Battle of Spioenkop

|

Visit to the Battlefield of Spioenkop (or Spion

Kop)  After a very tasty lunch we headed toward Spioenkop

(the word “spioen” in

Afrikaans means “spy” or “look-out”, and “kop” means “hill” or

“outcropping”), a view along the way.

About ten miles I thought, until the

Wicked Witch with the surprisingly nice voice, took us along an unsealed road –

and my, was it unsealed. We bumped along between farm

fields for half an hour and eventually arrived at the gate at

four-thirty.

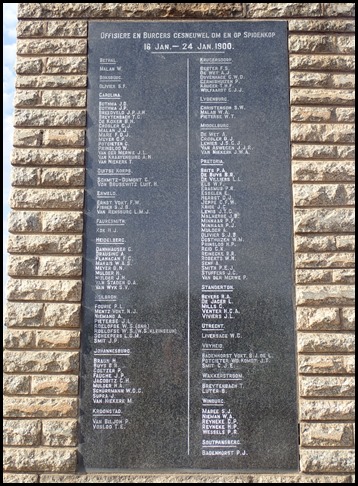

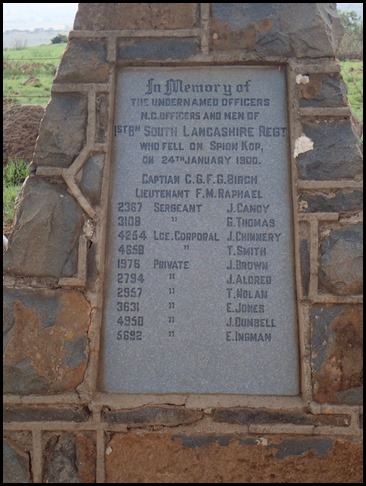

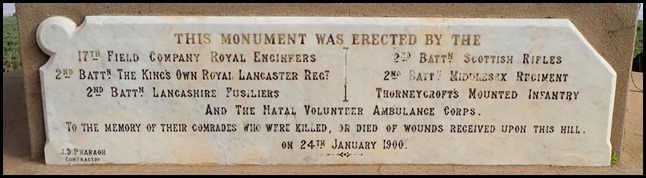

The wall

plaque beside the main gate. The lovely man at the gate was concerned

that the Battlefield Memorial closed at five but I promised faithfully we would

be on time and that our visit was all for Joe (son) who is such a massive

Liverpool supporter that his son has the initials KOP. He laughed as I leapt out

of the car when I saw inside his gatehouse.......

.......did not expect to see this.

Liverpool memorabilia..... Quote from This is Anfield: The claim is that survivors from that battle ended up

christening the new stand at Anfield, built in 1906, Spion Kop in memory of

their fallen comrades. Even today, the origins of that name and the true nature of where

it came from can be heard on the terraces, with the Kop singing ‘Poor Scouser

Tommy’ with regularity; though the song doesn’t refer directly to that battle,

it speaks of a fallen soldier and a Liverpudlian who comes from the Spion

Kop.

The first recorded reference to a sports terrace as "Kop" related to Woolwich Arsenal’s Manor Ground in 1904. A local newsman likened the silhouette of fans standing on a newly raised bank of earth to soldiers standing atop the hill at the Battle of Spion Kop. Two years later in 1906, Liverpool Echo sports editor Ernest Edwards noted of a new open-air embankment at Anfield: "This huge wall of earth has been termed 'Spion Kop', and no doubt this apt name will always be used in future in referring to this spot". The use of the name was given formal recognition in 1928 upon construction of a roof. Many other English football clubs and some rugby league clubs use the word ‘kop’. Villa Park’s old Holte End was historically the largest of all Kop ends, closely followed by the old South Bank at Molineux, both once regularly holding crowds in excess of 30,000. However, in the mid-1980s work was completed on Hillsborough’s Kop which, with a capacity of around 22,000, became the largest roofed terrace in Europe. Liverpool's Spion Kop was closed and demolished in 1994 (to comply with requirements of the Taylor Report), which made all-seater stadiums obligatory in the highest two divisions of English football. A new Spion Kop was built in its place with 12,390 seats.    We bumped over speed/drainage ridges

going up a steep hill. Bear stopped below the first memorial

- African and headed for the car park. I ran up a slope to photograph

pressed for time.

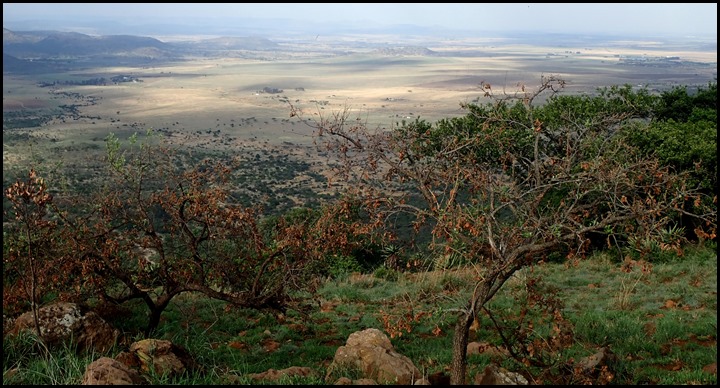

The view from the

top.......

......and where much of the battle occurred.

The Anglo Boer

War: Britain had for a time, in the latter 19th century, tried to gain

control over the Zulu Afrikaansche Republiek (ZAR). When Sir

Alfred Milner became governor of the Cape Colony and High Commissioner

for South Africa the policy of aggressive imperialism was intensified.

President Paul

Kruger was determined to preserve the independence of the ZAR, but had in

negotiations with the British made several concessions. ZAR/British relations

deteriorated and eventually war broke out between Britain and the Boer Republics

on the 11th of October 1899.

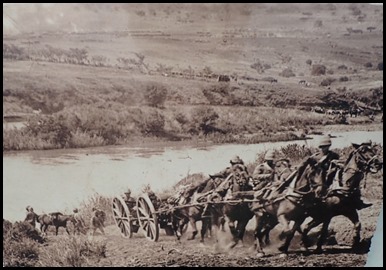

British troops disembarking at Durban and Boer commandos arming themselves.

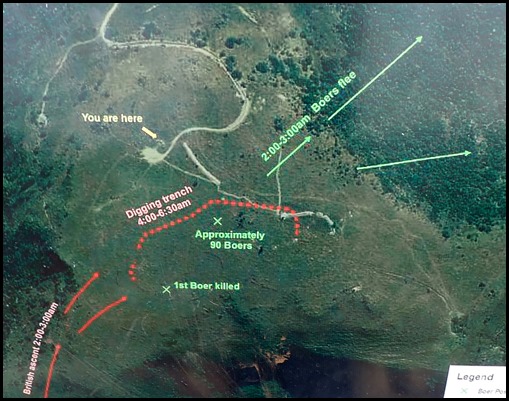

Our map

and information sheet describes this battle as “the most futile and bloodiest of

the five battles fought in an effort to relieve Ladysmith and Bergville”.

Boer troops moved

into the British Colony of Natal and laid siege to

Ladysmith, where large numbers of British forces were stationed. The Boers, in

response to the arrival of thousands of British troops in Durban, took up

positions along the Thukela River near Colenso. On the 15th of December 1899 a

British force of 19,400 men under Sir Redvers

Buller, suffered a humiliating defeat. A Boer force of 4,500 under General Louis

Botha took up positions along the Thukela River near Colenso and repulsed

Buller’s force, causing 1,000 British casualties.

On the 10th of January 1900, with a force swelled to

24,000 men, Buller moved to the upper Thukela near Spioenkop. His

second-in-command, Lt.Gen. Sir Charles Warren, under

orders, crossed the Thukela with 15,000 men on the

17th of January 1900, but they were repulsed by 2,000 Boers on iNtabamnyama.

Warren then decided to attack Spioenkop, the highest point on the Boer defense

line.

Warren decided to capture

Spioenkop with a surprise, night attack. A force of 1,700 under Major General Edward Woodgate departed under drizzling,

pitch dark conditions at 21:00 on the 23rd of January 1900 and climbed a spur

from the south west.

By 02:00

they reached the last plateau leading to the summit

(bottom left of the map). The summit of Spioenkop was at the time

occupied by a force of about 100 Boers.When the British reached the top they halted and fixed bayonets.

The men then advanced in lines. As the British approached this area a loud

challenge from the Boer watch, followed by rifle fire issued out of the

darkness.

As the Boers reloaded, the

British charged and bayoneted one of the Boers (place marked with a simple cross). The remaining Boers fled

the summit via the north eastern slopes and raised the alarm in the Boer

encampments below. It appeared that the summit had been captured at little cost

to the British.

After gaining control of the

summit, Woodgate gave instructions for the hill to be fortified, and a shallow

trench and breastworks were constructed. (It is said that there

were only twenty shovels and an equal number of picks in use as a thousand

soldiers stood by). The trench faced north and was about four hundred metres

in length and probably no deeper than forty centimetres. The stones and soil

from the trench were formed into a low wall. The breastwork formed the extreme

left of the British position. By 06:30 the trench was complete and the men

rested, waiting for the mist to lift. The field of fire from this part

of the trench was good. What remains of this part of

the trench.

Once General Botha became aware

of the British success he gave orders for the Boers to occupy the surrounding

slightly lower hills, he believed that Spioenkop was defensible from these

positions, and it was for this reason that he had in the first place positioned

only a few men on the summit. 400 men were ordered to climb the steep north-east

slopes and attack the British on the summit. They would be supported by rifle

fire from the surrounding hills and seven field guns placed at strategic

positions around Spioenkop. These preparations occured under cover of darkness

and the thick mist.

The Battle of

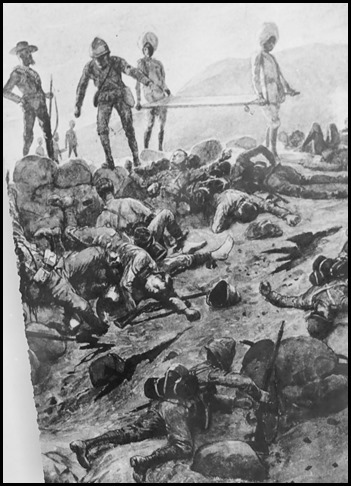

Spioenkop. The first burghers reached the summit under cover of the

mist, but were repulsed by Woodgate’s men. As soon as the thick mist cleared

from Spioenkop at about 08:30, the British found themselves exposed to a

terrific hail of rifle and shell fire. This assault continued for most of the

day. Woodgate was soon mortally wounded, resulting in

great confusion as to who was in command. Due to severe losses suffered and the

intense heat, about 200 Lancashire Fusiliers capitulated at about 13:00. The

arrival of reinforcements from the Middlesex Regiment and the Imperial Light

Infantry prevented a complete collapse of the British line, and thwarted a Boer

outflanking attempt from the southern slopes of Spioenkop.

Late in the afternoon, another

force, the King’s Royal Rifles, drove Gen. Burger and his men from the Twin

Peaks. The British failed to exploit this success and withdrew from Spioenkop

under cover of darkness. From about 15:00 the battle on the summit became

relatively static, with the British grimly holding position whilst being

bombarded by artillery fire.

Once it became dark Lt.Col. Thorneycroft, at this time in

command ordered a retreat back to camp.

Many of the Boers had by this

time also fallen back. At sunrise the following morning, the Boers found that

the British had retreated, and that only the dead and

wounded remained on the summit. The British had suffered a major setback.

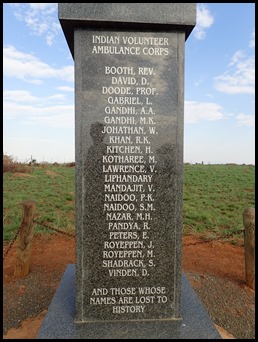

Indian stretcher

bearers on the summit after the battle.

On that day a cease-fire was

agreed so that the dead could be buried. The Boer line of defense was still

intact and Buller had once more failed to relieve Ladysmith.

Casualties. Boer killed – 68. Wounded - 134. British

killed – 343. Wounded – 563. Missing /Prisoner – 187.

One month later, on the 27th of

February 1900, Buller finally managed to break the Boer siege of Ladysmith,

which had lasted for four months.

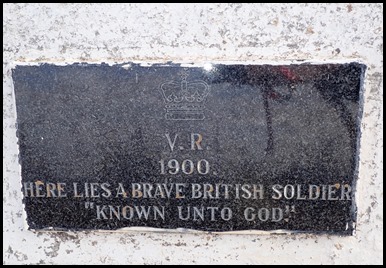

The British mass grave and as we saw it

today.

Looking up from the curve of the hill.

H.S.M. McCorquodale, unmarked

and Thomas Flower Flower-Ellis.

The fallen of the

Lancashire Regiment.

The Hon Nevill

Windsor Hill Trevor aged thirty-one has his headstone between two unknown soldiers.

Memorial to the Indian stretcher bearers, the Indian Volunteer Transport Corps

and the Indian Volunteer Ambulance

Corps.

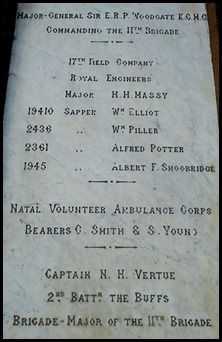

The largest of the

memorials to the British men lost.

The far ends of

the massed grave by one of the breastworks.

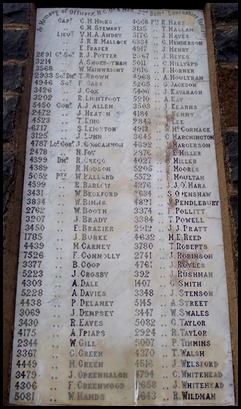

Lt. James

Maleock aged 26, Eric Fraser and 2nd Battalion Buffs (memorials along the massed

grave).

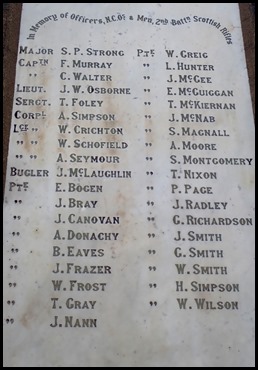

4 Officers and 38 NCO’s

from Middlesex.

Bear posed with

some twigs for Joe. There was a story that a tree was carried back from

Spion Kop that became the crossbar at the kop end of the Liverpool football

ground – well as we can’t take a tree, the twigs are the nearest

thing.........

Haunting last

image begs the question – what it is all for ??? As

we said ‘farewell’ to the lovely man on the gate a few minutes to five, I

mentioned that it was Joe’s birthday – hence the visit. He rummaged around in a

cupboard in his gatehouse and came back to give me an actual bullet from the

battlefield. Wow.

As we drove away Kimi took this

wonderful sky and scenic picture.

ALL IN ALL LADS SO FAR FROM

LIVERPOOL RIP

AN AMAZING

STORY |