Platypus House

Beez Neez now Chy Whella

Big Bear and Pepe Millard

Wed 20 Jan 2016 23:37

|

Platypus House

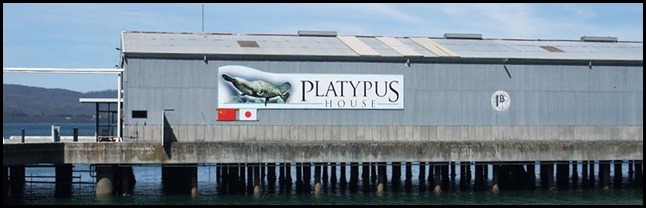

We left

Beaconsfield Mine and headed to Beauty Point, a quick bite to eat in Mabel and

then we took the short walk from the car park to the converted warehouses on the

pier that are now home to Platypus House on the right and Seahorse World next door,

on the left. We had time to look around the Education Room before Tracy, our

guide took us in to see our first platypuses.

Wow. We walked into a darkened room and

saw three tanks. In the first was Jupiter, about

eight years old and current beau of Dawn. He weighs three kilograms and is

described as big bodied with bright eyes. His favourite food is fat earth worms,

his favourite pastime is showing off and wagging his tail. We watched as he swam

up and down his tank, miss a couple of yabbies bimbling about of the floor of

his tank, hold his breath and scruff under the pieces of wood and eventually

walk up his plank to go to his day bed which also connects to the mating pool

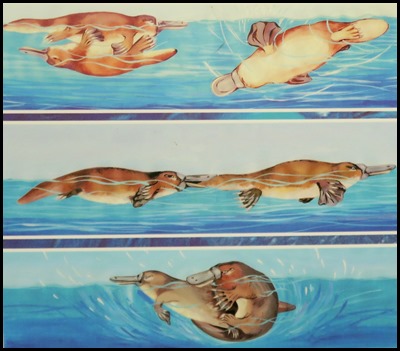

‘out back’. We were transfixed. Platypuses swim only using their front feet –

his rear ones just dangled and occasionally steered, his tail looked like a

course brush and his beak looked like badly shaped play-doh shoved on

willy-nilly.

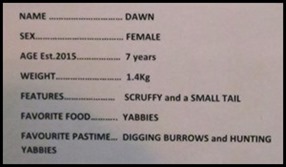

In the next tank was Dawn, sound asleep. These creatures can take a deep breath

and go underwater for about ten minutes, slowing their heart rate as they

settle. Eyes closed they look so strange. We both thought they would be bigger,

this just added to their cuteness.

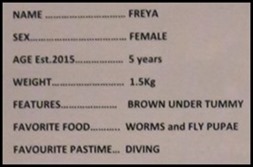

In the third and final tank was Freya, also fast asleep but constantly being bumped into by

Poppy. The girls, like Jupiter can access their day bunk or go through to the

breeding tank, should they fancy.

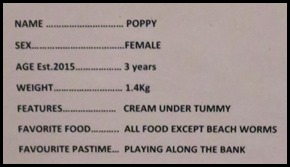

The vitals of the

girls.

Time to move on, in the next room we could

see the wooden tunnels at the backs of the tanks. The

Platypuses can bimble through, or stop for a nap in their day boxes. This end is

Jupiter’s, the far end is the girls.

In the farthest room was the breeding tank. No one popped in during our visit but it

looked very nice.

Tracy showed us the size of their eggs – about the size of a Mint Imperial and their

various snacks of earth worm, maggots and other tasty

titbits. When we returned to the tank room Jupiter was off

up his slope, sadly, the camera focussed on the water drops but it’s in

to give an idea.

A final look at the girls gave us a chance

to look up close to Dawn’s tail, where Platypuses store their fat. In the information room we would

get to feel just how course the tail is and how sharp the claws are, ideally

built for swimming and scruffing about.

As the animal dives a trail of bubbles follows as the air works its way through

their thick fur.

The platypus is Australia’s only aquatic

freshwater mammal, apart from the water rat, Hydromys chrysogater.

Platypuses are found in eastern Australia including all of Tasmania and King

Island. Their most northerly distribution is round Cooktown in Queensland and

west to Renmark in South Australia. Their

habitats are banks of streams and lakes: the animal feeding in the water for the

most part. In the winter they do not hibernate and will swim under ice to find

food; having air holes in the ice so they can pop up to take in a breath. Their

nostrils are slightly raised so the animal can obtain oxygen while the rest of

the body remains under water.

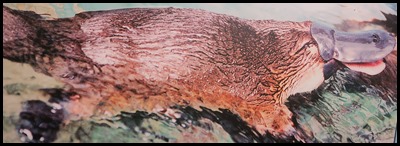

The nose end is

just a comedy. The bill is rubbery and leathery at the same time, and is not

‘fitted’ at the front edges.

Sadly, it was time to leave these amazing

little creatures to visit with the Echidnas. They were of course completely

unbothered and slept through our

leaving.

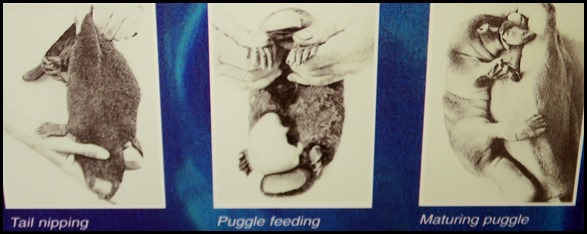

After our equally

fascinating look up close and personal with three friendly Echidnas we went back

to read the information and then to watch a video about a couple of researchers

who managed to get a fibre-optic camera into a nest to watch the feeding and

development of a couple of puggles.

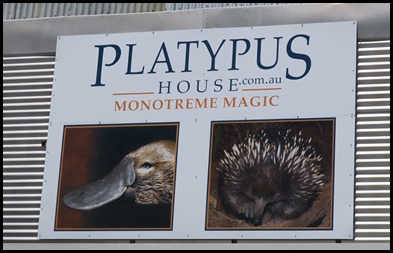

Platypus House was founded in 2002 by

Professor Nigel Forteath and Nick Jones. There are

only three Monotremes or egg-laying mammals in the world, namely the Platypus

and the short and long beaked Echidnas. The Platypus and short beaked Echidna

are found only in Australia.

Platypus House was built as an

educational experience to enhance public awareness of these unique and shy

animals. It is hoped that through public awareness and a better understanding of

the animals that we will see the urgency in wanting to save their environment

and in turn the species themselves. Australia is the driest continent in the

world and the consequences of ‘climate change’ on these unique creatures may be

dire.

Early climate change probably was

responsible for the extinction of Platypuses in Western Australia and the

Northern Territory. Platypuses were hunted to extinction in South Australia in

the last century and Tasmanian Platypuses have and continue to be threatened by

a fungal disease, Mucor amphibiorum, which has been responsible for a great many

mortalities.

In 2004 Professor Forteath was largely

instrumental in obtaining a significant grant for a major survey of the

Platypuses of Tasmania aimed at monitoring the spread of Mucor amphibiorum in

Platypuses throughout Tasmania.

Dr Tom Grant, in his excellent book on

Platypuses, lists several other very real threat to Platypuses such as drought,

organic pollution, salinity, introduced predators, introduced species [such as

frogs carrying the deadly fungus M. amphibiorium into Tasmania], and the

construction of deep water dams. Every day wetlands in Australia are threatened

by human development and of course these ecosystems form essential habitats for

the aquatic Platypus. The loss of waterways, whether through drought or human

activities, not only threaten the Platypus directly through loss of breeding

sites but also result in the reduction of invertebrates which are the food

of these unique creatures.

Bushfires and lack of bush diversity

also affect the lives of Echidnas and Platypuses. The former kill and maim

Echidnas and destroy their food supplies; early season fires kill their young.

Mono-cultures of Eucalypts seldom provide the diversity of invertebrates

required in the diet of Echidnas and at the same time may significantly reduce

the number of aquatic invertebrates in creeks due to a lack of mixed detritus

falling into the water which in turn will affect Platypus

numbers.

Platypus House is one of the few

places in the world where patrons can see live platypuses and learn both about

their life history and the threats they face in Australia’s changing

environment. Few people know about the biology of the Platypus and Echidna and

Platypus House is committed to a truly educational experience.

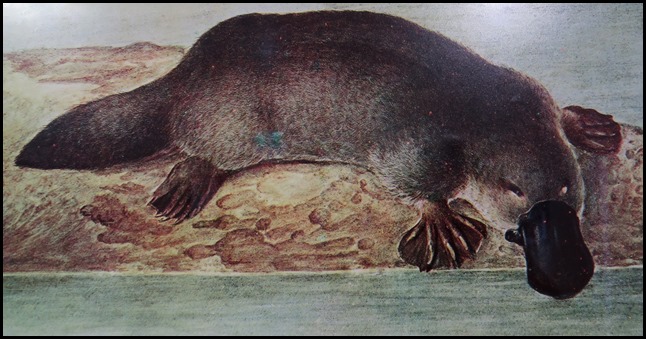

The Platypus, drawn by

J.W. Lewin in 1810. After the original watercolour in the Mitchell

Library, Sydney

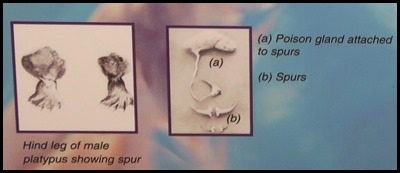

The monotremes are mammals that are

characterised by: laying eggs,

reptile-like front limbs [pectoral girdles] which extend outwards [laterally]; a

common urinary reproductive [urogenital] and rectal opening called a cloaca.

Cloaca comes from the Roman Goddess of Sewers viz: Cloacina; a penis that

carries spermatazoa only; unfused pelvic bones; a spur near the ankle in males

[with a poison gland in male platypuses]; mammary glands but no nipples, paired

ovaries [but only left ovary functional in platypus] undescended testes and no

whiskers [vibrissae].

There are two families of monotremes

left in the world namely the Ornithorhynchidae [platypus] – birdlike

snout and Tachyglossidae [echidna]. There is only one species of platypus

[Ornithorhynchus anatinus – duck like] but two species of echidna – the

Australian short-beaked echidna and the Guinean long-beaked

echidna.

It should be noted that Tasmanian

platypuses may be distinguished from those on the mainland and King Island by

differences in DNA.

Fossil remains of monotremes: opalised

jaw bone in Lightning Ridge N.S.W. - 150 million years old. Bone fragments in

lake beds in Queensland - 15 million years old. Skull, Riversleigh in Queensland

– 15 million years old. Tooth in Patagonia – 62 million years old.

Monotremes may well have lived

throughout the great land mass called Gondwanaland.

Platypuses feed during the day in the

colder months in Tasmania but during the summer, the evenings and early mornings

are favoured. It is not unusual for foraging to last up to 12 hours a day. It is

often said that platypuses eat up to half their body weight each day. This may

be true following periods of reduced food supplies e.g. flood, mass emergence of

aquatic insects, but well fed animals thrive on 15% of their body weight per

day.

Babies have one premolar and two

molars on either side of their upper jaw and two molars on either side of the

lower jaw. Juveniles lose their teeth soon after leaving the nest. The teeth are

replaced by horny pads which are renewed since chewing wears them

down.

Platypuses use touch stimuli and

electrical fields to find their food. Underwater they close their eyes, ears and

nostrils. The bill and the frontal shield are covered in minute pits which open

into sensory organs. From these organs nerves transmit messages to the brain,

especially the cerebral cortex. Indeed the bill is the platypus’ main source of

information about the outside world. Many prey species give off enough

electricity to inform the platypus of their presence and encourage a feeding

response by the latter. Other prey items are found using tactile stimuli. Not

surprisingly, there is considerable overlap between the two means of

detection.

Chewing: Platypuses catch most of

their food on the lake or river bottom, sieving through the mud, sand and

gravel. Small food items are stored in cheek pouches and brought to the surface

where they are chewed and sifted. Large prey items such as yabbies take

considerable time to chew and grind and perhaps the strange ridged serrations on

the lower jaw help sort the mashed pieces of food or simply serve to grip the

food. Some biologists have suggested the pouches store grit to assist the

grinding process but this is not proven. Certainly food may be regurgitated or

ground several times. The tongue is rough and two tooth-like projections which

may further enhance the grinding process.

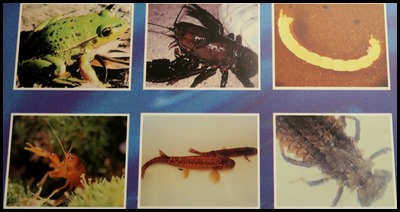

The food or diet of the platypuses

mainly consists of aquatic insect larvae / nymphs, aquatic worms and earthworms,

shrimps and yabbies, frogs and small fish. In

Tasmania salmonid eggs provide a welcome change to their diet. Tasmania is the

world’s hotspot of freshwater crayfish diversity. Many of our species are found

nowhere else on Earth, and some have very restricted distributions within

Tasmania.

The Cherax Destructor Yabby is a

native to most of mainland Australia but is an introduced species to Tasmania

and have infested some farm dams in the State. Yabbies can occur in a wide

variety of natural and artificial habitats including creeks, rivers, lakes, farm

dams and irrigation channels.

Cherax destructor has the potential to

carry disease and parasites harmful to our native crayfish and can degrade the

natural habitats of native species by destroying native aquatic vegetation and

increasing water turbidity. Their burrowing activity can also damage farm dam

walls and irrigation channels. The introduced yabby has been declared a

‘controlled fish’ Inland Fisheries Act [1995].

The Cherax destructor has a rapid

growth rate reaching maturity in as little as four months. Mature females devote

most of their energy into reproduction and can spawn prolifically up to three

times in a breeding season.

The yabbie has the ability to out

breed the Tasmanian yabbies and destroy the habitat for them and other native

species.

The Cherax destructor has been known

to completely take over small catchment areas causing turbidity and degradation

of their environment. Waters that have held strong populations of frogs,

tadpoles and aquatic insect and birds have become quite barren to anything else

other than the Cherax destructor yabby.....

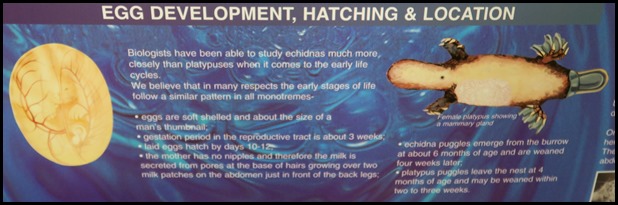

The platypus and the echidna are the

only surviving egg-laying mammals. The female platypus lays her eggs [one or

two] in a carefully constructed nest underground, while the echidna lay their

single egg into a crude, seasonally developed pouch. Once hatched, the babies –

known as puggles, feed on mother’s milk. The female platypus care for their

puggles in the burrow but the echidna only digs a burrow once the baby is too

prickly to carry.

Platypuses in the tropics tend to mate

in July but in Tasmania mating occurs in late September or October. Both types

of monotreme release a pungent odour during the mating season. Platypuses may

not mate every year and females probably do not mature until the age of five or

six years of age. Males mature at two years of age. Life expectancy can be

eighteen years.

Burrow temperatures are maintained

close to 18 degrees centigrade throughout the year. Platypuses are covered in

fur, in fact there are two layers of fur, the under fur is very fine and traps

an insulating layer of air. The flat bladed guard hair is longer and helps keep

the air bubble in place and aids insulation.

The hair on the tail is quite course

and probably plays no role in insulation. The fur dries very quickly out of

water. Moulting of the long guard hairs takes place in late

spring.

Platypuses like to keep their bodies

at about thirty two degrees Centigrade. They hate the heat and hide in their

burrows in hot weather.

The male platypus has a spur on both

ankles attached to a small bone which articulates. When angry or threatened the

spur is moved at right angles to the leg and is ready to be kicked into its

victim and venom is released. The venom is a cocktail of toxins, several of

which act directly on pain receptor cells. Platypus venom will kill other

platypuses, cats and dogs.

There is no anti-venom against

platypus poison and humans have experienced excruciating pain but it is not

lethal.

What makes Platypus venom unique ???

There are only two mammalian venoms known in the world. The effect it has on

humans is profound. Victim’s experience intense pain and immediate swelling of

the tissue around the spur wound. Swelling and prolonged pain normally lasts for

up to three months, sometimes longer. Neither morphine nor any other pain killer

has any effect on the pain. Anaesthetising the affected area will help but the

patient will still experience intense swelling and throbbing. Study of the

effects of platypus venom and why it is immune to pain killers may well lead to

a better understanding of how human pain signalling works.

Both male and female growl when

threatened, however females communicate with their young in the nest by growl

sounds also.

In 1799 the British Museum received its

first Platypus and didn’t really know what to say about it......Our first

experience with the platypus – beak like a duck, fur bodied like a bear, bristly

tailed like a beaver, egg-laying like a bird, eats with grinding plates, can

reduce heart rate and produce venom like a snake.......... too amazing not to

protect. Time for happy pictures.

ALL IN ALL SUCH A UNIQUE

CREATURE

THE WEIRDEST ANIMAL BUT SO VERY

CUTE |