Old Royal Naval College

Beez Neez now Chy Whella

Big Bear and Pepe Millard

Tue 22 Aug 2017 22:37

|

The Old Royal Naval College,

Greenwich

Next to the Cutty Sark is a gorgeous

building – the Old Royal Naval

College, we thought we would nip in en route to the

Observatory.

A surprisingly modern, airy space.

The Royal Naval College opened on the

1st of February 1873. Its aim was to provide “the highest possible instruction

in all branches of theoretical and scientific study” necessary to the Navy at a

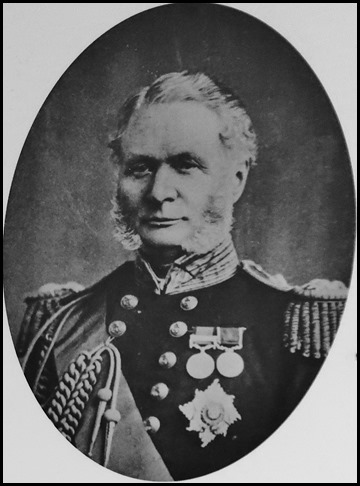

time of rapidly changing technology. The first President, Vice-Admiral Sir Astley Cooper Key, believed that officers should be

highly trained to provide the right leadership qualities. The senior training

staff and directors of studies were the foremost experts in their fields,

further reinforcing the rigorous academic standards. The college quickly became

the most highly rated naval officers’ training college in Europe. As its

reputation grew, students from navies around the world came to study in

Greenwich, with officers from Russia, Japan and China among the first

arrivals.

Students

ranged in rank from Acting Sub-Lieutenant to Captain. There were also Royal

Marine Officers, dockyard apprentice scholars and Merchant Marine Officers.

Later, selected Army and Air Force officers joined the Naval Staff Courses as

well as officers from many other countries.

Occasions: In 1939 the restored Painted Hall was reinstated as the Officers’ Mess. During

term time the College held regular guest nights when nearly 400 sat down to

dinner. The setting, with long rows of polished tables and the silver gleaming

under the light of the candlesticks, provided a spectacle that no other mess

could rival.

Many distinguished visitors were

entertained. For example, in 1942 Winston Churchill attended a dinner with US

government personnel and Senior Naval staff. In January 1946 the Painted Hall

was chosen for the first dinner of the newly formed United Nations. Another

memorable occasion was the 150th anniversary of the Battle of Trafalgar on the

21st of October 1955, which was attended by The Queen and the Duke of Edinburgh.

(menu and

bits above).

Officers playing croquet on Grand

Square. The Royal Naval College courses were demanding

so it was important for students to have time off, and leisure activities were

encouraged. A variety of sport was played, including squash (using the courts

then in this building), hockey, cricket, croquet and tennis. Social activities

included a thriving dramatic society, which staged numerous plays, billiards,

Highland dancing and skittles in the Victorian skittle alley beneath the Upper

Grand Square.

The Greenwich Night Pageant held in June 1933 was staged on an

extraordinary scale. Masterminded by Admiral President Barry Domvile. It

featured over 2,000 performers who recreated scenes from Greenwich’s history

such as Queen Elizabeth I knighting Sir Francis Drake and Nelson’s funeral

procession on the River Thames. Admiral Domvile was a fascist sympathiser and,

after retiring from the Navy, was interned during World War

II.

The War Years: World War I saw a

change of emphasis in the courses offered at the Royal Naval College. It was

used partly as a barracks and partly for experimental scientific work, including

the production of vaccines. The end of the war brought further changes and

considerable expansion, including the addition of History and English

Departments and the creation of a Royal Naval Staff College in

1919.

The outbreak of World War II in 1939

changed the College’s main role to providing rapid training of ‘hostilities

only’ officers with additional courses in cryptography, meteorology, navigation,

air intelligence and current affairs. Nearly 27,000 officers passed through the

College during the war years, including 14,000 from the Royal Naval and Royal

Naval Volunteer Reserves and more than 8,000 WRNS officers (Women’s Royal Naval

Service).

During the blitz the clearance of

debris from fire and bomb damage, for the most part minor, became a daily

routine. During air raids students were confined to the cellars, where there

were bunk beds. The picture above shows bomb damage to the

King Charles Court in 1943.

The Royal Naval

College with its lights blazing for the first time in years, VE (Victory

in Europe) Day, 8th of May 1945.

Layout.

After 1945 the College expanded its courses in engineering and science,

including for the first time nuclear technology.

Harley made a beeline for replica

Tudor armour which Bear helped him put on. The

Gauntlet is based on a design manufactured at the Greenwich Armour

Workshop in about 1520. The overlapping plates made it easy for the wearer to

hold any weapon. It extends far enough to cover the veins in the wrist. The Frogmouth Helm is also based on a design from around

1520, this jousting helmet extends far down onto the shoulders to brace the neck

during a joust. The vision slit is small because it was very important that no

splinters from a broken lance could get into the wearer’s eyes. A guide came

along just then and explained that the smooth upward curve to the eye slit meant

that contact from an opponents lance would skid up and over the helmet rather

than cause damage the eyes (all well and good so long as the opponent at full

gallop didn’t break your neck, methinks.......).

Model of a

tiltyard.

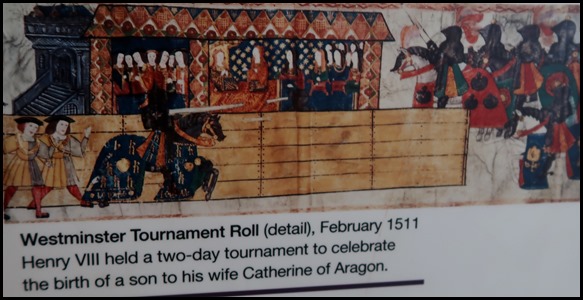

Henry VIII was an expert horseman and

loved jousting (hard to imagine as the only pictures we ever see of him is that

of a rather portly sort....). He built a permanent tiltyard at Greenwich in

1516, just south of the Palace, in the area just north of where the Queen’s

House stands today. It was very large – around 198 metres long by 76 metres

wide, with a surface that was soft, to cushion the fall of an unhorsed knight or

horse. Down the centre was the ‘tilt’, a wooden wall around two metres high

which prevented the two charging jousters from crashing into each other. West of

the tiltyard were two tall brick towers next to the spectators’ stands, the

foundations of which survive under the lawns of the Queen’s House.

Jousts were great spectacles and

often served as entertainment for important foreign dignitaries. In addition to

the excitement of watching the joust, spectators had an opportunity to observe

the royal family and nobility. The viewing gallery was hung with rich tapestries

and there were cushions for the royal family and important visitors to sit upon.

The commoners, who often came by the thousand, had to find the best place they

could.

Jousting was a sport practised by

knights on horseback. Two armoured jousters charged at each other, the aim being

to hit one another with their wooden lances as hard and as accurately as

possible. There were two main targets: the head and the shield or body. Hits to

the head were worth more points, reflecting the fact that it was much harder to

hit. An ‘attaint’ was a good hit that did not break the lance. A lance smashed

to pieces on the head or body gave a higher score than an attaint, as it was a

dramatic demonstration of power and skill. If a jouster managed to knock his

opponent off his horse, he was awarded additional points or won the contest

outright.

Jousts were vital opportunities for

kings, princes and knights to display their lance-combat and riding skills. They

were held to honour foreign ambassadors or to mark special occasions such as

marriages and births. At the heart of these combat

festivals was chivalry – the knight’s code of behaviour that required noble

ladies to be treated with great respect and reverence. Women played an important

part in jousts. Knights tried to impress them as they often served as judges.

Noblewomen often gave their support in the form of scarves (favours) to their

chosen knights.

The Greenwich Royal Workshop was the

first of its kind in England. It was founded by Henry VIII in 1515 to create an

armour workshop to rival those of Germany and northern Italy. Henry engaged

Almain (German and Netherlandish) armourers and built a workshop to the west of

the Palace. A steel mill set up in nearby Lewisham provided the raw materials.

Greenwich

armour quickly became highly prized. It reflected the status, wealth and

taste of its wearer. During Henry VIII’s reign, armour made at Greenwich was

intended for the King’s personal use or was given by him as an impressive

diplomatic gift. Later, all orders for Greenwich armour had to be signed by the

Queen Elizabeth I herself. The royal armourers had gained an interntional

reputation for their superb aesthetic designs and technical craftsmanship. They

also worked closely with court artists: for example, the decoration etched on

some of Henry Viii’s finest suits of armour was designed by Hans Holbein.

By the mid-17th century, armour was

starting to be viewed as old-fashioned and obsolete and armour production at

Greenwich declined, both in quality and quantity. In 1649 Parliament closed the

Royal Workshops and transferred its contents to the Tower of

London.

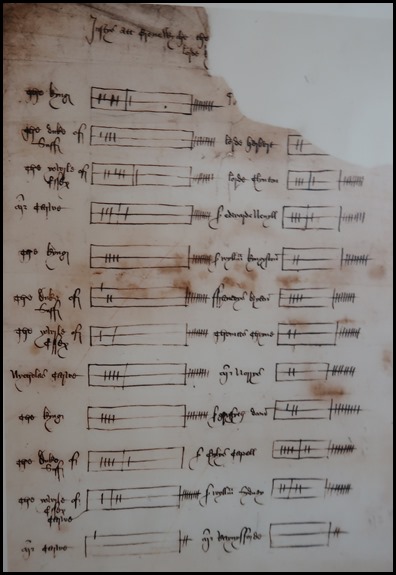

A score cheque

from a joust held at Greenwich, May 1516. The marks indicate the areas of

the body struck during individual passes or ‘courses’. The position within the

box corresponds to the area of the body that has been hit: a mark on the top

line records a head-hit, while one on the middle line indicates a blow to the

body. The bottom line was used for foul or illegal strikes. The marks on the

line to the right of the box record the total number of runs by that particular

jouster.

Time to leave this interesting museum with a look at a

model one of the domes.

The trigger

finger looks rather grand with the Cutty Sark as a backdrop. This Turkish

bronze gun was cast in 1790-91, in the region of the Ottoman Sultan Selim III.

It weighs 5.2 tonnes, fired stone shot of just over 56 kilos and is one of two

taken by Admiral Sir John Duckworth from Kinali Island in the Sea of Marmara in

1807.

The gun was presented to the Royal

Naval Asylum at Greenwich by HRH Prince Ernest, Duke of Cumberland, on the 21st

of October 1807. The cast-iron display carriage was

made by the Royal Carriage Department of the Royal Arsenal, Woolwich. Its

decorative plaques commemorate British naval victories.

In 1821 the Asylum became part of the

Greenwich Hospital School, renamed the Royal Hospital School in 1892. The school

moved to Holbrook, Suffolk in 1933: its Greenwich buildings are now the National

Maritime Museum. The gun also went to Holbrook until returned for display here

in 2007 with financial support from Greenwich Hospital.

As we walked passed en route to the

Observatory we took in the beauty of some of the

buildings.

Coming from Plymouth our favourite had

to be Devonport House.

ALL IN ALL UNCOMMON AND

INTERESTING STUFF

A BEAUTIFULLY PRESERVED BUILDING WITH MODERN

DISPLAYS |