Humayun's Tomb

|

Humayun's Tomb  We bimbled for ages from the car park, this site is massive. We passed the gate that would lead to Isa

Khan’s Tomb (own blog) and headed toward a white gate. Humayun’s Dream: It

had long been Humayun’s intention to found a great city, with lofty ramparts,

and a magnificent palace of seven stories, surrounded by delightful garden and

orchards.......This city should be the abode of wise and intelligent persons and

should be called Dinpanah. Khwand Amir, ‘Humayun

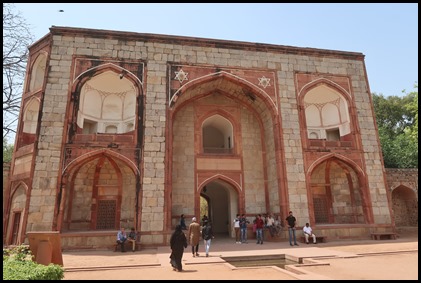

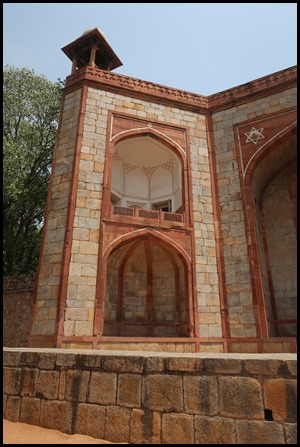

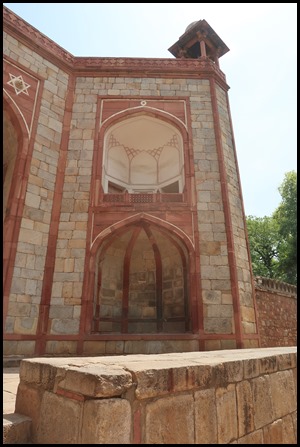

nama’.   Aligned in axis with the western gate of Humayun’s Tomb

enclosure and Subz burj, the 16th century gateway to Bu

Halima Garden Tomb stands on the eastern side of the enclosure. The upper

arched opening has sandstone jarokha with beautiful lattice parapet which is

supported on decorative sandstone brackets. Remains of the original tilework

decorations are still visible on the parapet. An anonymous saint known as

Bu Halima.   Then we passed Arab-ki-Sari, 1560 -

1561. The 48 foot high gateway (currently being renovated) served

as the southern entrance Arab Sarai – built to accommodate the Persian craftsmen

involved in the building of Humayun’s garden-tomb. The major part of the Arab

Sarai is today the Industrial Training Institute and not open to the

public.   The gardeners have their work cut out collecting millions of

fallen leaves. Then we went up to and through the

huge and imposing West Gate.    Now the main

entrance to the World Heritage Site of the Tomb-garden of Emperor

Humayan, this west gateway is sixteen metres in height. Rooms on each side

flank the central passage and the upper floor has small courtyards.

Six-sided

stars, used by the Mughals as an ornamental cosmic symbol adorn the structure.

Each side is crowned by a square chhatri composed of a jalied balustrade,

slender pillars, chajja and white marble cupola resting on a square inlaid

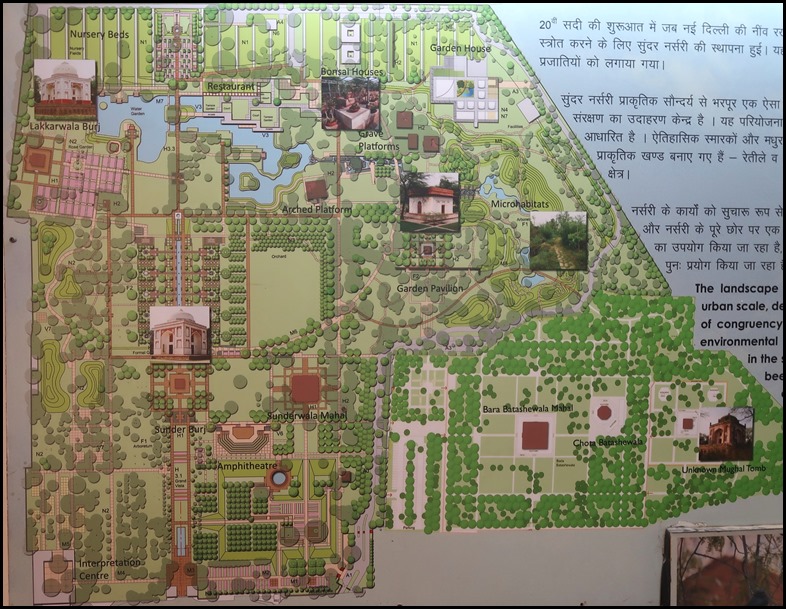

drum.  We entered a building that has been set up as an information

centre with fascinating snippets of history and this model

of the whole site.

Humayun inherited the Mughal dynasty when his father

Babur died in 1530. His reign got off to a good start, but his addiction to

luxury at the palaces at Agra left the door open for ambitious men to plot

behind his back. Ten years into his reign, Humayun was overthrown by the

opportunist Sher Shah, who took advantage of Afghan tribesmen to force Humayun

into exile in Iran, which was then ruled by the Safavid

dynasty.

Sher Shah died in 1545 and his successor was never able to assert the authority over the Afghani tribes that Sher Shah had enjoyed. As the remnants of the Shah's regime unravelled, Humayun mounted a restoration army and marched into Delhi in 1555. The aged Humayun had little time to celebrate, however, for barely six months later he died from a fall in his library at Sher Mandai. Humayun's tomb is believed to have been designed by his widow. Its plan, based on the description of Islamic paradise gardens, is known to have inspired the Taj Mahal and many later Mughal tombs. In 1857, the tomb was used as shelter by Bahadur Shah Zafar (son of Akbar II) and his three princes during the first war of Independence.

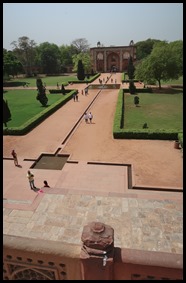

Time to read about this colossal garden. In Farsi, the term for ‘a walled garden’ is ‘pairi daeza’. In English the word became ‘paradise’ (heaven). Humayun’s Tomb is set in a walled garden. Arcaded walls enclose the 26-acre garden, which is divided by wide pathways into four quadrants. Narrower walkways, with water channels representing the rivers of the Quaranic paradise, further divide each quadrant into grids of eight squares, the ninth being occupied by the enormous tomb platform. Humayun’s Tomb-Garden is an example of a char bagh (in Persian, ‘char bagh’ means four gardens with four streams). This had its origin in the tomb of Cyrus the Great in Persia (6th century BCE). Later examples can be found in North Africa, Persia, Southern Europe, Central Asia and India. Babur, whose passion was flowering and fruit-bearing trees, laid out char bagh gardens, as did Akbar, Jahangir, and Shahjahan – in Agra, Kashmir, Lahore and Kabul. These gardens continued to inspire later ruler, particularly the Rajputs and the British. The char bagh gardens were for royal picnics, to receive dignitaries, for rulers to consult with ministers and as halting-places for the army when on the move. The low platforms at the intersection of the walkways would have been the base for tents, providing shade to visitors.

One of the small squares within a quadrant. A picture we took from the tomb’s plinth, the person looks diddy.

Plants in the Garden: The Mughal emperors meticulously recorded details of the gardens they created; Babur celebrated the birth of Humayun at Bagh-e-wafa, the garden he laid our near Kabul. He wrote ”it was a time of beauty, ... the fruit on the pomegranate trees bright red, and the orange trees green and fresh...” Mango and neem were planted along the enclosure wall, flowering hibiscus is planted in clusters at the termination of pathways along the walls, and groves of pomegranate were planted on the eastern side of the garden. Water in the Garden: Lifted from the Yamuna that flowed along the eastern wall, and from wells on the northern and western side – was carried over patterned water-chutes, filled the channels and irrigated the gardens. Terracotta pipes fed the fountains in the four central pools.

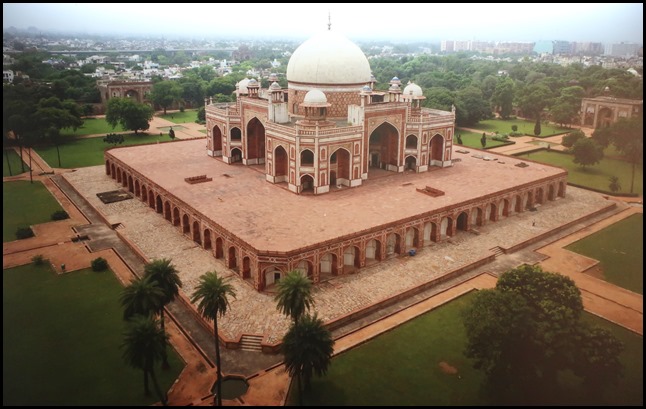

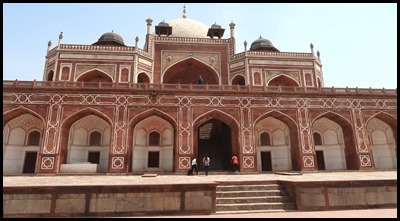

A picture in the display. Humayun’s Tomb stands 50 m tall, with the finial itself 6 m high. The mausoleum stands on 4,000 sq. m. The architect, Sayyid Muhammad Ghiyas chose to design arches of different sizes and repeated recesses to bring the building to human scale. The geometry in the architecture reveals that the various elements form a harmonious transition from the base platform to the bulbous external dome. The dome, monumental yet graceful, provides the building the crucial imposing scale. In India the Mughals used red sandstone, the

colour of the royal tent, for their buildings. The red-white contrast (used in

Delhi earlier by the Khalji and Tughlaq rulers) was significant to the design

and used with skill. The gleaming white marble dome crowns the facade of the

principal structure. This is built on a large plinth with 17 white

lime-plastered arches on each facade, framed in red sandstone inlaid with white

marble, “the whole breathing true Mughal splendour in its perfect

planning.”   After a really interesting time in the

display we headed toward the tomb. Time for pose

shots. Humayun died in 1556 AD following a fall in his

library. He was laid to rest at his palace at Purana Quilla in Delhi. Following

his death, Delhi was attacked by Hemu, the Hindu general and Chief Minister of

Adil Shah Suri of Suri Dynasty. To preserve the sanctity of their Emperor’s

remains, the retreating Mughal army exhumed Humayun’s remains and took them to

be reburied at Kalanaur in Punjab. Following her husband’s death, the grieving queen

Bega Begum set out for Mecca to undertake the Hajj pilgrimage and vowed to build

a magnificent mausoleum in his memory. She employed the services of a Persian

architect, Mirak Mirza Ghiyas, hailing from Herat region of Afghanistan and

having an impressive repertoire. Bega Begum not only commissioned and paid for

the construction of the tomb, but supervised its construction as

well.   One of the water features and

nearing the tomb.

The splendid mausoleum built in the memory of Emperor Humayun, the second Mughal ruler to ascend the throne, stands as a magnificent testament to the style of Mughal royal mausoleums. It is the first of the grand dynastic garden-tombs commissioned in. The tomb was commissioned by Bega Begum, Humayun’s Persian wife and chief consort in 1565 AD, nine years after the Emperor’s death. It was completed in 1572 AD under the patronage of the Mughal Emperor Akbar, the third Mughal ruler and Humayun’s son. Located in Nizamuddin, East Delhi, Humayun’s tomb or Makbara-e -Humayun is one of the best-preserved Mughal monuments and was declared a UNESCO World Heritage site in 1993. At the time of build the tomb cost £17,000 or 1,500,000 Rupees.

Looking back toward West Gate, the tomb now begins to take on ‘size’ and proportions.

The grandeur of this spectacular edifice gradually diminished due to lack of maintenance as funds dwindled in the royal treasury of the declining Mughal Empire. In 1880, after the establishment of the British rule in Delhi, the surrounding garden was redesigned to accommodate an English style garden. However, it was restored to the original style in a major restoration project between 1903 and 1909. The complex and its structures were heavily defiled when it was used to house the refugees during 1947 Partition of India. The most recent phase of restoration started in 1993, after Humayun’s tomb was named as a UNESCO world Heritage Site, by the Archaeological Survey of India (ASI) – Aga Khan Trust for Culture (AKTC).

We bimbled to a corner of the plinth and WOW, Huge, beautiful and stunning all at once.

The Humayun’s tomb is the starting point of the Mughal architecture in India. This style is a delightful amalgamation of the Persian, Turkish and Indian architectural influences. This genre was introduced during the reign of Akbar the Great and reached its peak during the reign of Shah Jahan, Akbar’s grandson and the fifth Mughal Emperor. Humayun’s tomb heralded the beginning of this new style in India, in both size and grandeur. The grand structure is situated in the centre of a 216,000 square metre garden complex on a raised 7-metre-high stone platform. The garden is a typical Persian Char Bagh layout, with four causeways radiating from the central building dividing the garden into four smaller segments. The causeways may also be adorned with water features. This Persian Timurid architectural landscaping style symbolizes the Garden of Paradise, which according to Quranic beliefs, consists of four rivers: one of water, one of milk, one of honey, and one of wine. The garden also houses trees serving a host of purposes like providing shade, producing fruits, flowers, and nurturing birds.Built primarily in red sandstone, the monument is a perfectly symmetrical structure, with white marble double domes capped with 6 m long brass finial ending in a crescent. The domes are 42.5 m high. Marble was also used in the lattice work, pietradura floors and eaves.

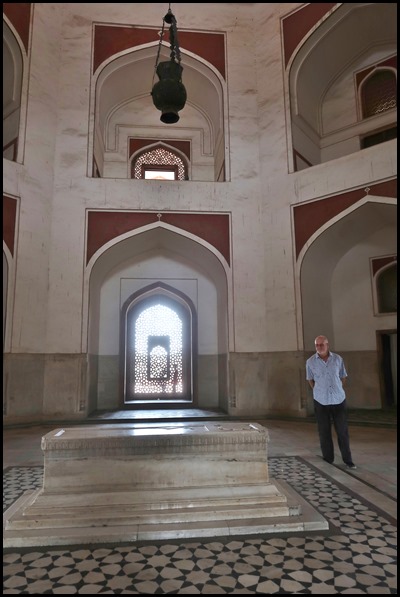

In the central burial chamber, a single cenotaph aligned on the north-south axis, as per Islamic tradition demarcates the grave of Humayun. The height of Humayun's Tomb is 47 metres, and its breadth is 91 metres. Two double storeyed arched gateways provide the entry to the tomb complex. A baradari and hammam are located in the centre of the eastern and northern walls respectively.

The main chamber has eight smaller chambers branching out from them. In all, the structure contains 124 vaulted chambers. Many of the smaller chambers contain cenotaphs of other Mughal royal family members and nobility. Humayun’s tomb is unusual for the numbers of other buried here, they include: Dara Shikoh, Shahjahan’s son, and later Mughal badshahs – Muhammad Azam Shah, Jahandar Shah, Farrukhsiyar, Rafi-ud-daulah, Rafi-ud-darajat, Ahmad Shah and Alamgir II.

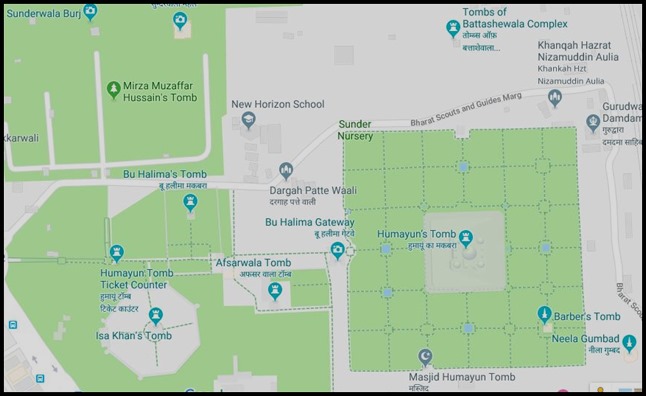

Bimbling around the mighty plinth we looked across to Lakharwala Gumbad, the tomb of an unknown person. Over the trees, Gurdwara Damdama Sahib (place of rest) was first built by Sardar Bhagel Singh in 1783, when a huge Sikh army under his command conquered Delhi. At first it was a small Gurdwara. Later Maharaja Ranjit Singh deputed his officials to renovate it. Consequently, a deorhi was constructed. Besides, some other buildings for priests and pilgrims were also added. In 1984 a new building was constructed. Every year thousands of devotees assemble here to celebrate the festival called Hola Mohalla.

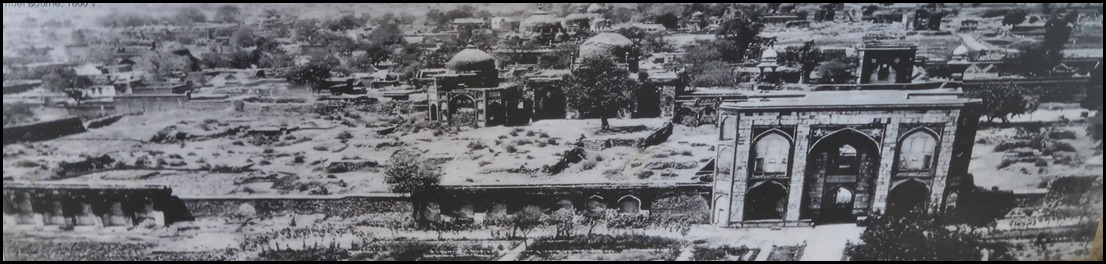

Samuel Bourne’s photograph taken in the 1860’s from where we are standing

today, showed what the ruins and tombs of Delhi looked like at that

time.

The

Humayun’s tomb complex comprises of several buildings, tombs, mosques, and a

lodging place. Important buildings in the complex are: Nila Guband, Arab Sarai

and Bu Halima. Tombs of Mughal royalty and nobility like Bega Begum, Hamida Banu

Begum, Isa Khan and Dara Shikoh are present within the main mausoleum building

and the whole complex is said to be dotted with over 160 tombs earning the

complex the name of “dormitory of the Mughals”.

The

tombs and buildings are centred around the shrine of 14th century Sufi Saint

Hazrat Nizamuddin Auliya, located just outside the complex. The Mughals

considered it an auspicious site to be buried near a saint’s grave, and thus

generations of Mughal royalty have chosen to be buried near the

site.

Barber’s Tomb and further round some of Humayun’s enclosure wall.

This Baradari was the first tomb to be built on the site in 1570, it has twelve doors (three on each side) for maximum ventilation.

We finished our circuit of the plinth taking in the seemingly (in some cases) placed tombs...............

...............took the steps and headed for the West Gate, not as impressive this side compared to entering from the other side.

Final words from Gulbadan Begum, Emperor Humayun’s sister:- There was in Humayun an innate gentleness, a trustfulness that was to naive, even for a child – a burnt child at least learns quickly to dread fire – but not Humayun: There was a quality of the saint in this strange man: Humayun never broke his promises.

ALL IN ALL MAGNIFICENT HUGE AND INTRICATE |