Big Canoe

Beez Neez now Chy Whella

Big Bear and Pepe Millard

Sun 25 Oct 2015 23:47

|

The Big Canoe on the Grass

Behind the Beach in Anelghowhat Bay

We saw this lady the first time we came ashore.

Today we asked about her.

She is/was a government sponsored initiative to

build and journey with sail and paddles to the Loyalty Islands, part of New

Caledonia. She was completed nine months ago and she was indeed test sailed

around the bay but with Cyclone Pam the project has been delayed, hopefully not

abandoned.

On our visit to the

Cultural Centre in Port Vila we read the following information.

The

revival of sailing. Since Independence in 1980, there has been a steady

revival and interest in the art of sailing in Vanuatu. In that year a group from

Atchin Island off north-east Malekula built the first large double-ender sail

canoe in almost a hundred years and sailed it to the Pacific Arts Festival being

held in Port Moresby, Papua New Guinea. In the early 1990’s, the Vanuatu

Fisheries Department started a program to re-introduce sailing to remote areas

in an effort to support the traditional canoe building skills found throughout

the country to assist with fisheries development of rural areas. With support

from that program, numerous communities in Vanuatu, from Aneityum Island in the

south to the Torres Islands of the north have revived

sailing.

In 1995 two

ten-metre canoes were sailed to Port Vila to commemorate the opening of the new

National Museum, one canoe from Maewo Island and the other from Atchin Island.

In 1998, a group from Aneityum sailed the ten-metre Dayspring IV to

Port Vila as part of the Presbyterian Church’s Golden Jubilee

Celebrations.

More

recently, the Vanuatu Cultural Centre has assisted in the revival of some of the

ancient traditional sail designs that had been lost for almost a hundred years.

In 1999, the community of Anelghowhat of Aneityum reconstructed from their

collective memory the oceanic lateen sail formerly used throughout most of the

southern islands. This reconstruction, woven entirely from pandanus leaves in

the traditional fashion, was on the canoe that took part in the Te Ngaru Matua

[The Ancient Wave] Oceanic Waka Festival held in New Zealand in March 2000. The

style of canoe cut for this event was also the style formerly found on Aneityum

and lost about thirty years ago.

The ‘wing tip’ or

oceanic spritsail of central and northern Vanuatu was also revived as part of

the Te Ngaru Matua event. This sail, unique to this part of the world was fitted

to a traditional canoe from Lelepa Island of north Efate and complemented the

canoe from Aneityum.

Canoes, both sail

and paddle, remain an important part of island life for transport, fishing,

trips to the garden and island travel throughout the archipelago. Its

contribution to Vanuatu’s cultural heritage, traditional and formal economy and

sense of self-reliance, identity and independence warrants further recognition

and support to ensure the skills and natural materials are maintained into the

future.

Bear looks

miniscule standing behind her and compared to what we

are used to seeing spuddling about the bay, she is massive.

Inter-island voyaging and trade canoes. Inter-island

trade depended on the large carved and planked outrigger canoes formerly found

throughout the islands. These were the ships of the past, fitted with sail and

having crews of up to thirty men. These canoes were considered sacred, as were

the trade voyages they went on. In some areas of Malekula, up to a hundred

tusked pigs would have been sacrificed by the time one of these inter-island

canoes was launched. In this way, the canoe was sanctified and empowered with a

name, a grade in the traditional hierarchy and a spirit to ensure successful

voyages. On the northeast of Malekula sanctifying rituals included the placement

of a stylised bird on the canoe ends to indicate its owners

rank.

Styles of inter-island canoes varied considerably

from one island to the next from north to south in the archipelago and reflected

the cultural diversity amongst islands. Generally, they were built up from a

carved log used as a keel with washboards [planks] sewn on to increase

freeboard. Various types of tree resins and techniques were drawn on to caulk

these sewn joints. The particulars of the canoe’s construction were often

specified by the areas ancestral cultural hero, as were the taboos associated

with its construction and use. In some areas a different language was spoken

while at sea.

The types of wood used to construct the hull varied

amongst the islands following the different trees preferred and available. Trees

commonly used included durable woods such as breadfruit, rosewood, ironwood or

softer, lighter woods like whitewood. A large sail canoe may include a dozen

different woods carefully chosen for each particular characteristic including

strength, flexibility, lightness and resistance to cracking, weathering and

insect attack.

Successful inter-island voyages also required

extensive local knowledge currents, tides, winds and weather prediction as well

as knowledge of the stars and other navigational

techniques.

Built solidly in the

traditional way.

Styles of Sails.

At the time of European contact, there were two main categories of sail found in

Vanuatu. The southern islands of TAFEA [Tanna, Aniwa, Futuna, Aneityum and

Erromango] used an oceanic lateen style of sail. This type of sail is considered

to have been refined by the Micronesians, adopted by the Polynesians and

introduced to southern Vanuatu some eight hundred years ago during the

Polynesian back-migration to the Western Pacific. This type of sail is shunted

[changed from end to end], which allows the outrigger to always face the wind as

opposed to the European method of tacking through the wind. It was lost fairly

early after European contact but it has been revived on Aneityum

Island.

A little fishing

canoe we see out and about every day.

The central and northern islands

of Vanuatu used a sail called the oceanic spritsail. A more descriptive name is

the ‘wing tip’, as it resembles the wings of a bird. Europeans called it the

‘butterfly’ sail when they first saw it. The ‘wing tip’ is unique to this part

of Vanuatu and is found nowhere else in the world. It survived until the early

1900’s when European sails displaced it. It resembles the extremely efficient

delta-foil shape utilised on high speed jets and is known to develop additional

power through creation of ‘vortex lift’.

The Shepherd Islands from north

Efate to southern Epi, being culturally distinct with evidence of other

Polynesian influences had their own variation of the oceanic spritsail, it being

more triangular in shape.

All of the larger inter-island

canoes were always sailed with the outrigger facing the wind. Its tendency to

fly in a strong wind was balanced by shifting cargo and crew weight out over the

outrigger itself. The sail rig of the oceanic spritsail could be changed to the

opposite end of the canoe, if necessary during a trip, but as most voyages were

less than a hundred miles, this wasn’t normally necessary. For the return trip

the mast would simply be shifted to its new position before departure. There was

always a strong tradition of weather specialists who foretold the weather by

reading winds and clouds as well as influencing the weather through ritualised

practices.

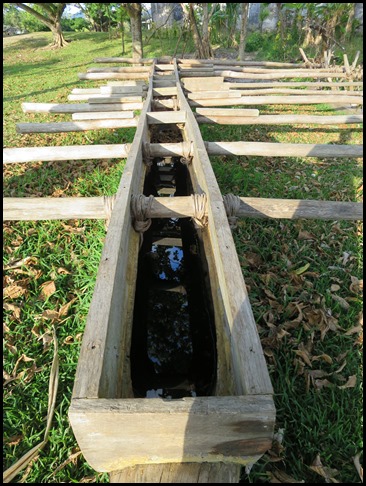

One of the support

beams.

Styles of sails in Vanuatu today. The types of sail

found today are all based on European styles that were introduced about a

hundred years ago. The European spritsail is the most common type of sail found

today. Areas where it is still used include Lamen Bay on Epi Island, the

Maskelyne Islands of southern Malekula and some islands in the Banks Group. This

style of sail was introduced in Aneityum in the 1990’s and has become popular.

Increasingly, some of these islands use a small triangular ‘leg of mutton’ sail

as well.

The small islands

of northeast Malekula, once a great centre of sailing and trade, now use a

European ‘balanced lug’ style of sail. This sail allows the outrigger to always

face the wind as was the case traditionally with central Vanuatu’s large ‘wing

tip’ rigged canoes. The introduced ‘balanced lug’ sail somewhat resembles the

oceanic lateen sail that was traditionally found in southern Vanuatu, but

differs in that the sail is not shunted when changing tack, but simply swung

around the mast.

In some

areas, coconut leaves are arranged on canoes as temporary sails to take

advantage of following winds.

Sad

to see one or two nails. All the

strapping would need to be replaced before this lady could set off.

The

demise of inter-island canoes and disruption of traditional trade. The

arrival of the Europeans had a drastic impact on traditional shipping and trade

in Vanuatu. Starting with the sandalwood trade around 1830, it became dangerous

to be caught offshore in a canoe. Canoes would be rammed and shattered so as to

capture the crew and cargo to be traded to their neighbouring enemies for

sandalwood. The ‘blackbirders’, in general an equally unscrupulous bunch, began

arriving in the 1860’s to recruit or sometimes enslave for Queensland and Fijian

sugarcane plantations. They would target the large canoes found offshore as a

source of easy ‘recruits’ by ramming them and hoisting the crews aboard their

ships bound for Queensland.

Many early

missionaries were intolerant of traditional practices and forbade canoe voyages

associated with traditional trade and rituals while finding their work easier if

the ‘natives’ were a little less mobile. The whalers, copra traders and planters

arrived in the mid to late 1800’s to alienate land, trade in firearms and

spirits and to introduce the European whaleboat with European style sails. They

also introduced disease, coupled with labour trade, severely depopulating many

islands. As the first Europeans always arrived by sea, their disruptive

influence was first felt in the coastal areas. The maritime skills of the old

canoe builders, sailors and navigators were one of the early victims of European

contact.

The outrigger is carved

from one tree trunk.

Some trees

would have to be taken out of her way to get her into the

water.

A

lick of varnish and a little TLC, we wish the lady safe

winds and a following sea.

ALL IN ALL QUITE A

VESSEL

A VERY SMART

LADY |