Early Relationships

Beez Neez now Chy Whella

Big Bear and Pepe Millard

Sat 9 Jan 2016 23:47

|

Early Relationships with the Aboriginal

People  In a side room off the main hall we read about the early

relationships between the First Fleet and the local Aboriginal

people.

Clans of the

Sydney Region: Australia holds an extraordinary diversity of Aboriginal

cultures, with an estimated two hundred and fifty different languages once

spoken across the continent. Even in the relatively small region of Sydney there

were at least thirty district clan groups, speaking several languages, including

Darag and Dharwal. Each clan was associated with specific areas of land, and

distinguished by totems [usually animals] and unique cultural elements such as

songs, dances, body decorations and designs.

Gadigal land, where the Museum of

Sydney now stands, covered the south shore of Sydney Harbour from Watsons Bay to

Sydney Cove.

Names for clans were recorded with

various spellings and colonial confusions, so mapping them today is difficult.

The clan names in brown were identified by British Officers of the First Fleet.

Other names were recorded later and may refer either to clans or to places where

Aboriginal people lived after the impact of diseases and the encroachment of

European settlers on their land. While incomplete, this map indicates some of

the known clans and groups before and after

contact, showing the complexity and ongoing variety of Aboriginal communities in

the Sydney region.

Gadigal Place: The Aboriginal people

who encountered the First Fleet in 1788 belonged to a sophisticated and

culturally diverse population whose ancestors had lived in this region – now

called Sydney – for at least forty thousand years.

The coastal Eora [meaning ‘people’]

were saltwater people, who lived on the rich resources of the harbour and

rivers. They excelled at fishing and manoeuvring simple bark canoes –

nowey – through the roughest surf. On display in this gallery are traditional tools and weapons, made by Aboriginal people

today, representative of the lifestyles of the clans of this

region.

Fifteen months after the arrival of

the First Fleet, Sydney’s Aboriginal clans were decimated by an outbreak of

smallpox, which caused terrible suffering and social upheaval. It is estimated

that the disease killed between fifty and ninety per cent of the

population.

Yet, through cultural resilience and

astonishing adaptability, the Aboriginal people of Sydney have survived. They

are today a dynamic part of the city with deep spiritual connections to this

land. This gallery is dedicated to the Gadigal clan and all Aboriginal people of

the Sydney region.

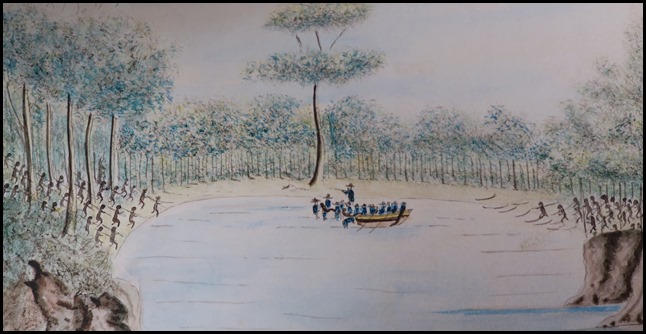

The Taking of Colebee and Bennelong. 25th of November 1789

by William Bradley,

1790.

At first the Aboriginal clans of

Sydney were wary of the new colony, and kept their distance. Governor Phillip

wanted to build friendships with the local people, to limit conflict and to

learn about local resources. With food supplies dwindling by 1789, this seemed

ever more urgent. So Phillip took a desperate step: kidnap.

First Arabanoo was captured, and when

he died of smallpox, two more men were taken. Bennelong of the Wangal tribe and

Colebee of the Gadigal were lured to a boat with the promise of fish and seized

by marines at Manly Cove.

Taken back to the colony, shaved and

clothed, the Aboriginal men were detained on this very site, in the first

Government House. Colebee escaped within a few weeks, with a leg-iron still on

his ankle, but Bennelong, who was well liked by his captors, stayed for six

months.

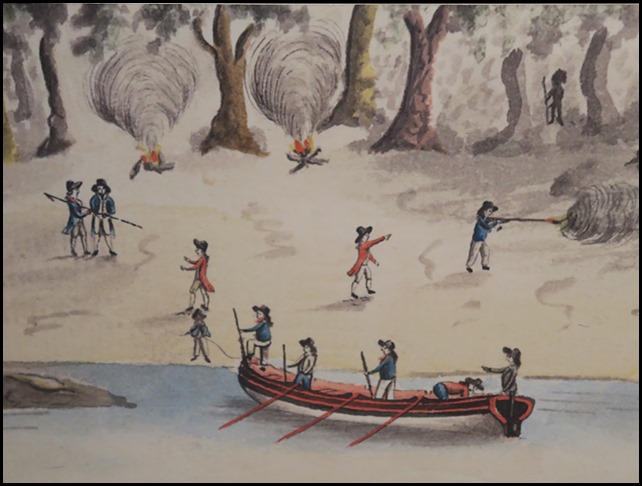

The Governor making the best of his way to the boat after

being wounded with the spear sticking in his shoulder. This painting by a Port

Jackson painter, circa 1790 along with the next two seen below.

What happened next would shock the

infant colony. Less than a year after the kidnapping, Bennelong and Colebee

invited Governor Phillip to visit manly, where locals were feasting on a whale.

An exchange of gifts and friendly conversation took place, then suddenly a man

named Willemering came forward and speared Phillip in the shoulder.

Was this daring act of violence

towards the colony’s leader an act of war ? Or perhaps just a misunderstanding ?

Both seem unlikely given the friendly exchanges that had just taken place and

peacemaking that would follow. Today, we believe Phillip’s spearing may have

been ritual payback.

Under Aboriginal Law, payback was

demanded for crimes committed. The accused faced the spears or clubs of the

family and friends of the wronged person, after which forgiveness and

reconciliation could occur. As the senior man in the colony, Phillip was held

responsible for multiple crimes committed against Eora – from kidnapping and

violence to chopping down trees and taking land.

Mr Waterhouse

endeavouring to break the spear after Governor Phillip was wounded.

Though Governor Phillip’s injury was

terribly painful, the weapon Willemering used to spear him lacked the jagged

stones of a death spear and entered just below the shoulder, injuring no vital

organs. This suggests the intention was to wound rather than kill the governor.

Ban Nel Lang

meeting the governor by appointment after he was wounded by Willemering

in September 1790.

After being speared, Governor Phillip

ordered that no retaliation should take place. Perhaps he sensed the incident

had been brought on by his own actions and those of his countrymen. Retaliation

would have stirred up tensions again, and this was the last thing he

wanted.

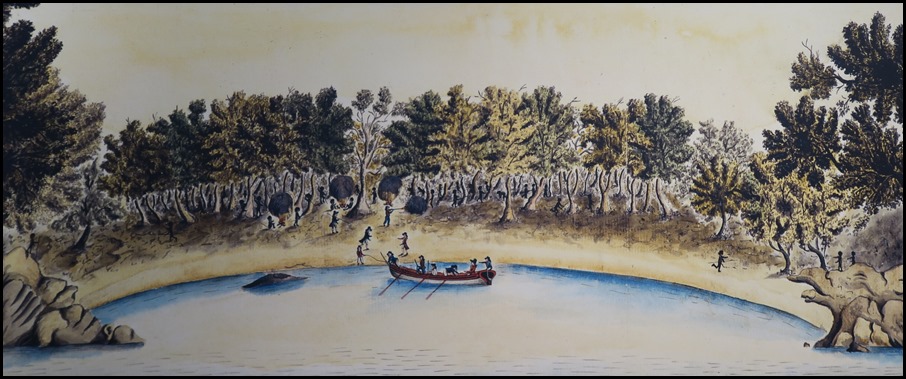

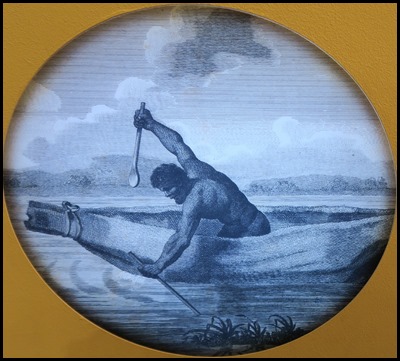

The painting above depicts the moment

of reconciliation between Bennelong and Phillip, as they rowed out to their

first meeting after the spearing. Bennelong is in the canoe at left closest to

the longboat, holding up his paddle to signal. His wife Barangaroo is believed

to be the woman in the next canoe.

Soon after this meeting, with payback

done, Eora began to ‘come in’ to the settlement and make peace with the

strangers. The colonists saw this as a great moment of reconciliation, little

knowing the conflict and violence yet to come. Bennelong and Phillip’s carefully

brokered peace would prove to be all too brief.

Warriors of New

South Wales. John Heaviside Clark, 1813.

At first Aboriginal people tried to

apply payback and other principles of their Law in dealing with the colonists –

but it didn’t work. The strangers had shown they were invaders and ‘aliens’

outside the Law by stealing land, abducting women and children, and other

offences.

Conflict came to a head when the

settlement spread into the fertile Hawkesbury River area. The colonists burnt

the forests and planted corn where native yams and other staples once grew. When

Aboriginal families tried to reach the water or gather the corn now growing on

their land, some outraged settlers fired upon them. Eventually these conflicts

developed into open warfare.

Aboriginal warriors from Lane Cove to

the Blue Mountains united to drive the invaders out, fighting a campaign of

raids, fires, robberies and assaults on farms and settlers. Their leader was

Pemulwoy, a Bediagal man from the Georges River, south of Sydney. By May 1801

Governor King had ordered that Aboriginal people near Parramatta, Georges River

and Prospect be shot on sight, had forbidden settlers from having any contact

with them and had posted a reward for Pemulwoy‘s death or capture.

Ben-nel-long, as painted when angry after Botany Bay

Colebee was wounded. Port Jackson painter 1790 or 1797. Colebee by Thomas Watling circa 1792-1797.

Bennelong was a clever and

charismatic man, who played a vital cross-cultural role in early Sydney. He

quickly mastered English and taught the settlers some of his own dialect. An

astute politician, he grew close to Governor Phillip, who, at Bennelong’s

request, built him a small brick house at Tubowgule [Bennelong Point], now the

site of the Sydney Opera House. Bennelong ate at Phillip’s table, and called the

governor beanga [father], while Phillip called him dooroow

[son]. Upon Phillip’s retirement in 1792, the two sailed together to England.

Bennelong returned after two years and resumed a semi-traditional life. He

became an Elder and was deeply mourned by his people when he died in

1813.

Colebee, a warrior of the Gadigal

clan, was about thirty five years old when kidnapped with Bennelong. He was

central to Sydney Aboriginal cultural life, involved in ceremonies and rituals

at Farm Cove and Woolloomooloo. Later, he and his wife Daringha freely visited

the settlement, often dining at Government House. In 1791, with Bennelong, he

organised a corroboree at Bennelong Point attended by Phillip and his officers.

He provided artists and botanists with information on native plants and animals,

became a friend to Surgeon John White and also acted as an interpreter along the

Hawkesbury River.

Pemulwoy:

Native of New Holland in a canoe of that country by Samuel John Neele, 1804.

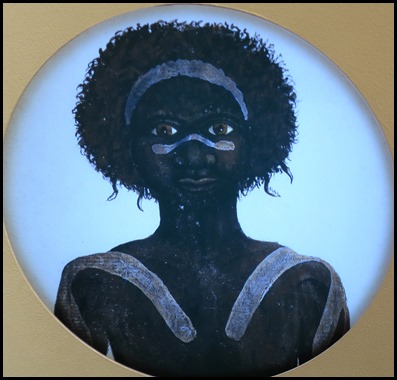

Portrait of ‘Nanbree’, Thomas Watling circa

1792-1797.

Pemulwoy was an impressive,

powerfully built warrior. He had a speck in one eye, the sign of a ‘clever man’,

and was believed to have supernatural powers. At the ‘Battle of Parramatta’ in

1797 he led one hundred painted warriors in a march down the main street of

town. This startling display terrified the settlers. At least five warriors were

killed and Pemulwoy was shot multiple times. Amazingly, he recovered and escaped

from hospital, leading many to believe him immune to gunfire. When Pemulwoy was

finally shot dead in 1802 his head was cut off and shipped to England. Governor

King conceded that though he was “a terrible pest to the colony, he was a brave

and independent character”.

Nanbaree was just eight years old in

1789 when smallpox tragically killed many of his people, the Gadigal. Found near

the harbour, covered in sores and helping his dying father, he was adopted by

the colony’s surgeon, John White. Nanbaree moved easily between cultures: he

acted as an interpreter for the colonists, but was also initiated into

Aboriginal manhood at Farm Cove. He sailed with the British naval explorer

Matthew Flinders on an expedition charting the north-east coast of Australia in

1802, but when he returned to Sydney he preferred an Aboriginal

life.

Barangaroo

was a strong-willed woman of the Cammeraigal clan. Bennelong was her

second husband, her first husband and two children having died of smallpox. A

mature woman with considerable authority, she remained firm in her desire to

maintain Aboriginal culture, and refused to wear clothing – even on her visits

to Government House. Phillip wrote that she was “very straight and exceedingly

well made”. Also described as “fierce and unsubmissive”, she was extremely angry

with Bennelong when he sailed for England, and openly her disgust for the

British practise of flogging, on one occasion threatening the flogger with a

stick. In 2007 the eastern shoreline of Darling Harbour was renamed in her

honour.

Daringha

was the wife of Colebee – sketched by Thomas Watling. The name of her two

brothers, Bone-da and Mo-roo-ber-ra, are similar to the names f Sydney beaches

Bondi and Maroubra, suggesting she had a clan connection to that area. Just

after her baby girl was born in 1790, she befriended colonist Elizabeth

Macarthur, who wrote of her “softness and gentleness of manners”. Although

described as ‘meek and feminine’, when Bone-da died participating in a ritual

payback at Rose Bay.

‘Totems’ honouring

the Aboriginal people of the area, outside the Museum of

Sydney.

ALL IN ALL PAINFUL BIRTH OF A

NEW COLONY

THINGS COULD HAVE BEEN SO

DIFFERENT |