Parasite Museum

|

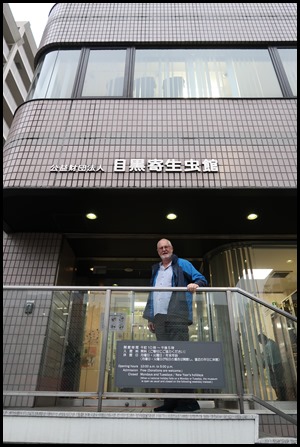

The Parasite Museum, Meguro,

Tokyo

Today is my choice, tomorrow is

Bear’s. So, this girl has the entire eight hundred and forty five square miles

to choose whichever venue appeals – what did I choose ??? The Parasite Museum

(well it it the only one in the world) followed by Tokyo Station. We made our

way to Meguro Station, asked for directions and a kindly Policeman pointed the

way. A ten minute bimble saw us cross a river, walk

over a road and there we were at the museum.

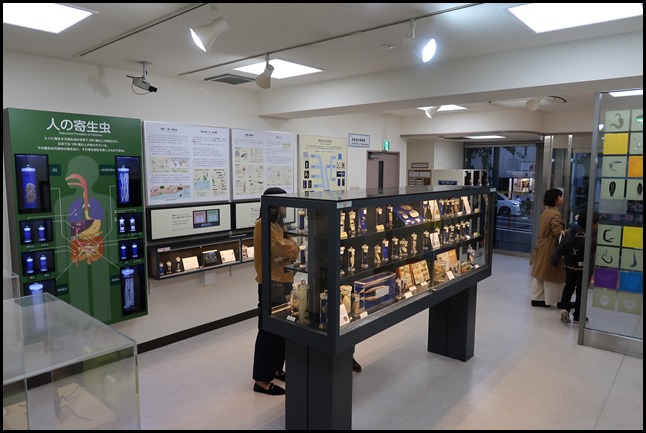

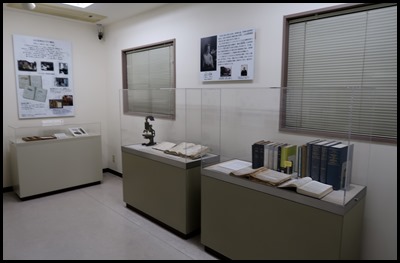

Downstairs............

...............and upstairs. Small but perfectly formed.

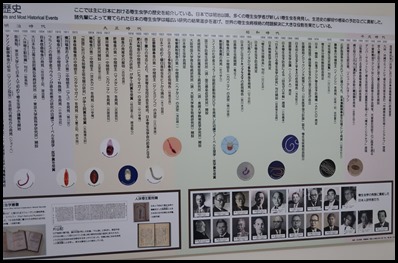

A small room

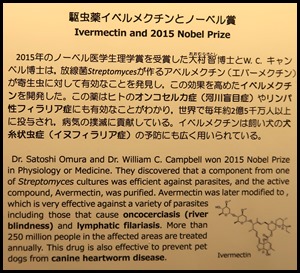

off the main one (upstairs) had a wall dedicated to major

breakthroughs in Japanese parasitology, the rest was dedicated to a man we both know – well his work.

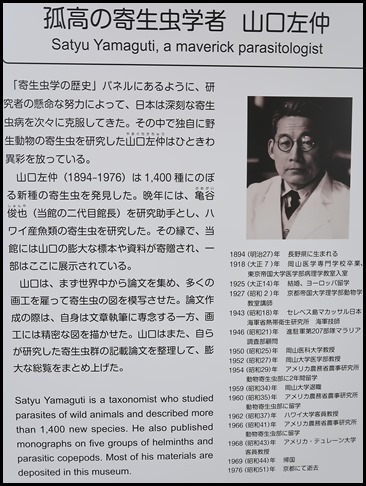

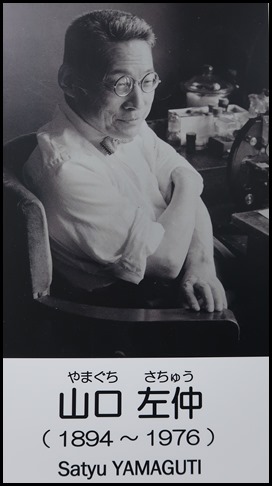

Dr Satyu

Yamaguti, described here as a maverick parasitologist.

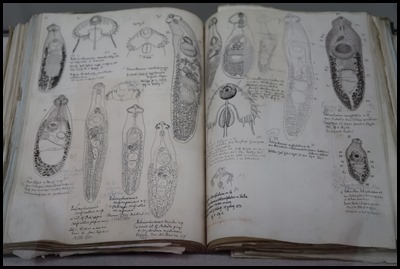

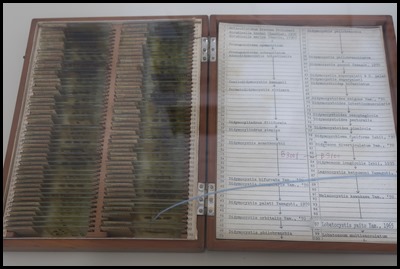

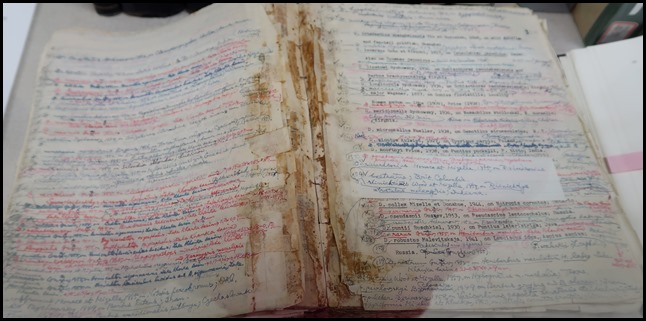

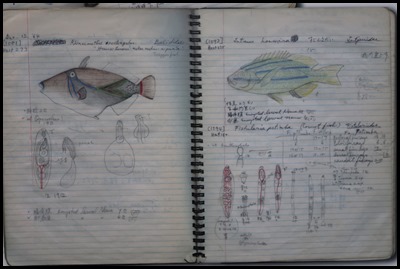

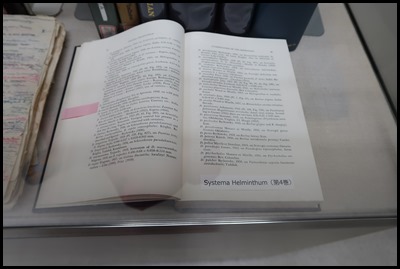

It was lovely to see his handwritten ‘Answer Book’ and

just a sample of his many slides.

Notes

that ended up in his books.

Books Bear

studied and I loved to look through in the library.

Microscope,

man and discovery (Echinococcosis

multilocularis).

Back in the main room we

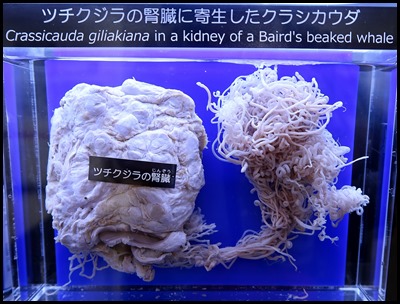

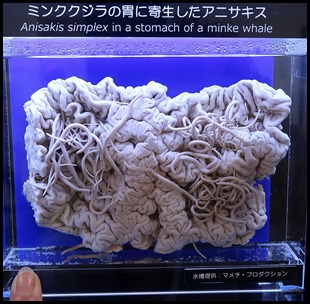

found ‘things’ of

interest.

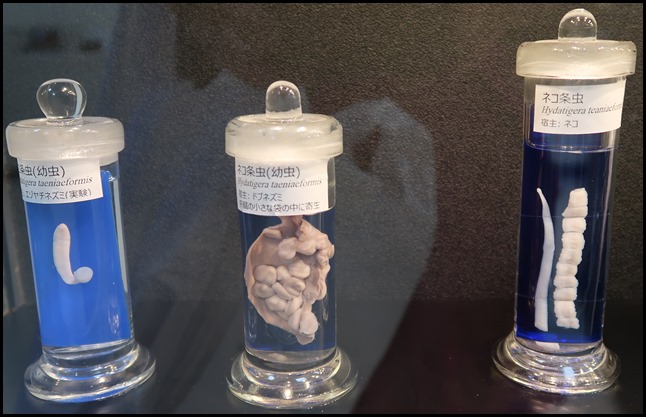

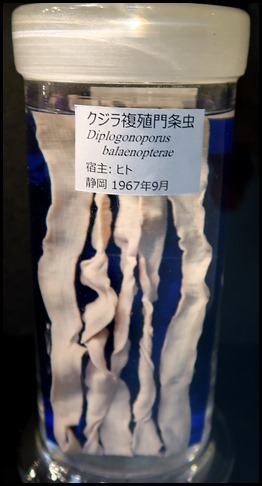

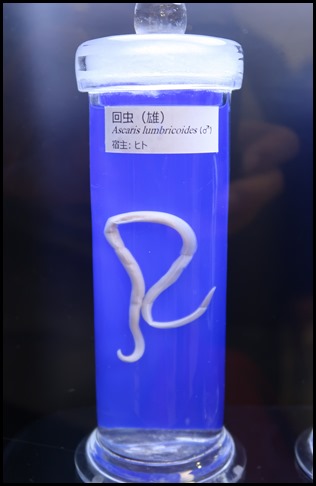

Some

articles had translations.

Others we had to depend on Latin. Bear had a patient visit carrying the chap in the middle – only much longer – in a tissue, the Dangers of Dartmoor I

called it. He kept it in a specimen pot for years....as one would......just goes to show that two days

are never alike, methinks.

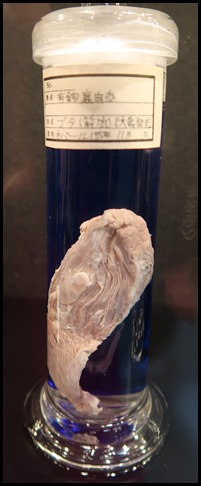

Some will remain a mystery.

Researching the museum, opening times

and whatnot, I found an article that had appeared in the Japan

Times.

Strange world of parasites on display

Published on the 11th of March 2001

While the Meguro Parasitological Museum may at first seem little more than a freak show, visitors soon learn more about the profound nature of these strange creatures. “I guess they come here through curiosity to see the gross stuff but they become rather serious once they start observing the displays,” curator Jun Araki said. “There is no screaming heard.” According to Araki, the museum is the world’s only institute dedicated to showcasing parasites. It was established by a local general practitioner, Satoru Kamegai, in 1953.

Some 300 species of parasites preserved in formalin-filled glass containers are on display, some extremely rare. Among the rarest are the parasites found by 92-year-old Kamegai in the body of a coelacanth. But the most popular parasite with visitors to the museum is, without doubt, the 8.8-meter-long tapeworm extracted from a human body. To provide viewers with a reference point for the size of the tapeworm, the museum has set up a ribbon of the same length and width beside the display. The museum attracts an estimated 70,000 visitors annually — an unusually high number for such a small establishment that has only four full-time staff members and features such a quirky theme. According to Araki, about half the visitors are young people. Young couples, in particular, frequent the venue, while the museum also attracts many school trips, he said. When asked about the popularity of the museum, Araki said, “I don’t know why — maybe because of its rarity.”Hiroko Ito from Sendai, Miyagi Prefecture, and Miyuki Ko from Fukushima decided to spend half of their day trip to Tokyo at the museum rather than opt for the city’s regular tourist attractions. Noting that they do not visit museums often, Ito said, “Well, I guess I was attracted to the 8.8-meter tapeworm.” While the pair of 22-year-old college students showed more than a trace of curiosity in the displays, the parade of parasites also appeared to turn their stomachs. “We should have had lunch before coming here,” they said. “We cannot eat today, definitely not raw stuff.” But this is the kind of response that the museum is struggling to combat, according to Araki. “Some people say they cannot eat raw fish after visiting here but we don’t want them to overreact. “So when I am walking around the museum and overhear this sort of conversation, I poke my nose in and explain that it is safe to eat if you take proper precautions.” Despite its popularity, however, the museum has experienced financial difficulties in recent years. Run by a foundation established by Dr. Kamegai, the museum gains no income through admission fees or sponsors. In order to help make ends meet, a museum shop was opened a couple of years ago. Araki said T-shirts featuring a tapeworm design and key chains in which Anisakis, parasites found in fish and squid, are encased are selling well. Given its financial troubles, many are suggesting that the museum should start charging admission fees. “But how much would you pay?” Araki asked. “Say we charge 100 yen, the number of visitors could be halved. Instead, we want more to come.” While the displays do not have English captions at present, Araki said staff members at the museum are compiling an English guidebook. “Some of us speak English. Just pick up the in-house telephone when you need help,” he said.

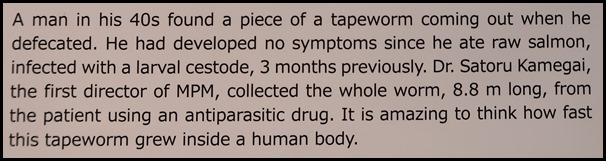

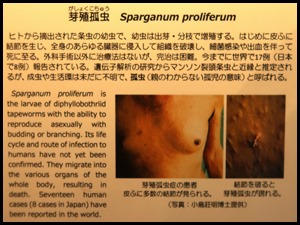

Just to complete the story of the tapeworm, a larval cestode and the write-up.

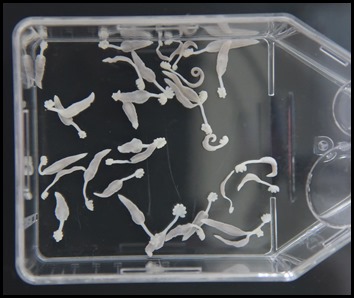

Downstairs – to look at more specimen jars.

A cluster of Neoheterobothrium hirame on the buccal cavity wall of a Japanese flounder, I always did prefer the thought of eating my own flip-flop verses eating raw fish but this poor flounder has knocked the idea further into a cocked hat......

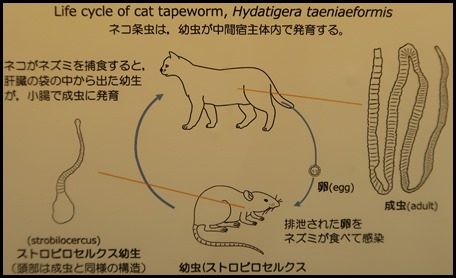

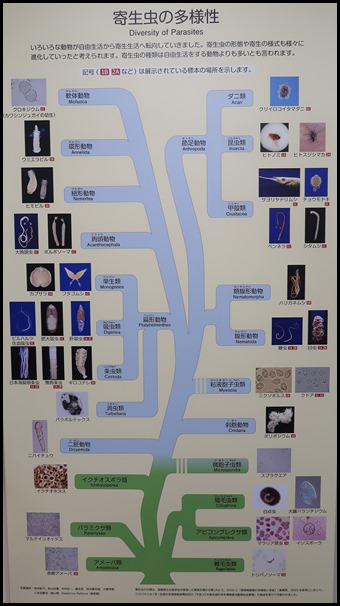

Helpful wall charts and the bell went for closing time. Thrilled to have been here.

ALL IN ALL SOMETHING REALLY QUIRKY AND I LOVED IT WELL THAT WAS DIFFERENT AND I RECOGNISED A FEW OLD FRIENDS........ |