Mary Prince

|

Mary

Prince

At the Salt Museum there was an

information board and 'freedom wall' dedicated to Mary

Prince, catching our attention and a need to find out more about this

extraordinary woman. Mary Prince was the daughter of slaves, she was born in

Brackish Pond, now known as Devonshire Marsh, Bermuda

around 1788. Her father was a sawyer - owned by David Trimmingham and her mother

a house-servant. Mary and her mother were the property of Charles Myners. When

Myners died, Mary and her mother were sold to

Captain Williams. Mary became the personal slave of his wife, Betsey. When she

was twelve years old Mary was hired out to another plantation five miles away.

Mary Prince worked as a domestic

slave, out in the fields and was constantly flogged by her new mistress. She

later wrote "To strip me naked - to hang me up by the wrists and lay my flesh

open with cow-skin, was an ordinary punishment for even a slight

offence".

Mary was sold for thirty eight pounds sterling (2009: £2,040) to Captain John Ingham, of Spanish Point, but never took easily to the indignities of her enslavement and she was often flogged. As a punishment, Prince was sold to another Bermudian, probably Robert Darrell, who sent her in 1806 to Grand Turks, which Bermudians had used seasonally for a century for the extraction of salt from the ocean. Salt was a pillar of the Bermudian economy, but could not easily be produced in Bermuda, where the only natural resource were the Bermuda cedar trees used for building ships. The industry was a cruel one, however, with the salt-rakers forced to endure exposure not only to the sun and heat, but also to the salt in the pans, which ate away at their uncovered legs.

After around ten years working on

Grand Turk, Mary returned to Bermuda. In 1818 she was sold to John Wood, a

plantation owner who lived in Antigua, for three hundred dollars. She later

wrote, "My work there was to attend the chambers and nurse the child, and to go

down to the pond and wash clothes. But I soon fell ill of rheumatism, and grew

so lame that I was forced to walk with a stick".

Mary Prince began attending meetings

held at the Moravian Church. She later wrote, "The Moravian ladies taught me to

read in the class; and I got on very fast. In this class there were all sorts of

people, old and young, grey headed folks and children; but most of them were

free people. After we had done spelling, we tried to read in the Bible. After

the reading was over, the missionary gave out a hymn for us to

sing".

While in Antigua she met the widower

Daniel Jones, a former black slave who had managed to purchase his freedom.

Jones now worked as a carpenter and cooper, asked Mary to marry him. She agreed

and they married in the Moravian Chapel in December 1826. John Wood was furious

when he found out and once again she had to endure a severe punishment, another

beating with a horsewhip.

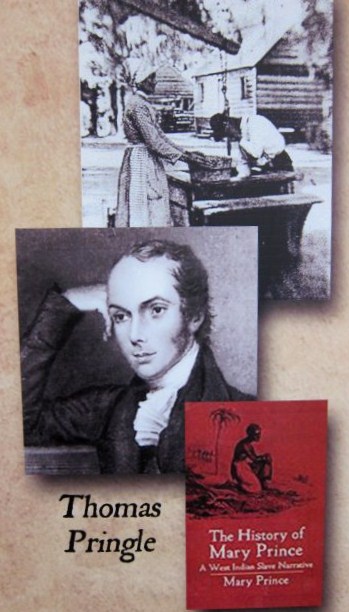

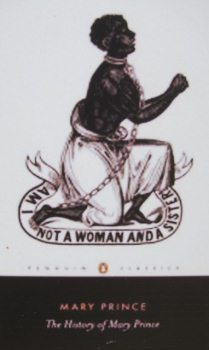

John Wood and his wife took Mary as

their servant to London in 1828.

Although slavery was illegal in Britain, Mary had no means to support

herself, and could not have returned to her husband without being re-enslaved.

She remained with Wood until they threw her out. She took shelter with

the Moravian church in Hatton

Garden. Within a few weeks, she had taken employment with Thomas

Pringle, an abolitionist

writer, and Secretary to the Anti-Slavery

Society. Prince arranged for her narrative to be copied down by

Susanna Strickland and it was published in 1831 as The History of Mary

Prince, the first account of the life of a black woman to be published in

the United Kingdom. The book had a galvanizing effect on the anti-slavery

movement. Scandalised by its account, John Wood sued the publishers for libel stating

the book, "endeavoured to injure the character of my family by the most vile and

infamous falsehoods". but his case failed. Subsequent attempts were made to

tarnish Mary Prince's reputation, particularly by James MacQueen and James

Curtin, both supporters of slavery. In turn, she and her publisher sued for

libel, which suit they won. Prince remained in England until about 1833. The first black woman to be

seen rallying and speaking in public in the UK.

The extraordinary testament of

ill-treatment and survival was a protest and a rallying-cry for emancipation

that provoked two libel actions and ran into three editions in the year of its

publication. Prince inflamed public opinion and created political havoc. The

sufferings and indignities of enslavement been seen through the woman struggling

for freedom in the face of great odds.

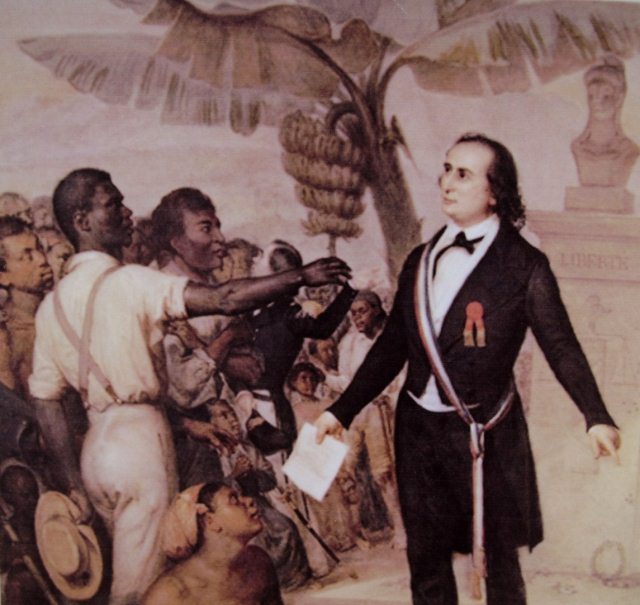

Thomas Pringle (January 5, 1789 – December 5, 1834) was a Scottish

writer, poet and abolitionist,

known as the father of South African Poetry, being the first successful English

language poet and author to describe South Africa's scenery, native peoples, and

living conditions. Born at Blaiklaw (now named Blakelaw), four miles south of Kelso

in Roxburghshire,

Thomas Pringle studied at Edinburgh

University where he developed a talent for writing. Being lame, he did not

follow his father into farming, but worked as a clerk and continued writing,

soon succeeding to editorships of journals and newspapers. One of his poems

celebrating his Scottish heritage came to the attention of the novelist Sir

Walter Scott, by whose influence, whilst facing hard times and unable to earn a

living, he secured free passage and a British Government resettlement offer of

land in South

Africa, to which he, with his father and brothers, emigrated in 1820.

Being lame, he himself took to literary work in Cape

Town rather than farming, opened a school with fellow Scotsman John

Fairbairn, and conducted two newspapers, the South African Journal, and

South African Commercial Advertiser. However, both papers became

suppressed for their free criticisms of the Colonial Government, and his school

closed. Without a livelihood, and with debts, Thomas returned and settled in London. An anti-slavery article which he had written in South Africa before he left, was published in the "New Monthly Magazine", and brought him to the attention of Buxton, Zachary Macaulay and others, which led to his being appointed Secretary of the Anti-Slavery Society. He began working for the Committee of the Anti-Slavery Society in March 1827, and continued for seven years. He offered work to Mary Prince, an escaped slave, enabling her to write her autobiography, which caused a sensation arising from failed libel actions and went into many editions. He also published African Sketches and books of poems, such as Ephemerides. As Secretary to the Anti-Slavery Society he helped steer the organisation towards its eventual success; in 1834, with a widening of the electoral franchise, the Reformed British Parliament passed legislation to bring an end to slavery in the British dominions - the aim of Pringle's Society. Pringle signed the Society's notice to set aside on the 1st of August 1834 as a religious thanksgiving for the passing of the Act. However, the legislation did not came into effect until August 1838, sadly Thomas Pringle was unable to witness this moment; he had died from tuberculosis in December 1834 at the age of forty five.

Excerpts from The History of Mary Prince, A West

Indian Slave, Related by Herself. "At length her put me on board a

sloop, and to my great joy sent me away to Turk's Island (ed: Grand Turk). I was

not permitted to see my mother or father, or poor sisters and brothers, to say

goodbye, though going away to a strange land, and might never see them again. Oh

the Buckra people who keep slaves think that black people are like cattle,

without natural affection. But my heart tells me it is far otherwise.

We were four weeks on the voyage, which was unusually long.

Sometimes we had a light breeze, sometimes a great calm, and the ship made no

way; so that our provisions and water ran very low, and we were put upon short

allowance. I should almost have starved had it not been for the kindness of a

black man called Anthony, and his wife, who had brought their own victuals (ed:

food), and shared them with me.

When we

went ashore at Grand Quay, the captain sent me to

the house of my new master, Mr. D. to whom Captain I. had sold me. Grand Quay is

a small town upon a sandbank; the houses low and built of wood. Such was my new

master's. The first person I saw, on my arrival, was Mr. D., a stout sulky

looking man, who carried me through the hall to show me to his wife and

children. Next day I was put up by the vendor master to know how much

I was worth, and I was valued at one hundred pounds

currency.

I was immediately sent to work in the

salt water with the rest of the slaves. This work was perfectly new to me. I was

given a half barrel and a shovel, and had to stand up to my knees in the water,

from four o'clock in the morning till nine, when we were given some Indian corn

boiled in water, which we were obliged to swallow as fast as we could for fear

the rain should come on and melt the salt. We were then called again to our

tasks, and worked through the heat of the day; the sun flaming upon our heads

like fire, and raising salt blisters in those parts that were not completely

covered. Our feet and legs, from standing in the salt water for so many hours,

soon became full of dreadful boils, which eat down in some cases to the very

bone, afflicting the sufferers with great torment. We came home at twelve; ate

our corn soup as fast as we could, and went back to our employment till dark at

night. We then shoveled up the salt in large heaps, and went down to the sea,

where we washed to the pickle (ed: the salt) from our limbs, and cleaned the

barrows and shovels from the salt. When we returned to the house, our master

gave us each an allowance of raw Indian corn, which we pounded in a mortar and

boiled in water for our supper.

We slept in a long shed, divided into

narrow slips, like the stalls used for cattle. Boards fixed upon stakes driven

into the ground, without mat or covering, were our only beds. On Sundays, after

we had washed the salt bags, and done other work required of us, we went into

the bush and cut the long soft grass, of which we made trusses for our legs and

feet to rest upon, for they were to full of salt boils that we could get no rest

lying upon the bare boards.

Though we worked from morning till

night, there was no satisfying Mr. D. My former master used to beat me while

raging and foaming with passion; Mr. D. was usually quite calm. He would stand

by and give order for a slave to be cruelly whipped, and assist in the

punishment without moving a muscle of his face; walking about and taking snuff

with great composure. Nothing could touch his hard heart - neither sighs nor

tears, nor prayers, nor streaming blood; he was deaf to our cries, and careless

of our sufferings. Mr. D. has often stripped me naked, hung me up by the wrists,

and beat me with cow-skin, with his own hand, till my body was raw with gashes.

Yet there was nothing very remarkable in this; for it might serve as a sample of

the common usage of the slaves of this horrible island.

Sometimes we had to work all night,

measuring salt to load a vessel; or turning a machine to draw water out of the

sea for salt-making. Then we had no sleep - no rest - but we were forced to work

as fast as we could, and go on again all the next day the same as

usual.

Oh the horrors of slavery! - How the

thought of it pains my heart! But the truth ought to be told of it; and what my

eyes have seen I think it my duty to relate; for few people in England know what

slavery is. I have been a slave - I have felt what a slave feels, and I know

what a slave knows; and I would have all the good people in England to know it

too, that they break our chains, and set us free.

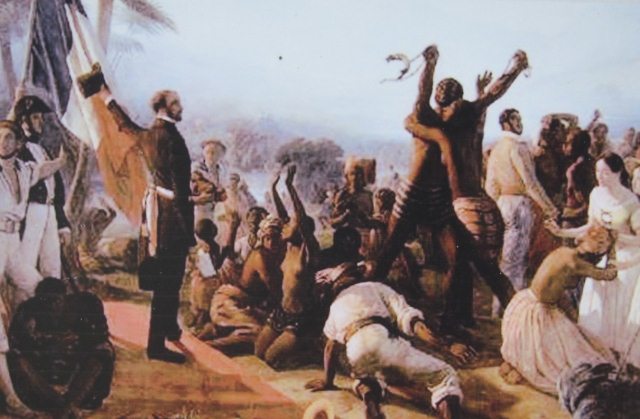

In March 1807 the British Government

outlawed the slave trade and abolished slavery in the UK. In the overseas

territories slavery was still legal, but there was to be no purchasing of slaves

directly from Africa. In fact the Royal Navy set up special patrols to board

ships and free slaves on the journey from Africa to the West Indies. Any

captured slaves became the property of the government and were placed in the

hands of the Chief Customs Officer, and could be bound in apprenticeships for up

to fourteen years........

The disparity of the rights of freed slaves in the UK and

those of the slaves in the West Indies caused serious concerns in Britain. The

Abolitionist movement grew and formed a powerful lobby. The movement put

pressure on the governments of the colonial areas, much to the disgust of these

Assemblies who disliked interference in their affairs. The Bahamas

Legislature (covering the Turks and Caicos) decided on an Apprenticeship for the

slaves. All colonies had to pass their own Abolition or Emancipation Acts, the

Bahamas doing so in 1834.

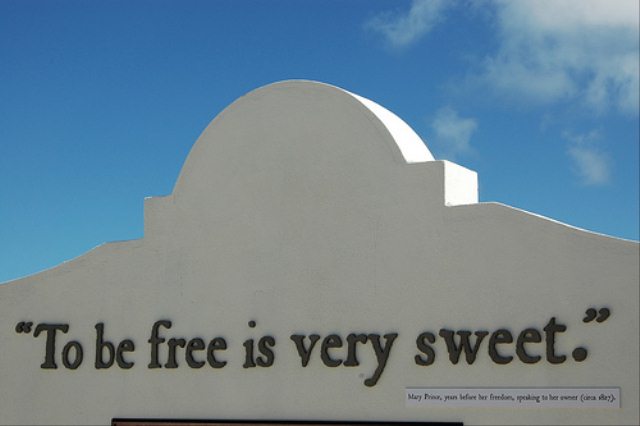

Mary Prince's efforts to free herself

and her fellow slaves in the West Indies was ultimately successful. On the 31st

of July 1833, the House of Lords passed the Emancipation Bill which would free

the slaves of the West Indies in 1834. The Mary Prince Wall, located two hundred

years later in the exact spot of her suffering, stands as a tribute to her

triumph over her former owners and life itself. It is also a tribute to the

strength of her spirit, her fortitude, her resourcefulness and her disciplined

inner self. The Mary Prince Wall asks that we take a moment to reflect on the

lady herself, her brethren, the thousands of other slaves and their descendants

who toiled here over the centuries.

Mary Prince was not only the first

black woman to escape slavery, the first female abolitionist and the first

black female to write a book - her autobiography. Her story highlights not only

the suffering and indignities of enslavement, but also the triumphs of the human

spirit.

ALL IN

ALL A VERY SPECIAL WOMAN |