|

Calypso

Caribbean History

The

islands of the Caribbean had a core population of descendants of African slaves,

workers and remnants of the indigenes, while colonial masters changed rapidly

bringing settlers from France, Spain and the UK, together with their

music styles. According to another version, the French brought Carnival to

Trinidad, and calypso competitions held at Carnivals grew in popularity,

especially after the abolition of slavery in 1834.

While

most authorities stress the African roots of calypso, in his 1986 book

Calypso from France to Trinidad, 800 Years of History veteran calypsonian

The Roaring Lion (Rafael de Leon) asserted that calypso also descends from the music of

the medieval French troubadours. The name was originally kaiso, which is now believed to come

from Efik ka isu 'go on!' and Ibibio kaa iso 'continue, go on', used in urging someone on or in

backing a contestant.

Over

100 years ago, calypso further evolved into a way of spreading news around

Trinidad. Politicians, journalists and public figures often

debated the content of each song, and many islanders considered these songs the

most reliable news source. Calypsonians pushed the boundaries of free speech as their lyrics spread, news of any

topic relevant to island life, including speaking out against political

corruption. Eventually British rule enforced censorship and police began to scan these songs for damaging content. Even with

this censorship, calypsos continued to push boundaries.

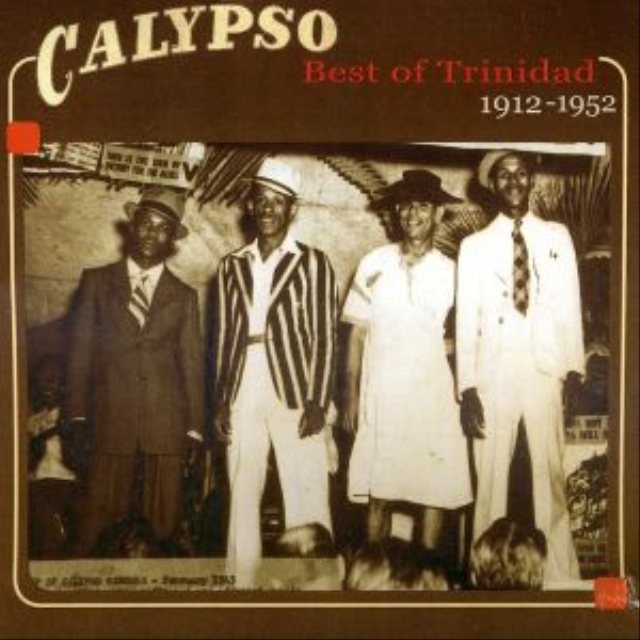

Popular music:

The first calypso recordings, made by Lovey's String Band, came in 1912 and inaugurated the

"Golden Age of Calypso". Lovey's String Band were a

Trinidadian musical group. They are known

primarily for having been the earliest known calypso group to have ever recorded.

The band did a recording session in New York City

in 1912, five years before the first jazz recordings,

and these instrumental recordings document a style of "hot" music in fashion in

the Caribbean around that time. This recording was selected for preservation in

2002 by the National Recording Preservation Board of the Library of

Congress.

By

the 1920's, calypso tents were set up at Carnival for calypsonians to practice before

competitions; these have now become showcases for new music. The first major stars of

calypso started crossing over to new audiences worldwide in the late 1930's.

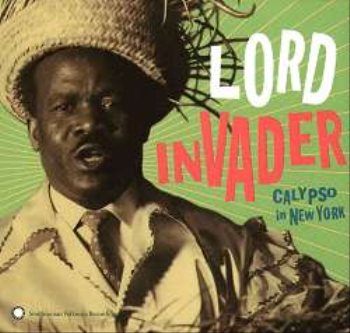

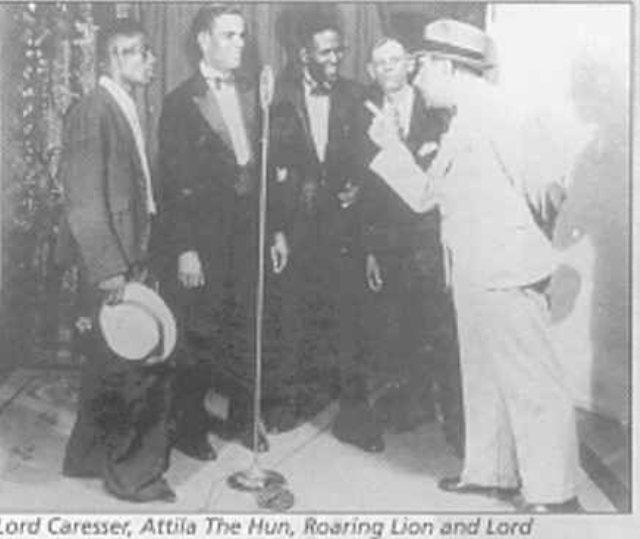

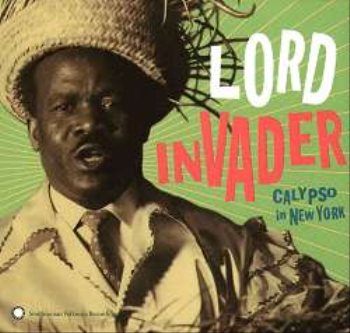

Atilla the Hun, Roaring Lion and Lord

Invader were first, followed by

Lord Kitchener, one of the longest-lasting calypso stars in history - he continued to

release hit records until his death in 2000. 1944's Rum and

Coca-Cola by the Andrews Sisters,

a cover of a Lord Invader song, became an American hit despite the song being a

very critical commentary on the explosion of prostitution, inflation and other

negative influences accompanying the American military bases in Trinidad at the

time.

Calypso, especially a toned down, commercial variant, became a worldwide

craze with the release of the "Banana Boat Song", a traditional Jamaican folk song, whose best-known rendition was done by Harry

Belafonte on his 1956 album Calypso; Calypso was the first

full-length record to sell more than a million copies. 1956 also saw the massive

international hit Jean and Dinah by Mighty Sparrow. This song too was a sly commentary as a "plan of action" for the

calypsonian on the widespread prostitution and the prostitutes' desperation

after the closing of the US naval base in Trinidad at Chaguaramas,

where we are right now.

In

the 1957, Broadway musical Jamaica, Harold Arlen and Yip

Harburg cleverly parodied "commercial" Harry Belafonte style Calypso.

Several films jumped on the Calypso craze in 1957 such as 20th Century

Fox's Island in the Sun that featured Belafonte

and the low budget films Calypso Joe, Calypso Heat

Wave

and Bop Goes Girl Calypso.

Early

forms of calypso were also influenced by jazz such as Sans Humanitae. In this

extempo melody calypsonians lyricise impromptu, commenting socially or insulting

each other, "sans humanité" or "without humanity" (which is again a reference to

French influence). Elements of calypso have

been incorporated in jazz to form calypso

jazz.

In

the mid-1970's Lord Shorty combined the

Afro-caribbean calypso with rhythmic elements of Indo-Trinidadian Chutney

music to create soca, which would grow to replace calypso as the dominant genre at

carnival.

By the time American engineers arrived in 1912 to make the island's

first records, Trinidad was a blend of African, Spanish, French and British

culture, the influences stretching back to 1498 when Columbus first arrived on

the island and named it after the Christian Holy Trinity. For almost 300 years it was a minor Spanish territory,

and remained largely undeveloped. In the late eighteenth century a colonial

tussle between Britain and France left a number of French planters homeless in

the Caribbean. Taking advantage of a Spanish law that allowed them to settle

provided they swore loyalty to Spain and Catholicism, they and their African

slaves relocated in Trinidad and Tobago. Further warfare between Britain and

France resulted in both islands being ceded to the British in 1802. By the turn

of the century, with slavery abolished in law but not always in spirit, the

island's black Creole populace had created a unique culture of its own. It now

stood ready to absorb new influences from North America and also to make its own

impact upon Western culture.

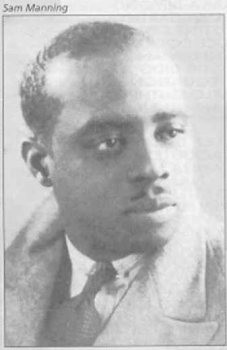

Sam Manning

The long and complex history of carnival, from which

calypso has so successfully grown, is well told by John Cowley in his excellent

new work Carnival, Canboulay & Calypso. When Victor and Columbia

first recorded Trinidadian music, in New York in 1912, they both chose Lovey's

String Band, a twelve-piece orchestra playing paseos with probably more

Venezuelan, influence than anything else. It was certainly not the calypso that

had been heard in carnival tents for a dozen years previously. A smattering on

non calypso Trinidadian music would continue to surface on record for the next

two decades, but the sound that the world would come to identify as Trinidadian

was first recorded in August 1914 when Victor visited Port of Spain:

"Among the arrivals from New York on the S.S. Matura...

were Mssrs. George H. Cheney and Charles Althouse of the recording laboratory of

the Victor Talking Machine Company, who are making a special trip to Trinidad

for the purpose of recording a complete repertoire of Trinidadian music... Mr.

Theodore Terry, the Victor Company's representative who arrived here two weeks

ago, has everything in readiness so that Mr. Cheney may begin his work at once".

(Port of Spain Gazette, 28th August 1914)

Cheney's work captured, among other things, songs by

Julian Whiterose, currently believed to be the first calypsonian on record.

Their impact upon the general public was minimal, however, and Trinidadian music

was ignored by the American record companies for another seven years. Although

Trinidad was a British : possession, American Victor and the British Gramophone

Company (HMV) had agreed, as early as 1904, how the world should be divided and

the Caribbean was clearly marked out as American

territory.

Recording started again in 1921 with

tangos, waltzes and paseos by Lovey's Mixed Band and Lionel Belasco's Orchestra,

and continued sporadically throughout the 1920s, featuring calypso artists

Johnny Walker, who vanished almost immediately, and Wilmoth Houdini, whose

career was to last well into the post-war period. In 1927 the first 'west

Indian' records were issued in Britain. They included seven couplings by Sam

Manning, and one each by Slim Henderson and Montrose's String Band. Manning was

more a generic all-round entertainer than a true calypsonian, and it wasn't

until some five years later that a solitary release on Brunswick by Wilmoth

Houdini introduced Britain to the calypso. it made little impact.

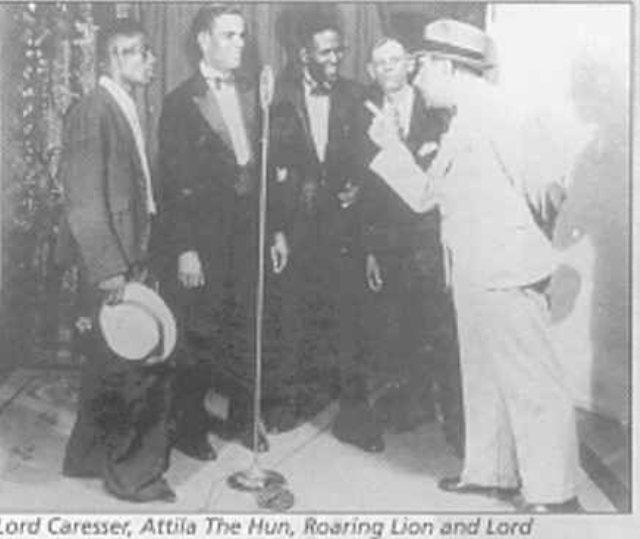

Back in

Port-of Spain, however, things were stirring, In late 1933 an expatriate

Portuguese businessman Eduard Sa Gomes founder of Sa Gomes Radio Emporiums, took

the next logical step in expanding his empire. He rounded up two local

calypsonians, Atilla The Hun and The Roaring Lion, and sent them to New York to

record for the American Record Company, owners of a string of dime-store labels.

The results were processed and pressed in America and then shipped in large

quantities by steamer to Sa Gomes. By May of the following year Sa Gomes was

advertising his "local products" available at his "two good palaces of music" in

Port-of-Spain for 48 cents each. So successful was this endeavour that later

that same year Sa Gomes sent Atilla, Lord Beginner and Growling Tiger to New

York for a lengthy recording session with the same company.

In 1935 Sa Gomes switched his allegiance

to the new and aggressive Decca label, who offered him better quality pressings

at a cheaper price, and in doing so helped to create a: catalogue of music so

successful: that is now seen as a high point in calypso history. The Decca

series included topical songs and carnival hits by popular artists like Lion,

Lord Invader, King Radio, Lord Executor and Atilla. By 1938 Sa Gomes was selling

his exclusive Decca hits at 36 cents each, or three for a dollar, only now from

his "Five Palaces of Good Music" including a branch in San Fernando and another

on Tobago. American Decca, financed by its British parent company, had good

distribution throughout North America and was giving RCA's cheap Bluebird label

a thoroughly harassing run for its money. Bluebird had launched a 'west Indian'

series in 1933 and although, in retrospect, much of what they recorded was

excellent, Decca beat them hands down in both in the Caribbean and in the New

York area where the bulk of expatriate Trinidadians had settled. Calypso also

enjoyed its first period of popularity in mainstream American culture. Bing

Crosby and Rudy Vallee were both seen associating with calypsonians, American

cover versions of Trinidadian hits were appearing on record and visiting singers

like Atilla were guesting on American radio.

In 1942 J.C. Petrillo, head of the

American Musicians Union, called for, and got, a total ban on all recording

until the record companies agreed to new terms. The resulting hiatus, which

lasted until 1945, caused a major shake up within the American record industry

and by the time recording was under way again most major companies had abandoned

'minority' markets to concentrate on the huge mainstream. This left the field

wide open for small entrepreneurs to take up the slack.

Following a

short-lived attempt by Decca to revive its market, calypso fell into the hands

of small independent companies, in much the same way as blues, country and other

ethnic musics did. Mostly New York based, labels like Guild, Manor, Stinson and

Times started recording local Trinidadians for both the American and Caribbean

markets. They had plenty of motive for doing so; writing in the Negro Digest

in 1947, Wenzell Brown noted: "duke boxes account for a large proportion of sales of

calypso records in America, for you'll find at least one of the Trinidadian

records in almost any of the 450,000 juke boxes scattered across the States".

Furthermore, Brown observed, calypsonians were appearing

regularly in Harlem's Caribbean Club, at the Vanguard in Greenwich Village and

at the Apollo on: 125th Street. Meanwhile, across the Atlantic, a parallel

situation was starting to occur. With a decimated male population and the need

to rebuild the infrastructure of the country, the post-war government in Britain

advertised widely in both Trinidad and Jamaica for people to come "to the mother

country". Good wages were promised, although, according to more than one

account, relative costs of living were often glossed over. Thus from 1948, and

in increasing numbers for several years thereafter, ships packed with hopeful

immigrants arrived at Tilbury, Southampton and Liverpool. The result was the

blossoming of a fresh and substantial culture within Britain.

In January

1950 an English jazz promoter and radio personality, Dennis Preston, organised

the first English recordings of West indian music since Sam Manning's 1927

session. Backed by an authentic band that he had constructed by scouring the

country, Preston recorded Lord Beginner and Lord Kitchener for Parlophone

records, one of EMI's labels. He went on to produce calypsos regularly for the

independent Melodisc label, an interesting operation that issued specialist

music as diverse as Brownie McGhee and Cantor Joseph Cussovetsky. Other labels

such as Kay, London, Lyragon and Savoy followed suit and until the early 1960's

were supporting a small but loyal local market.

British based

calypsonians commented on events within their new environment, especially

cricket, politics and royalty, and throughout the '50s and early '60s a

perception of calypso entered British mainstream consciousness. At its tackier

end it included daft interpretations by the likes of Harry Belafonte but it also

meant that a strain of topicality and satire was constantly available. Lords

Beginner, Kitchener and Melody, and Roaring Lion all commented on aspects of

British society throughout this period.

Calypso's fate in Britain was sealed; as

much as anything, by the generation gap. By the mid 1960s most young

Trinidadians, especially those born in Britain, found little to relate to in

either the lyrical content or the rhythm. At the same time, Jamaican music and

culture was undergoing a similar metamorphosis.

The reasons why Victor or

Columbia never visited Jamaica to record are unprovable. Perhaps the companies

had no faith in sales potential; perhaps plans were cancelled following

disappointing sales from the initial Trinidadian recordings. Whatever the

reasons, no major company went to Jamaica, and as a result we have no aural

reference for anything much before 1950. Jamaica's recolonised indigenous music

was mento, a guitar-accompanied atrophic song deeply influenced by calypso. The

earliest recorded examples currently known date from the late 1940s, a time when

the new generation in Jamaica was rejecting the genre as old fashioned and

looking for something fresh.

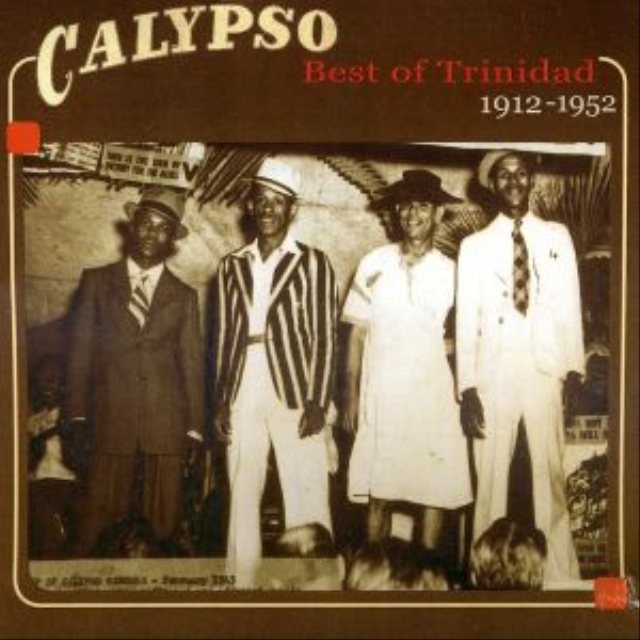

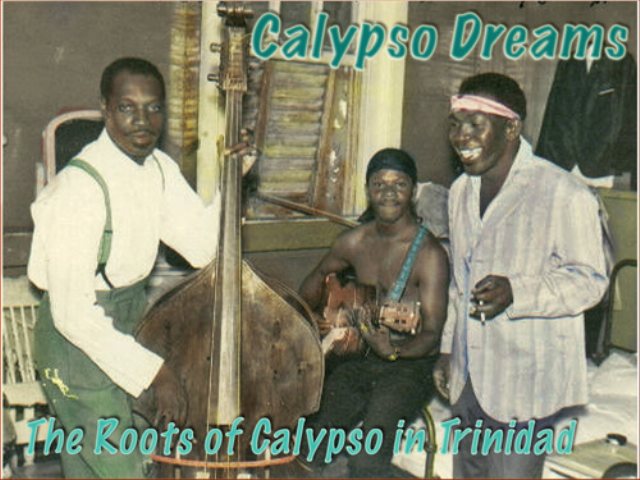

Lord Invader The Growler. Attila The Hun (dressed as Eve) and

Roaring Lion, 1943

What they found

and liked came from outside the island, and it came first by radio, By the late

1940s radios had become commonplace in Jamaica, largely due to the presence of

the British Rediffusion Company, who rented three waveband bakelite table models

for a few shillings a month. By attaching large aerials to these sturdy

receivers, people could pull in signals from all around the Caribbean including

Cuba, Mexico and Venezuela. The ones that grabbed their attention, however, were

those coming from the American gulf coast cities; Corpus Christi, Houston,

Mobile and New Orleans. The music on offer was a diverse selection: hillbilly,

Latin, jazz, pop and rhythm & blues, but it was the new, energetic R&B

that most young Jamaicans responded to. Black American music was undergoing some

fundamental changes in style, approach and instrumentation; it was fresh,

vigorous, exciting and often loud. It was no longer being controlled by major

record companies, as it had been in the pre-war era. The new, independent labels

were much more in touch with their customers' needs. The emergence of black

radio stations and the continuing spread of the juke box helped to quickly sew

together the fabric of the new music by disseminating it more widely.

In

Jamaica people responded quickly and enthusiastically, and the sound of Fats

Domino, Joe Turner, Wynonie Harris and Roy Brown became an integral part of

Jamaican society. Not content with listening to far-off radio signals, a few

enterprising people made trips to North America to buy records. They came back

with arms full of discs by newly recorded and often obscure artists and played

them at neighbourhood yard parties. From these simple beginnings grew the first

mobile sound systems that would soon dominate Jamaica's musical culture.

Principal among the characters involved were Duke Reid and Coxsone

Dodd.

Lord Caresser, Attila The Hun, Roaring Lion and Lord Executor with

Eduardo Sa Gomes, 1936

Percy Miller,

who as a young man in Kingston had observed events at first hand, remembers:

"Daddy Nick (an early DJ) started to import records from Randy's Record Shop in

Tennessee because he didn't have any other way of getting the records. So it

developed, there were sound systems that might carry a thousand records each on

lorries and they would have competitions between them. During the competitions,

those records that the guy got from the States, you couldn't see the names on

the labels because they were scratched out, but we would try to listen to the

voice. Smiley Lewis, you would recognise the voice, or perhaps the sax or

guitar, and then the audience would have a competition among ourselves to

identify the new records."

The sound systems were huge affairs,

transported from one location to another on Trojan lorries (hence the name of

the early Jamaican record label), run by generators and operated by up to a

dozen 'helpers'- strong young volunteers - who set up the equipment and guarded

the all important records from any possibility of industrial espionage.

"The first system I listened to was Coxsone but at that

time Reid was on top with his records and fans. His amplification was thousands

of watts but of course at that time we didn't realise that as they were playing

in the open air, right off the trucks, but if you stood too close to the

speakers your stomach would move to the power of the music. They had to strap

down the speakers with ropes to stop them from jumping around. Each sound system

would have its own fans who travelled with them and each system would try to

improve its records; Duke and Coxsone were the only two guys who could go to the

States to buy records - they were the only two with enough money! Coxsone and

Duke never played together but they would play in the fields next to each other

and they'd try to out-do each other with records. The most popular records were

by Fats Domino, Smiley Lewis, Joe Turner and Shirley & Lee, however, if a

sound system got a record by, say, Lester Williams, it would draw a crowd from

other systems just to hear that new record."

The rivalry between

Coxsone, Reid and other minor DJs like Daddy Nick and Blue Miller resulted in an

almost paranoid secrecy; the DJs would deface the record labels, routinely

announce them by titles of their own choosing and almost always omit to announce

the artist. Thus, King Perry's California Blues would become Downbeat

Shuffle, while Shirley & Lee's Let The Good Times Roll was known

as Come On Baby.

Stanley Motta,

a Kingston-based businessman, set up the first recording studio and pressing

facility on the island around 1956. He produced a variety of 78rpm records to

order and is believed to have been responsible for a number of

'unofficial' Jamaican labels issuing American R&B. Again, Percy Miller takes

up the story: "Coxsone went back and forth to the States, he would pick out, for

instance, four popular records and have Motta press up 10,000 copies. Every

street corner you'd find someone with an amplifier selling these records he'd

pressed. But he couldn't always find the things he wanted, so he decided to do

something for himself. He made a record called Pink Lane Shuffle, and

then Reid heard it and went and made Luke Lane Shuffle."

Coxsone had issued Pink Lane

Shuffle on his new, eponymous label and continued with other locally

recorded instrumentals including the hit Milk Lane Hop by Clue J &

His Blues Blasters, a pick- up group that included Don Drummond and Ernest

Ranglin, and went on to become known as the Skatalites. It was from this group,

says Percy Miller, that the Ska sound took its name. ::

"in about 1959 the sound systems were badly hit by a guy

called Edwards who went to the States and brought back thousands of records and

started selling them in Jamaica. These were records that Coxsone and Reid were

playing on the systems, and for the first time people could freely buy the

records and the systems no longer had exclusives This guy, his people had money

and he had brothers in the States, regularly shipping him stuff. On top of this

he had a more powerful amplifier. So, Coxsone and Reid started to play the

records they had made themselves, and they found they were really popular and

came to rely on them more and more." Thus it was that locally produced records, like Lord

Lebby's wonderfully energetic reading of Louis Jordan's: Caldonia or

Laurel Aitkens Aitkens Boogie, allowed a style to evolve that was

becoming essentially Jamaican rather than just a copy of the American sound.

R&B became Ska, Ska became Blue Beat and Blue Beat eventually became Reggae.

While these events had been occurring in and around Kingston, Jamaican

immigrants in England, bringing with them a taste for R&B, found their needs

ill served. Vogue: records issued a few 45's by Shiriey

& Lee, Amos Milburn and others, and a trickle of R&B appeared on the

London label. There was some material to be had by trawling through the jazz

catalogues but it was a hit and miss affair.

To a degree the gap was filled by a small,

obscure record shop in North West London. Tucked behind the Kilburn &

Brondesbury tube station was a place run by an ex-dance band musician and

jazz enthusiast called Ralph Foxley. In about 1953, responding to numerous

local requests, Foxley privately pressed 25 copies of an Amos Milburn record

that he happened to have. It sold out in one morning. Realising the potential,

he contacted a friend who worked on the passenger liners sailing from

Southampton and arranged to have him buy a regular selection of new R&B

records in New York. These would then be copied and pressed on metal acetate

singles, which Foxley sold across the counter. News quickly spread and Saturdays

at Foxley's became famous. An affable man, Foxley presided over what became, to

all intents and purposes, a regularly scheduled party. People came from all over

London and as far afield as Birmingham, Bristol, Liverpool and Manchester.

Friends would meet, talk, listen and buy - the session finished only when the

last record had been sold - it served as a meeting place for musicians and fans

alike at a time when there was little else to be had.

By the early 1960's

Jamaican music was more readily available in England. In 1961 the Blue Beat

label, distributed by Melodisc, was regularly issuing new 45's and two years

later Chris Blackwell would launch Island records - just in time to happily

collide with an explosion of interest in American R&B among the white youth

of Britain - the rest, as we all know, is rock history, but the world-wide

influence that Caribbean music has today is underpinned by these

events.

ALL IN ALL A

VIBRANT STYLE FULL OF

RHYTHM

|