Mussels

Beez Neez now Chy Whella

Big Bear and Pepe Millard

Thu 18 Sep 2014 22:47

|

Mussels in the Mussel Capital

of the World

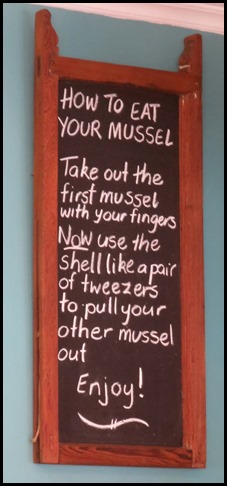

To eat a plateful of mussels in

Havelock the greenshell capital of the world, was a must-do for Bear. His bucket

list, his choice of eatery. We parked Mabel just off the main road and bimbled

across to the Mussel Pot. The fence looked like fun

and then two chaps welcomed us at the front door.

First fancying mussel chowder, Bear

chose mussels with blue cheese.

Mussels have always been regarded as

a fantastic food, not by me however. The look, texture and smell make them far

from anything I have ever deemed a life necessity to try and nary one has ever

got close to my lips, but Bear loves them. I don’t mind preparing them for him

and cook them in a variety of ways. The same goes for all things shellfish, to

watch someone swallow a raw oyster, as far as I’m concerned, pushes the vows of

marriage to their extreme limit, why not cut a flip-flop up into similar sized

portions and soak them in fish gravy, but there we are, each to his own.

Traditionally harvested from the

shoreline by local and visiting Māori, Marlborough mussels were a drawcard for

North Island Māori who would launch expeditions to gather kai moana, food of the

sea, as well as locals who would gather regularly to supplement their diet.

In 1969 a group of fishermen towed the first mussel

barge into the Marlborough Sounds and anchored it in the Kenepuru. In the past

forty-odd years since, the New Zealand aquaculture industry has evolved from a

group of innovative pioneers to a professional, specialised and premium food

production sector focused on environmental sustainability, food safety and

value-added marketing. Most farms

were originally started by independent farmers but today there is an increasing

trend for sites to be owned by seafood companies. First attempts to farm mussels were based on Spanish raft cultivation

techniques. There were superseded by the Japanese longline system which has been

adapted and improved by New Zealand operators.

In 2011 the

industry employed over three thousand New Zealanders and generated over $400

million of revenue. Of the $400 million industry revenue, $298 million was

generated in exports. Aquaculture

is already the world’s fastest growing primary industry and demand for

aquaculture products is expected to strengthen significantly as the world’s

population grows and wild-catch levels remain relatively static.

New Zealand

aquaculture products are exported to seventy nine countries and considered among

the world’s best seafood, served at parties in New York and white tablecloth

restaurants in London. The high

quality of New Zealand coastal waters and the abundance of plankton, along with

the prevalence of sheltered harbours and inlets create ideal conditions for

aquaculture.

Time to get my head down to the

business of concentrating on my fish and chips as the eating

begins.........

The New Zealand green-lipped mussel,

Perna canalicula, is endemic to New Zealand. When grown for aquiculture in New

Zealand it is produced under the trademark name Greenshell. The bulk of the

industry’s spat – baby mussels, are gathered on ninety mile beach where,

considerable quantities of new settled spat attached to seaweed are washed up on

the beaches. This spat is collected and quickly transported by air or truck to

growers in other parts of the country. local spat catching also occurs in Golden

Bay and Marlborough in selected bays. The spat is seeded out on spat ropes using

cotton stocking at approximately one to five thousand per metre of rope. After

three to six months, the nursery lines are lifted and the young spat are

stripped from the ropes and reseeded on a final production rope at approximately

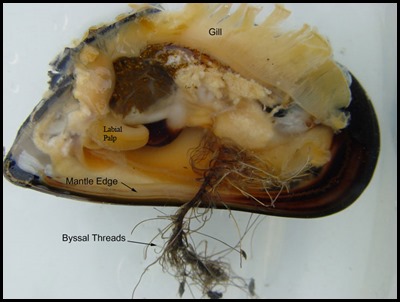

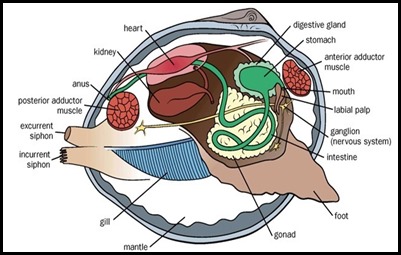

one hundred and fifty to two hundred per metre. The mussel has a foot –

sometimes called a tongue, which allows it to move over surfaces. Once the

mussel finds a suitable site, fluid is shot down a groove in the foot and

solidifies on contact with the sea water, anchoring the mussel in place. Mussels

take between fifteen and eighteen months to grow to a shell size of seventy to a

hundred millimetres.

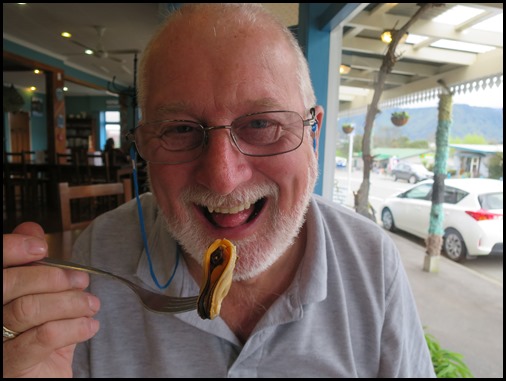

Silly me, I ask for a closer look.

Suddenly interested I ask Bear about his experience with byssal threads. You can’t

taste anything an they are not stringy which I thought they might be, but

chewing the whole thing there are lots of textures. Oooo, perhaps too much information, I swallow and duck to my side

salad. An interesting thing I did read, here in the

restaurant, they don’t automatically throw away a shell that has stayed shut,

neither have I. I have always opened and sniffed. Its all to do with what

happens to the adductor muscle of the mussel I say knowledgably to himself, some

disintegrate completely in hot water, some fall off one side. Oh, its a muscle is it, I didn’t know that, never tried it

before. What did I say, silly me, next thing he’s prising one off to

taste, well. Tastes like squid and chewy, not easy to

get off though. Oh dear, have I got to try not to watch as he

rummages through his empty shells thus far and eat those he hasn’t got to yet.

Yep.

The diet of a mussel includes single

cell algae and planktonic animals. Mussels are filter feeders and each mussel is

capable of filtering about three hundred litres of water per day. With

approximately nine hundred million mussels grown commercially in Marlborough

Sound, this means a massive two hundred and seventy million tonnes of water is

moved by mussels every day. The single biggest factor that can affect the water

quality is the land run-off as a result of rainfall. A number of rain gauges are

positioned throughout the mussel farm areas which are monitored by the New

Zealand Food Safety Authority. The data collected determines which farms are

open or closed for harvesting. The New Zealand mussel industry is known to

operate one of the strictest quality assurance programmes in the

world.

When the mussel farm is declared

open, a harvesting boat will select a designated line and hauls on board the

rope that is fully laden with mussels. The mussels are removed from the rope and

are then de-clumped and washed. The mussels will go through a quick initial

grading and are then collected into large bags for transporting. A single

harvester will typically collect between fifty and seventy tonnes of mussels

each day. The flow of mussels through the processing chain is rapid. The bulk of

production takes less than thirty minutes from the beginning of the cycle to the

final packaging for domestic or international distribution. Mussels are processed into many product

forms including live, chilled, vacuum packed, frozen whole or half shell, layer

packed meat, smoked marinated, crumbed, powdered, dried and stuffed. When the mussels arrive at The Mussel Pot they are checked to

ensure all are alive and in good condition. The beards are trimmed purely for

aesthetic purposes. The chef does not rip the beard out, as this kills the

mussel. Well over half the local mussels contain the New Zealand pea crab.

Current research is being done on the effects of the pea crab on the growth and

ways to eliminate them from mussel farms. The Mussel Pot

do not add salt to their mussels, they are naturally salty as they are so fresh

and have not been constantly washed with fresh

water.

The different

sexes of mussels can be identified by their colour, I asked

Bear to tidy his chosen chap up for a photograph. The flesh of a sexually mature male is creamy white while a female is

reddish-apricot. Reproduction

between male and female mussels happens outside the shell. Eggs and sperm are

discharged into the water and fertilisation takes place. Most spawning occurs in

late spring and early autumn but mussels have been known to be opportunistic and

take advantage of favourable conditions of plentiful food and ideal

temperatures.

At last, to my relief I thought the

empty plate, the pile of empty

shells meant I could return to normal life, no Bear saw the juice in the bottom of his pot and set about it with great gusto. I went back to busying

myself reading the factoids.

ALL IN ALL NOT FOR

ME

YES

PLEASE |