. The Kaaba is surrounded by architectural elements which

highlight the details od Al-Masjid al-Haram during the period these

illustrations were made. The four schools of Sunni Muslim; Hanafi, Maliki,

Hanbali and Shafie are usually depicted in a domed structure. Another important

element is Maqam Ibrahim, which is usually placed in front of the Kaaba

door. Furthermore, Zamzam well is featured as a domed structure with a

circle in the middle that represents the

well.

The depiction of the Rawdah

developed into different schematic drawings. The additional rectangle unit is

believed to be the depiction of the tomb of Fatimah, the beloved daughter of the

Prophet Muhammad. In various copies of Dala’il al-Khayrat, the Rawdah features additional

elements such as multiple domes and minarets and enhanced with palm trees as to

describe the Garden of Fatimah.

Depictions of the Rawdah and the Minbar: The

description of Al-Rawdah al-Mubarakah, the burial chamber of the Prophet

Muhammad takes up a small section in Dala’il al-Khayrat. In this section Imam Al-Jazuli says: ”This is

the description of Al-Rawdah Al-Mubarakah (the Blessed Garden) in which the

Prophet Muhammad is buried, together with his two companions Abu Bakr al-Siddiq

and Umar ibn al-Khattab.” In reference to this passage, illuminators and

painters in the subsequent centuries have been encouraged to add an illustration

of the Rawdah, which later became the focal point of Dala’il al-Khayrat. This illustration started with a schematic

drawing of the cluster of tombs, represented by three rectangles, that serves as

graphical expansion of the

text.

The second phase of the expansion of

the illustration is when the Minbar (pulpit) and the Mihrab

(qibla niche) of the Prophet were added into the manuscript, complementing the

Rawdah. Usually the Rawdah is painted on the right page of the

manuscript and the Minbar and Mihrab on the left. The tombs

remain in the form of three rectangles. The Minbar is depicted by small

squares arranged in a form of three, four or five steps. This illustration is

commonly laid under an arched niche where a mosque lamp hangs at the centre.

Keeping the two-dimensional flat projection drawing, the illustration reveals

what is significant in the North African and Middle Eastern schematic portrayal

of the Rawdah and the Minbar. In North Africa, the tradition

remains; copies of Dala’il al-Khayrat continue to depict

the illustration of the Rawdah and the Minbar until the 19th

century AD.

Veneration of the Prophet: The love towards the

Prophet is concerned with one’s faith. In the Shahadah, Muslims declare

the oneness of God and accept that the Prophet Muhammad is His Messenger. It is

through him that Allah sent his message of Islam to all humanity. One of the

ways to express love towards the Prophet is by knowing and understanding the

chronicles of his life account. Narratives of the Prophet’s life account can be

extracted from various religious treatises, especially the Sirah al-Nabi (Life

of the Prophet and numerous versions of Kitab al-Maulid, the book on the birth

of the Prophet. Other treatises, that speak of the Prophet’s noble genealogy and

qualities as well as indulge in emphasising the miracles that he possessed, are

placed under the genre of Dala’il al-Nubuwwah (Proofs of the Prophethood) and

Syama’il (expositions of the Prophet’s qualities and outward

beauties).

The Prophet Muhammad’s personality is

regarded as a perfect model of human conduct and behaviour. The Qur’an addressed

him as ‘uswatun hasanatun’, which means a beautiful example. For centuries,

Muslims have sought to emulate the sunnah, the way of the Prophet’s life. He was

adorned with the best qualities and good manner. He was very gentle in his

utterance. His love to others knew no bounds; he showed compassion and mercy to

his family and all people regardless of their backgrounds and belief. Equal

admiration and high esteem were shown towards him even by those who did not

believe in his message. Even before his prophethood, the people in Makkah

admired him for the truthfulness of his speech until he was given the epithet

‘Al-Amin.’ the Trustworthy.

Some of the 201 names

for the Prophet Muhammad.

We left the gallery and crossed to the

crisp, gorgeous restaurant beyond the fountain for a

cold juice then spent a while in the shop – so many

beautiful things.

ALL IN ALL TREASURED AND HOLY

BOOKS

BEAUTIFUL CALLIGRAPHY

|