Pepe Back to 1969

|

Stepping Back to 1969 – will it have the same effect, will it

feel the same ???

History: I went on a school trip in

1969 to Bethnal Green Museum. There I saw a painting, kept going back to it, was

absorbed by it, fascinated by it, moved by it and totally captivated by it. I

bought a postcard of it and have stared at it so often over the years. In these

modern times I have a print of it on my laptop as to easily take a peek at it.

In many ways I am exposing a bit of myself by letting you in on this but as you

have been with us so long - here goes.

To this day I have never been so

moved by any painting since. Maybe, my dear blog reader you have experienced

this feeling, maybe not. I personally don’t understand how anyone can feel or be

moved by modern art but I have to respect that it can. Some will be surprised

that a person who loves colour and vibrancy can feel emotional at something so

dark, dismal and sombre.........

Since: Any time as a family member I

have come to London we have always driven straight to relatives. My mum would

never come ‘in to town’. The first time I came shopping was in 1975 and that was

to Petticoat Lane Market. In 1981 I went to Bermondsey Market to buy my silver

nurses buckle. In later years I have been up on conference, to see shows and to

bring Bear to see the Lion King and stay at Brown’s Hotel for his fiftieth

birthday trip. Never fitted in any sightseeing or museums.

Today: The whole point of our week in

London was to ‘do’ the tourist stuff we have never done before. I didn’t feel I

could drag Bear and Harley to Bethnal Green, so I was absolutely thrilled when I

checked on line to find ‘my painting’ was now housed in the Victoria and Albert

Museum. So close to the centre of things that I would be able to factor in a

half an hour to marvel – alone to begin with. Over the last few days I have

looked at my print on my desktop and wondered whether I would break some sort of

spell by revisiting after all these years............It still moves me the same

way so it seemed worth the risk.

Well it happened today.

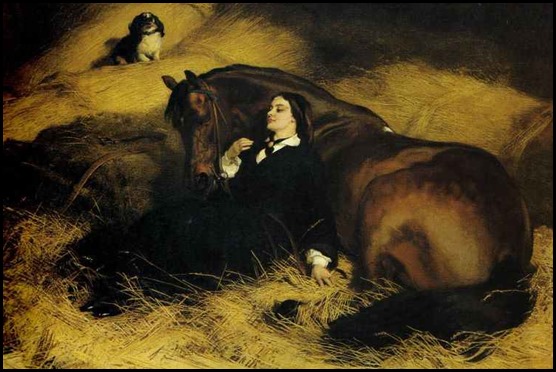

This is The Old Shepherd's Chief

Mourner that I have on my desktop.

It took ages to find it

as museum staff members kept sending me to the wrong gallery. Eventually,

I found Bear who went on the museums’ website and the young lady who had

suggested it waited while we searched, gave us a map and off I went on my own.

The boys would give me ten minutes and follow on. After I told my story to the

lady in the gallery itself, led me to it and said if I wanted to use flash “Well

you do whatever you need to do and let me know how it goes”. A lousy position

for light, reflection, position, height...................but the old feelings

were most certainly there.

Bear approached and I caught his

first moment. What do you think ??? A shame it is

so dark but it tells such a story, truly

beautiful.

Me with it. The only

physical difference between today and 1969 is that I don't remember it being so

small.

The boys

had been patient with me so it was only right for them to be in this most

personal blog. Harley indeed wanted to be part of it.

ALL IN ALL ASTOUNDING, THOSE

SAME OLD FEELINGS

WONDERFUL TO SEE AFTER HEARING SO MUCH ABOUT

IT

I have never carried on

after an all in all but want to feature in Sir Edwin Henry

Landseer‘s story.

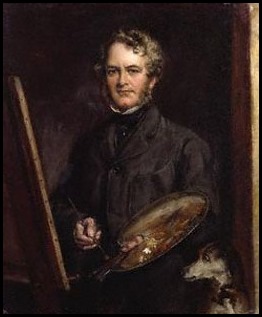

Wiki says: Sir Edwin Henry

Landseer RA (7th of

March 1802 to the 1st of October 1873) was an English

painter and sculptor,

well known for his paintings of

animals—particularly horses, dogs and stags.

However, his best-known works are the lion sculptures in Trafalgar

Square.

Life: Landseer was born in London, the son of the engraver John Landseer A.R.A. He was something of a prodigy whose artistic talents were recognised early on. He studied under several artists, including his father, and the history painter Benjamin Robert Haydon, who encouraged the young Landseer to perform dissections in order to fully understand animal musculature and skeletal structure. Landseer's life was entwined with the Royal Academy. At the age of just 13, in 1815, he exhibited works there. He was elected an Associate at the age of 24, and an Academician five years later in 1831. He was knighted in 1850, and although elected President in 1866 he declined the invitation. In his late 30’s Landseer suffered what is now believed to be a substantial nervous breakdown, and for the rest of his life was troubled by recurring bouts of melancholy, hypochondria, and depression, often aggravated by alcohol and drug use. In the last few years of his life Landseer's mental stability was problematic, and at the request of his family he was declared insane in July 1872. Paintings: Landseer was a notable figure in 19th-century British art, and his works can be found in Tate Britain, the Victoria and Albert Museum, Kenwood House and the Wallace Collection in London. He also collaborated with fellow painter Frederick Richard Lee. Landseer's popularity in Victorian Britain was considerable, and his reputation as an animal painter was unrivalled. Much of his fame—and his income—was generated by the publication of engravings of his work, many of them by his brother Thomas. His appeal crossed class boundaries: reproductions of his works were common in middle-class homes, while he was also popular with the aristocracy. Queen Victoria commissioned numerous pictures from the artist. Initially asked to paint various royal pets, he then moved on to portraits of ghillies and gamekeepers, Then, in the year before her marriage, the queen commissioned a portrait of herself, as a present for Prince Albert. He taught both Victoria and Albert to etch, and made portraits of Victoria's children as babies, usually in the company of a dog. He also made two portraits of Victoria and Albert dressed for costume balls, at which he was a guest himself. One of his last paintings was a life-size equestrian portrait of the Queen, shown at the Royal Academy in 1873, made from earlier sketches.

Landseer was particularly associated with Scotland, which he had first visited in 1824 and the Highlands in particular, which provided the subjects (both human and animal) for many of his important paintings. The paintings included his early successes The Hunting of Chevy Chase (1825–6), An Illicit Whisky Still in the Highlands (1826–9) and his more mature achievements, such as the majestic stag study Monarch of the Glen (1851) and Rent Day in the Wilderness (1855–68). In 1828, he was commissioned to produce illustrations for the Waverley Edition of Sir Walter Scott's novels. So popular and influential were Landseer's paintings of dogs in the service of humanity that the name Landseer came to be the official name for the variety of Newfoundland dog that, rather than being black or mostly black, features a mix of both black and white. It was this variety Landseer popularised in his paintings celebrating Newfoundlands as water rescue dogs, most notably Off to the Rescue (1827), A Distinguished Member of the Humane Society (1838), and Saved (1856). The paintings combine the Victorian conception of childhood with the appealing idea of noble animals devoted to humankind, a devotion indicated, in Saved, by the fact the dog has rescued the child without any apparent human involvement. Landseer's painting Laying Down The Law (1840) satirises the legal profession through anthropomorphism. It shows a group of dogs, with a poodle symbolising the Lord Chancellor.

The Shrew Tamed, was entered at the 1861 Royal Academy Exhibition and caused controversy because of its subject matter. It showed a powerful horse on its knees among straw in a stable, while a lovely young woman lies with her head pillowed on its flanks, lightly touching its head with her hand. The catalogue explained it as a portrait of a noted equestrienne, Ann Gilbert, applying the taming techniques of the famous 'horse whisperer' John Solomon Rarey. Critics were troubled by the depiction of a languorous woman dominating a powerful animal and some concluded Landseer was implying the famous courtesan Catherine Walters, then at the height of her fame. Walters was an excellent horsewoman and along with other "pretty horsebreakers", frequently appeared riding in Hyde Park. Some of Landseer's later works, such as his Flood in the Highlands and Man Proposes, God Disposes (both of 1864) are pessimistic in tone. The latter shows two polar bears toying with the bones of the dead and other remains, from Sir John Franklin's failed arctic expedition. The painting was purchased at auction by Thomas Holloway and hangs in the picture gallery of Royal Holloway, University of London. It is a college tradition to cover the painting with a union jack, when exams are held in the gallery, as there is a longstanding rumour that the painting drives people mad when they sit by it. In 1862 Landseer painted a portrait of Louisa Caroline Stewart-Mackenzie holding her daughter Maysie.

In 1858 the government commissioned Landseer to make four bronze lions for the base of Nelson's Column in Trafalgar Square, following the rejection of a set in stone by Thomas Milnes. Landseer accepted on condition that he would not have to start work for another nine months, and there was a further delay when he asked to be supplied with copies of casts of a real lion he knew were in the possession of the academy at Turin. The request proved complex, and the casts did not arrive until the summer of 1860. The lions were made at the Kensington studio of Carlo Marochetti, who also cast them. Work was slowed by Landseer's ill health, and his fractious relationship with Marochetti. The sculptures were installed in 1867.

Miscellaneous: Landseer was rumoured to be able to paint with both hands at the same time, for example, paint a horse's head with the right and its tail with the left, simultaneously. He was also known to be able to paint extremely quickly—when the mood struck him. He could also procrastinate, sometimes for years, over certain commissions. The architect Sir Edwin Landseer Lutyens was named after him and was his godson—Lutyens' father was a friend of Landseer.

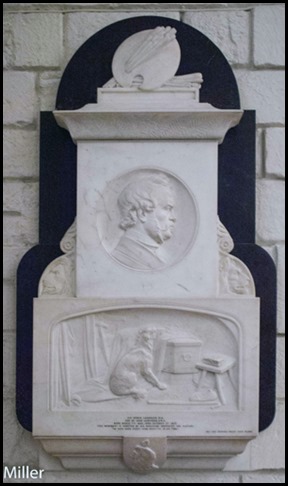

Death: Landseer's death on the 1st of October 1873 was widely marked in England: shops and houses lowered their blinds, flags flew at half mast, his bronze lions at the base of Nelson's column were hung with wreaths, and large crowds lined the streets to watch his funeral cortege pass. Landseer was buried in St Paul's Cathedral, London. His memorial is on the south wall – second recess by Woolner (1882). The relief at the lower part of his monument is based on his painting The Old Shepherd's Chief Mourner (much to my delight and how thrilling to stare at this on our visit to St Paul’s). At his death, Landseer left behind three unfinished paintings: Finding the Otter, Nell Gwynne and The Dead Buck, all on easels in his studio. It was his dying wish that his friend John Everett Millais (we walked past his house en route from our hotel to Kensington Park just the other day) should complete the paintings, and this he did.

Below is an article I found whilst writing this blog. Some of it I agree with, some of it I do feel and I was surprised to learn about March 1881 and the MSPCA.

MORE THAN A PAINTING: THE OLD SHEPHERD’S CHIEF MOURNER AND THE SEEDS OF EARLY ANIMAL ADVOCACY

By Keri Cronin — July 15, 2013

Whenever I am in London I make a trip over to the Victoria and Albert Museum (V&A) in South Kensington to see Sir Edwin Landseer’s 1837 painting, The Old Shepherd’s Chief Mourner. It is a funny thing, really, this need I have to go and stand in front of this painting time and time again. This is a painting I am very familiar with, one I’ve studied, taught, and read about many times. There are countless reproductions in books, online, and in print format. I know what to expect, in other words, and yet each time I stand in front of the image I am surprised by my reaction to it. This painting connects me to my work on the early history of visual culture in animal advocacy, and grounds me in a way that few other images do. The Old Shepherd’s Chief Mourner hangs in the darkened and crowded hallways of one of the British galleries at the V&A. It would be easy to miss if you were not looking for it. The protective glass of the painting’s frame actually makes it difficult to see the details in this image – I get a clearer view when I look at a reproduction on my computer. And yet, I don’t miss an opportunity to go and stand in front of it. John Ruskin, one of the most famous art critics of Landseer’s day, praised this painting, describing it as “one of the most perfect … pictures … which modern times have seen.” The gallery label accompanying this picture at the V&A tells viewers: This scene of the sentimental devotion of a dog won praise and popularity for its famous artist, Edwin Landseer. The animals he painted display human feelings and characteristics. One of the important aims of British art of the day was to illustrate sentiment and affection in paintings. While this accompanying label is factually accurate, it also omits a large portion of the story, namely that this painting became an important part of animal advocacy campaigns in the 19th century. For example, in March 1881, it was reproduced on the pages of Our Dumb Animals, the publication of the Massachusetts Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals (MSPCA), and declared to be “eminently appropriate” for this publication. The current gallery label points out that the animals Landseer painted “display human feelings and characteristics.” However, in the late 19th century, the MSPCA and other advocates took it a step further and saw this painting as an important way to underscore the fact that both human and non-human animals experienced similar emotions. In other words, this painting was not simply a visual symbol for human emotions and experiences. It was, at least for some viewers, a reminder of the shared experiences between human and non-human animals. This dog mourns the loss of a close companion, something many viewers of this painting would have experienced. Furthermore, this painting also highlights the strong emotional bonds that can exist between human and non-human animals. For an organization like the MSPCA, then, this kind of image was an important part of its advocacy efforts. The central figure in this painting is a dog who rests his head on the simple wooden coffin containing the body of his human companion, the “old shepherd” of the painting’s title. That this dog refuses to leave this man’s side – even after death – highlights the close relationship that these two had. Ruskin and others have pointed to the simple, rustic furnishings in the room where this scene takes place, underscoring the character of the man who once lived there. Again, this is all true – the bible on the stool points to piety, for example – however, it is the relationship between man and dog that became the focal point for so many viewers of this picture, including animal advocacy groups like the MSPCA. When I look at this painting, then, I can’t help but think of this history. It was a popular painting, and many prints were made of it during the 19th century. I often wonder about the reasons that would motivate people to purchase a print of this painting and hang it in their home. Undoubtedly the cachet of having a copy of a famous painting by a famous artist played a role here (similar to the way we might purchase a poster or postcard of our favorite works of art today); however, given the ways in which animal advocacy groups embraced this image, I think there was more to it than straightforward artistic adoration. When I look at The Old Shepherd’s Chief Mourner I feel strongly connected to the reformers and advocates from previous generations who understood the impact that art and visual culture could have in the very complex discussions about the ways in which non-human animals should be treated in our society, people who have paved the way for activists today. This painting and, indeed, most of Landseer’s other paintings are not taken that seriously by art historians and critics today. As the V&A gallery label indicates, this image is often read as an example of Victorian sentimentality, a throwback to “olden days” when life was somehow different from ours. However, it is important to take another look at this painting, to remember the place this image held in the minds of those involved with early animal advocacy campaigns. As is the case today, those wanting to change the world for animals relied heavily on visual imagery, and Landseer’s work was especially popular in this context. This image may have more in common with our current activist efforts than we recognize at first glance.

FOR THE FIRST AND ONLY TIME A SECONDARY ALL IN ALL WOW MOST EXTRAORDINARY |