Hartpury Churchyard

|

Hartpury Churchyard

Hartpury’s churchyard has always been lovingly cared for by the villagers and a maintenance fund existed by 1910. The annual costs – then only three pounds – were defrayed by subscription, sale of grass and “breaking of ground” fees. It was then rare to visit the churchyard without finding someone at work and tales are still told of cider and fruit cake provided by the churchwardens. Costs though, continued to rise and by 2004 amounted to one thousand six hundred pounds. The Parochial Church Council now strives meet the increasing gap between income and the costs of maintenance.

Seen at the bottom of the photo above is the signs to the Bee Shelter - our real reason for being here - that is until we got fascinated The churchyard is a haven for wildlife in a time of changing agricultural practice. Rare local varieties of fruit trees, particularly the perry pears, have been planted around the churchyard. Their blossom and fruit are already benefitting wildlife. Graves are regularly visited, but in some parts the mowing regime has been relaxed to allow the grass to grow benefitting insects and allowing wild flowers to set their seeds. A survey of the lichens in the churchyard has been carried out and their continuing wellbeing is to be monitored. Generally headstones and the lichen growth on them are left untouched, being part of the charm of the churchyard. Lichen are primitive organisms composed of an alga and a fungus living together. Some grow very slowly, only a half a millimeter a year and may be as old as the gravestone they are growing on. The sandstone memorial to Joseph Goodwin has at least nine different species living and growing on it. If the gravestone had been limestone it would have just as many but from a different range of species. One collapsed stone however, has been reset so that the inscription is again visible and the oldest surviving lower lias headstone has been restored.

The

PCC has rescued and rebuilt three table tombs that were in a state of collapse

and, adopting a policy of timely but minimal intervention, has always conserved

the listed Sloper chest tomb. The work of the craftsmen who carved the ancient

headstones is one of the joys of a country churchyard, but the loss of

traditional skills has in recent years led to a monotonous flow of unimaginative

lettering carved on predecorated, mass produced stones. The use of local stone

has declined due to the comparative cheapness of imported stone. This has led to

the diocese prohibiting the use of marble and granite and severely restricting

the installation of figures of angels, crosses and kerbing.

The

2001 edition of The Churchyard Handbook is far more positive than its

predecessors in its encouragement of initiative in the commissioning of

memorials. It states “It must be admitted that efforts to avoid the restless and

discordant effect of inappropriately shaped and sized stones can result in

uniform rows of very similar headstones, lacking the character of earlier

memorials. There is much to be said for encouraging variety, as long as the

emphasis remains on quality”. It asked those responsible for churchyards to

welcome creative and individual designs. May

the memorial be worthy of the life it celebrates! Although

the idea of marking a grave with a headstone dated from the Celtic and Roman

period, in medieval times individual stones or monuments were rare. The move to

erect personal memorials began after the Restoration, when the developing middle

class of the yeoman farmer, lawyer, merchant and master craftsman felt the need

to commemorate their lives and achievements. The

headstone and a smaller footstone were placed at either end of the grave

although many footstones have been removed over the years to make the

maintenance of a churchyard easier. The earliest stones were usually quite

simple, carved on one side of a thick piece of stone with a sunken panel

containing the inscription. As well as headstones, flat horizontal or “ledgers”

are also found. The ledger was sometimes raised on brick or stone walls thus

becoming a chest or table tomb, with the memorial to one or more members of a

family often embellished with symbolic decoration carved on its sides.

Most of the early

tombstones here are either Cotswold limestone, grey pennant sandstone from the

Forest of Dean (often appearing green due to lichen growth), or Old Red

sandstone from the Herefordshire borders, but there is one early one (John

Fletcher 1710) of lower lias limestone “mudstone”. This probably came from the

local Hartpury quarries on Woolridge. Even though its condition was very poor,

the decision was taken to restore it as part of the village’s heritage. The

stone bears the inscription: “Death

in a very good old age did end my weary pilgrimage And was to me an ease

from paine and entrance into life againe” A very good old age

was also reached by the local millers son who died in 1931 aged one hundred. His

death is recorded on his elder sister’s stone, which carries the

inscription: “Whosoever will, let

him take the water of life freely” Whether or not the

humour was intended, he certainly took the waters literally when playing as a

toddler with his brother near the mill pond. They fell in and were only kept

afloat by the skirts young boys wore at that time. It is surprising how

many of the epitaphs found on 18th century graves appear again and

again with only minor variations all over the country. One source would have

been the travelling peddler who sold songs and verses suitable for any occasion.

At Hartpury the

ancestors seemed to take delight in reminding us of our mortality as well as the

records of suffering: Remember man that

thou must die As thou art now so

once was I As I am now so shalt thou be Prepare thyself to

follow me

1747 All men are mortall

all are born to die Death all conducts

into eternity. Farwel dear friends

don’t for ye love complain We part a while but

soon shall meet again

1766 All you that come our

grave to see Prepare yourselves to

follow we Repent in time no

gold can save Not youth or old age

from the grave

1797 All you that pass

this way alone Pray think how soon I

was gone Death does not always

warning give Therefore be careful

how you live

1803 I was so long with

pain oppressed Which wore my

strength away And made me long for

endless rest That never can

decay

1819 Physicians tried but

all in vain Till God at last did

think it best To ease my pain and

give me rest

1916 I wonder if they

would approve, I told you I was ill,

in this churchyard so inspiring us to be creative and

inspiring.

This unusual Grade II

listed stone chest tomb of lawyer Thomas Soper who

died in 1703. The reclining effigy is likely to be of his wife Joane who died in

1676, making it a very early example to be found outside (not in a church).

Although it is very worn, it is amazing that it has survived for so long, no

doubt due to the yew tree that now disturbs the foundations. The monument was

sensitively restored in 2003 by one of the country’s leading stonemasons Rory

Young. Headstones only

started to appear in the churchyard after the restoration of King Charles in

1660. The symbolism on them was as important as the lettering in a largely

illiterate community; the death’s head showing the body’s decay and the winged

cherub spiriting the soul to heaven.

One of the best known of Hartpury’s headstones records the death of John Hale, a blacksmith, who was crushed by a bell in 1692

of Newent Church.

Loe

here's interred the Muses Passive Friend;

It is always desperately sad to see the grave of a young person, especially taken tragically - but at least Juliet's is beautifully kept and the grass short

Again the graves of

Melanie, Luie and Emma are so very loved and well

tended. Beatrix Potter’s ‘Tailor of Gloucester’ was based on a real tailor John

Pritchard, who married Martha daughter of Evan and Eleanor Williams. Evan and

Eleanor lie in this churchyard.

The cross only became a common feature in English churchyards during the Victorian era. Before it was regarded as ‘popish’.

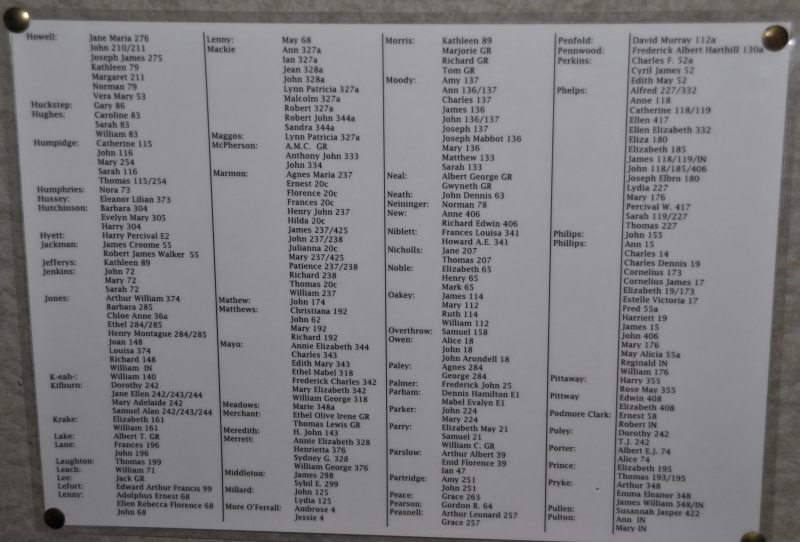

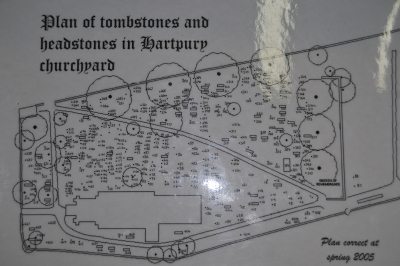

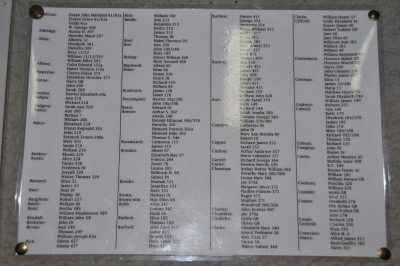

In the church porch was an excellent plan of the churchyard (and a booklet we bought) with lists of people buried here

Even two Millard's are here - John and Lydia

ALL IN ALL A FASCINATING, WELL LOVED AND MAINTAINED PLACE OF PEACE VERY PRETTY AND VERY INTERESTING

|