Observatory Stuff

Beez Neez now Chy Whella

Big Bear and Pepe Millard

Mon 7 Jul 2014 22:47

|

Stuff from the Observatory – If you read this, you really have

to get out more...........it’s for me – however the Māori Bit at the End is

Interesting.  13.7 BILLION YEARS

BACK............ OK that caught my attention, has someone studied the

time when Bear began to snore.........to the moment when it burst onto being out

of the void. The Big Bang. Oh. I haven’t listened to my Albert Einstein or

Stephen Hawking audiobooks yet, so this was fascinating for me to learn about

things that I have no grasp of. We watched some short videos with comments from

men with brains the size of Britain, I followed them on stars, galaxies, the

Universe and was quite excited that I could keep up, that was until the comment

in Black Holes when the chap said ”when space and time turns in on itself” –

what........Here’s what I did understand.

13.7 billion years ago the Universe burst

into being., expanding from a single point – the Big Bang. How do we know?

Because we can see that it is still expanding. When we look at faraway galaxies,

we can see that they are moving away from us very quickly. If the galaxies are

moving apart, they must have been densely packed together in a tiny space. By

calculating how fast the Universe is expanding – and making allowances for the

evidence that this expansion may have sped up over time – astronomers can

calculate when the Big Bang happened.

0.000000000000000000000000000000000000000001 seconds after the Big

Bang the Universe was this size.

The Void: It’s impossible

for us to know what happened before the Big Bang, because space and time did not

exist. As Saint Augustine put it in the 5th century, “there was no ‘then’ when

there was no time.” The Universe itself, emerging from the timeless void,

created space, time and energy.

Time: After the Big Bang,

the cosmic clock began to tick. After the tiniest fraction of a second, a

ten-trillionth of a quadrillionth of a second, to be precise – the entire

Universe would have been contained within a single grain of sand. A microsecond

later, it measured 100 billion kilometres across – nearly 700 times the distance

from Earth to the Sun.

In the first seconds after the Big Bang

the Universe was far too hot for matter to form. But from the moment it started

expanding, the Universe was cooling down. Within five minutes, the Universe had

cooked up electrons, neutrons and protons – the basic ingredients needed to make

matter.

Light: When electrons,

neutrons and protons first formed, there was still too much energy for them to

come together to make atoms. Instead, they seethed and swirled in a super-heated

soup. Photons – particles of light – zigzagged from one charged particle to the

other, unable to escape. Then, about 300,000 years after the Big Bang, it became

cool enough for the positive and negative particles to stick together. The first

atoms formed. The cosmic fog enveloping the infant Universe became transparent

and there was light.

Cosmic Microwave Background

Radiation: The cooled down light left over from the Big Bang is still

shining all around us. But the expanding Universe has stretched it so much that

we can’t see it at all – we can only detect it as microwave radiation. Theorists

predicted the existence of the cosmic microwave background radiation in 1948.

Two decades later, two radio astronomers investigated a mysterious hiss caused

by interference in their receiver. At first they thought poo from pigeons

nesting in their antenna was to blame for the background noise. Finally, after

ruling out all possible sources, they realised that what they were hearing was

an echo of the Big bang itself. When we tune between stations on the radio,

about 1% of the static we hear is from the same source.

A Lumpy Universe:

Spacecraft and satellite missions have found tiny variations in the cosmic

microwave background radiation – evidence of the microscopic irregularities in

the early Universe. It was those irregularities that would allow matter to clump

together to form galaxies, stars, planets...... and us.

Matter: When particles

created in the first five minutes after the Big Bang joined up 300,000 years

later, they created the two simplest and lightest atoms – hydrogen and helium.

Hydrogen is by far the most common element in the Universe, making up over 74%

of all matter. Helium makes up nearly all the rest – 23%. All the other elements – the carbon in our bodies, the oxygen we

breathe and everything else – make up just over 2%, and were made long after the

Big Bang, in stars.

A photograph

of Something We Can’t See: We can’t see dark matter, because it

doesn’t reflect or emit light. But it can be detected indirectly through its

gravitational effects on stars and galaxies.

Dark Matter:

Astonishingly, the ordinary matter that we, and everything we can see or touch,

are made of seems to be only part of the story. Astronomers have calculated that

there is not enough ordinary matter to generate the gravity needed to hold

galaxies together. There is something else out there, something massive we can’t

see – dark matter. Some dark matter is stuff we know but can’t see because it

doesn’t shine, like black holes, dim stars and planets. But most of it,

astronomers believe, is an exotic form of matter we haven’t yet

identified.

Dark Energy: Since the

early 20th century, astronomers have known that the Universe is expanding. More

recent observations tell us that the expansion is actually speeding up. Dark

energy is the accelerator that’s stretching space, overriding the ‘brake’ of

gravity. What is it? We simply don’t know. Dark energy could be a radical form

of matter, a type of anti- gravity force, or simply a mysterious property of

space itself. Whatever it is, dark energy is locked in an eternal arm-wrestling

competition with gravity. About six billion years ago, it seems that dark energy

began to prevail – and it’s been pushing the Universe outwards at an increasing

rate ever since.

Ordinary matter makes up about 4% of the

Universe’s total mass/energy. Dark matter makes up 22%. Dark energy makes up

74%. But most of the Universe is simply empty space. If the Universe was the

size of the Observatory in which we are now standing – people, stars and

galaxies – would fit within a single grain of sand. I think I now know I need to

get out more........

How will the Universe end ?

Whimper: If dark energy

wins its battle against gravity, the Universe will continue to expand forever,

becoming more and more diluted by empty space. Many billions of years from now

the Universe will become totally cold. Black holes will evaporate and the stars

will go out.

Bang: If, on the

other hand, the Universe contains enough mass, the current expansion will

ultimately slow down, halt, and then reverse as it collapses under its own

weight. Everything in the Universe will crunch back into the infinitely small

point from which it began.

Maybe it won’t? Some

physicists have theorised that our Universe is in fact just one of an infinite

number of universes, known as the Multiverse. One prediction of the Multiverse

theory is an endless series of Big Bang, as universes collide in multiple

dimensions.

The Hubble Ultra Deep

Field is a photograph of a tiny patch of the night sky, taken by the

Hubble Space Telescope. Almost every dot of light is a distant galaxy. The most

distant galaxies are seen as they were nearly thirteen billion years ago,

because that’s how long it has taken for their light to reach

Earth.

Galaxies are

large structures of stars, dust and gas, bound together by gravity. There are

hundreds of billions of galaxies, containing almost all the Universe’s visible

matter. They are threaded through the Universe’s vast empty voids in filaments

and clusters many billions of light years long. Galaxies vary in size from dim,

sparsely populated dwarfs to huge elliptical galaxies, jam-packed with trillions

of stars. All are believed to be surrounded by vast haloes of dark

matter.

The Discovery of Other

Galaxies: Until the early 20th century, many scientists believed that

our galaxy, the Milky Way, was the Universe. As early as the 18th century,

astronomers had noticed faint smudges of light too blurry to be stars – but not

moving, like a comet would be. But there was no way of proving whether these

strange luminous objects were within the Milky Way or outside it. It wasn’t

until 1923, when the American Edwin Hubble used the

most powerful telescope of the time to observe one of these hazy clouds of

light, that the question was settled. What Hubble saw in it was a type of star

whose real brightness was known. By measuring how bright it appeared to us on

Earth he could calculate its distance from us.

His conclusion: It was

far, far outside the Milky Way. In other words, it was another galaxy –

Andromeda. Suddenly, the Universe was much, much bigger.

A Galactic Tape Measure:

The stars Hubble used to measure the distance to the Andromeda galaxy are called

Cepheid variables. Their brightness varies at regular intervals in cycles that

range from days to months. While studying a group of Cepheid variables in the

Large Magellanic Cloud, Harvard astronomer Henrietta Leavitt discovered that the

length of each star’s cycle was directly related to its brightness. The longer

the pulse, the bigger and brighter the star. By noting the length of a Cepheid

variable’s cycle, astronomers can tell how bright it really is. And by

measuring how bright it seems to us on Earth, they can determine how far away it

is.

Clouds of star-forming matter are known as

nebulae. Triggered by shock waves caused by an exploding star, or some other

kind of galactic disturbance, cold gas and dust in the nebula clump together to

form a cluster of proto-stars. Squeezed by gravity, hydrogen atoms in each

proto-star’s core start to fuse in a violent series of nuclear, reactions,

releasing enormous amounts of energy. A star is

born.

Weighty Matters: As the

elements within them fuse together, stars continue the matter-making work begun

in the massive temperatures immediately following the Big Bang. For most of the

star’s life, it is powered by hydrogen fusing to helium in its core. But when

hydrogen runs out, the dying star starts burning its helium reserves. In a star

the size of our Sun, helium fuses to produce carbon, oxygen and nitrogen. In

bigger stars, the process continues all the way up to iron.

As a star exhausts its gas supplies, the

core gets hotter and denser. Heavier and heavier elements form in layers, just

like an onion. In a star twenty five times the mass of our Sun, the hydrogen

burning stage lasts about seven million years. Neon burns over a year, oxygen

over six months, and silicon in the course of a single day.

Hydrogen and oxygen: Each

molecule of water is made up of two hydrogen atoms and one oxygen atom. Hydrogen

is the most common element in the Universe. The hydrogen in this water was formed nearly 13.7 billion years ago, as soon as

the Universe became cool enough for electrons and protons to stick together.

Oxygen is the third most common element in the Universe. These atoms were formed

over 4.6 billion years ago, in a star the size of our Sun or larger.

Silicon is the

second most common element in the Earth’s crust after oxygen. It’s used to make

integrated circuits because it is a semiconductor whose ability to conduct

electricity can be easily adjusted.

Carbon is the

fourth most common element in the Universe. It too is created in medium- and

large-sized stars. Carbon’s ability to form many bonds makes it a key ingredient

of life as we know it.

Iron is the

sixth most common element in the Universe and is created in large stars. The

core of our planet is mainly iron. There’s also an iron atom in each molecule of

haemoglobin, the chemical in our blood that carries oxygen from the lungs to the

body. All the atoms of gold

and silver found on Earth were created in supernovae – the explosive

final moments of huge dying stars – over 4.6 billion years ago.

Death of the

Sun: Our 4.6 billion year-old Sun is a middle-aged, middle-sized star. In

another five billion years, the hydrogen in the Sun’s core will run out. The Sun

will become a bloated red giant and expand to engulf Mercury and Venus, and

maybe even Earth and Mars too. When the dying Sun has exhausted all its gas

supplies, its core will collapse into a tiny, hot mass called a white dwarf,

which will very slowly cool and dim. Its outer atmosphere, containing many of

the new elements it has created over its lifetime, will puff away and disperse

through space, waiting for another cycle of star birth to begin.

The Fate of Stars: The

life cycle of a star – and its fate – are determined by its mass. Stars the size

of our Sun and smaller collapse into white dwarfs made of carbon. Much larger

stars burn out much more quickly, creating heavier and heavier elements, right

up to iron. They also have more dramatic endings, collapsing under their own

weight but then exploding outwards in one of the most spectacular events in the

cosmos: a supernova. All the elements heavier than iron – including gold,

mercury, uranium and lead – are formed in a fraction of a second by the intense

forces generated in the supernova explosion as the greatest of these stars

die.

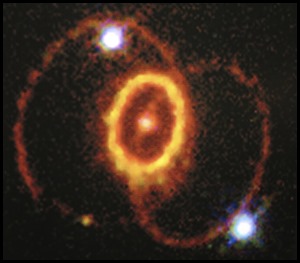

Supernova 1987A:

Supernovae are rare galactic events. When they happen, they can outshine an

entire galaxy. In 1987, New Zealand astronomer Albert Jones was one of the first

to see this supernova in a nearby galaxy, the Large Magellanic Cloud. At its

brightest, Supernova 1987A – 180,000 light years away

– was visible to the naked eye in the Southern Hemisphere.

The Universe, Everything and

Life: Somehow, out of the lifeless elements, life emerged on Earth. A

few billion years later we evolved: conscious creatures capable of finding out

about the Universe, and communicating with other forms of life out there – if

there are any.... For the meantime I have quite enough to get straight in my

head.

J.B.S. Haldane said “My own suspicion is

that the Universe is not only queerer than we suppose, but queerer than we can

suppose.

I feel no need to disagree with this

sentiment.

Neutron Stars: Neutron

stars are very small, extremely dense stars. A teaspoon or two of the stuff from

the inside of a neutron star would weigh about as much as all six billion people

on our planet put together. As their name suggests, neutron stars are made

almost entirely of neutrons – subatomic particles with no electrical charge.

Neutrons can pack together much more densely then ordinary atoms, which have

positively charged protons and negatively charged electrons that push each other

apart. In fact, neutron stars are typically less than twelve kilometres across.

Neutron stars are formed when a star explodes in a supernova and leaves behind a

remnant with a mass somewhat greater than our Sun. If the remnant is more than

five times bigger, it will collapse even further to form a

black hole.

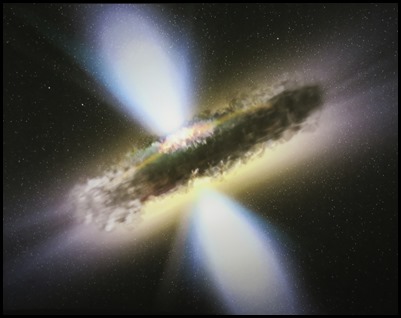

Monsters on the Edge of the

Observable Universe: Quasars are very distant galaxies that are among

the furthest objects astronomers have detected. Because quasars are so far away,

their light has been taken billions of years to get to us – which means they can

show us what galaxies were like when the Universe was young and violent. Every

quasar has a star-eating vortex at its centre – a supermassive black hole. The

black hole is surrounded by a huge whirlpool of half-digested stellar material,

and spits out a thin jet of highly-charged particles light years long.

Quasars were first detected by radio astronomy:’quasar’ is short for

quasi-stellar radio source. But quasars also produce enormous amounts of energy

in the form of x-rays, gamma rays and ultraviolet light. A single quasar can

produce a thousand times more energy than a galaxy like the Milky Way. In fact,

spiral galaxies like our own may be ex-quasars that have calmed down as they

reached middle age, with their stars forming stable orbits around a less active

black hole.

Black Holes: Black holes

are areas of space so dense that nothing that crosses the event horizon can

escape their gravitational pull: not stray astronauts, not massive stars – not

even light. Black holes are created when a huge amount of matter collapses under

its own weight – for example, when a giant star runs out of fuel and

self-destructs in a supernova. Supermassive black holes found at the centre of

galaxies like our own may be as massive as hundreds of billions of ordinary

stars. At the centre of a black hole, space and time may be infinitely curved by

gravity. If you’re ever unlucky enough to be sucked in to one, your final

moments will be spent being stretched out like a piece of string – instant

spaghettification, or Bears new word.

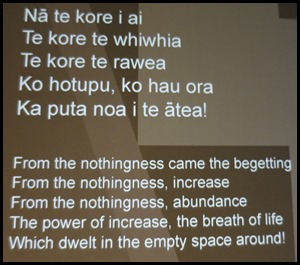

The Māori

Story

Knowledge: The Māori

creation story is based on observation and understanding of the Universe. This

ancient wisdom has many parallels with modern science: the seed of life at the

dawn of time, the separation of light from matter, and the ever-expanding

Universe.

Potential: In the

beginning, there was lo-matua-kore – the first, the parentless, not knowing but

always there. In lo was the potential for everything in the

Universe.

Becoming: Out of lo came

Te Kore, the void. Te Kore stirred and quickened, and the stars, Ngā Whetu, were

born. The stars brought forth darkness, Te Po, and light, Te Ao. Here, the

ancestral line divides. The long night gave birth to the earth mother,

Papatuānuku, and from the light, Ranginui the sky father emerged.

Atua: The children of

Rangi and Papa are atua, or gods – emanations of universal and physical life

forces. All things spring from them, including us. Atua – and we, their

descendants – are also Kaitaki, guardians of the natural world.

The Long Night: Rangi and

Papa held each other in such a close embrace that no light could come into the

world. Their children were suffocated by darkness.

The Separation: The atua

decided to free themselves by separating their parents. Tumatauenga began to

sever Rangi and Papa’s arms. But Tāne argued for a less cruel approach. He

braced his shoulders against his mother and pushed his parents apart with his

legs. For the first time, the children stood in the light – Te Ao

Mārama.

Our World: Most of the

atua stayed with their mother, Papa. Tanaroa is the ocean, Tāne the forest, and

Ruaumoko – Papa’s unborn child – earthquakes and volcanoes. But Tāwhirimātea,

the winds, followed his estranged father into the sky and plagued his brothers

and sisters with gales and storms. The atua created the world we live in, its

living creatures – and us.

Ritual of Retelling:

Every time the creation story is retold, the Universe is brought forth from the

void once more. There is no end to the story, because creation never stops

becoming. There is always a new generation waiting to add the next lines to the

story.

Whakapapa: For Moari,

cosmology is not only about explaining the Universe, but also about establishing

our place in it. That’s why it’s expressed in the form of whakapapa – genealogy.

There is no final distinction between people, the world that surrounds us, and

the Universe. Everything is related in an ancestry that stretches all the way

back to the parentless void, the origin of all things.

Te Moananui-a-Kiwa – the

Pacific Ocean, is the world’s greatest ocean, bigger than all the continents put

together. For most of our history, the islands scattered across it were unknown

and uninhabited, beyond the reach of humanity. But a few thousand years ago –

long before other seafaring cultures dared venture out of the shallows – the

ancestors of the Polynesian people set out an epic migration across the Pacific,

using the stars, the Sun and the Moon as guides.

The Natural World:

Polynesian navigation was based on a holistic

understanding of the natural world. Every voyaging waka carried a tohunga tātai

arorangi – an expert in astronomy and navigation. By observing the marine

environment – birds feeding offshore; migrating whales; tides, winds and ocean

swells; the Sun by day and the stars overhead by night – the tohunga guided the

waka from island to island. Whales migrate from

their summer breeding grounds in the Pacific to feed in the Antarctic over

winter. Some Māori tribes describe how their ancestors came to Aotearoa on the

back of a whale – perhaps voyaging waka followed their migration paths.

Fairy terns and noddies are sea-birds that fly

out to sea by day and return to land at night. Seeing these ‘navigator birds’

feeding at sea was a sign that land was near.When

a voyaging waka nears an island, the long ocean swells are disrupted by waves

bouncing off the land. Cloud patterns also indicate the presence of land that is

beyond the horizon. Aotearoa is “the long white cloud”.

Māui: The stories of Māui

– the great hero, trickster and demi-god – are known right across the Pacific.

Many of them contain ancient navigational insights and knowledge. Māui’s fishing

up of land is about the ancient discoveries of new islands below the horizon.

The story of the taming of the Sun may be about human understanding of the

movements of the Sun and stars – which could then be ‘harnessed’ to make

exploration and voyaging possible.

The Fishhook of Māui:

Māori legend tells how Māui used the sacred jawbone of Murirangawhenua, smeared

with his own blood, to fish up the North Island, Te Ika

a Māui – Māui’s fish. Māui’s fishhook, Te Matau a Māui – the tail of Scorpius,

is Aotearoa’s zenith constellation – at our latitude its highest point is

directly overhead. Red-glowing Rehua – Antares is said to be the blood Māui used

as bait.

Te Waka o Tamarereti: One

day, Tamarereti sailed far out on the ocean. Reaching land, the exhausted

navigator fell asleep, waking at dusk to light a fire for cooking. As he gazed

deep into the flames, Tamarereti remembered his loved ones back home and was

filled with a passion to return. Tamarereti gathered the brightly glowing stones

from the fire and scattered them in the sky to guide his journey home. The sky

father, Ranginui, was so delighted with Tamarereti’s work that he placed his vessel - waka, in the sky. The stars the ancestors used

to navigate to Aotearoa trace the shape of Tamarereti’s waka in the night sky.

In the winter sky just before dawn, it lies along the horizon, anchored to the

south.

The Navigators: The

people of the Pacific settled nearly every inhabitable island in the vast ocean,

from Hawai’i far to the north to Aotearoa here in the south. They reached and

returned from South America at the ocean’s easternmost edge. Their achievements

are all the more amazing because they were accomplished without maps or

instruments. Instead, the navigators of these voyages relied on an extraordinary

knowledge of the movements of the Sun and the night skies through the seasons –

memorised over a lifetime of training and observation – and on their heightened

senses, fine-tuned to the ever-changing environment of the ocean

world.

A Waka Renaissance: Much

of the knowledge of traditional navigational methods became incomplete or was

lost. But in some islands around the Pacific, the teachings were passed down

through the generations. In 1976, the Hokule’a – a twenty metre double hulled

canoe built by the Polynesian Voyaging Society – completed a return voyage from

Hawai’i to Tahiti under the guidance of Mua Piailug, a traditional navigator

from the Caroline Islands. The voyage of the Hokule’a was the beginning of a

waka renaissance, and a rediscovery of the ancient way-finding techniques.

Ben Finney described navigating aboard the

Hokule’a:- “Here we were sailing a double canoe across the dark ocean of the

third planet out from the Sun, steering on a succession of stars, one of which,

Alpha Centauri, is at 4.3 light years away – the closest star to our own – and a

moment later we were steering on a pair of external galaxies 179,000 and 210,000

light years away from us.”

ALL IN ALL FASCINATING, SOME

THINGS CLEARER, SOME MORE

WOOLLY |