Freycinet VC

Beez Neez now Chy Whella

Big Bear and Pepe Millard

Sun 17 Jan 2016 23:57

|

Freycinet Visitor’s

Centre

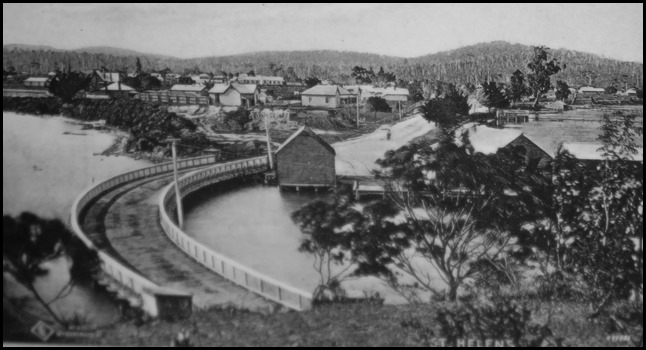

The Visitor

Centre.

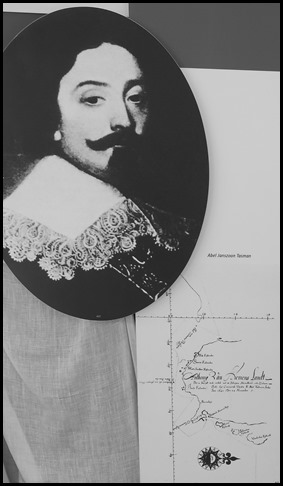

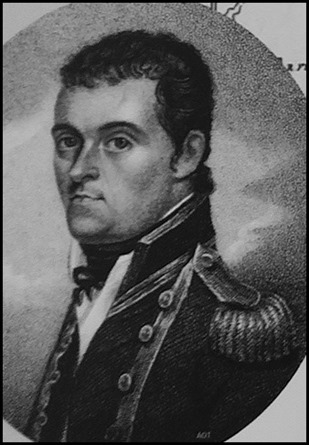

Abel Janszoon

Tasman and a page from his

journal.

No

sooner than we had entered the Visitor Centre - post Wineglass Lookout bimble,

[not far along the road from where we had parked Mabel], than we were at the

information boards.

When the first European explorers sailed along this coastline,

they gazed through telescopes at the land that was – to them – brand new. As

they charted the outlines of islands, bays and bluffs, they gave new names in

Old World languages – Dutch, French, English – to land that had already been named by Aboriginal people

for thousands of years.

The newcomers chose

names that acknowledged patrons and flattered politicians. Names that put a

personal stamp on their discoveries. Names that expressed their wonder or

surprise. But what they were doing here, so far from the European ports of

Rotterdam, Southampton and Le Havre ???

Dutch navigator Abel Tasman

commanded the first ships to sail into these waters. Europe’s seafaring powers –

the English, French, Portuguese and Dutch – were deeply curious about the

existence of an unknown southland that would balance the northern landmass of

the Old World. All wanted to be the first to find it.

In 1642, Tasman was sent by the

Governor of the East Indies, Anthony van Diemen, to explore for land in southern

waters and seek a new trading route to the Dutch colonies in south-east Asia,

avoiding the Spanish-held Philippines. Tasman’s route took him further south

than any European explorer had been. He sighted land to the west, skirted the

South Coast and was blown by heavy gales out of Storm Bay. Further north, he

named islands along the coast – one in honour of Governor van Diemen’s wife,

Maria, and another for a famous colleague and friend, Justus

Schouten.

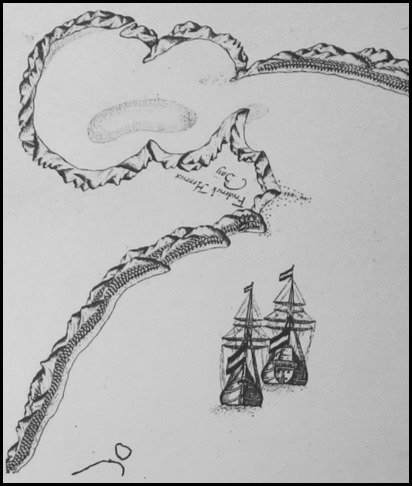

Tasman thought the peninsula we

know as Freycinet was an island, marking on his chart as Vanderlins Eylandt,

after Cornelius van der Lijn, who followed van Diemen as Governor of the East

Indies.

The East Coast waited 130 years

before its next European visit. This time, the French tricolour flew from the

masthead of Marion du Fresne’s two ships on their 1772 voyage of geographic

survey and scientific discovery.

Using information from Tasman’s

charts, they rounded Tasman Island and sailed north, dropping anchor south of

the Marion Bay Narrows and exploring ashore in search of fresh water and timber

for masts. Regrettably, his encounter with Tasmanian Aboriginal people resulted

in the first death from European musket fire.

In the following year, the

English arrived. Tobias Furneaux, captain of the ship

Adventure, was second in command to James Cook on their voyage to

explore deep into unknown southern waters. The ships were separated after

reaching New Zealand and Furneaux steered for Van Diemen’s Land, where he

sheltered in a bay he named for his ship. As he continued north along the

coast, Furneaux saw columns of smoke ashore - his chart marks the place as the

Bay of Fires.

[Furneaux was born in Swilly House, a

beautiful Georgian mansion with parts dating back to Tudor times, and set within

50 acres of rolling Devon pastures. It was described in a 19th-century guidebook

as 'agreeably situated in a sheltered lawn... set amongst well kept gardens and

pleasant sylvan surroundings'.]

On later

voyages, James Cook and William Bligh both landed in Adventure Bay, but the next British navigator to explore

the East Coast was John Henry Cox. In 1789 the brig Mercury anchored in the

western lee of Maria Island then passed north through the wide passage between

the island and the coast.

As the eighteenth century ended

in Europe, the quest for scientific knowledge grew. The adventurous French

navigator La Perouse was missing in southern waters on one of his bold voyages

of discovery, and in 1792 the French Government sent Admiral Bruni

D’Entrecasteaux to the far south, to search for La Perouse as well as to chart

unknown coastlines.

D’Entrecasteaux spent a month exploring the bays and

waterways of a wide channel separating Bruny Island from the mainland. His

ships’ boats rowed and sailed into the estuary of a wide river, Riviere du Nord.

[The Englishman John Hayes, followed the same route a year later in 1793,

renaming the river the Derwent].

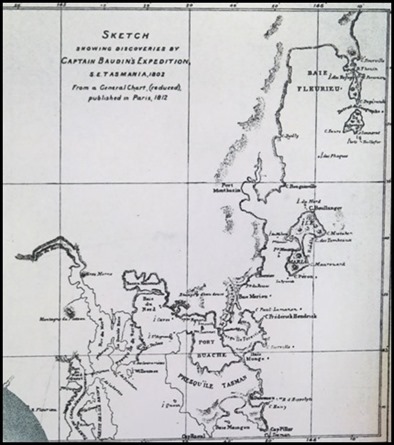

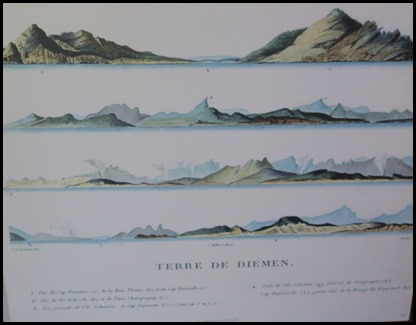

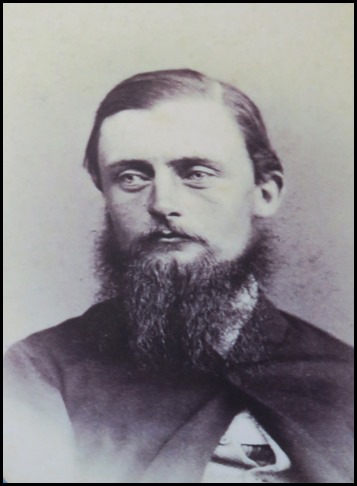

Sketch showing discoveries of Baudin’s expedition. Captain

Matthew Flinders.

At the turn of the

century, England and France were at war. While their armies and navies clashed

in European battles, the navigators of the world’s two great colonial powers

continued their voyages in distant oceans, gathering scientific knowledge and

filing away information of strategic importance.

In 1802, Admiral Baudin led a

French scientific expedition to explore the south coasts of New Holland and Van

Diemen’s Land. In the ships Naturaliste and Geographe, the

Frenchmen spent several weeks in the D’Entrecasteaux Channel and Derwent

regions, then made detailed surveys along the East Coast, making several

journeys ashore from anchorage near Maria Island.

Baudin’s cartographer Freycinet

explored inland and the expedition’s naturalist Francois Peron described and

classified 2500 new species of animals and plants and collected 100,000

specimens.

Sailing north to the Furneaux

Islands, the two ships became separated in a storm. The Naturaliste

surveyed the Hunter group and other Bass Strait Islands, then sailed north to

reach Port Jackson in April 1802. But Baudin in the Geographe passed

through the Bass Strait and continued into the Great Australian Bight, meeting

Matthew Flinders in Encounter Bay at the mouth of the Murray

River.

On the return voyage to Port

Jackson, for reasons unknown Baudin continued south down the west coast of Van

Diemen’s Land, completing his circumnavigation of the island. His crew was weak

with scurvy when they finally reached Port Jackson in June

1802.

Governor King received the French

visitors with hospitality and friendship, but he did not overlook the Empire’s

wider strategic interests – peace had been declared in Europe, but the world’s

political climate remained tense during the first years of the new

century.

Soon after Baudin’s two ships had

sailed from Port Jackson, King sent Lieutenant Charles Robbins to stake

England’s claim to the territory they had been exploring.

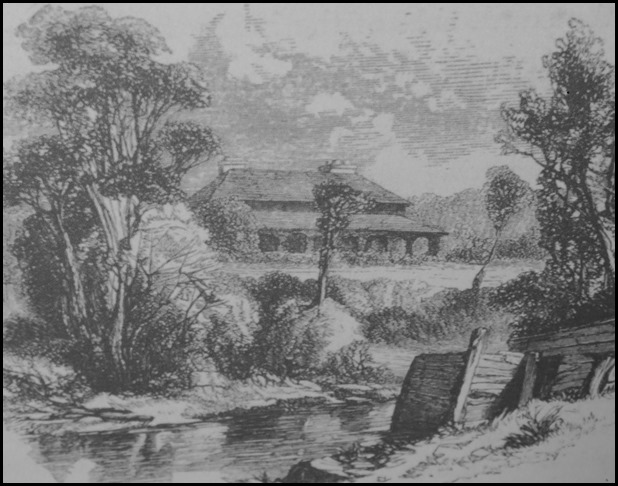

Claude-Francois Fortier’s

drawing

Robbins carried several sets of

orders – depending on the weather he may encounter, he was charged to raise the

flag at Frederick Henry Bay and the Derwent, or at King Island and Port Phillip.

To further establish the English claim, Robbins was instructed to place a guard

at each landing place, turn up the ground and plant seeds.

Robbins crossed paths with Baudin

on King Island, handing Baudin a brief letter from King, reinforcing the Crown’s

possession of Van Diemen’s Land and the southern coast of the mainland. An

English landing party planted the Union Jack under the noses of the amused

Frenchmen, who were studying insects at the time.

King then decided that even more

positive steps must be taken – in 1803 he ordered the youthful Lieutenant John

Bowen to establish a colony on the shores of the Derwent River, claiming all Van

Diemen’s Land for the Crown.

First, they came by sea

– then on horseback and on foot. Rough tracks became coach routes then motor

roads. Today’s comfortable drive of a couple of hours from Hobart or Launceston

to the East Coast was a multi-day expedition – not so very long

ago.

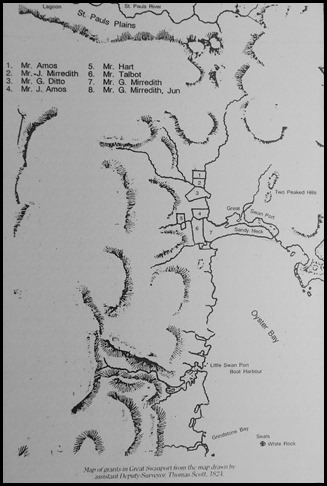

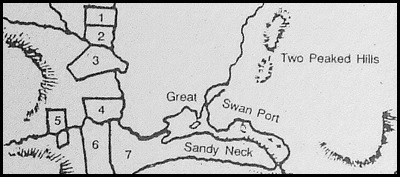

Two East

Coast families arrived in Van Dieman’s Land on the same ship - the Emerald, the

fist vessel to be privately chartered by free settlers, brought members of the

Amos and Meredith clans from England in 1821.

26th January

1816. “A heavy swell setting in from the Southard in the afternoon, we

hauled up in Waub’s Boat Harbour. Heavy surf on the beach half filled the boat

when landing, which wet our skins.” Bicheno entry in the James Kelly’s log

during his 1815-1816 circumnavigation in the whaleboat

‘Elizabeth’.

29th September

1821. “At daylight found we were in the bay off Little

Swan Port. Pulled at the oars for three hours and a favourable breeze springing

up, made Meredith’s Creek about ten o’clock where we found Mr. Amos had built a

small hut on the south side of the creek. Planted fruit

trees.”

30th September

1821. “Looked around for a convenient place to build a store to receive

and lodge our goods, implements etc.etc. and live in until the surveyor measures

off the grants and we can each fix a final residence and farm buildings,

stockyards etc. Caught fish.”

Diary of George

Meredith, first settler at Swansea.

The sheep here are large but

rather leggy. George Meredith in a letter to his brother John in

England.

George Meredith and Adam Amos

took their teenage sons with them when they left Hobart Town in an open

whaleboat for the voyage to the East Coast, where Lieutenant Governor Sorell had

sent them to choose their land grants.

George selected land at Meredith

River just north of where the township of Swansea would grow up. He built huts,

store sheds and stockyards, sowed wheat and barley and explored along the banks

of the Swan River seeking good grazing land for the livestock he’d brought from

England – not ‘large and leggy’ specimens like the local sheep but top-class

Saxon Merino rams and ewes.

Over the years, George Meredith

acquired thousands of acres of land, prospering from agriculture as well as

other activities including ship-building, flour milling and tanning. He also

pioneered shore-based whaling on the East Coast, operating stations at Coles

Bay, Refuge Island, Darlington and Prosser Bay.

There were bitter disputes about

land boundaries between Meredith and William Talbot, who had been issued an

identical authority to occupy the land. Governor Sorell finally granted Talbot

land in the Fingal Valley, where he established the fine grazing property

‘Malahide’.

The Meredith’s homestead was

designed and built by an ex-convict known as ‘Old Bull’. He built ‘Cambria’ to last, and it became the much-loved family home

for generations of Meredith’s, including the multi-talented Louisa Anne

Meredith, who had married George’s son Charles. Her evocative writings and

paintings captured the flavour of Tasmanian country life during the late 19th

century.

“Little

Walter died at four o’clock this morning. Robert very ill. Father and me making

a coffin.” Amos family diary entry 1842.

Adam Amos had

been a tenant farmer of George Meredith in Pembrokeshire, England. With his

brother John and their families, they joined the Merediths on a voyage of

emigration in 1821.

Adam chose land

on the middle reaches of the Swan River. His selection ‘Glen Gala’, was the

first of a collection of pioneer homesteads that formed the rural hamlet of

Cranbrook. The high

standards of farming established by the two brothers and their families

impressed the Land Commissioners, who rewarded them with extra grants of new

land to farm.

Amos became entangled in the feud

between George Meredith and William Talbot, but Governor Sorell attempted to

settle the matter by granting Talbot land in the Fingal Valley appointing Amos

to the position of Chief District Constable and Keeper of the

Pound.

Although they

were already skilled and practical people, the men and women pioneer families

faced the difficulties and dangers of establishing new farms in a new land. The

Amos family had its share of troubles – ‘Glen Gala’ was twice destroyed by fire,

and parts of its flour mill were swept away by floods. An Amos daughter drowned

in the mill race and a son lost his life in a riding accident.

But like other

East Coast Pioneer families, they persisted – and today, their descendants carry

on the traditions of hard work and care of the land.

“We visited a man who had become

notorious for the use of profane language and for cursing his eyes; he had

become nearly blind, but seemed far from having profited from his judgement.”

Quaker missionary James Backhouse after calling on John Harte.

A wild young man from a

distinguished Irish family, John de Courcy Harte settled in the district in

1821, building the homestead ‘Bellbrook’. Always in and out of debt, ‘Paddy’

Harte sold or leased part of ‘Bellbrook’ to Patrick Conolly and acquired some

poor quality land at Little Swanport in shady deals that led to legal strife in

years to come.

Paddy cooled his heels in the

Hobart Gaol for debt, went to New South Wales to seek new fortunes and finally

returned to reclaim ‘Bellbrook’ after fighting Conolly through the

courts.

The Surveyor-General JE Calder

never forgot his chance meeting with Harte in Radford’s Inn at Little Swanport,

during which Paddy managed to down two bottles of ale with his new friend, then

depart at a gallop without paying. Calder believed that Harte was

responsible for “many of the silly names

that disgrace our maps of the East

Coast” – the Paradise Gorge on the Prosser near Orford, Break Me Neck and Bust

Me Gall Hills were probably named by Paddy Harte.

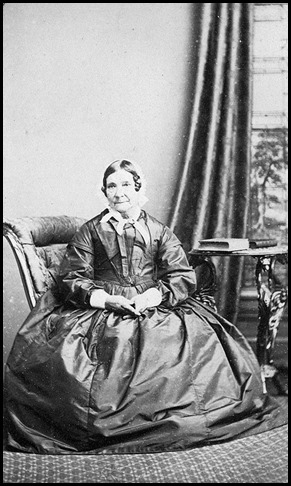

Francis and Anna

Cotton.

The Cottons of

Kelvedon. One of the East Coast’s most prominent pioneer families, the Cotton

dynasty began with Francis Cotton, who arrived in Van Diemen’s Land on 1829 with

his wife Anna and five children. Their close friend and fellow Quaker Dr George

Fordyce Story emigrated with them.

After losing many of their

possessions in a shipwreck on Maria Island and most of the rest in a fire at

their temporary cottage in Swansea, they selected land at Salty Lagoon south of

Swansea, built a house and established the estate they called ‘Kelvedon’ after

Anna’s home village in Essex. The house was the location of Tasmania’s first

Quaker meeting and there are two Quaker cemeteries on the

site.

Dr Story lived with the Cotton

family and worked from a surgery at ‘Kelvedon’. He once rescued Anna Cotton and

her youngest daughter Rachel from a drunken hold-up attempt by ‘Dido’, a

bushranger who had once worked as a labourer for the Cottons. “Oh Mrs Cotton, don’t let them tie me up – you know I’d

never harm a member of the Cotton family!” said ‘Dido’ after his

capture.

Francis and Anna had fourteen

children – their descendants have continued to play prominent roles in the life

of the East Coast and Tasmania’s Quaker community. Members of the family were

instrumental in the push to have Freycinet declared a national park. The Cotton

family still owns and farms at ‘Kelvedon’ today.

“The 11th

was a Sunday, but I had to march ten miles to the house of Mr Herring, whose

estate is ‘Apsley’. I do not think I ever saw such a road. I had seen no rain

since I left Oatlands but hereabouts it had fallen in plenty, and in consequence

great doubts were expressed at Bicheno as to whether I could get across the

river [I forget the name] which for three days had been impassable to man or

horse. By wading nearly up to my middle, I got across in safety, and after

wading another stream knee deep and repeatedly walking many yards at a time in

eight to ten inches of water on the road, and many, many more yards in muddy

slush, I got to Apsley, a nice figure for a drawing room!” F.J. Cockburn’s

journal of a walking tour of the East Coast in the 1850’s.

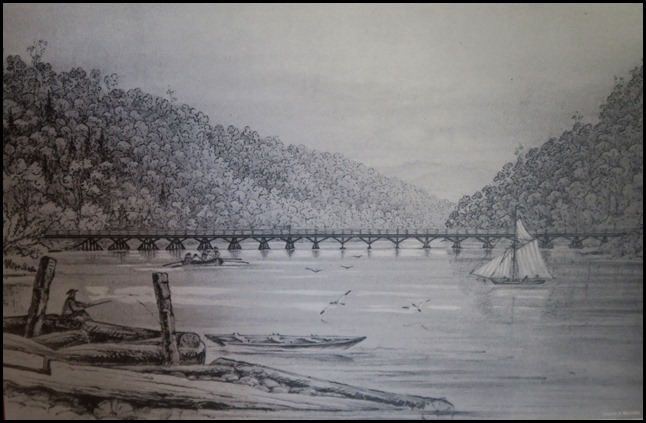

“At the seaward end of the rocky

Paradise glen, where Prosser’s River widens to a small estuary, the Meredith Bridge spans the stream, connecting the northern

and southern portions of the East Coast. Before its erection, the broad river

river formed a serious obstacle to communication, and I well remember, on my

first journey hither, being amazed by seeing two horsemen riding out, as it

seemed to me, straight into open sea, as though bound for Maria Island, when I

was informed that they were in reality making their way across the river by

following the course of a long spit of sand, which forming a comparative

shallow, enabled travellers at certain periods of the tide to gain the opposite

beach, though not without considerable risk and a thorough wetting.” Louise

Anne Meredith ‘Our Island Home – A Tasmanian Sketch Book’, 1879.

“Sir

May I be permitted to occupy a

small space in your journal to call attention to a serious inconvenience which

travellers by coach from George’s Bay to the Corners frequently have to suffer?

I refer to the practice of arriving too late at the Corners to catch the express

train to Hobart.

No blame is attached to the

horses – but the coachman dawdles away valuable time in a manner which proclaims

him a past master in the art of ‘how not to do it’. Time is wasted in every

conceivable way. It takes longer to change horses, longer to strap the luggage

on the roof, longer to collect the mail bags, longer to buckle a strap or fix a

chain, longer to light a pipe and longer to spin a yarn with a friend than on

any coach I have ever travelled with in my life.

I am not likely to visit the East

Coast again for some time and when I do I shall certainly adopt some mode of

conveyance other than the coach. But the increasing importance of the East Coast

tin mining district and the large number of persons who are required to travel

thither on business render it important that regularity and punctuality should

be strictly observed.

Yours etc,

A Visitor

March 29 1882”

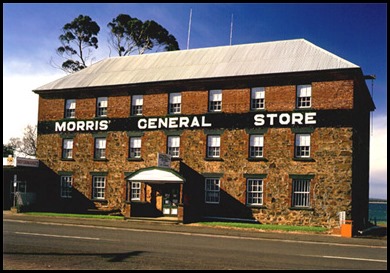

“Observe ladies and gentlemen,

the astonishing brilliance of a five candle-power electrical light globe!”

William Morris exhibiting electric light in Hobart, 1882.

James Morris brought his wife and

baby to Hobart Town from Essex in 1853 – his mother, sister and brother William

followed soon after.

The Morrises were successful and

entrepreneurial business people. James worked with well-known Hobart Firm Mather

& Son before branching out on his own in Swansea, where he bought the

business that stayed in the family for generations. William tried his luck on

the mainland goldfields before going into business in the North East and then

Hobart, where he demonstrated one of the town’s first installations of electric

lighting in 1882.

Today, the fine old Morris

building is a Swansea landmark, one of the last and best country general stores,

where you can buy anything from chewing gum to gumboots.

Silence and calm seem to

be the keynotes of life in St Helen’s. Here and

there in the broad main street could be seen parties of well-dressed ladies

sauntering about enjoying the beauties of the day. From the direction of the tin

mines could be seen strings of ore-laden carts, the full-fed teams well under

command. On the road, parties of Chinamen trudged along in single file, as is

the wont of the patient Mongolians. A small steamer was moored to the wharf and

a handful of lumbers were engaging in discharging the cargo and stacking tin

ore. All, however, was going on without noise or apparent

effort.

“You see,” our guide remarked,

“We do not fash ourselves with frantic work. Life is worth living at this place

without rushing at it or through it. We have our local circulating library, our

little literary and reading clubs, our concerts and picnics. Who could fail to

be content in a place like this?” Travel Diary of Henry Button, touring the

East Coast in the 1880’s.

“We became acquainted with the

‘Tasmanian boy’ as we cycled along the coast. He is the same tough, cheeky and

carefree young terror as his species on the mainland. The traveller is fair game

to this young imp. Seeing us toiling slowly uphill, he would jeer. ‘Aw, it’s the

pace wot kill, ain’t it mister?.’ And once on a terrifying downhill run, a young

Tasmanian of twelve summers or so, literally festooned with dead rabbits, popped

up over a stone and yelled ‘Hey mister, got the time on yer?’” Cycling

journalists TM Hogan and Hal Gye, circa

1920.

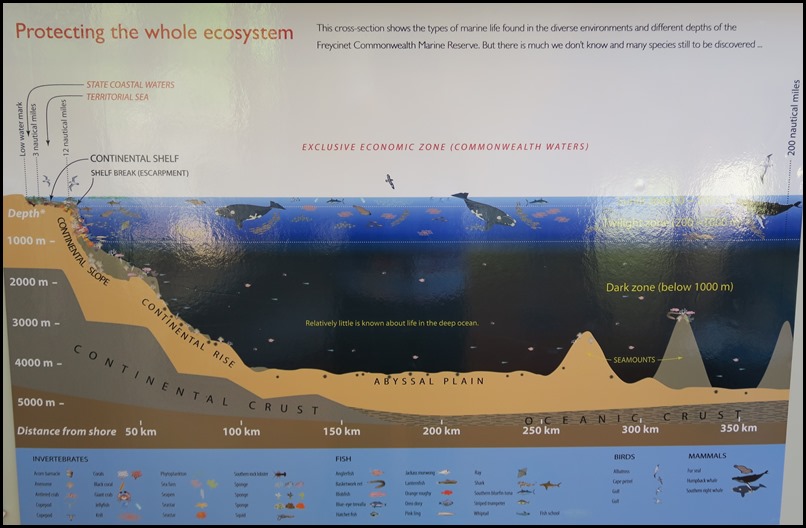

We had a look around the natural history end.

We looked at a cross section of the local Marine Reserve and ‘loved’ one

particular creature.

Barry

Blobfish.

Barry – otherwise known

as Psychrolutes sp, is not happy out of water. Psychrolutes is Greek for

‘someone that has had a cold bath’. Blobfish grow to about 70 cms and live in

very deep waters from 600 to 2800 metres. The pressure down there is up to two

hundred and eighty times higher than the surface – if humans went to such depths

we would be so squashed that we wouldn’t look too good either. So how do

blobfish survive? Their jelly-like flesh enables them to cope. If they had a

full skeleton, lots of muscles and air-filled cavities like other fish [and us],

the extreme pressure at the bottom of the ocean would make the blobfish

collapse. Having very few muscles means they can’t swim around so, they sit on

the dark ocean floor and eat any food that happens to pass by. They are the

ultimate deep sea couch-potato.

From fish to blob.

A message from Barry. “In

complete darkness, sitting at the bottom of the ocean, thousands of metres deep

and under enormous crushing pressure. Next thing I was brought to the surface in

a net and I went all flabby. I don’t normally look like this – I’m actually a

compact little fish. Now I’ve been voted ‘the ugliest creature on

earth’!”

ALL IN ALL LOVELY TO READ

ABOUT REAL PEOPLE

REALLY WELL

PRESENTED |