Collingwood Industry

|

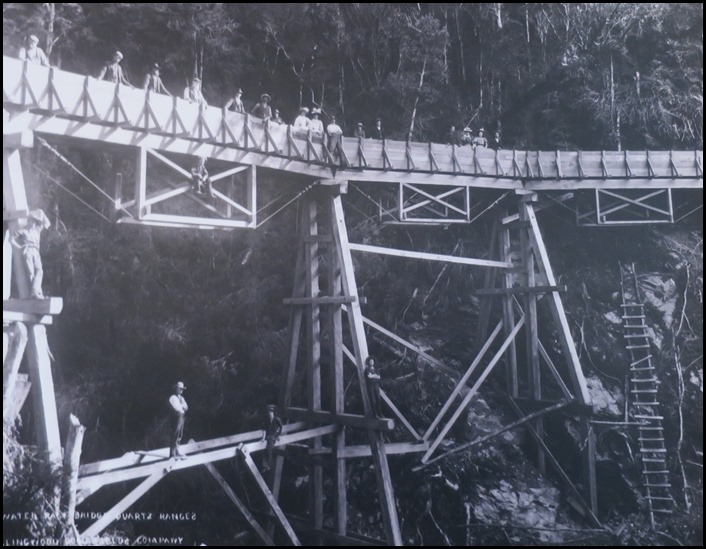

A Brief Look at the Past Industries of Collingwood

Flax: Aitia te wahine o te pa harakeke. ‘Marry the woman who is always at the flax bush, for she is an expert flax worker and an industrious person.’ From the earliest times to the present day, flax has been plentiful in Golden Bay. For Māori, harakeke was essential to daily life. The green outer layer was removed using a mussel shell which exposed the strong white fibre. This muka was spun into thread and woven into warm clothing or korowai – cloaks. Because of its strength it was used to make ropes, fishing lines and nets. The unprocessed leaf was used to weave baskets, food baskets and mats for flooring. The gum healed wounds and boiled roots made a disinfectant. Early Europeans were trading flax for export to America, Britain, Canada and Australia. Around 1860, a shredder was introduced. This stripped the outer layer from the leaves which were then fed between a revolving metal drum and fixed metal bar, washed then put through a ‘scrutcher’ made of wood. Finally, the fibre was laid out in the open to dry before being baled, transported to wharves and exported. By the 1840’s several flax mills operated between Collingwood / Aorere and Paturau, including Robert Strange at Ferntown, Daniell & Barnham at Pakawau, William Scrimgeour at Kaihoka and Hec Shaw, Jim Flowers and Frank Sharlond, at White Pine Creek, Rakopi.

Prouse & Saunders Tram Line circa 1906. Percy Prouse leaning in front wearing white braces, Jack England at rear with whip.

In 1903, Prouse & Saunders was established at Karaka Point, Paturau, with equipment they brought from Levin, North Island. This included two feet six inch gauge tram rails and honeysuckle timber sleepers adapted for both flax and timber milling. While providing employment for Māori and European, the industry also cleared land which became pasture for farming. However, World War One, followed by the depression years saw the final collapse of flax export markets. In the 1940’s, the last local flax mill produced woolpacks under government contract. This was operated by Hec Donelly at Pakawau with flax cut at Wharariki.

Timber: Because the river flats of the Aorere & Kaituna valleys were heavily covered with rimu, matai, miro, totara and kahikatea it was natural that sawmilling should become a thriving industry creating employment and trade in the district. From the mid 1800’s several saw mills were in operation from Takaka to Mangarakau. Many were set up in and around the Aorere Valley including Bainham, Rockville, Kaituna, Mackays Pass and Ferntown. Before the powered machinery and motorised vehicles of today, the industry was considered the hardest of occupations imaginable. The massive native trees were felled by sawyers, one at either end of a crosscut saw using a pull and pull action. The felled logs were then pit-sawed into timber involving one man in a pit below the log pulling down on the cutting stroke and the sawyer on the top pulling up. Bullock teams of six, eight or more were used to drag the logs from the bush to the tramway skids. They were then transported on wooden railed tramlines. It was normal practice to site the tramline where there would be a slight downhill run to the sawmill. Horses then carted the empty “trucks” back. Without the need of a transport licence, wagoners who controlled the bullock teams could operate if trade was offering. Transporting timber from the bush to Collingwood was extremely difficult as roads were mostly muddy tracks. Production increased with the arrival of steam engines used to power the saws and winches. Timber was used locally for sheds, bridges, fencing new housing and repairs to buildings destroyed by flooding or fire. Improved machinery and road conditions meant logs could be easily hauled greater distances. Quicker easier access to Collingwood wharf meant timber could be shipped to waiting markets around the country for the growing building trade. Matai in particular was sought after for flooring in Canterbury. To avoid congestion at Collingwood wharf where large stacks had to be assembled awaiting shipment and ships required unloading space for incoming goods, each mill and other major traders had their own wharves.

Gold: In 1842 one of Arthur Wakefield’s party is reported to have found traces of gold in the bed of the Aorere River and in 1843 a New Zealand Company surveyor picked up a piece of gold there. These finds drew little attention. The eventual discovery of gold in the Aorere Valley remains subject to controversy. Credit is now given to Ned James and John Ellis for finding gold in 1856 and to George Lightband for developing the field. The gold rush brought prospectors into Golden Bay who were dispersed from the Aorere River to the Anatori River – from Collingwood to Takata. By March 1857 optimism was high and soon the goldfield population was estimated to be thirteen hundred, with another six hundred being Māori. Miners made the voyage to Golden Bay by boat, sometimes as stowaways on the Lady Barkly. From Gibbstown each miner carried his own swag. Later there were pack bullocks and then bullock carts. In winter 1858 the population declined to an estimated two hundred men due to constant bad weather. Many men returned home. In 1860, diggers remained on the Aorere Field; the Rocky River, Snow’s River, Appo’s Flat and Katuna were still popular. During 1862 gold was discovered at Te Taitapu by Māori owners who then instituted licence fees. At the end of the licence term one holder, Repo, assigned his claim to Tamati Pirimona Marino – buried in the Old Cemetery in Collingwood, and Wairi Raua. The 1890’s saw the formation of three of the largest gold mining concerns to operate in the Collingwood area: the Parapara Hydraulic Sluicing Company, the Collingwood Goldfields Company and the Taitapu Gold Estates Company. By the early 1900’s goldfield activity was winding down. Through the ensuing years, and during the depression, there was intermittent mining but never again has there been the intensity and activity of the nineteenth century.

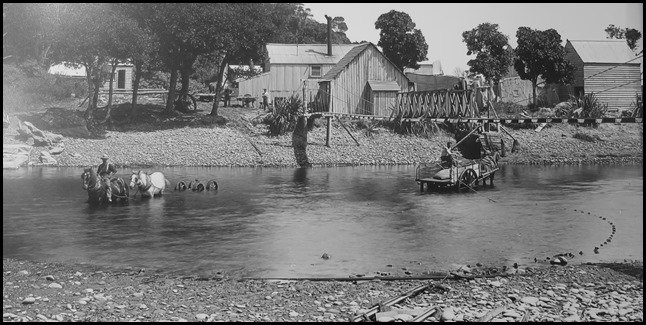

Mouth of Puponga

Mine.

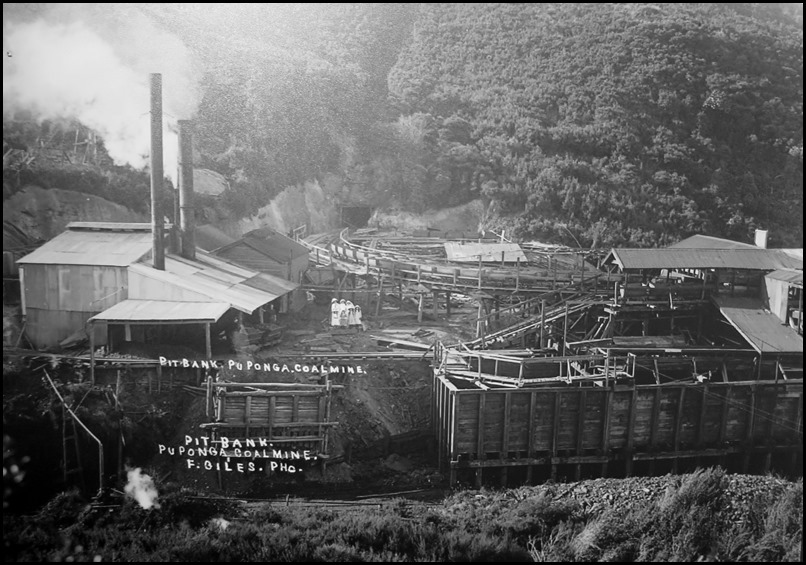

Coal: Coal forms as dead plant debris accumulates, primarily in swamps and forests, which when decayed and compressed deep down in the ground, becomes peat which then metamorphoses into coal. In North West Golden Bay coal mining operated from the early 1800’s until 1974 with at least ten mines operating at varying times:- The Collingwood Mine – also known as Wallsend & Ferntown, Mount Burnett, Pakawau, Puponga – the last mine to close, North Cape, Wharariki, Whanganui, Westhaven Mangarakau and Oyster Point, all of which were horizontal shaft mines where miners went down the dip to the coal-face. In early days miners worked the coal face with picks and shovels; explosives came later along with hydraulic and hydro methods. Coal was then ‘banjo shovelled’ – a short handled shovel with a broad ‘scoop’ into wagons, pit ponies drew the wagons to the bottom of the dip; wagons were winched from there up to the bins, taken to the wharf by steam locomotive and the coal was loaded via chutes onto boats.

A surcharge applied to road transport; two pennies per ton per mile Pakawau to Puponga and Whariki, and Pakawau to Paturau and Anatori. In 1938 the Collingwood Harbour Board was charging three pennies per ton on coal shipped over the Collingwood wharf. In the 1950’s locals were buying Mangarakau coal for two pounds per ton for domestic fires. Other Golden Bay users included the Collingwood Maternity Hospital, Dairy Factories and Golden Bay Cement Company. Fatal accidents at the Puponga mine occurred in 1905 and 1967, each time resulting in the loss of one life. The 1958 explosion at Mangarakau mine took four lives and injured one person. In mines known to be gaseous, budgies or canaries were used as early warning systems as they, being small, detected gas long before the miners did. When rescue attempts were made at Mangarakau a budgie was carried as a test of air but when the bird was affected the rescue party withdrew.

Puponga Coal Company’s Wharf, Collingwood.

ALL IN ALL EVER CHANGING AND HARD WORKING USING WHAT’S THERE, NOW ALL GONE |