Pūpū Springs

|

Pūpū Springs – the Nuts and

Bolts.

The map. Before

we set off for the springs we read all the information on the stunning glass

panels.

The first

stream we passed had the clearest water and flowed very quickly,

extremely funny to watch the ducks hurtling along. We then set off along the beautifully constructed boardwalk, hopefully this will protect the sacredness with which the Māori

hold this special place.

The well kept gravel

path through the forest, then on to the brilliantly crafted ‘fitted’ boardwalk.

Over the bridge

where we just had to pose and through the last wiggly bit.

And there we were, beside what can only be

described as the most perfect water we have yet

seen.

The deepest parts showed itself in blues, in the nearer shallows we could

see down several feet.

Te Waikoropūpū Springs (known locally as Pūpū Springs),

discharges fourteen thousand litres of water per second or forty bathtubs every

second, are the largest freshwater springs in New Zealand, the largest cold

water springs in the Southern Hemisphere, and contain some of the clearest water

ever measured.

To local Māori, Te Waikoropūpū Springs are a taonga

(treasure) and wāhi tapu, a place held in high cultural and spiritual regard.

The waters of Te Waikoropūpū Springs, including Fish

Creek and Springs River, are closed to all forms of contact (including fishing,

swimming, diving, wading, boating and drinking the water) to safeguard water

quality and to respect cultural values.

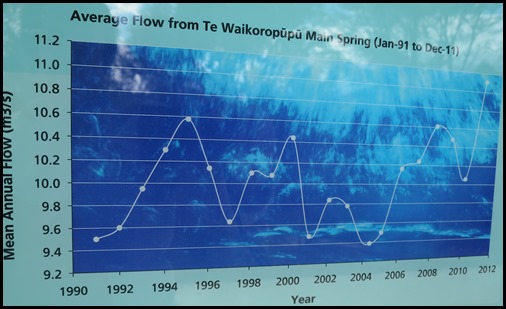

Geology, landform, rainfall, time, chemistry and water pressure come together in a unique mix to create the phenomenon of Te Waikoropūpū Springs. Where does the water come from: Scientists have been debating that question for the past one hundred and twenty years. Here is some of the latest findings, based on decades of research. All the water at Te Waikoropūpū ‘starts life’ as rainfall, but some emerges at the Springs as ten year old water while some emerges as one year old water why ???

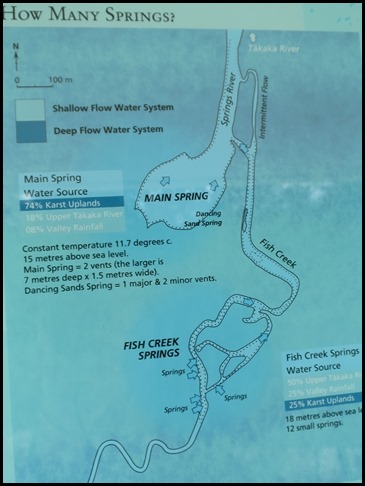

There are two groups of springs at Te Waikoropūpū Springs. The Main Springs – that includes Dancing Sands Spring and Fish Creek – made up of twelve springs. Most of the water emerging from the Main Spring comes from the Karst Uplands of the Takaka River and from valley rainfall. In contrast, Fish Creek Springs are mainly fed by the Upper Takaka River with valley rainfall and the Kart Uplands contributing the balance.

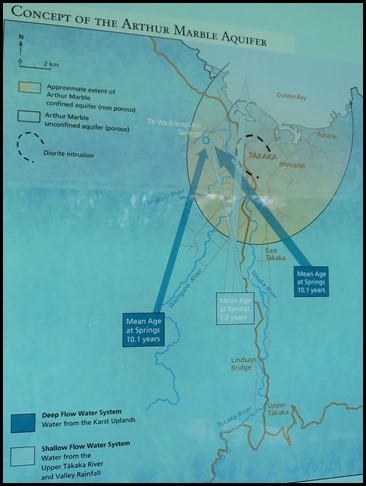

How old is the water? The mean age of the Deep Flow System is ten point two years and the mean age of the Shallow Flow System is one point two years. The different behaviours of the two systems are believed to be due to the presence of a buried diorite intrusion – a block of rock, below the surface of the lower Takaka Valley. This intrusion diverts the deep water flow towards Te Waikoropūpū Springs blocking it from flowing to the sea, thereby separating the Deep Flow System from the Shallow Flow System. Much of the Shallow Flow System travels over the top of the intrusion and escapes via submarine springs. These submarine springs are not defined, discernable springs, they are more like a series of seepages.

Arthur Mable Aquifer: Beneath the surface of the Takaka River Valley – extending up into the mountains and out under the ocean lies a karst formation – an underground maze of interconnecting tunnels, seepages and gravels through which rainwater flows, from the Karst Uplands to the sea. It is called the Arthur Marble Aquifer. Water from the aquifer recharges Te Waikoropūpū Springs. Water from the Karst Uplands, along with water from the Upper Takaka River and water from Valley Rainfall – surface rainfall, all contribute to Te Waikoropūpū waters. The qualities of the water from Te Waikoropūpū Springs are of considerable scientific interest. In 1993, The National Institute for Water and Atmosphere (NIWA) carried out optical measurements under water and found that the visibility was sixty three metres. This is very close to optically pure water, with clearer water found only beneath Antarctica’s near-frozen Weddell Sea. The water clarity is a result of natural filtering prior to the water’s emergence at Te Waikoropūpū Springs.

Tidal Flux: The springs exhibit remarkable twice-daily fluctuations in flow. These correspond to local marine tides, despite the fact that the springs are fifty metres above sea level and there is no known connection to the sea. Scientists at NIWA have shown that the tidal effect is caused by both ocean-loading tides (the movement of the Earth’s crust in response to ocean tides) and Earth tides (the movement of the Earth’s crust as a direct result of gravitational attraction to the Sun and Moon). The possibility of a subterranean connection to the sea is suggested by chemical measurements showing that sea water is present in the discharge. Salt water makes up .05% of the water in the Main Spring. Salt water underlies the Arthur Marble Aquifer at all times. During periods of heavy rain, the pressure of more water in the deep flow system creates a venturi effect that sucks salt from lower levels to infiltrate the system. Due to the Deep Flow System and the Shallow Flow System being separated, salt water is not drawn into the Shallow Flow System.

History: Māori probably first visited this area over seven hundred years ago as part of a gradual expansion from Nelson through Tasman Bay and Mōhua (Golden Bay) to the West Coast. When Colonel William Wakefield arrived in 1839 to buy land for the New Zealand Company, he estimated that there were two hundred and fifty people living in Mōhua, representing the Ngāti Tama, Te Ātiawa and Ngāti Rarua tribes. Many of their descendants still live in Mōhua and as mana whenua of Mōhua, have traditional rights at Te Waikoropūpū.

Part of the Te Waikoropūpū Springs walking track follows the line of an old water race that delivered water from a dam at Fish Gully to gold workings near Main Spring. Early European settlers arrived in the Golden Bay area in the 1830’s, mainly to build ships and mine for gold, coal and lime. Originally the area around Te Waikoropūpū Springs was covered in lowland forest. Gold miners cleared the forest to build water races for sluicing alluvial gold and a mining company worked the area until about 1910. Few records remain to indicate the exact scale or success of the gold mining ventures that operated near the springs but it was doubtful that hydraulic sluicing was utilised. Hydraulic methods were used in the Waikoropūpū Valley by the profitable Takaka Hydraulic Sluicing Company who worked Campbell Creek from 1901-1908. Their water race, over one kilometre in length, was recommissioned in 1929 to serve a power station built by the Golden Bay Power Board. Today’s Pūpū Walkway, accessed from the Waikoropūpū Valley Road, follows the line of that early race and takes in the penstock and the power house that was rebuilt in 1980 by the Pūpū Hydro Society to generate electricity for the National Grid.  1940.

Following the brief goldmining flurry

of the 1850’s, the land around the springs was claimed by the Crown. It was sold

into private ownership for farming and after changing hands several times was

purchased in 1912 by the Takaka Sluicing Company’s manager, Charles Campbell.

Campbell’s daughter Hilda subsequently inherited the land. Hilda Campbell

recognised the international importance of the springs and sold nine acres to

the Crown in 1979 on condition that the springs were preserved and managed for

the New Zealand public.

1961. The remnant of native forest left untouched by earlier goldminers and farmers can be seen, flanked by lower growing regenerating forest of which manuka is dominant.

Tourists started visiting the springs in the early days of European settlement, enticed by the scenic photographs of Fred Tyree and word-of-mouth recommendations from those who ventured to the springs on horseback. Some time in the early 1900’s a viewing platform was built, setting an elevation style of looking down into the main spring that remained until 1984. Diving was a drawcard for many during the second half of the 1900’s.Divers came from all over the world to experience the unique, aquatic environment and clear waters of the springs. Since 2007 the waters of the reserve have been closed to the public.In 1984 the jetty style platform was built with a periscopic box to assist underwater viewing. The box was intrusive and never highly successful for viewing the underwater world. It was removed in 2012.

Forest in Recovery: Most of Waikoropūpū Springs Scenic Reserve is covered in mānuka and kānuka; indigenous plant ‘pioneers’ that re-colonise cleared forest areas and eventually make way for other species. This vegetation type reflects a history of disturbance by fire, gold mining, farming and road building. The reserve now has areas of regenerating beech-podocarp forest and a small remnant of tall podocarp forest to the south of Te Waikoropūpū Springs. Besides tawhai (black beech), this area features rimu, kahikatea, tōtara, mataī and miro. Te Waikoropūpū Springs is also a habitat for submerged mosses and liverworts, including at least one moss that is found nowhere else.

Bugs, Bullies and Birds: The springs contain many indigenous macroinvertebrates, some rare or with very restricted ranges. These are prey to long-finned and short-finned eel, upland bully, red-finned bully, kōaro and a healthy population of giant kōkopu, one of New Zealand’s most threatened native fish.

ALL IN ALL A UNIQUE WONDER BEAUTIFUL WATERS |